“Not My Choir”

By agreeing to sing at Trump’s inauguration, the Mormon Tabernacle Choir has enraged many Mormons and forced a reckoning over the LDS church’s values.

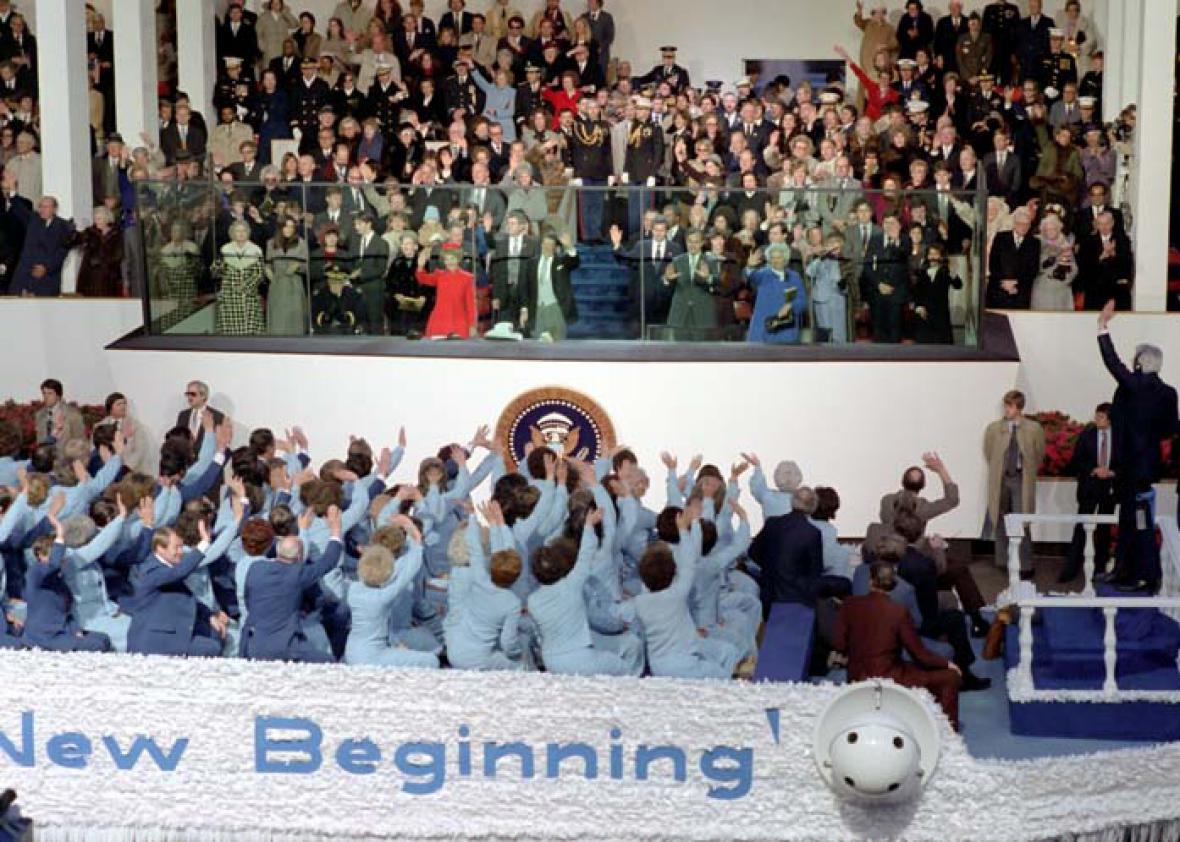

Reagan Library

For much of 2016, Donald Trump’s bombast seemed to be breaking open an unprecedented fissure between the Mormons and the Republican Party that the mogul acquired in a hostile takeover during the presidential primary. And so it came as an unwelcome shock to many anti-Trump Mormons when the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS) announced in December that some 200 members of the Tabernacle Choir—the Mormons’ most prized public-relations asset—would lend their voices to celebrate the inauguration of President Trump.

