The Insurgent

Ted Cruz is leading the most ambitious national campaign no one sees coming.

Photo by Jonathan Ernst/Reuters

Ted Cruz could be president.

This sounds like a gag, or at least, the lead to a truism: Anyone could be president, if they run. But it’s serious. Texas Sen. Ted Cruz, the accomplished, theatrical avatar of grassroots conservatives, has a real shot at winning the presidency of the United States.

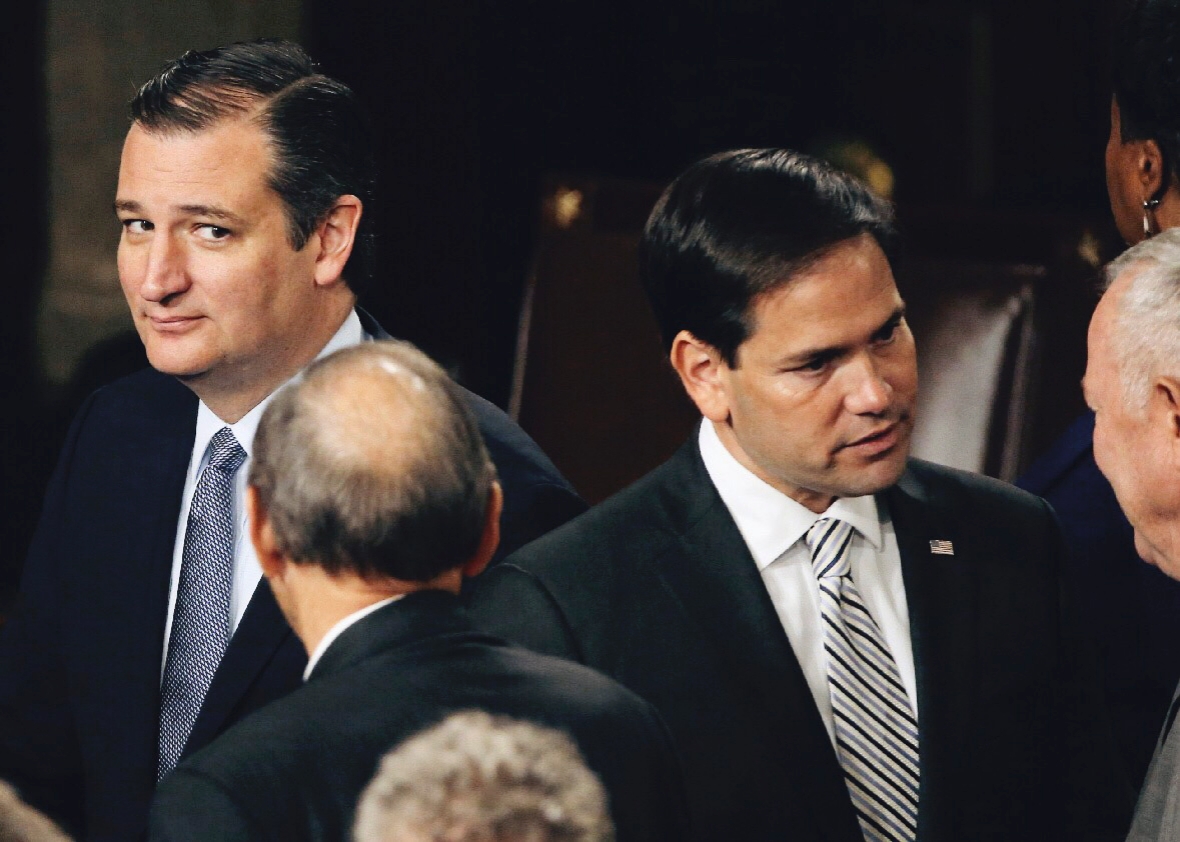

In the sprawling race for the 2016 Republican nomination, just a few candidates stand as “plausible” nominees—people who could win the primary, and thus, could stand against the Democratic Party nominee in a general election. At the “most plausible” end are Jeb Bush and Sen. Marco Rubio, who fit the mold of the kinds of people that parties, and the GOP in particular, nominate. After a series of poor, listless debate performances, Bush has almost collapsed, with shrinking support from voters and increasingly, donors. By contrast, Rubio—pushed along by his own skill as well as Bush’s failure—is surging into pole position as the front-runner. He’s moved forward in the polls, won new attention from GOP billionairies, and scored endorsements from fellow Republican lawmakers.

