Oscar-Winning Actress Marlee Matlin: The Transcript

Read a full transcript of Episode 38 of Slate Represent.

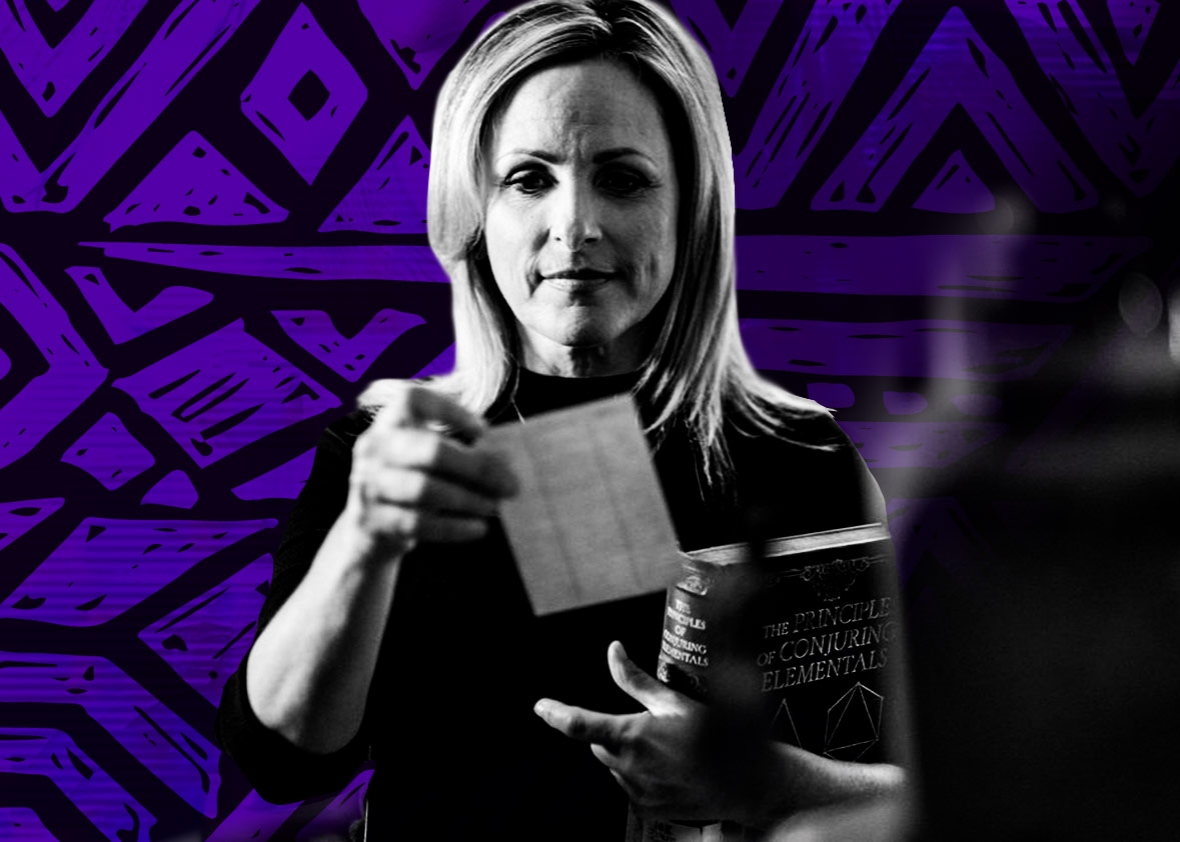

Photo illustration by Slate. Photo by Eike Schroter/Syfy.

This is a lightly edited transcript of Episode 38 of Slate Represent, in which host Aisha Harris interviews actress and advocate Marlee Matlin about her recent guest spot on The Magicians, her 30+ years in Hollywood, and her advocacy for deaf and disability representation on screen.

Also, Slate web designer Derreck Johnson shares his “Pre-Woke Watching” story about noticing colorism in movies like House Party and Coming to America.

Represent Ep. 38:

[Scene from Switched at Birth]

Melody: This is a deaf school where we can be seen, but the world doesn’t recognize us.

Kathryn: That’s not true of all hearing people. I recognize you.

Melody: That’s nice. But I’m here because I’m a parent.

Aisha Harris: Hey, this is Represent and I’m Aisha Harris. Welcome back. That clip you just heard is a scene from the family drama Switched at Birth, featuring Marlee Matlin as Melody, who is communicating via sign language with Lea Thompson as Kathryn. That’s Thompson’s voice you’re hearing.

A bit later in the show, Marlee joins us via her longtime interpreter Jack Jason to discuss her incredible career. For those of you who are listening in and want to share this episode with someone in your life who is deaf or hard of hearing, we’ve also prepared a full transcription that will be available on the Slate.com site the same day this episode drops in your feed.* And we’ll put a link to it in our show page. Unfortunately, this isn’t something we do with every episode and we really regret this fact, though I will say the reason why is because we just currently don’t have enough resources to make that happen every single week for all of our podcasts across the Slate and Panoply network. Hopefully that won’t always be the case.