This Mormon–Trump alliance was not supposed to be. Last summer and into the fall, gleeful reports from anti-Trump news outlets (including this one) highlighted Trump’s problems with the most reliably Republican religious voters in the U.S. The Mormons, who know something about state-sponsored religious persecution, chafed at Trump’s Muslim ban. They were appalled at Trump’s willingness to denigrate immigrants from Mexico as “criminals” and “rapists.” (Mexico is home to more Mormons than any country outside of the U.S.) Following the release of the Access Hollywood tape in October, the Deseret News—the LDS church’s newspaper of record—joined a chorus of Mormon elected officials calling for Trump to drop out of the presidential race. Evan McMullin, a former CIA agent, a former policy director for the House Republican Conference, and himself a Latter-day Saint, launched a moonshot independent presidential bid from Utah. By presenting himself to his fellow co-religionists as the conservative alternative to Trump, McMullin hoped to peel off enough Trump-resistant Mormons to prevent Utah from going red. In a close Electoral College contest, the “Utah strategy” proponents theorized, losing Utah’s six electoral votes just might deny Trump the White House.

Even a few weeks before Nov. 8, hopes for a McMullin miracle were still alive. One Utah poll had McMullin with the lead in a three-way race among McMullin, Trump, and Clinton. But on Election Day, enough Utah Mormons showed that they were still Republicans. And though he underperformed Mitt Romney, who took the state with 72.6 percent of the vote in 2012, Trump easily won Utah, 45 percent to Clinton’s 27 percent and McMullin’s 21 percent. “My tribe verged on courage,” one Mormon friend said, “and then slunk back to being evangelicals who don’t drink.”

But in late December, the headache of Trump’s Utah victory turned to heartache for anti-Trump Mormons. Just before Christmas, the church announced that its beloved Tabernacle Choir—which in the 20th century helped make Mormon synonymous with American through its long-running radio program and performances at previous presidential inaugurations—had accepted an invitation to sing at Trump’s inauguration. Elton John had reportedly said no. So had Celine Dion. But the choir said yes. (A church spokesman told me that the church has never turned down an offer to sing at a presidential event, be it an inauguration or another function.) Thus, on Friday, 200 or so Latter-day Saints will participate, along with an America’s Got Talent runner-up and some (but not all) Rockettes, in the elevation of Trump to the highest office in the land. They will reportedly sing one song, “America, the Beautiful.”

Instead of creating a fissure between Mormons and Trump, the choir’s decision to honor a man whom many church members consider a white-nationalist demagogue has created a rift among Mormons themselves. This wasn’t just about singing. The controversy over the choir speaks to deep, unresolved issues in the church regarding race, the Mormon people’s own history of persecution, and the persecution that Trump has already promised to visit on others.

Immediately after the church made the announcement, distraught Latter-day Saints took to social media to denounce the move. “Not my choir” and similar sentiments echoed the “not my president” postings elsewhere. At his blog, Benjamin Park, a historian of American religion and a Latter-day Saint, offered an apology to those “who have been the direct targets of Trump’s attacks. I hope you know that [the choir’s] appearance at Trump’s inauguration does not reflect my values or interests, nor many of my friends and family within the Mormon tradition.” Park rejected the notion put forth by the LDS church public affairs office that singing at the inauguration does not imply support for this particular president, nor is it “an implied support of party affiliations or politics.” “This is not an inauguration for either of the Bushes or Reagan,” Park wrote, referring to three of the presidents at whose inaugurations the choir had sung. “Rather, it is an inauguration for a man who spews racist garbage, brags about abusing women, and boasts about a Muslim registry. This act makes the Church’s appeals for religious liberty, gender equality, and international peace prove hollow.” As of this writing, more than 35,000 people have signed an online petition demanding that the choir back out of the inauguration.

Perhaps most notably, soprano Jan Chamberlain (who voted for Evan McMullin) resigned from the choir instead of participating in the inauguration. In her resignation letter, which went viral after she posted it to Facebook, Chamberlain wrote that her choice was based on morality, not politics. “I could never ‘throw roses to Hitler.’ And I certainly could never sing for him,” Chamberlain wrote.

