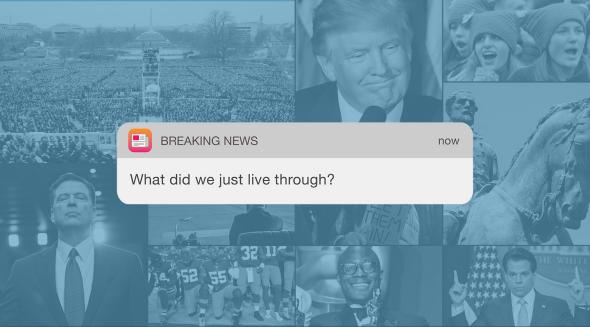

It has been an exhausting, exasperating, anxious year. A year of relentless assault, as one news break after another pushed its way into our daily existence and found us where we live, interrupting family dinners and drinks with friends, errands and work, rough patches and best-laid plans. No matter who you voted for or what your politics are, life changed the instant Donald Trump won. The information faucet turned on, gushing scoops and leaks and scandals, and never stopped.

Something happened to the news this year. It wasn’t only Trump. It was the convergence of Trump and technology and the media landscape, with the invigorated news giants and hungry digital outlets duking it out for our bloodshot eyeballs. And there was no better way to get our attention, to barge into our days with the latest revelation, than with a push alert. A bubble of news, just a sentence or two, to alter the course of your day.

Of course, it’s more than the push alerts. There’s Twitter, and the minor panic of checking it when you are in line at the grocery store or commuting home from the office—the dawning realization that Something Happened, the frantic search to determine what that something is and whether that something actually matters. There’s cable news: Shows that used to cover multiple stories over several segments now just roll on, hour to hour, with a rotating cast yelling about what the president said that day above an urgent chyron also yelling about what the president said that day. There’s Facebook and Slack and texts from your mom that say I’m just sick about what’s happening to this country. All of these things that toggled between pleasure and nuisance before Trump won are now insistent and suffocating, coming at us with such speed and ferocity that it feels impossible to escape. Maybe you stopped using Twitter. Maybe you turned off your notifications. Maybe you’ve sworn off CNN and taken up a hobby. Nice try. Another loose-lipped senior official is coming for you, and you will engage.

For all of our polarization and our partisan bubbles, this inability to detach from the news is something we’ve experienced together. Maybe you were reading a different enraging blog post than I was, or swiping an alert that I didn’t get, but we’ve all been checking our phones and waiting for the next big thing, for the president to tweet, for the sexual assault allegation just about to drop. We didn’t used to know what was said at every White House press briefing. We didn’t await word of the next mass shooting. We didn’t always wake up expecting news. The cadence of life has changed.

In an effort to understand this change, and the current news environment, we gathered all the breaking news push alerts that one outlet, the New York Times, sent from the moment Trump won until last Wednesday. Taken all together on the above interactive (or in the abbreviated video if you are reading this on mobile), the alerts provide a visceral snapshot of the year that was—the intense bursts of news, the slow days that seemed disorienting without a breaking story, the early morning pushes, the 5-p.m.-on-a-Friday pushes, the pushes of stories that never broke through, the pushes that were impossible to ignore. We hope you’ll take a few minutes to explore them and reflect on the crazy year, press the pause button when it feels overwhelming (because it will, and it was), and then read the essays below, which together illuminate the experience of being a consumer of, and in some cases producer of and commentator on, news this year.

Collecting a year of push alerts did not lead us to any grand conclusions about what we all just lived through. It is an ongoing investigation, as they say. Did the onslaught of news dull our ability to distinguish between what matters and what’s noise, or are we finally paying attention? Did we spend our time wisely, or waste it devouring what media and technology companies fed us? Will the pace of news eventually slow down and the phone stop vibrating and the rhythm of our days recalibrate—or is this how it will always be? We’re still too deep in the muck to know.