Now, before we jump into my Marlee interview, though, how about we do a bit of Pre-Woke Watching? A little while back, one of Slate’s wonderful members of the art team, Derreck Johnson, sat down with myself and Veralyn to discuss a movie he’s always loved but knows has its issues. So here we go again: royally complicating one of your longtime faves.

* * *

AH: So yes, Derreck, we are here today and you need to tell me what your Pre-Woke Watching experience is.

Derreck Johnson: OK, so, one of my favorite comedies of all time—pretty much everybody’s for the most part, I think—is Coming to America. Right?

[Scene from Coming to America]

[Sound: Typing on keyboard.]

Akeem: Hello.

Lisa: Hi.

[Sound: Typing on keyboard.]

Akeem: I am Akeem.

Lisa: It’s nice to meet you, Akeem.

Akeem: I have recently been placed in charge of garbage. Do you have any that requires disposal?

Lisa: No, it’s totally empty.

Akeem: Well, when it fills up, don’t be afraid to call me. I’ll come take it out most urgently. When you think of garbage, think of Akeem.

DJ: Coming to America is a hilarious movie. It’s classic, it still holds up. And there’s something I didn’t notice until—I was young when it came out, and all you knew is it was a really funny movie. It wasn’t until I got old that I started to realize the dichotomy between two biological sisters in the movie, Lisa McDowell and Patrice McDowell. Lisa is the light-skinned one—fair-skinned, kinda light-skinned—and Patrice is dark-skinned. The fair-skinned sister has great hair, beautiful hair. She’s very beautiful, picturesque. She’s business-minded, she has a great job, she has a good head on her shoulders. And her younger sister, the dark-skinned one, she’s portrayed as—how should I put it?—she’s kinda fast! [Laughs] She hits on Akeem and Semmi, and at the end of the movie, she takes Mr. Soul Glo away.

AH: [Laughs] Soul Glo! Yeah, so we’re seeing some colorism going on here.

DJ: Yes there is, yes there is.

AH: I don’t know: Do we need to explain what colorism is? I think you kind of just did.

DJ: I did, but do you want to go ahead and give them the—[laughs]

AH: I mean, essentially, within not just the black community—it can be within the Latino communities and other communities as well, and Asian communities—is the idea that darker-skinned women, especially, are a certain type. Often the less-desirable type, the more “ghetto,” the more slutty or fast and loose—more unattractive—whereas fairer-skinned, the closer you are to looking white, the more attractive you are, the more refined you might be in your characteristics. Yeah, so that’s a thing that happens. It also happens in so many different movies and casting, when you think of someone like Lena Horne, who—Lena Horne was amazing, but she also was subject to that sort of casting, of, like, she was the light-skinned one, so when you put her up against someone like Ethel Waters in Cabin in the Sky—who is a heavier-set woman and also darker-skinned—they played that out. One was the attractive one, the other one was the matronly, homely one. So we have that going on 40 years later, after Cabin in the Sky, in Coming to America.

DJ: Yes. I don’t want to ruin it for anybody. It’s still a great movie, it’s still a hilarious movie. But it’s just something you notice. I also mentioned, too—this also happens in House Party, too, another one of my favorite movies.

AH: Oh, you’re right.

DJ: With the two female leads. It’s A.J. Johnson who plays Sharane and Tisha Campbell who plays Sidney. Sidney is the light-skinned one, and Sharane is the dark-skinned one—Sharane lives in the projects; she’s more experienced, per se, with guys. Tisha Campbell’s character is portrayed more as kind of a nicer girl. It happens there too. I’m not sure if it’s intentional or what, but it happens in there too.

AH: When did you realize? Like, when did it dawn on you with Coming to America and with House Party?

DJ: I noticed this when I got older—I don’t know, in my mid-20s or so? I was watching, and I saw the parallels between the movies and was like, This is a little crazy.

AH: When you realized this in your 20s, was this also when you were coming to terms with realizing that colorism existed outside of that movie? Or had you known for a while—like, oh yeah, there are these stereotypes about the way people perceive light skin versus dark skin.

DJ: I think it’s a little bit of both. I can’t exactly pinpoint when I started noticing this thing, but I kind of got more conscious of that kind of thing, of race relations like that. I can’t really pinpoint it. I just happened to realize it one day. I don’t know; I just got woke one day. I guess? [Laughs]

AH: [Laughs] You just woke up one day! Woke. [Laughs]

DJ: I think talking to my friends too. Friends bring up certain things, too. I’m like, Oh, yeah, I think you’re right.

AH: So it sounds like you still love both of those movies, though.

DJ: I do.

AH: So you can look past it.

DJ: Yes.

