Searching for Saddam

Closing in on the "Fat Man."

As the infernal Iraqi summer came to a close, Rudman Ibrahim Omar al-Musslit and his brother Mohammad still proved remarkably difficult to locate. For Eric Maddox, the interrogator with the special operations forces in Tikrit, the first breakthrough of the fall came with the capture of Ahmed Yasin Omar al-Musslit. One of the youngest in a long line of Musslit cousins, Ahmed wasn't personally suspected of major insurgent activity. But two of his brothers, Nasir and Faris, were. It took Maddox six hours to get Ahmed talking about his relatives. He swore he hadn't seen Rudman in months, but he had seen Mohammad. And contrary to what most of the American analysts had believed, Ahmed claimed it was Mohammad, not Rudman, who was taking orders directly from Saddam.

Maddox was under pressure to make all of this network business amount to something. A new special forces team had arrived in October, giving him a new set of bosses for the remaining two months of his assignment. By this time, he'd become so intimately familiar with the players in the insurgency that the insurgents themselves had a nickname for him: "the man in the blue shirt." (Maddox had not brought an elaborate wardrobe to Tikrit, so he invariably wore the same blue Oxford day in and day out.) The commander of the replacement team, whom everyone called "Bam Bam," was a smart but cynical commander. This meant Maddox had to spend time winning over someone new—a leader who didn't quite understand the point of targeting people with no known role in the insurgency, just because they happened to be somebody's cousin.

Finally, on Nov. 8, Maddox had something to show for his work. On the same day, a 4th ID battalion snagged Faris Yasin, the brother of young Ahmed Yasin, and special operations nabbed Rudman Ibrahim himself. Rudman was flown to Baghdad against the wishes of the special ops team, who wanted to interrogate him right away. Still, it was the biggest score of the fall. And then, less than 24 hours after being captured, Rudman dropped dead of a coronary. "We were furious that he died on us," says Lt. Col. Steve Russell, the commander of the 1-22 Infantry. "I mean, think about it: He would have known Saddam's location."

It was a setback with a silver lining. After Rudman's death, the insurgency continued to operate with no apparent drop-off in efficiency. This suggested that Ahmed had been correct: Rudman Ibrahim Omar al-Musslit was not the mastermind—his brother Mohammad had been calling the shots all along. "We thought, until Rudman was captured, that Mohammad was maybe this security chief, or something like that, when in reality he was the chief operator," Russell says. "He was the main guy pulling everything together."

Overnight, everyone's focus shifted to Mohammad. Since his identity at the time was such a guarded secret, he became known to those hunting him as "Fat Man." The hunt was on, and more than ever the hunters were convinced that, if they found the Fat Man, Saddam Hussein would not be far behind.

I first met Eric Maddox on a rainy November day at a chili joint in Alexandria, Va. It was the day before he was to depart for another stint abroad as an interrogator, one of many since 2003.. He's a bulldoggish man, about 5-foot-9 with a strong handshake and a serious face that at first conceals his sense of humor. He does become quite animated, though, when you get him talking about social networking.

The reason social network diagrams are essential to counterinsurgency, Maddox says, is that they help you predict what will happen when someone like Rudman Ibrahim Omar al-Musslit gets killed or captured. By studying the relationships between potential targets, it's possible to make an educated guess about how the network will shift—most importantly, who will move up in the ranks—when someone is eliminated. "If you know all the relationships," Maddox said—marriages, family ties, who drinks together—"then the network does not behave irrationally."

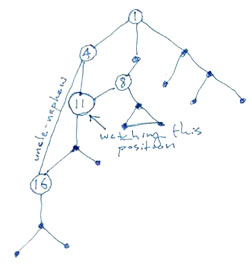

To illustrate how this all works, Maddox borrowed my legal pad and sketched out a dummy insurgency. His chart had about two dozen people, starting with a high-value target at the top. (Maddox emphatically reinforced his points by tracing lines with his pen, so the network ended up looking like an ink explosion. This is my re-creation of his drawing.)

The crux of Maddox's scenario is that one of the men near the top (No. 4) has a nephew (No. 16) with a low-level role in the insurgency. Catching and questioning the nephew could lead you to the top man, whose whereabouts are currently unknown. The trick, Maddox says, is to find someone in the network whose job, if he were eliminated, would fall to the nephew. Even if the nephew is not terribly important or experienced, the key is to understand that—particularly in Iraq—a familial bond is more important than any other relationship. If there's a sudden vacancy in an important job, there's a very good chance the man at the top will appoint his nephew to the role. Once the nephew comes out in the open, you can interrogate him and get to the uncle.

When Rudman fell out of the network, Maddox's hypothetical scenario came to pass. To fill in that huge gap, other members of the Musslit clan and their associates had to step up—a process that brought them out of the weeds and make them easier to capture. On Dec. 4, the 4th ID caught up with Burhan Ibrahim Omar al-Musslit, suspected of coordinating finances for the insurgency. A few days later, a young boy who served as an informant for Col. Jim Hickey led the Americans to a member of the family who had first helped Saddam when he fled the country in 1959.