— Allison Benedikt

By Will Oremus

On Oct. 20, the New York Times’ push notifications team was worrying about “alert fatigue.” Video had just surfaced that disproved an incendiary claim made the day before by Trump’s chief of staff, John Kelly, about Rep. Frederica Wilson. The Times’ breaking news desk was treating it as a big story. But the small team of editors who decide which stories get pushed to the mobile devices of millions of readers was conflicted. “Alert fatigue,” said Eric Bishop, the Times assistant editor who leads its notification efforts, is what happens when readers decide that such notifications have become more of an annoyance than a service and deactivate them altogether. The draft of this particular alert read: “A Democratic Congresswoman said that President Trump’s chief of staff lied about her role in a 2015 ceremony. A video supported her account.” Ultimately, the team decided that the risk of boring, confusing, or otherwise irking readers outweighed the value of sending it.

In an age of nonstop news and widespread misinformation, push alerts have emerged as a way for media outlets from the Times to Fox News to BuzzFeed to convey their most urgent updates in the space of about 150 characters. At this point, the Times and the Washington Post—as the two newspapers on the front lines of the national news cycle—have both come to view alerts as essential to their editorial strategy and have top editors involved in crafting and approving them. Some news is obviously push-worthy: Paul Manafort is indicted, Michael Flynn is fired, there’s a mass shooting of historic proportions in Vegas. But some, like an inflammatory Trump tweet, is less clear. The editorial calculus involved in deciding which alerts to push and when, particularly in this unprecedented year, can be complicated.

The Times has actually been sending push alerts since at least 2011. In the early days, its mobile app had relatively few subscribers, and the paper’s editors treated push alerts as an afterthought. But in a time when print circulations are down and people increasingly get their news via social platforms, alerts are one of the last ways for publishers to reach their readers directly, in their own words and on their own terms. Take the 2016 Times alert that read: “After dark, President Obama spends hours alone, time he says is essential to think, write and have a snack—exactly 7 almonds.” That’s the kind of detail that the Times has found, through its analytics, can prompt more readers to swipe through to the story. These days, said Bishop, “Our push notifications [feel] a lot more like something you might say out loud—less like a headline and more like a tweet.”

Animation by Lisa Larson-Walker. Photos by Brendan Smialowski/AFP/Getty Images, David Becker/Getty Images, Carlos Barria/Reuters, Kevin Winter/Getty Images.

The past year’s news cycle has been so overwhelming that it has forced publications to think through their push alert strategies in new ways. Tessa Muggeridge, the Washington Post’s newsletter and alerts editor, told me that the Post has shifted from pushing a mix of breaking news and feature stories to pushing breaking news almost exclusively since Trump’s election. “My phone is constantly lighting up,” she said—which is why, in a crowded notifications era, the Post has responded by raising its gravitas threshold. “We’re purists on push alerts,” she explained. Human interest and whimsy, she said, are not priorities for them.

The Times, meanwhile, has intentionally retained a diverse topic mix in its alert selection—even at the risk of fatigue. “The most polarizing type of notification, based on the feedback we get from our audience, is sports game results,” Bishop said. “And award shows are probably a close second.” The August boxing bout between Floyd Mayweather and Conor McGregor was especially divisive, Bishop recalled. “We had a couple people going, ‘Just for one guy punching another guy, we’re going to send an alert?’ ” In the end, the Times opted to send it.

When it comes to breaking news, though, the two titan organizations are in a constant race with each other—one where push alerts are a part of the scoop. “Everyone’s core instinct is to beat the Post,” the Times’ Bishop told me. The Post’s Muggeridge said: “We measure the speed of all of our alerts, and we track exactly what our competitors are doing.” This is in keeping, she added, with the heavy emphasis on data and metrics that the paper has adopted under owner Jeff Bezos. Sometimes, a Post notification goes out before the related story is even live. Of course both push teams said that accuracy is the foremost concern. But editors at both papers also acknowledged that they keep rivals’ push alerts activated on their personal devices, which adds to the sense of urgency as they’re composing a notification. Bishop explained: “We’ll have Editor A saying, ‘Please, just send the alert, send the alert!’ And Editor B’s going, ‘No, we can make this better.’ And it’s aggravating for us that we’re sitting there looking at our lock screens,” knowing an alert on the same story from another paper could pop up at any moment.