AH: Yes. OK, that’s fair.

DJ: I totally can. I mean, I still notice it every time I watch the movies, but for some reason, it’s not crazy where I don’t like the movie anymore. I don’t know. There are actually more important movies in black film, so I think—

AH: Well you’re actually the first person I’ve talked to so far for Pre-Woke who has a child—actually has a child. You have a very adorable daughter.

DJ: Thank you.

AH: I assume this is a movie that you might want to have her watch at some point. Would you talk to her about this issue and explain it to her when you introduce it to her, or do you think that’s something she’ll have to come to on her own?

DJ: I’m not going to—probably won’t explain it to her right away. Maybe she’ll figure it out. Actually, my daughter is very light-skinned too. My daughter right now has light skin and blue eyes, which is really crazy. I think she will deal with this kind of thing once she gets older. Crazy enough, I was in the supermarket the other day—I was kind of just pushing her around—and a lady came up to me. Usually, a lady comes up to me and goes, “Oh, your baby is so beautiful.” I’d say thank you. And usually they ask next, “Is it a boy or a girl?” Which is OK. Or how old she is. The first thing she said is “Is your wife white?”

AH: Was this a black woman?

DJ: I don’t even know what her nationality was, I can’t even—

AH: But she was like, ethnically ambiguous.

DJ: Right, right.

AH: And she asked you that.

DJ: Right, and I was like No, my wife’s latin. It was all OK. I’m like, “OK, have a good day” [laughs] when I walked away from her.

AH: Who asks—what? [Laughs]

DJ: It’s crazy. I think there’s still an issue of people that don’t realize that we can come in so many different colors and different shades. I swear, this happened.

Producer Veralyn Williams: I want to know, what it was like? Hi. Hi. Baby’s so cute. What—how did you get there?

DJ: That’s how it happened. There’s no “get there.” [Laughs] That’s how it happened.

AH: Well, you know what? Some people just have no filter.

VW: This is Veralyn that’s been screaming off-mic for a second. Did she at least acknowledge that what she was asking you was inappropriate?

DJ: That’s the thing. I don’t think she even realized what she said sounded inappropriate. Maybe, I don’t know. But that’s the first time that ever happened. And I feel like, you know what’s funny? This comes back around full circle. I’m sure my daughter, when she gets older, is going to have to deal with all kinds of issues with complexion and whatnot, trying to describe what she is and what she identifies as. I got my first little taste of it that day at the supermarket.

AH: Wow.

DJ: This was in Williamsburg, by the way. [Laughs]

AH: Of course. Williamsburg, Brooklyn. Yes. [Laughs]

VW: Around the issue of colorism, I kind of also—Martin? Gina and—

AH: Yes, Gina and Pam. Actually, I interviewed Tichina Arnold last summer, and I actually asked her about this.

[Excerpt from Aisha’s interview with Tichina Arnold]

Tichina Arnold: I would say no to your question only because what Martin and I had was really organic. So wherever that comes from is because of us personally, and not because of what we really saw in each other. It just so happens that Tisha is very light. And what happens is, girls would come and watch the show in the studio audience, and every time Tisha would talk, they would suck their teeth. “Ugh!” They didn’t want her to have the man, they wanted me to have the man. It’s like: You still get it on both ends. Light-skinned women still get the same treatment. We’re treated differently, but you still have to go through hurdles.

Aisha Harris: You’re still black.

TA: Either you’re too black, not black enough. It’s always something.

AH: And then of course—I mean it’s kind of different, but the fact that on Fresh Prince there was the original mom [laughs] and then the second mom got lighter. It was like, Oh, OK.

DJ: [Laughs] Right, right.

AH: Alright, sure, that’s what’s happening!

DJ: No warning. Just boom, here ya go.

AH: Anyway, I’m so glad we talked about this. And obviously, I’m sure people, maybe they’re yelling, listening right now—there are lots of other issues with Coming to America that we could go into, but we’re not going to. We’ll maybe save that for another Pre-Woke experience. I also love the movie—I think it’s very funny—but we’ve gotta admit, there’s a lot. If they were to make it today, it would not fly.

DJ: No, not at all. Not at all.

AH: So we know, there are other things we could talk about, but we focused on the colorism today. Maybe another day, we will be more woke about other parts. Veralyn is just scrunching her face and nodding in agreement right now. [Laughs] Thank you so much, Derreck, for coming on.

DJ: No problem, no problem.

AH: And sharing your Pre-Woke. Good luck with everyone asking you about your white wife! [Laughs]

DJ: Nice shout to Vanessa.

AH: Yes! [Laughs] Shoutout to Vanessa.

DJ: She loves that story, yeah. [Laughs]

AH: Thanks Derreck.

DJ: Thanks.