At the other end are the vanity and factional candidates—people running to represent an interest group, a constituency, or just because they can. Celebrity mogul Donald Trump and former neurosurgeon Ben Carson are still leading the national Republican polls, but given their problems—everything from extreme views to scant political experience—it’s difficult to see how they consolidate the GOP behind their campaigns for the nomination. Carly Fiorina, Gov. John Kasich, Sen. Rand Paul, Gov. Chris Christie, and Mike Huckabee have supporters, but in the face of stronger competitors with more cash and resources, it’s hard to see how they pull to the front.

And then there’s Cruz, who was one of the first Republicans to announce his bid for the White House. A self-proclaimed “outsider,” he’s been on the inside of national Republican politics for the past 15 years. He worked on George W. Bush’s 2000 presidential campaign as a domestic policy adviser and served in the Bush administration as associate deputy attorney general in the Justice Department and director of policy planning in the Federal Trade Commission. He spent five years as solicitor general of Texas, before winning his Senate seat in 2012.

Since entering the public eye, Cruz has made a splash two ways. First, with his palpable intelligence. Any given Cruz bit is peppered with references to political philosophy (he likes to mention John Rawls), American history, and occasionally Russian revolutionary politics. And while it can sound contrived, conservative audiences seem to love the senator’s erudite approach to political conflict.

Second, and related, is his heated, almost bombastic rhetoric. “I am convinced we are facing the epic battle of our generation,” said Cruz on the stump in his 2011 primary fight against then–Texas Lt Gov. David Dewhurst. “Which candidate is best prepared to stand up and lead the fight to stop the Obama agenda?” He carried this style into the Senate. In his first year, he launched a marathon speech against the Affordable Care Act, condemning it as a scourge on the fabric of America. “[Obamacare] is a job-killing, economy-destroying, health care ruining, debt-exploding, out of control government mess,” he said at one point in the performance. “Obamacare is all about socialistic control of we the people and nothing to do with fixing health care.”

As per his rhetoric, Cruz has led grassroots conservatives to shut down the government and has stood on the outside of the Senate Republican caucus as a gadfly of sorts, burning bridges with powerful party figures—on one occasion, he denounced Majority Leader Mitch McConnell as a liar on the Senate floor.

All of this has shaped Ted Cruz into an unusual national figure. With degrees from Princeton University and Harvard Law School, ties to the Bush administration, and a seat in the United States Senate, Cruz has the definition of an establishment résumé. Indeed, to the extent that he relies on this inside knowledge to sell himself to grassroots voters—“Republican donors actively despise our base”—he wouldn’t be Cruz without it. But he’s also despised by GOP leaders and other Republican senators. “Ted has chosen to make this really personal and chosen to call people dishonest in leadership and call them names, which really goes against the decorum and also against the rules of the Senate, and as a consequence he can’t get anything done legislatively,” explained Sen. Paul last month, after he called Cruz “pretty much done for” in the Senate. Cruz was a self-proclaimed “outsider.” Now, he really is outside the party.

Given this, it’s hard to look at Cruz and his presidential campaign and see a winner. The kinds of people who eventually stand for a general election aren’t the people who oppose party leadership and stand far to the right of the median voter. But we shouldn’t underestimate the junior senator from Texas. Yes, Cruz is disliked by fellow Republicans and seemingly eclipsed by rivals like Rubio. At the same time, he has a path to victory.

Photo by James Lawler Duggan/Reuters

To get a sense of what it could look like, it’s worth a jump back to 2008, when Sen. Barack Obama was fighting a tough insurgent battle for the Democratic nomination against Hillary Clinton.