For all the thought that both outlets put into their push alerts, neither was able to articulate precisely how they serve the paper’s bottom line. Are they meant primarily to drive traffic to the website? Or to increase subscriptions? Or simply to build the paper’s brand? Certainly they can give a huge boost to a story’s audience, Times news desk editor Michael Owen told me: “We get a bigger traffic spike from push alerts than we get from anything else.” Yet “there’s no direct payoff” from a given push alert “in terms of mission or business,” Owen said. “It’s really about the long game.”

Editors at both papers said they don’t have specific goals or quotas with respect to traffic, subscriptions, or the number of readers reached. And neither team can say with any certainty that its approach—the Post’s focus on politics and investigations, the Times’ desire to be a broad part of readers’ lives—works better than the other’s. In a journalism era marked by fast-changing metrics and instant gratification, this feels like a welcome uncertainty. Though push notifications may be a high-tech tool, in many ways they represent a return to old-fashioned news values.

There is one particular metric that both papers pay close attention to: the “swipe rate,” or the rate at which readers swipe through from an alert to the story itself. The results can be surprising. The Times’ most-swiped notification of 2017 so far, as of early October, was the one on July 21 announcing that Sean Spicer was out as White House press secretary. It may have helped that the alert included the detail that Spicer had expressed anger at Trump’s hiring of Anthony Scaramucci as his new communications director, Bishop speculated—and that the Times was the first to break that particular piece of news. The paper’s least-swiped alert? A May notification that Trump was scheduled to take his first foreign trip the following week, to the Middle East. Bishop said he doesn’t regret pushing it, though. “My thought on it was not, ‘Oh, this was a bad alert.’ It was just that this alert sort of had all the news you needed.”

By Stephen Sestanovich

“The Russia story” hung over this year like no other. Looking back at the Washington Post and New York Times’ Russia-related push alerts is like reading a conspiratorial thriller, with unexpected twists and explosive revelations but no clear ending in sight. They also remind anyone who thinks of the past year as one long, uninterrupted story about Russian meddling and collusion that coverage was actually kind of episodic. There were the initial reports of intelligence agencies confirming Russian interference and President Obama’s reaction. (One Times alert from Dec. 16, 2016: “President Obama defended his restrained response to hacking before the election but says he warned Russia, ‘We can do stuff to you.’ ”) There were a few days in February when nearly every alert was about a phone call between Michael Flynn and the Russian ambassador. There was a peak of media frenzy in the late spring and early summer, when FBI Director James Comey was fired, former FBI Director Robert Mueller was hired to investigate, and journalists started producing new revelations round the clock. (“The Russia story,” proclaimed a Times politics alert from July 11, “has become a brier patch from which President Trump cannot escape.”) And of course there was the most recent burst, with Mueller’s first indictments. But there were many months in which interest all but died away. In May there were 78 push notifications about Russia, more than a quarter of the total for the entire year. In April, there were seven.

Reading the alerts, and tracking the waves of coverage, makes very clear that the media never had the lead role in the Russia story. For all the energetic work of our best newspapers, very few big breaks were the product of real investigative reporting. They were generated by the enormous number of people in key institutions of the U.S. government—in the CIA and other intelligence services, in the FBI and other law enforcement agencies, in the Congress, and even in the White House itself—who were determined to make public what they knew about Russian support for the Trump campaign.

The reason we know that Trump asked Comey to end his investigation of former national security adviser Mike Flynn (trumpeted by the Times in a May 16 alert as an “Exclusive”) is that, after dining with the president, Comey himself wrote up a designed-to-be-leaked memo about it. We learned that Trump bragged about firing the FBI director to the Russian foreign minister only because someone at the White House wanted the world to know the president had called Comey a “nut job.” And why did Donald Trump Jr. release his entire email chain about meeting with Russians to get dirt on Hillary Clinton? (“Here it is,” exulted a July 11 Times alert.) Because sources with access to “confidential government records” went to the Times, who then told Trump Jr. they already had it.

Reporters didn’t have to go looking for this story—it came looking for them. The leaks were so abundant that newspapers could discard the old Woodward and Bernstein rule that you need two sources to confirm a story. In the Trump era, it’s routine to have 10 or 20. (Consider the Washington Post’s alert of May 11: “Before Comey’s firing, Trump’s animus toward the FBI director boiled over into fury, according to 31 officials’ accounts.”)