* * *

AH: As we all know, these last few years have seen conversations around representation onscreen really heating up when it comes to race, gender, and sexuality. Where there hasn’t been as much attention paid is to the issues around disability, and I know I’ve been guilty of not really considering it as much as I probably should. Recently, I got a chance, though, to have a conversation with Marlee Matlin, who is not only an award-winning actress—she has an Oscar—but a prominent activist for disability representation. So here’s my conversation with Marlee, which was conducted via her longtime interpreter, Jack Jason.

* * *

AH: So, Marlee, you recently did a guest spot on Season 2 of The Magicians. You played Harriet, a magician whose BuzzFeed-like website is also a site for encoded magic. I thought it was really great the way in which you were first introduced on the show, in which you greet two of the characters in sign language, and one of them sort of freaks out and believes you’re casting a spell upon them. I thought that was just really clever and funny. I’m curious as to how you landed the part on that show and what made you want to do it.

Marlee Matlin (via Jack Jason): Well actually, it started, honestly—I’m not one who watches sci-fi. It’s not just part of the type of shows that I watch. I don’t know if my kids watch it either, but I have heard a lot about The Magicians and that it was getting a lot of great reviews, because I just keep up on things in the business, and The Magicians kept popping up in my Viewfinder, if you want to call it that. I thought it would be a no-brainer to have a deaf person on the show because there is a lot of mystery, magic—from a person who is deaf, you would imagine there wouldn’t be any barriers. My character, who’s Harriet, would be somebody that could fit in quite well. The two visitors to FuzzBeed start signing the character Arjun.

[Scene from The Magicians]

Penny: We’re here for the book. Principles of Conjuring Elementals—that’s 10 years overdue. [Beat] Whoa, whoa, whoa!

Kady: She’s not casting. She’s signing.

Penny: Oh. I don’t speak that.

Kady, interpreting for Harriet: She said we don’t look like librarians.

Penny: Alright, well tell her we’re looking for the book.

MM: Actually, when we did it in the first take, he scared the hell out of—when he jumped and I realized, Oh, OK, this is what they’re doing. They are playing a joke—they’re going to play with signs and finger-tutting. It really worked out quite well because of the fact that there’s so much diversity in this show. There’s so much mystery in this show. There’s so much humor, and we can play with people’s perceptions of what a deaf person can and can’t do on the show. A lot of people responded very positively to it, and they saw that it worked. I was very pleased. So it’s the perfect vehicle and the perfect show for me to be on.

AH: Yeah. And you are also currently on Switched at Birth, which is wrapping up its fifth and final season right now.

MM: Two more episodes left, the final of the 103 episodes. And then we close the chapter on that show. But it will live forever in Netflix.

AH: Yes, yes. It is on Netflix right now; that’s actually how I got to catch up with it. You’ve been on it since the beginning, and you play the mother of Daphne. Daphne is one of the characters—

MM: No, I don’t play the mother of Daphne. I play the mother of Emmett.

AH: Yes, the mother of Daphne’s best friend Emmett. And just so those who are listening and are reading know, Daphne is one of two daughters who have been, like the title says, switched at birth.

[Scene from Switched at Birth]

A: The hospital believes there was a mix-up.

B: Did they actually use that word? “Mix-up”?

A: Someone wasn’t careful matching the ID anklets. It’s extremely rare, but it happens. You took home someone else’s baby, and another family took home yours.

AH: The whole show is about the family dynamics.

MM: Yeah. Daphne is the deaf one, and Bay is not the deaf one.

AH: Right. And so Daphne and Emmett and your character, Melody, are all deaf on the show. I’m curious as to like, after all of these years, how much are you going to miss this show, and what was the dynamic like on set for you while you were doing the show?

MM: I’m going to miss going to work there because I really enjoyed the camaraderie on set. The cast and the crew. The writers. They made a concerted effort to include deaf characters, and this is the first network show that had both deaf and hearing actors together, working in conjunction to tell stories. The use of American Sign Language was prominent on the show; it was in each and every episode. They were very innovative, they used subtitles, they educated, they entertained. People were always fascinated with the use of sign language. So many things you could learn from the show—you could look at it from so many different angles: the fact that it won awards, the fact that it reflected real-life events. It really encompassed everything; there were no barriers on the show to watching. Anybody could watch it. We had an episode, and I think it was a learning experience for most people—people who weren’t accustomed to watching a show with no sound.

AH: Yes.

MM: But we did an entire episode in American Sign Language. And that was awesome. I’m going to miss the people on the show, I’m going to miss my character. I felt free to play her because I wasn’t restricted in any way in terms of having to learn how to speak lines. I got my character—she made sense to me. She was authentic and the writing was authentic. Not only was I a mother for Emmett, Daphne’s friend; I was also a guidance counselor at a school, a mainstream school. She took care of things in a way that was familiar to me. The storylines that they tackled on the show, whether they were talking about racism or they were talking about—Lizzie Weiss really was not afraid to go ahead and tackle touchy subjects. It’s very rare these days. I hope that other people will pick up the mantle and continue this, because it makes sense to create more roles for deaf actors out there.

