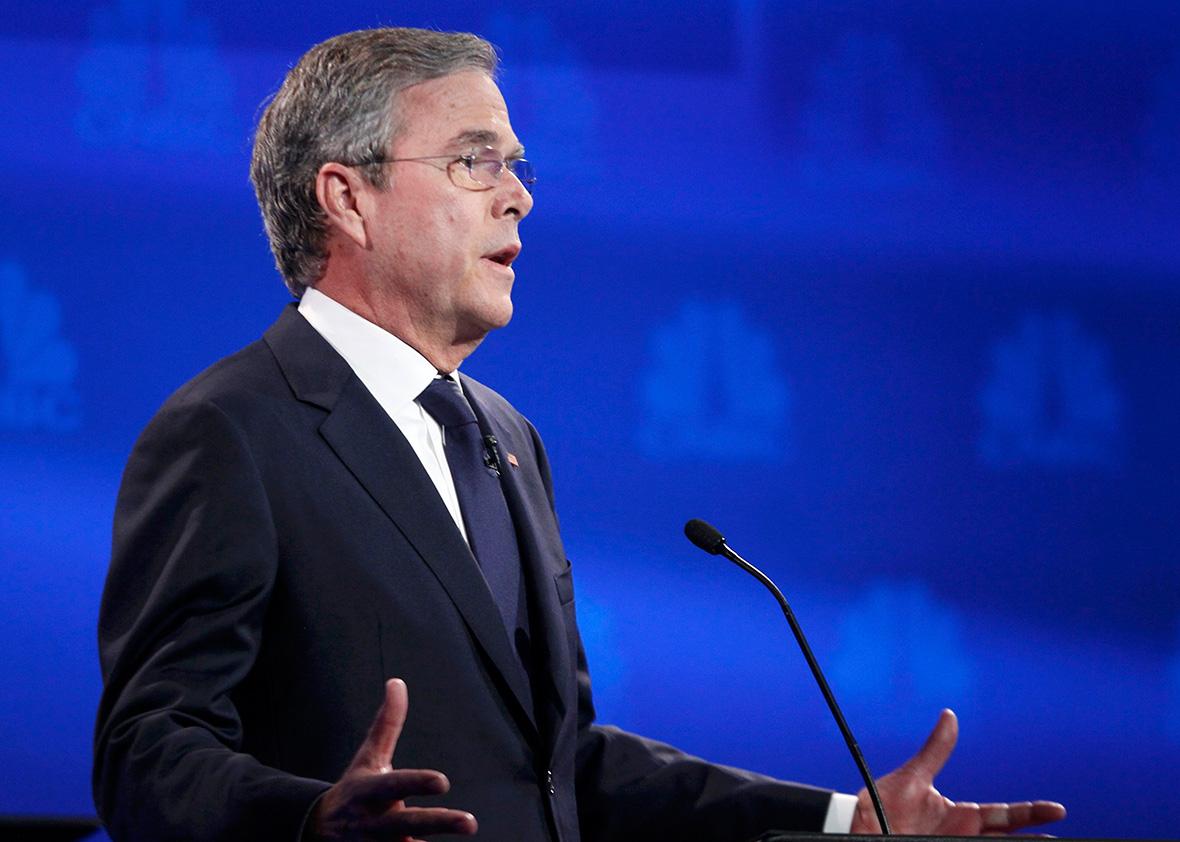

Wednesday’s Republican presidential debate was critical for Jeb Bush. He had to show donors and voters that he was a fighter, with life in his campaign—that he could stand up to Donald Trump, take on Sen. Marco Rubio, and emerge as a front-runner for the GOP nomination.

In other words, it was do or die. And Bush died. The debate clock tells the whole story; next to Sen. Rand Paul, who fell to the bottom, Bush had the least speaking time of any candidate on stage. Worse, he was on the losing end of a tough exchange. Early in the night, the former Florida governor came out swinging against his erstwhile protégé, Rubio. “Marco, when you signed up for this, this was a six-year term, and you should be showing up to work,” said Bush, hitting Rubio on his absence from the U.S. Senate. “You can campaign, or just resign and let someone else take the job.”

Bush had a hit. Rubio was supposed to stumble. But he didn’t. Instead, he accused Bush of playing politics in the most brutal way possible.