Chamberlain has said that she’s received a great deal of support for her decision to quit, and to do so publicly. Yet other Mormons have called her move unpatriotic. Some even call on her and those who share her views to resign from the LDS church altogether. Brain Hales, a former member of the choir who sang at George W. Bush’s inauguration, told me that Chamberlain “has reached thousands” with her anti-Trump stance because she leveraged her membership with the choir, which he considers a violation of “trust” among choir members who “give up the ability … to be an activist” when they agree to join. Hales, who also didn’t vote for Trump, believes that if Chamberlain felt so strongly, she should have resigned quietly instead of bringing “negative publicity to the Church.”

Chamberlain’s resignation has gotten the most press coverage. But another choir member, Cristi Ford Brazao posted a video to Facebook explaining why she’s glad that she’ll be singing at the inauguration. The video has received more than 160,000 views. However, for Brazao—a black convert who grew up in Natchez, Mississippi, who also did not vote for Trump—the precedent for the “bravery” that she’ll draw on to sing at such a controversial event will not come from past performances of the Tabernacle Choir. Instead she’ll look to the strength of “the Tuskegee Airmen and Buffalo Soldiers who served this country at a time when [the country] was so divided.” Most poignantly, Brazao will look to “Marian Anderson … who sung at two inaugurations at a time in this country when she couldn’t even walk in the front door of a building where she was performing her own concert because of the color of her skin.” Brazao explained that she’s “grateful for Marian’s decision to sing at those inaugurations because know I have her example to turn today.”

Brazao’s take on the choir controversy embodies the tension that the choir, the LDS church, and the United States writ large face as the nation transitions from Obama to Trump: from America’s first black presidency—a progressive, pluralistic, and internationally engaged presidency—to a president who ran a campaign built on belligerent and nostalgic isolationism and promises to restore white Christian men to their place of unrivaled political and cultural hegemony. Many of those Mormons who don’t want the choir to sing for Trump want their church to cut its ties with the white supremacy upon which, to a large degree, their church and the nation that birthed it were built. Those Mormons want their faith to reflect the present and future of the church in which most Mormons are not white and not even American. (More than half of the 15 million members of the LDS church live outside the U.S., with the greatest growth rates in Africa, the African diaspora, and Latin America.)

But the church’s decision to allow the choir to sing at the inauguration reflects a continuity with the recent Mormon past; throughout the 20th century, the church used the choir to secure Mormons’ place in white America, a period when the Mormons were certainly not considered Christian and not even always white. As historian W. Paul Reeve recently argued in his award-winning book Religion of a Different Color: Race and the Mormon Struggle for Whiteness, even after the LDS church officially abandoned polygamy in 1890, white Protestant America viewed Mormons as less than white—the result of the unholy marital and procreative alliances that produced racially denigrated offspring. Many in the American mainstream viewed Mormons as “physically different and racially more similar to marginalized groups than they were to white people,” Reeve explains. “Mormons were conflated with nearly every other ‘problem’ group in the nineteenth century—blacks, Indians, immigrants, and Chinese—a way to color them less white by association.” Like other not-quite-white cultural and ethnic minorities— the Jews, the Irish, and the Italians—Mormons highlighted their whiteness by contrasting it with African-American blackness, through blackface minstrelsy performances and even occasional acts of anti-black violence. Perhaps most effectively—and in the end most troubling—the Mormons embraced various racist doctrines, which among other things held that people of African descent were marked with biblical curses and which propped up the chuch’s racist practice of excluding black people from full membership. By virtue of being anti-black, “Mormon” identity became synonymous with “white.” Only in 1978, after the highest-ranking leaders had received a revelation to do so, did the church lift its ban on black men from holding the priesthood and on black men and women from performing the most sacred Mormon rituals in Mormon temples.

The Tabernacle Choir was also inextricably connected with the work of moving the Mormons from the “wrong” to the right “side of white,” as Reeve puts it. George Pyper, the manager of the church-owned Salt Lake Theatre, which served as the longtime home to many Mormon minstrel troupes, was also manager of the choir in 1911, when it completed its first grand tour of the eastern United States, including performances at Madison Square Garden and at the White House for President Taft.