AH: Right. One of the things that really struck me was the way in which the signing on the show went as fast as you would expect people in real life to speak.

MM: It’s just like another language. That’s all it is. I just think it’s prettier: It’s artistic-looking, it’s prettier, it’s very expressive. Not only are you talking about moving your hands, you’re moving your face, you’re moving your body. I’m not saying that other languages aren’t pretty—they’re lovely to listen to—but I think sign language is perfect for the visual medium. It’s visual: You can see it. And a lot of people are motivated as a result to learn the language.

AH: Yeah, that was going to be one of my questions: How did hearing viewers respond to this in Season 1, as opposed to as the show went on—have you found that they’ve been more receptive?

MM: I think at first people were fascinated by the show, because knowing again—we’re talking about younger audiences. Younger audiences are looking for something to relate, they’re looking for something different, they’re trying to find parallels in their lives on these shows and reflections of what happens. In this show, when you add the layer of sign language onto it, there’s this idea of Oh, wait a minute, there are certain people that we think different about. There is isolation, there is a separate community—and there’s some kind of identification there. It’s learning a language but then not learning a language—being part of a community but not being part of a community. There’s definitely a lot of things that happen in the deaf community that they could see reflected in their own lives. It was immediately received very well; I think it might have taken a couple of episodes because it’s not necessarily something you see everyday, sign language all the time. But it went rather quickly and, as a result, classes boomed in sign language and of course, it helped that we had some beautiful people on the show who were great-looking actors.

AH: [laughs] Indeed.

MM, directly: Not me!

MM: Not me, though. I don’t know if I’m necessarily the one.

MM, directly: I’m the old hag.

MM: I’m the old hag on the show.

AH: Oh, I would beg to differ on that! But yes. [Laughs] There have been criticisms from some within the deaf community about the fact that Katie Leclerc, who plays Daphne, she in real life experiences only intermittent hearing loss—

MM: She says she has a hearing loss, so who are we to judge what she has? She has Ménière’s disease. That causes a deafness, and I have seen it happen with her where she loses her hearing right on the spot. It’s fascinating to see, and scary, but she knows how to take care of herself. And yes, she hears, and yes, she speaks, just like a hearing person. But that doesn’t bother me at all, because she was cast in the show. She knew sign language, she knows what it’s like to be deaf when her Ménière’s disease comes up. And so she’s not faking it whatsoever. It’s just that there’s a degree—you can’t judge who that person is. If a hearing actor is playing a deaf actor, that’s a different story. But she’s not hearing. She has a hearing loss. She knows what it’s like to be deaf. And she plays her character as a result of those experiences that she’s had.

AH: Yeah.

MM: She’s able to do that.

AH: There’s also been, just beyond that, sort of, criticism, there’s also the fact that she has—and she’s been open about it—about the fact that she has a—she calls it a deaf accent, a quote, unquote deaf accent. I mean, what are your thoughts on that, in terms of the way?

MM: Well, I can’t—I—This is the answer I can give you: I can’t hear it.

AH: Well, yes. [laughs]

MM: So I’m not the person you should ask to judge about it. I can’t hear it, I can’t know it, I don’t know what to say about it.

AH: Yeah. Like you said, with Katie, totally fine. But in terms of non-deaf actors playing deaf characters, that’s a whole other story for you.

MM: Mm, that’s a problem.

AH: Yeah.

MM: Because there are so many talented deaf actors out there that haven’t been seen. And there are just a few. I know how this goes. I, myself, was an unknown actor. And they struggled with casting me in Children of a Lesser God. It is a problem for hearing people to play deaf people because it’s A, not authentic, and B, there are actors who could do the job well. So, there are people who are both brilliant and artistic who can do exactly what the role requires for them if the role fits them, if they look right for the role, if they’re appropriate for the role. So I don’t know why we have to continue this. Why we need to have this deaf version of blackface. There are so many opportunities for deaf actors. It’s just not right.

AH: I mean, a part of it also seems to be the fact that there aren’t just as many roles being created for deaf people.

MM: Yes, there’s not enough roles, and when they do come out—listen, I’m not going to accuse every person or deny every person the opportunity to play a role as an actor. And perhaps writers—I’m not going to accuse writers for not doing enough for deaf people, because maybe they don’t have the opportunities to meet deaf people, they don’t know anything about sign language. It takes just a moment to learn, but I can’t blame them if they’ve never had that encounter. But if you’re going to write a role about a drug addict, you need to know what it’s like to be a drug addict, and you need to research it, and you meet with people. The same thing goes for deaf people. If you want to write a role for a deaf person, then you need to research, you need to do your homework. But it can also be that it doesn’t have to be about being deaf. You can put deaf people in any role—it’s not rocket science.