Heading into Super Tuesday, in the 2008 Democratic primary, Clinton and Obama were almost evenly matched. After a bruising loss in Iowa, Clinton had picked up New Hampshire and Nevada. Obama, on the other hand, matched his caucus victory with a huge win in South Carolina. The then–Illinois senator led with delegates, but not by much. A strong Super Tuesday would give Clinton an edge in votes, in delegates, and in the ephemeral advantage of “momentum.” And given her place in the election—the “establishment” candidate of the race—observers assumed an edge for Clinton ahead of the Super Tuesday primaries, which were national in scope.

“It’s now essentially a media war, with Obama and Clinton competing in sound bites and 30-second ads,” wrote the New York Daily News ahead of the multistate contest. “Polls show Clinton leading in the Feb. 5 states with the top prizes, most notably California and New York, which have about 30 percent of the convention votes needed to secure the nomination.”

“The sprawling nature of the Feb. 5 event will test the candidates’ ability to draw votes under an array of different systems of voter participation,” wrote Rhodes Cook for Larry Sabato’s Crystal Ball at the University of Virginia’s Center for Politics. “In short, Super Tuesday will test the candidates’ organizational ability, campaign skills, and most importantly, their vote-getting appeal, in far-flung settings unique in their scope and variety.”

Super Tuesday came, and while Clinton won the most votes, Obama won the most states and scored the most delegates. It wasn’t the beginning of the end for the Clinton effort—that would come with the subsequent contests in Washington, the District of Columbia, Maryland, and Virginia, where Obama expanded his delegate lead into something almost insurmountable—but more than Iowa or South Carolina, it marked the Illinois senator as a truly national competitor.

Moreover, it established a strategy for overtaking a favored candidate with formidable resources and institutional support. Obama’s Super Tuesday success was a function of organizing. While Team Clinton focused on polls and television ads, the Obama campaign made heavy investment in grassroots and local organizing in small (but critical) states. Months of finding supporters, recruiting volunteers, and building infrastructure paid off on election night, where Obama could maximize his gains in favorable (or otherwise neglected) territory and minimize his losses in the large states that backed Clinton. Obama wouldn’t win a clean victory with this strategic, delegate-centered campaign—the 2008 race was a grind that lasted to the end of the primary calendar—but he would win. And that’s what mattered.

It’s tempting to place Rubio in the Obama position, for obvious reasons. He’s a young, non-white senator with a compelling story and a silver tongue. But Rubio isn’t running an Obama-esque campaign. He doesn’t draw large crowds; until recently, he hasn’t had strong fundraising; and he spends relatively little time in Iowa and New Hampshire, in contrast to Obama, who devoted his early campaign to massive organizing in both states. The key difference is that Rubio isn’t running an insurgent campaign. He’s running, instead, to supplant Jeb Bush as the candidate of the Republican establishment. And if he can do that—and consolidate establishment support—he can stand as the most likely choice for the nomination.

Cruz, on the other hand, is running an insurgent campaign, and it looks a lot like Obama’s. The most serious obstacle to running outside the party establishment is cash. Absent huge sums to organize and build camp across multiple states, there’s almost no way to turn popularity into votes. Obama solved this problem by merging unprecedented grassroots fundraising with traditonal big dollar donations. Cruz is doing the same. In the first half of this year, billionaires and other supporters put more than $37 million into his super PACs while Cruz raised $14 million through small donations to his campaign. The campaign, reports the Washington Post, has 219 “bundlers” who have raised $9 million, as well as 120,000 small donors. Together, this $51 million puts him ahead of everyone other than Bush.

What has Cruz done with this hefty war chest of direct contributions? He’s carefully managed it—at last count, he has $13.8 million “on hand,” more than any other GOP candidate—and invested in infrastructure. The Cruz campaign has invested much of its resources into “high-tech fundraising efforts” and building local organizations in states like Alabama, Georgia, Nevada, Oklahoma, South Carolina, and Tennessee.