Trump would have a point if he said that the Post and Times basically confirm his worst fears about the “deep state.” They show the institutions of the U.S. government hemorrhaging one incriminating detail after another. Anyone who would like the federal bureaucracy—above all, our law enforcement and intelligence agencies—to be politically neutral has to wince at the memory of such uncontrolled and purposeful leaking. But wincing does not mean regretting. Under the circumstances, and with no good alternatives, the leakers did the right thing. The “deep state” can hardly expect to avoid partisanship if it lets itself become a tool for the abuse of presidential power. Those who’ve been telling the media what they know have done their bit, strange as it may sound, to keep themselves and their institutions out of politics.

By Bakari Sellers

In June 2015, four days after my friend and former colleague, Clementa Pinckney, was murdered by a white supremacist at AME Methodist Church in Charleston, South Carolina, CNN called to offer me the job of regular contributor. I’d just left the set of ABC’s This Week, where I’d discussed the tragedy with Martha Raddatz. In the previous few days, I had broken down in tears on Al Jazeera, talked about my father’s days in the civil rights movement on MSNBC, and wondered aloud if the country could heal on CNN. It had been a grueling week. But faced with CNN’s offer, I said yes. I was grateful for the platform. I had no idea what the next two years would bring.

When I accepted the CNN gig, I believed that Charleston would be the nadir of our country’s struggle with race during my lifetime. I was wrong. Before Trump became president, I imagined that my job was to sound the alarm about his sordid history with race and his utter disdain for the poor. I was in the CNN studio preparing to go on State of the Union when then-candidate Trump refused to disavow David Duke in February 2016. Watching it live, I was dumbfounded. When I went on the air beside former NAACP President Ben Jealous, Tennessee Rep. Marsha Blackburn, and commentator S.E. Cupp, I wanted to make clear that Trump was leveraging racism as currency with the Mississippi primary looming. I stated as plainly as I could: “The country’s getting browner. … You have to be able to reach out to these other minority groups, these other coalitions if you’re going to be president of the United States. And Donald Trump has built a wall figuratively and literally.”

In the months leading up to November, I lost count of how many times, on how many different shows, I ran through Trump’s pattern of discrimination in housing or with dealers in Atlantic City or the Central Park Five. Needless to say, it didn’t matter: In the end, 62 million voters, many driven by cultural anxiety, were willing to set aside Trump’s history of racial animus.

Then the election happened. On Nov. 9, I was as shocked as everyone else, but my job was to go on television and answer the question “what happened?” I was hungover from a night of sorrow drinking and it was hard to even summon the words to articulate my feelings. In January, I was on TV for hours during the inauguration. I did my best to give Trump his day. We were perched above 101 Constitution Ave. in D.C., and the weather was dreary—rainy and cold. My most vivid memory is watching Hillary arrive in her suffragette white. I listened to Trump’s dystopian view of our country, and it dawned on me that my task was no longer to advocate for a candidate but to explain why our new president’s words and deeds are simply the antithesis of what I understand America to be.

Animation by Lisa Larson-Walker. Photo by Samuel Corum/Anadolu Agency/Getty Images.

This has been my mission as a TV commentator since, facing an administration that has repeatedly demonstrated how little it cares about people of color. In April, former CNN analyst Jeffrey Lord and I debated the merits of Lord’s belief that “Donald Trump is the Martin Luther King of health care,” an assertion I believe to be asinine, ahistorical, and devoid of merit. In September, conservative commentator Paris Dennard and I spent two segments dissecting the topic of NFL players kneeling during the national anthem. Dennard argued that the players were anti-American and should choose another means of protest, while I argued that these players embodied the best of America, pushing us to be a more perfect union.