AH: Mhm. Right, it’s just like your role in The Magicians. Like, that character didn’t necessarily have to be portrayed by a deaf person. But it was. Yeah.

MM: Right. Just happens to be played by an Oscar-winner deaf person.

AH: Well yes—

MM: And it makes it more interesting! And not because of the Oscar, let me say that.

[laughter]

MM: But it’s just more interesting to put a deaf person in a role, a person who happens to be deaf, just adds—it adds diversity.

AH: Exactly.

MM: It adds diversity, and that’s what we’re talking about these days. So why not?

AH: Well, I want to get to your Oscar-winning role in Children of a Lesser God, because that was your film debut, in fact. And I’m curious as to just first how you got your acting bug and what it was like for you to navigate the industry at that time, around the time that you were in Children of a Lesser God, because that was an—even more so than it is now, because there weren’t that many opportunities for people with disabilities to be seen on screen.

MM: Well, OK, so, let’s tackle this from two different perspectives. Yes, it was a big thing that they hired a deaf person to play a deaf role. Initially, they were going to cast a hearing actor in that role, but Mark Medoff had specified in the notes for his play, and probably had the same clout for his film, that the role had to be played by a deaf person. And I think it took somewhere between two and four years for them to cast the role. They were looking all over. I was in a stage production of Children of a Lesser God, coincidentally, in Chicago—that’s where I’m from—and the director, Randa Haines, saw me because they sent a casting agent to all these productions and filmed the cast, so I did my thing as part of this casting process, and I was in the play, and auditioning. I was in a supporting role, I wasn’t even in the lead. And I was 19 years old and suddenly, the next thing I know, I’m going out to audition for the film, I’d just got out of community college, I’d been acting since I was, what, seven or eight years old—I was with the International Center on Deafness in the Arts outside of Chicago—yes, since I was eight. And I’d done stage plays and musicals in sign language. And I basically thought of myself as a ham. Anyway, so, what happened was they saw me on this video. They bring me to audition. They bring me to the final tryouts. And I get the film. And what happens is I’m the first person to get an Oscar—now remember, at this time there was no social media, and it was hard to get the word out. Now, with social media, everybody knows. There’s no excuse for not putting a deaf actor in a deaf role. But back then, it was completely different, trying to find the right actor. How are we going to find a deaf actor? Casting for two to four years. But because of what we’re doing these days with social media—this is what I struggle with, there’s no excuse for not hiring deaf actors for deaf roles. It just doesn’t happen. Even Rex Reed said when I won the Oscar, it was the result of a pity vote, and I didn’t deserve the Oscar because I was a deaf person in a deaf role, so how is that acting? He didn’t understand that deaf people could be actors. That you somehow had to play deaf. That you play a person in a wheelchair. That you have to play blind. And that kind of perspective has to stop. Because there are plenty of actors who are deaf. There are plenty of actors in wheelchairs. There are plenty of actors who have visual barriers. There are all sorts of people with disabilities who are actors and don’t have to be necessarily in roles that are about being disabled. You can just put a disabled person in the role. Twenty percent of our population has a disability, and it is not reflected in film or television. Only five percent of roles in TV are played with characters that have disability, and of that five percent, only five percent are played by people who actually have a disability. So 95 percent of people who play roles with disabilities are not disabled.

AH: Right.

MM: That’s a big bowl of wrong.

AH: Yeah.

MM, directly: Wrong, wrong, wrong.

AH: Yeah. I mean, you had someone like Rex Reed saying that. Did you find support elsewhere during that time period?

MM: I did, I mean, I found support. When I won the Academy Award, I got a huge—I mean, there was a huge groundswell of support for the deaf community from deaf people who spoke, deaf people who signed, deaf people who did both. And they were very very proud of me, and at the same time, they gave me a great deal of responsibility. And that responsibility showed up at the following year, because the following year, I wanted to show people in Hollywood that I had another side of me, and that side of me was that I could also speak. That was something I’d always been able to do. So when I spoke at the Oscars—and I’m not talking about all deaf people—but when I spoke at the Oscars, a good amount of people felt that by speaking, I was trying to send a message to parents of deaf kids that they should speak and not sign.

AH: And can you—

MM: So now—

AH: Sorry, and can you just explain what you mean by speaking in terms of—I watched the clip, actually, and I know there was an interpreter—was it you, Jack, actually who was the interpreter?

Jack Jason: Yes, it was me.

AH: Yes.

JJ: I’m stepping out of my role for a second and say yes, it was Jack, Marlee’s interpreter, for that. Yes. Now I’ll go back and interpret for Marlee.

AH: Yes, so that’s what you mean when you say speaking in terms of having an interpreter as well in that case?