Well, it’s interesting. Over the last few weeks, I’ve listened to Jeb as he walked around the country and said that you’re modeling your campaign after John McCain, that you’re going to launch a furious comeback the way he did, by fighting hard in New Hampshire and places like that, carrying your own bag at the airport. You know how many votes John McCain missed when he was carrying out that furious comeback that you’re now modeling after?

[L]et me tell you. I don’t remember you ever complaining about John McCain’s vote record. The only reason why you’re doing it now is because we’re running for the same position, and someone has convinced you that attacking me is going to help you.

And that was it. Bush was finished. He spoke again throughout the night, but never with energy. Any wind he had—any fire or spirit—was gone. In a few seconds, Rubio had knocked Bush out of the game completely.

Put differently, if this was an “establishment” debate—hosted by CNBC, focused on the economy, and meant to give voice to the most viable candidates in the race—then it served its purpose. Bush might have cash reserves and support from family backers, but after tonight, he’s slipped to the second tier. He may not leave the race, but he’ll struggle to get traction. Now, Rubio—who gave another great performance—takes his place as the most viable candidate in the race, and as the closest thing to a front-runner.

But he’ll have rivals. Like Rubio, Sen. Ted Cruz excelled on this stage. But where Rubio turned to biography to win applause and plaudits—reminding the audience that he has struggled with student loans and personal debt—Cruz turned to an old saw. He attacked the media. Constantly. “The questions that have been asked so far in this debate illustrate why the American people don’t trust the media,” he declared in response to a question on compromise and the recent budget deal in Washington. “How about talking about the substantive issues the people care about?”

The crowd went wild, Cruz returned to this theme, dodging questions with hits on the moderators. And as they lost control over the debate—struggling to keep candidates on time and to ask follow-up questions—other candidates did the same, slamming the “liberal media” at the pro-business, pro–Wall Street CNBC. Cruz doesn’t just leave Wednesday in good shape; if he gets a boost in the polls, he has a campaign that can capitalize on his gains.

With that said, it’s important not to get lost in the theater criticism of presidential debates. This was supposed to be on the economy, and while it jumped into issues such as same-sex marriage and marijuana legalization, that was largely true. And after the modest but steady gains of the Obama administration where is the Republican Party on growth, wages, and economic security?

The same place it’s always been. As with Mitt Romney’s campaign in 2012, the signature policy plan for every Republican candidate is a tax cut. “We need somebody who can lead. We need somebody who can balance budgets, cut taxes,” said Ohio Gov. John Kasich, touting his record. “We’re reducing taxes to 15 percent. We’re bringing corporate taxes down, bringing money back in, corporate inversions,” said Donald Trump. “Growth is the answer,” declared Cruz. “And as Reagan demonstrated, if we cut taxes, we can bring back growth.” And the cuts are meant for high earners. Under Rubio’s plan, for example, the government wouldn’t tax income from dividends and capital gains, largely benefiting the wealthiest Americans. And while Rubio includes measures that benefit the bottom 10 percent of income earners, the overall effect of his supply-side cuts is to tilt the tax code toward the top at an even greater angle than exists now.

There’s more: Gov. Chris Christie called for Social Security benefit cuts and demogogued the program as broke (despite all evidence to the contrary) while Sen. Rand Paul and Ben Carson pitched the audience on their plans to slash Medicare benefits. Carson called for a flat tax, Cruz praised “sound money” and the gold standard, and Carly Fiorina attacked the federal minimum wage as unconstitutional. Candidates talked about their modest upbringings but couldn’t articulate plans for reducing student loans and debt. At most, Kasich pointed to online education, Bush pointed to “accountability,” and Rubio promised more vocational training.

In short, despite years of decrying Romney’s “47 percent” remarks, Republicans have stuck with the underlying idea: that the government does too much to redistribute wealth to low- and middle-income Americans, and too little to assist the richest citizens.

Which puts the GOP in an odd place. It has a strong candidate in Rubio, but it also wants to burden him with an unpopular message, rejected in the previous presidential election. And while Republicans can change course, the pressure of the GOP primary—which comes from the right, more than anywhere else—means that it almost certainly won’t.