Meanwhile, Rudman Ibrahim Omar al-Musslit's son had started to talk. Nicknamed "Baby Rudman," the 18-year-old had been picked up with his father and sent to Baghdad. After the elder Rudman died, Baby Rudman was flown back to Tikrit for questioning. Under interrogation by Maddox, he gave up two allies of Mohammad Ibrahim Omar al-Musslit: a business partner named Abu Drees and Basim Latif, Mohammed's driver. Still, it wasn't an easy sell to pick up two people because they were the alleged friends of a friend of Saddam. As Maddox recalls in his memoir, the team's analyst, "Kelly"— special operations members aren't identified by full name, since the Army keeps the elite team's operations secret—put it in blunt terms:

"Look," he said with an edge in his voice. "You keep going down on this fucking link diagram and we'll never get anywhere. We're supposed to be working our way up. But you're just adding names to the bottom of the list."

By good fortune, however, the 4th ID had already picked up Basim, the driver. For Maddox, putting the heat on Basim came with its own risks: He was the cousin to a high-ranking Tikriti security official, someone with whom the U.S. military needed to be on good working terms. After a first interrogation wasn't fruitful, Maddox tried again, with this second encounter taking place in the offices of the mayor of Tikrit, with much of the special ops team present. When the driver still wouldn't talk, special forces took him into custody.

At this point, Bam Bam, the special ops commander, was jeopardizing his career. Arresting Basim strained American relations with the Tikriti leadership, and the rewards would not be immediately apparent. But as insignificant as Basim seemed, he was only two degrees removed from Saddam himself. And that was the best lead Maddox had.

It would turn out to be one of the most important decisions the team would make. "He's the reason for the season," Maddox told me when we met, almost exactly six years later. After getting arrested, Basim did a 180, deciding that it was in his best interest to talk. He became intensely devoted to helping the Americans locate Mohammad Ibrahim, known then by the codename "Fat Man." If they found him, then they could only hope he was still in touch with the man they were really going after.

For days, the Americans were just a step behind the Fat Man. First they raided a rental house in nearby Samarra, where they missed their target but got his 18-year-old son, Musslit al-Musslit. A stash of $1.9 million in hundred dollar bills also strongly suggested they were on the right track. Musslit quickly broke down under questioning and pointed Maddox to a hatchery where his father and a friend often went fishing. The special ops team raided the fish farm twice, but once again the Fat Man slipped away. For their trouble, they picked up two nervous fishermen instead.

Time was up for Maddox; his assignment was about to expire. On Dec. 8, he returned to the Baghdad International Airport with a few cooperating prisoners in tow, including Basim. His first order of business was to interrogate the fisherman caught at the Fat Man's farm, who had been sent directly to Baghdad when captured. Maddox was due to leave Iraq in six days.

The fishermen were just the type of small fry that Kelly, the analyst in Tikrit, had worried about going after. Instead, they would offer proof that the networking approach really worked. One of the men, it turned out, was cousins with the Fat Man's fishing buddy, Mohammed Khudayr. The fisherman and his cousin owned a property in Baghdad as well, which he thought the Fat Man might use as a safe house. Maddox passed along the lead.

In one of the interrogator's last nights in Iraq, a major came by and casually mentioned a raid on a Baghdad home—the fisherman's safe house. A few hours later, the special ops men returned with four hooded prisoners, including Mohammed Khudayr. Once again, though, the Fat Man had eluded them. Just one more lead that had evaporated like so many others.

Earlier that day, Maddox had briefed the commander of the special ops task force on his link diagram and networking approach. The commander had been so impressed with Maddox that he'd booked the interrogator to brief CENTCOM's intelligence officer the next day in Doha, Qatar. His flight left at 8 a.m. At 2 a.m., just six hours before he was set to leave Iraq, Maddox started questioning Mohammed Khudayr. After a long back-and-forth, the man shocked Maddox by confessing that the Fat Man had been with him when he was captured. As soon as Maddox realized what this meant, he raced back to the prison and started pulling off the hoods of the other three men who'd been picked up that day. The third one was Mohammad Ibrahim Omar al-Musslit. They had found the Fat Man; it had just taken them a few hours to realize it.

Back in Tikrit, Maj. Brian Reed slapped a blank piece of butcher paper on a table. In about 15 minutes, Reed and his commanding officer, Col. Jim Hickey, sketched out a plan to capture Saddam. The Fat Man had given Maddox the location after only a few hours of questioning: a farm located along the Tigris near the town of al Dawr. This place had special significance for the dictator. In 1959, after he tried and failed to assassinate the then prime minister of Iraq, Saddam had fled to al Dawr before swimming across the Tigris into Syria. After he came to power, Saddam would restage that swim every year on the anniversary of his escape.

While Maddox was by now in Doha, Mohammad Ibrahim Omar al-Musslit was flown from Baghdad to Tikrit and then brought to the farm by the special ops team. From there, special ops rendezvoused with the 4th Infantry Division troops under Hickey's command. Reed says he thought this would be another "dry hole," just like every other tip on Saddam's whereabouts. Hickey felt more certain. After an initial scan of the property failed to turn up their target, Mohammad pointed out the spot on the ground under which Saddam's famous spider hole was concealed. The hunt for the most wanted man in Iraq was over.

Read Part 5: Network State of Mind.

Become a fan of Slate on Facebook. Follow us on Twitter.