MM: I spoke and signed at the same—first I signed the introduction for the Oscars. Then I spoke the name of the nominees that I worked very hard for for several weeks with the potential names, because I wanted Hollywood to see I could also speak, because the character I played in Children of a Lesser God only signed, and that wasn’t exactly who I was, and it’s nice to know who I am as a person, that I can sign, I can speak, I can do both, and also opens me up to roles where they might need a deaf person who speaks. That was my intention. That was my intention. However, some people in the deaf community misunderstood my intention and thought I was sending a message out there that speaking is the preferred mode of communication for people who are deaf, as opposed to signing. And that somehow you should pass this message along to your children. And that was the last thing that was on my mind. I didn’t even know that there was this controversy between people who signed and people who spoke because I was young, I wasn’t politically motivated, I had never been in that argument, I had never known there was oralism versus sign language. That wasn’t my thing. I was just, as I said, a down-to-earth person from Chicago. So that was my defense at the time. And people misunderstood and chose to use me as their—I mean, I use Jack now. If I spoke now, you probably wouldn’t understand me. Maybe five percent of your audience might understand. Because sign language is the preferred mode of communication for me in this type of setting. But in other settings, I can speak.

MM, directly: I can speak. You hear me speak.

MM: And if I go to the grocery store or if I—I mean, I don’t need an interpreter all the time with me. It just depends. But I wanted Hollywood to see this part of me and to know who I was. And people were very upset. And they said, Marlee Matlin, offensive, question mark. And to this day, I still talk about it, because people still bring it up. I think it’s gotten less and less. But people still bring it up 30 years later. Whatever.

AH: Right, I mean, what did it feel like to be thrust with all of that, kind of having to be that representative?

MM: It was extremely hurtful. It really hurt my feelings because no one—I had never had the opportunity to understand why they were upset. I had never had the opportunity to understand why they felt the way they did. I didn’t understand it. No one took me aside to say, look Marlee, this is what you did, this is what we do, this is what see, this is what we think, this is what we feel, this is what we think of you, this is what we think you do right, this is what we think you do wrong. And it wasn’t fair. It wasn’t fair. It was sort of this crab theory thing. I mean I was at the top, so to speak, and the were all trying to tear me down. And I just decided to step away from the deaf community for a long time. I would say 10 to 15 years. I chose not to get involved whatsoever, and I just did my thing as an actor. And I slowly made my way back into the community and sort of look at it with a wary eye, because there’s a lot of politics involved there. I was raised to believe that you could do whatever you wanted to do, as long as you were comfortable, as long as you were doing what was right, and that we all fall but we all have the great opportunity to get back up on our feet again and achieve success.

AH: What improvements have you seen towards the Deaf community since you first started out?

MM: In film and television, or in general?

AH: Yeah, in film and television particularly. On screen.

MM: As you said, not everyone’s in love with Switched at Birth, and they’re entitled to their opinion. They can watch a show just like everybody else can watch whatever show they want, whether they’re deaf or hearing. But in terms of deaf actors, there are, as a result of the show, a great number of actors who’ve gotten the opportunity to work. And there was an entire deaf cast of hearing and deaf actors together in Spring Awakening on Broadway last year. Children of a Lesser God, then Big River, and then this is the third. So Spring Awakening. So there are more and more, but it’s not as fast as I’d like to see it. It’s been 30 years since I won the Oscar. You’d think something would have happened sooner. And there are still film and television shows that are casting hearing people to play deaf people. Um, and I think that a lot of the argument has to do with oh, we need to have international box office or we need to get—

AH: Yeah.

MM: It’s about box office. But I can say definitely that there are more deaf actors out there than there were in the past. It’s just still not, it doesn’t reach the level of equality when it comes to, you know, other actors when you’re talking about diversity.

AH: Yeah, I mean even just last year, when the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences announced their sort of initiative to change up their membership qualifications in response to Oscars So White, they addressed gender, they addressed race, sexuality—

MM, directly: Except deafness.

MM: Except deafness and disability. No mention of deafness or disability whatsoever. And that was very disappointing to me.

AH: I mean, I know you’ve been outspoken about that in the last year. Have you seen any sort of movement on behalf of the Academy?

MM: I don’t know. I don’t know if in the Academy they’ve addressed the point. I mean, I know that Cheryl Boone Isaacs is very open, and yet when I get the screeners for the Oscars, they’re not all captioned, so that means that people who have hearing loss or who are deaf or hard of hearing members of the Academy aren’t able to watch these screeners.

AH: Wow I didn’t realize that.

MM: I think that that’s important in order to vote. This year, when they did a retrospective of all the female actors who won best actress, they didn’t show Louise Fletcher signing her Oscars speech in sign language. They didn’t show me signing my Oscars speech. Um, Jane Fonda won signing her Oscars speech for Coming Home, they didn’t show that. They showed everybody else. And I don’t know why.

AH: Interesting.

MM: I don’t know why.