Both Jeffrey and Paris are good guys. I consider them friends. To dismiss them as either anti-intellectual or racist would be a disservice to this country. The fact is that Lord and Dennard speak for a large number of Americans. My goal was not to change their minds but to give viewers my perspective and my experience. I didn’t want to dismiss or shut down people like Lord and Dennard so much as I wanted to contextualize them, to offer viewers a fuller, more balanced picture of our national psychology. While our conversations have some root in traditional partisan politics, each time I’m on television, I hope that these debates force Americans to grapple with the more important question of what we want our common values system to be.

As a commentator, I’ve often been unable to hide my emotion and, frankly speaking, my pain. Frequently the call to appear on-air comes the day of, and there’s little time to prepare, let alone sort through my feelings. The No. 1 question about my work that I get from people is, “How do you do it?” I take that question to mean: How do you not explode with frustration when having a debate with someone who refuses to acknowledge your views or agree on the basic facts? For me, there are a few answers to this. Before I’m a pundit or a Democrat, I’m a black man in America, and I refuse to be made to be angry. I do, however, get tired. I get exhausted. At the lowest moments, when Trump is claiming “violence on many sides” or attacking Gold Star mothers, I remember Obama singing “Amazing Grace” at my friend Clementa’s funeral. I feel lucky to have an opportunity to give a voice to those who have been screaming for years but remain unheard. After the cameras are off and I leave the studio, I return home to kiss my wife and daughter, I fix a Deep Eddy’s grapefruit and soda water, and I rest easy. I know the president tweets at 6 a.m., and soon I’ll be called to offer my voice again.

By Reihan Salam

There was a time when it wasn’t immediately clear what prominent people thought about a given issue, and so we had the space to think for ourselves. That time has passed. Now, before we even have the chance to read the story that some push or tweet or Gchat has alerted us to, a consensus has formed about it on the left and on the right. There is a correct opinion and very little room for dissent. That, to me, has been the hardest part of the Trump-era news onslaught: Whereas I once enjoyed lots of vigorous constructive conversations with friends and friendly acquaintances who don’t share my (mostly conservative) beliefs, such conversations have grown rare. Political exchanges are either tribal affirmation sessions or they’re shouting matches. The space in between seems to have vanished.

Political scientists Christopher Achen and Larry Bartels are known for their work on the “group theory of democracy,” i.e., the notion that people choose their political loyalties not on the basis of a dispassionate weighing of the evidence, but rather as a function of group attachments. What kind of person am I, or do I aspire to be? Who champions the causes people like me care about? Group theory has helped me make sense of political phenomena I’d otherwise find mysterious. For example, there is no essential connection between believing that fracking is evil, border control is racist, and adopting a single-payer health care system will drastically reduce health care costs. Yet I’ve found that the kind of person who believes one of these claims tends to believe the others, too, because that’s what “people like them” believe.

Until recently, though, I knew many people who defied such easy categorization. I spent most of the George W. Bush years in Washington, D.C., where many of my close friends were right-wing contrarians of one sort or another, before spending the Barack Obama years in New York City, where I was mostly surrounded by self-identified liberals and leftists. The nation’s capital at the time was home to a large, squabbling, and fairly intellectually diverse GOP bubble; and though conservatives were harder to find in New York, I met lots of quirky left-wing dissenters with whom to bat around ideas.

There’s much less of that now. I meet fewer and fewer people who see themselves as culturally and politically ambidextrous. Everyone I come across seems to know exactly what they think about every new headline. They all know exactly which side they’re on, almost instantly, and seem wary of being out-of-step with their ostensible allies and friends. One obvious explanation for this is that the rise of Donald Trump, the most polarizing figure in modern political history, has raised the stakes of the political debate. I buy that.

But Trump is only part of the story. Twitter, among other social media tools, allows us to know exactly what our heroes think and, by extension, what we ought to think. It also lets us know which quirky dissenters we should be hounding at any given moment lest anyone suspect we agree with them. My problem with the current news environment is not so much that it’s exhausting: It’s more that it seems to have transformed some of the most interesting people I know into talking point–spouting zombies.