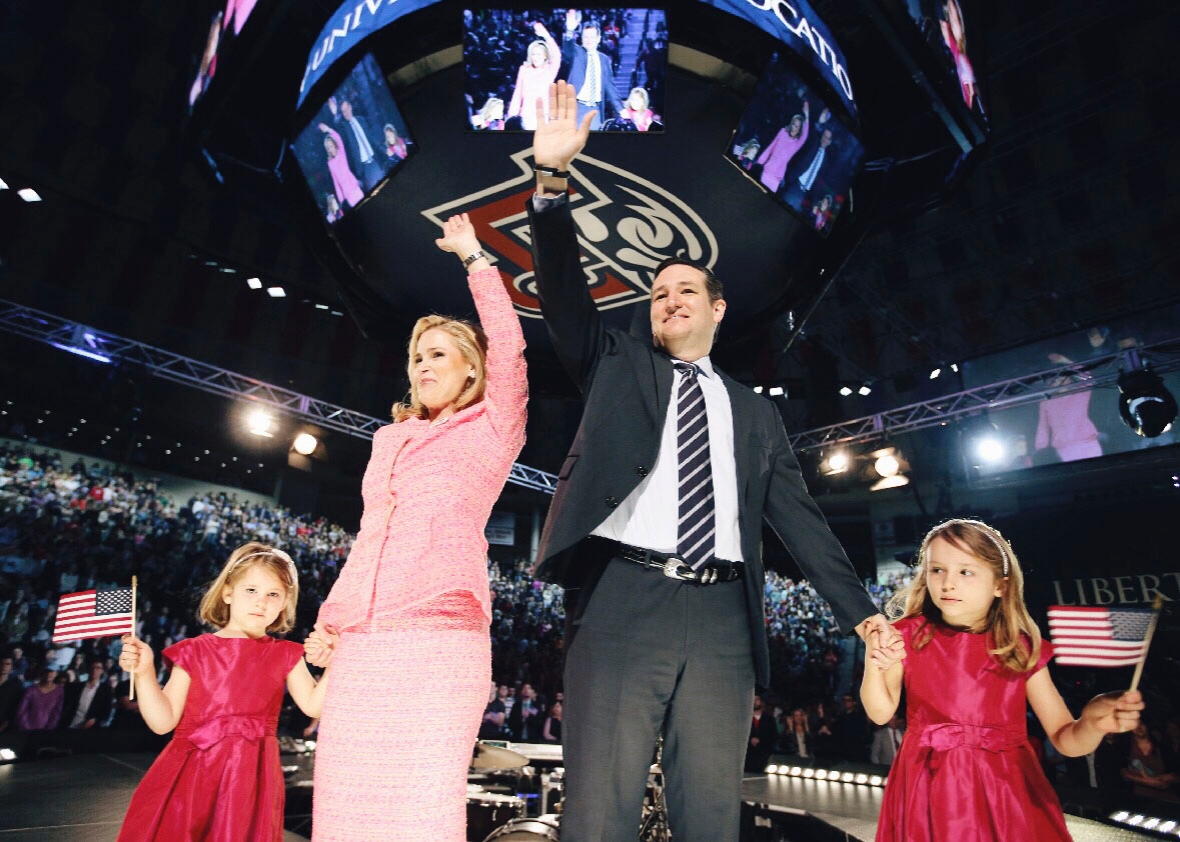

Photo by Richard Ellis/Getty Images

There’s a reason for this strategy. After the Iowa caucuses and New Hampshire primary, the next contests are largely in the South. Called the “SEC primary”—a nod to the collegiate Southeastern Conference—it begins on March 1 with Super Tuesday and ends two weeks later. During that time, Republicans will allocate more than two-thirds of all delegates, with a heavy portion from Southern and Western states, the geographic base of the conservative movement.

Cruz has spent his entire career courting these voters. He captures their mood and speaks to their concerns in a way unmatched by anyone else on the Republican presidential stage. “We need to stop surrendering and start standing for our principles,” he said during the second Republican presidential debate.

More concretely, he’s also done the actual work of reaching out to them: hiring paid staff, making regular trips through Southern states, and strategically reaching out to core demographics like evangelicals. Cruz, remember, announced his campaign at Liberty University in Lynchburg, Virginia, and will hold a rally at Bob Jones University in Greenville, South Carolina, later this month. What’s more, he’s reached out to key evangelical leaders, like Tony Perkins of the Family Research Council.