Ronald Reagan famously dubbed it “America’s choir” when the Tabernacle Choir sang at his 1981 inauguration. But as Michael Hicks—author of The Mormon Tabernacle Choir: A Biography and who teaches music at Brigham Young University—explained to me, the choir had unofficially earned that moniker long before: “The choir’s start on radio was almost synchronous with the stock market crash,” in 1929. And the choir, with its blend of patriotic music and spoken-word performances, created “a spiritual outpost for a nation stumbling into the Great Depression.” For the next four decades, the choir’s “Music and Spoken Word” program, directed and announced by Mormon apostle Richard L. Evans, and broadcast weekly from Temple Square in Salt Lake into millions of American homes across the country, addressed “American ideals of God and country,” Hicks told me. Though occasionally he’d quote from Mormon scripture, “these were public service announcements more than religious programming” designed to unite an American nation often fractured by economic uncertainties, racial strife, and unpopular wars.

The choir became a commercial and critical success when, in 1959, its rendition of the “Battle Hymn of the Republic” reached No. 13 on the Billboard Top 40 and won a Grammy the next year. However, in 1964, then-church president David O. McKay described the invitation to sing at Lyndon Johnson’s inauguration as the “greatest single honor that has come to the Tabernacle Choir.” Since then, the choir has become the de facto house band for presidential inaugurations. (Well, for Republican ones, at least. Since 1964, it has performed at the first inaugurations of every Republican president, but no Democrats.) It’s a role that the choir and its church have relished.

The Tabernacle Choir remained all-white until Wynetta Martin and Marilyn Yuille, two of the handful of black Americans who joined the church before 1978, became the first black choir members in 1970. The choir surely understood the racial and political subtext of Sen. Charles Schumer’s not-so-subtle joke when he announced at President Obama’s second inauguration in 2013 that the “award-winning Tabernacle Choir”—“the Brooklyn Tabernacle Choir”—would serenade the president. Here was an (almost) all-black choir replacing an (almost) all-white choir on the inaugural dais, and the symbolism of the moment was made even starker by the choice of song: the “Battle Hymn of the Republic,” the song with which the Mormon Tabernacle Choir is most associated. Four years later, as President Trump takes office and works to implement an agenda to make a certain part of America a certain kind of great again, “the choir will certainly be glad to be back” at the inauguration, Hicks told me. “In accepting the invitation, there is a sense: make the choir great again.”

But according to Hicks, ironically, there is more greatness to be lost than gained in performing for Trump. “The choir pursued hard-fought respectability for Mormonism in America,” he said. “Now Trump is trading on that respectability, cloaking himself in ‘America’s choir’ when he’s not earned that respect himself.” Hicks disagrees with the decision to sing, not just because of Trump and his “unmanageable baggage, which the choir will now be associated with in the eyes of many.” Hicks thinks that the choir shouldn’t perform for any American presidential inauguration. “The choir should reflect a greater vision for the church,” which includes the increasing racial and international diversity of the church and the choir itself. “Remember, we left the United States” to escape religious persecution, Hicks explained to me. According to Hicks, it’s time to return to that history and have the choir leave the label “America’s choir” behind to focus on “promoting peace and harmony around the world.”

And yet, the church and the many Mormons who support the choir’s decision to perform at the inauguration see the act as the choir’s Christian duty. “What I’m trying to do as a person is to be like Jesus Christ,” Brazao said in her Facebook video. “Jesus Christ associated with prostitutes, liars, and thieves. While he did not endorse what they were doing, he didn’t withhold his mission from them. My mission is one of love, peace, and hope. And I want to share that with others even in the face of ridicule because that’s what Jesus Christ did.” Likewise, LDS Church spokesman Eric Hawkins suggested it is also the choir’s patriotic duty to sing as “a demonstration of our support for freedom, civility, and the peaceful transfer of power.”

Neither candidate Trump nor President-elect Trump has shown much regard for freedom, civility, or the peaceful transfer of power. Time will tell if the LDS church will stand up to President Trump when he implements policies that threaten the American democratic order. Who knows at that point if anyone will listen to the church that in a literal sense sang for the new president.