By Leon Neyfakh

Dorothy Fortenberry, a Los Angeles–based playwright and screenwriter, tried to go cold turkey after the 2016 election. For years, she had been a voracious media hound, relentlessly scrolling through Twitter and maintaining a daily regimen of reporting, magazine journalism, and commentary. Once Trump became president, she decided she’d had enough. But Fortenberry couldn’t restrain herself. Her mind would go to the news even when she didn’t want it to. At yoga, she’d find herself imagining war. In the mornings, she’d wake up in a panic over what horrible thing might have happened while she slept. Soon she was mainlining media again, grasping for a sense of control over events that felt both remote and acutely urgent.

For Fortenberry and others like her, being addicted to current events has never felt more self-destructive. “I can be in the middle of, you know, a normal dinner or something,” Fortenberry said, “and all of a sudden I’ll get an alert on my phone or I’ll sort of idly decide to check it. And then I’ll just feel a bit like I got jumped by the news.”

It used to be that keeping up on world events was a marker of maturity and seriousness. It meant you were curious enough to follow the incremental ways in which history unfolded day by day. The news was often boring back then, and keeping track of it required a certain level of intellectual energy and rigor. With Trump as president, this has all changed: Now the news alternates between reality show and B-movie, and keeping track of it all—the utterly inconsequential palace intrigue, the speculation about what’s going to happen next—feels like eating junk food that’s been seasoned with poison. And yet for many, there’s still an irresistible pull. At a moment when breaking news is constant and chaotic, what used to be a more or less benign, even edifying, habit has turned into a life-consuming affliction.

TQ White, a 65-year-old father of two who lives in Minnesota, has always proudly identified as a news obsessive. But these days, reading up on whatever’s happening in the world causes him to experience a wave of self-loathing: “I get this attack of bitterness and regret that I don’t like. Sometimes it actually feels like I’m an alcoholic slipping.” As a computer programmer, White said, he gets frequent 30-second breaks while the software he’s working on is loading, rendering, and searching—and during those tiny intervals he feels helplessly drawn to the news. “[I’ll see a] tweet about some bizarre behavior,” he said in an email. “Look at the article. Click through to another article. Post that on Twitter. Get a like. Look at that person’s feed. See another take on how awful Trump is. Click on it. Feel guilty. Try to focus on work. Someone walks into my office and says, ‘Can you believe that Gorsuch says …’ And so on.” During the first few months of the administration, White said, he was losing approximately half of his work time falling down these miserable holes.

Animation and photo by Lisa Larson-Walker

Matthew Coffey, 32, who works in finance in Tampa, Florida, said the news now seeps into all corners of his life, too. “My group of friends, they’re not the most politically engaged guys,” he said. “I was always the one who read the news. But now if we go to the bar and have a couple drinks, it’s coming up.” Before the election, he was a compulsive news follower and a habitual Fox News watcher—Bill O’Reilly’s show in particular. Now, he still reads constantly but has tried to stay away from cable TV. “You throw on MSNBC and it’s just so silly,” Coffey said. “It’s like, I get it, the guy’s a liar.” Even conservative pundits exhaust him now: “They’re so repetitive,” he said. And yet often he’ll be working and suddenly catch a glimpse on the office TV of Trump speaking and find himself staring all over again. “He says the same thing every time, it’s a joke,” Coffey said. “But there’s a reason why everyone loves to put him on TV.”

This gets to what is perhaps the most insidious thing about Trump’s grip on the time and attention of news addicts: how good he is at conjuring darkly entertaining storylines. “I think … what keeps me coming back is the shock value,” Fortenberry said. “In the boring Marco Rubio version of this story, I would still be consuming news but I don’t know that it would feel exciting—I think it would just feel grim. This feels exciting and grim, in a weird Walking Dead kind of way.”

Needless to say, Fortenberry recognizes that, unlike The Walking Dead, there are hugely high stakes here, and they are far higher for the people Trump has been directly targeting. Indeed, the fact that all of the news she is getting pelted with is so unequivocally real—the threat of a nuclear strike against North Korea, the travel ban, the violently revolving door in the West Wing—has made it harder for Fortenberry to stay invested in some of the more quotidian aspects of her own family life. “Like, the thing my 2-year-old wants to do is pour one cup of water into another cup of water for 45 minutes,” she said. “That’s sort of beautiful and contemplative, but it’s also kind of … lame.”