AH: Have you ever—I’m sure every person, I think anyone who’s not a straight white guy has probably at some point turned down roles they found demeaning or offensive. Have you ever done that? Roles that you felt would shine a not-so-positive light on—

MM: No, but there are some who should. There’s a movie coming out in the fall that had roles—it’s called Wonderstruck—and there are roles in there for deaf actors that I think they should have turned down the role because the lead actress who played the role is not deaf, but she’s playing a deaf person, and that’s all, I’m going to leave it at that.

AH: I mean, that’s happened to you quite a few times. I know you’ve talked about The Piano, you auditioned for it, or you at least spoke about trying out.

MM: Well, I mean, listen, in The Piano, she was casting a person who didn’t speak but who could hear. So the idea wasn’t that she was a deaf person, she was a person who was mute. So she didn’t have to speak. So the idea wasn’t about the casting of a hearing person in general; the idea was just open up your mind to allow a deaf person to allow somebody who’s not disabled

AH: Right.

MM: If you want to put it that way. So when confronted, they said it’ll be hard for the audience to believe that it’s Marlee Matlin who can hear on the role, because we know she’s deaf. And the argument was putting back to them was, do you believe that Al Pacino is blind in Scent of a Woman, do you believe Dustin Hoffman has Autism in Rain Man? It’s all the same. It works one way for a non-disabled to play disabled, but it doesn’t seem to work the other way.

AH: And kind of going back to the idea of you being a sort of representative and stepping into that role, when you’re on the set for new projects, especially if you’re working with people you haven’t necessarily worked with before, do you feel as though you have to both do your job as an actor but also serve as a sort of consultant to make sure things are happening right?

MM: No, that’s not my job. I’m a very outgoing and gregarious person, and I find you can do this all indirectly. I don’t have to teach them about it—well, I don’t know. Maybe they want to learn dirty signs in sign language, and I’ll teach them that. But I don’t feel like there should be any reservations about communications. I always have an interpreter on the set. Most people—people who work in the entertainment business are fairly experienced, and I’ve been around long enough that they know, and that for me you don’t have to worry about the phone, you can text me, you can send me a message, you shouldn’t talk to the interpreter directly and say, tell her. People pretty much know all this stuff by now. It’s not that hard to adapt, it takes a few seconds to make it happen. So, I don’t usually do that. But I’m not the person who teaches the other actors how to sign, that’s not my job, I’m the actor. But if they ask me questions, I’m more than happy to share information.

AH: Yeah.

MM: I mean, I’m a very approachable person.

AH: Yes, I have not met you, we are talking across two different coasts, but you seem very approachable.

MM, directly: Yeah.

AH: [laughs] Um, so the last question that I ask all of my guests on this show, I will ask to you, Marlee. And it is: can you recall the last time you saw something on screen, in a film, T.V. show, that you were not directly involved with where you felt as though you were represented, or you felt as if you saw yourself in that show, that character?

MM: That’s a very good question. Let me see. Ooh. Uh. [pause] I haven’t been watching a lot of T.V., which is a problem for me, lately. I’m more concerned about grades and getting them to volleyball or soccer practice, or, gosh. Um. Veep, Veep I love. Veep I love. And there’s something in there, this idea of the woman with the assistant who misunderstands her all the time. I think that’s kind of funny, that sometimes happens to me. But there hasn’t been anything that I find that reflects my experience.

JJ: I’m telling Marlee that she should be watching Big Little Lies, because that’s her wheelhouse. Big Little Lies is about mothers and kids and the things that go on behind, and I’m trying to encourage Marlee to watch—this is Jack speaking—and I think she would get a big kick out of it because it involves a lot of fantasies and it’s four very strong women actors, which we haven’t seen in a long time. This is Jack, going back to Marlee now.

MM: You know, all I can say is that when we’re talking about film or television, no one should ever be afraid to think of the idea of saying, you know what, why don’t we change it up a bit? Why don’t we put somebody in a wheelchair. Why don’t we put somebody who’s deaf? Why not? And if it doesn’t work, OK, move on. But give it a try. Remember, it works. It worked on the West Wing, it worked on the L-Word, it worked on Switched at Birth, it worked on Picket Fences, it worked on Law and Order: SVU. It works all the time. It just happens that it was always me, but you can use me or any number of deaf actors out there. It works.

AH: Yeah. Well thank you so much, Marlee, it was an honor to have you on. I’m just really happy we got to make this happen. And thank you, Jack, for helping us make it happen. It was great.

JJ: Thank you.

MM, directly: Thank you so much.

* * *

AH: That is all for today. My dear colleague Derreck, thanks for reminding us that Coming to America is both amazing and problematic all at once. And many thanks to Marlee and Jack for an incredibly insightful conversation. It was very much a pleasure.

*Update, April 8, 2017: In the introduction to this episode, Aisha Harris used an outdated term to refer to people with hearing loss. This has been updated in the episode's transcript and will be addressed in a future episode.