His overall message hits on issues central to these voters. If he’s not attacking the Affordable Care Act, he’s attacking Planned Parenthood. If he’s not attacking Planned Parenthood, he’s slamming Supreme Court decisions on same-sex marriage and defending “religious liberty,” and if he’s not speaking on social issues, he’s circling back to Washington as fundamentally hostile to their communities and their concerns. “We got a Republican House, we’ve got a Republican Senate, and we don’t have leaders who honor their commitments,” he said in the first GOP debate, echoing grassroots frustrations. “I will always tell the truth and do what I said I would do.”

With all of that said, how does Cruz actually win? First, strong, or potentially strong, competitors need to continue to leave the stage. The end of Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker’s presidential campaign was a tremendous boost for Cruz, who had one less opponent in his “lane” of the Republican primary. On the other hand, Donald Trump is dominating among voters who want an “outsider” while Ben Carson is grabbing a large share of evangelical voters, who are attracted to his strongly religious message. Cruz has been careful to defend and support both candidates, in hopes that—should they fall—their voters will move to his campaign.

It’s hard to say whether either Trump or Carson will leave before voting begins, but even if they don’t, Cruz isn’t lost. He’s on track to do well in Iowa, where he’s third behind Carson and Trump. If he can hold that position, or even move to second, he’s in a good spot for the similarly conservative primaries in Nevada and South Carolina. Key to his strategy, again like Obama’s in 2008, is surviving the rough spots and maximizing delegate wins. With campaign infrastructure in the South and momentum from Iowa, Nevada, and South Carolina, Cruz could finish the Super Tuesday and the “SEC primary” with a commanding plurality of delegates.

In this scenario, he’s strong enough to muscle out competing anti-establishment candidates like Louisiana Gov. Bobby Jindal and former Arkansas Gov. Mike Huckabee, assuming they haven’t left the race already. And it’s even possible that Trump and Carson will have left by this point, opening another pool of voters for Cruz to absorb.

Of course, this also assumes that Cruz—or someone like him—is the second choice for those voters. And that’s tough to say. Existing evidence suggests that a sizable portion of Trump and Carson voters would support Bush or Rubio if their candidates left the race. Which makes some sense; Cruz is an ideological candidate with supporters who see themselves, primarily, as conservatives. Both Trump and Carson, by contrast, tap into beliefs and frustrations that cut across ideology, and attract voters who might call themselves “moderates” relative to other candidates.

Which is to say that the other major question of the post–Super Tuesday race is what the establishment “lane” is doing. If it’s just Rubio or Bush, then it’s possible that either of them could consolidate enough mainstream support to win outright, like Mitt Romney did in the 2012 primary. But if there’s more than one establishment figure—most likely Rubio and Bush, but also possibly Christie and Kasich—then they could split the vote and give Cruz a path to the front.

Photo by Chris Keane/Reuters

This is truer if they split the vote in Northeastern and Rust Belt states where GOP primary rules advantage moderates over conservatives—it takes fewer votes to win delegates in New York City (because of the paltry number of GOP voters) than it does in Birmingham, Alabama. As FiveThirtyEight notes, “if a hard-right candidate like Cruz dominates deeply red Southern districts in the SEC primary, a more electable candidate like Rubio could quickly erase that deficit by quietly piling up smaller raw-vote wins in more liberal urban and coastal districts.” (Although, on that score, it’s worth noting the degree to which Cruz is campaigning in territories and other places where it’s easier to collect delegates.)

There are a lot of “ifs” here. But you can say the same for Rubio, who has been dubbed the front-runner in the race. What’s important is that Cruz is well positioned to take advantage of the “ifs” that go his way and survive the ones that don’t. And there is a decent chance that, in three months, both Rubio and Cruz will stand as the strongest candidates from their sides of the Republican Party.

In which case, we have a grinding, difficult Republican primary. And, like Obama was, it’s one Cruz is prepared to win. I said, at the beginning, that Ted Cruz could become president. The calculation is straightforward: If Cruz can fight to a matchup with Rubio, he has a strong shot at the nomination. If he wins that, then—by definition—the White House is possible. And before you assure yourself that Cruz could never beat the eventual Democratic nominee, consider this: Only one candidate in 50 years has won a third consecutive term for their party. If the economy is a little weak, and people are unhappy, then yes: Ted Cruz could be president.