By Dahlia Lithwick

I’ve written about the courts for 18 years, and the first 17 of them were pretty good for my health. No matter who was in power, the justice system was focused and coherent, and even legal moves that threatened civil liberties, like the Patriot Act and the torture memos, lent themselves to clear and reasoned arguments and could be manageably covered by reporters. That has changed in the past year. Not just in terms of the pace of legal news but in the way my job itself has become destabilized. Most days now, journalism itself is in the news. It’s reality that seems to be slipping away.

We knew from the start that Donald Trump had nothing but contempt for the rule of law. But the imperatives of law and of journalism are the same—words matter, truth-seeking matters, testing presumptions against facts matters. By the time Trump was elected, it was clear that both law and journalism could falter if norms around truth and language were shattered, if we had to spend our time picking through barrels of lies for any semblance of truth. I didn’t expect that every major move by the administration, from the travel ban to the trans ban, would be done by sloppy lawyers doing bad work, rolled out in tweets and TV spots. That was the real surprise. This wasn’t a D.C. policy battle. It was a cage match against falsehood. The challenge for me as a reporter in the first months of the Trump era was to try to make the case that language still had meaning, that presidential tweets held the force of law, and that truth was still knowable. Every day was a graduate-level class in ontology.

Before the election, I filed a few stories a week, hosted a podcast, gave speeches, and tried to assume that most journalists and lawyers with whom I disagreed were acting in good faith most of the time. I thought of my job as a kind of ambassador between the courts and the public; I wanted people to understand the courts and love the law as I did. Since the election, my job has turned into a kind of ferocious act of public gargling: drink from the daily firehose of alarming information, audibly slosh it around, spit, rinse, repeat. Not a day goes by when I am unaware that the combination of law and journalism might bring America back to sanity. Every single night I go to sleep feeling I didn't do enough to explain and worry about the collapse of legal norms.

Join Emily Bazelon, John Dickerson, and David Plotz as they discuss and debate the week’s biggest political news.

Through most of this period, I was living in Charlottesville, Virginia, which we think of now as “Charlottesville” but at the time was just home. While I was watching round after round of Tiki torches and white nationalists invading and bullying, I was patiently extolling the virtues of the Supreme Court’s landmark ruling in the Skokie case and telling people that free speech mattered for the same reason truth and law matter: because bad ideas aired in public spaces eventually disappear. But it seems, at least after the violence of Aug. 12, that I was wrong about this as well. I have found my faith in the institutions I’d spent my career explaining and defending—courts, law enforcement, journalism, and government—shaken. And I have often found myself, as a parent and as a neighbor and as a journalist, speechless.

My biggest fear about journalism in our time has been that the same cults of personality, branding, and false intimacy that created Donald Trump can also corrode the central values of reporting. When I go out in the world to write stories, I try to evaporate the me that fixes my kids’ lunches or monitors my nephew’s hockey stats. But it is not possible anymore to disaggregate the “me” that reports on gender discrimination from the “me too” horrified at the raft of stories of powerful men assaulting women. It’s not possible to separate the faith I practice from the grotesque parody of faith that allows Roy Moore, now a candidate for the U.S. Senate, to flout the separation of church and state. It’s not possible to watch the all-out war on contraception and abortion without filtering it though my own lived experiences with miscarriage and childbirth. In an America that has drawn its fault lines through identity politics, it’s tempting to believe journalism must still be performed with no lens of identity. But the daily drumbeat of hate directed at women, religious minorities, immigrants—and the hourly distortion of the legal machinery we had constructed to protect against it—cannot always be separated from the journalism we do.

This is what it means now to live the news. That the borders between concerns are collapsing, leaving no refuge, is a product of this critical moment. The boundaries between home and away, between public and private, were a luxury we no longer have. I now believe that the people who continue to have faith in law and in journalism are the most vulnerable to the cascade of lying that pours forth from the White House and the Justice Department. Lying destabilizes both endeavors in ways that make us feel that they cannot be practiced at all. But the unrelenting pace of the news, of the work of making it and of spurring it on, has shown that the power of words still matters to people. Slowing down should be the last thing we do.