The Fraud of War

U.S. troops in Iraq and Afghanistan have stolen tens of millions through bribery, theft, and rigged contracts.

Photo by Carlos Barria/Reuters

U.S. Army Specialist Stephanie Charboneau sat at the center of a complex trucking network in Forward Operating Base Fenty near the Afghanistan-Pakistan border that distributed daily tens of thousands of gallons of what troops called “liquid gold”: the refined petroleum that fueled the international coalition’s vehicles, planes, and generators.

A prominent sign in the base read: “The Army Won’t Go If The Fuel Don’t Flow.” But Charboneau, 31, a mother of two from Washington state, felt alienated after a supervisor’s harsh rebuke. Her work was a dreary routine of recording fuel deliveries in a computer and escorting trucks past a gate. But it was soon to take a dark turn into high-value crime.

She began an affair with a civilian, Jonathan Hightower, who worked for a Pentagon contractor that distributed fuel from Fenty, and one day in March 2010 he told her about “this thing going on” at other U.S. military bases around Afghanistan, she recalled in a recent telephone interview.

Troops were selling the U.S. military’s fuel to Afghan locals on the side, and pocketing the proceeds. When Hightower suggested they start doing the same, Charboneau said, she agreed.

In so doing, Charboneau contributed to thefts by U.S. military personnel of at least $15 million worth of fuel since the start of the U.S. war in Afghanistan. And eventually she became one of at least 115 enlisted personnel and military officers convicted since 2005 of committing theft, bribery, and contract-rigging crimes valued at $52 million during their deployments in Afghanistan and Iraq, according to a comprehensive tally of court records by the Center for Public Integrity.

Many of these crimes grew out of shortcomings in the military’s management of the deployments that experts say are still present: a heavy dependence on cash transactions, a hasty award process for high-value contracts, loose and harried oversight within the ranks, and a regional culture of corruption that proved seductive to the Americans troops transplanted there.

Charboneau, whose Facebook posts reveal a bright-eyed woman with a shoulder tattoo and a huge grin, snuggling with pets and celebrating the 2015 New Year with her children in Seattle Seahawks jerseys, now sits in Carswell federal prison in Fort Worth, Texas, serving a seven-year sentence for her crime.

Additional crimes by military personnel are still under investigation, and some court records remain partly under seal. The magnitude of additional losses from fraud, waste, and abuse by contractors, civilians, and allied foreign troops in Afghanistan has never been tallied, but officials probing such crimes say the total is in the billions of dollars. And those who investigate and prosecute military wrongdoing say the convictions so far constitute a small portion of the crimes they think were committed by U.S. military personnel in the two countries.

Former Special Inspector General for Iraq Reconstruction Stuart Bowen, who served as the principal watchdog for wrongdoing in Iraq from 2004 to 2013, said he suspected “the fraud … among U.S. military personnel and contractors was much higher” than what he and his colleagues were able to prosecute. John F. Sopko, his contemporary counterpart in Afghanistan, said his agency has probably uncovered less than half of the fraud committed by members of the military in Afghanistan.

Photo by Nikola Solic/Reuters

As of February, he said he had 327 active investigations still under way, involving 31 members of the military. “You don’t appreciate how much money is being stolen in Afghanistan until you go over there,” said Sopko, who says price-fixing and other forms of financial corruption are rampant in Afghanistan.

These and other experts, as well as some of those who have pleaded guilty to criminal wrongdoing, point to some recurrent patterns in the corrupt activity, which in turn illustrate the special challenges created when a sizable military force is deployed abroad. Sometimes ill-trained military personnel were forced to handle or oversee large cash transactions, in a region where casual corruption in financial dealings—bribes, kickbacks, and petty theft—was commonplace. Commanding officers, they add, were typically so distracted by urgent war challenges that they could not carefully check for missing fuel or contractor kickbacks.

So far, officers account for approximately four-fifths of the value of the fraud committed by military personnel in Iraq, while in Afghanistan, the ratio was flipped, with enlistees accounting for roughly the same portion, according to the Center for Public Integrity’s tally. The reasons for the difference are unclear. But Sopko said he expects more officers to be investigated for misconduct in Afghanistan as the U.S. military mission there continues, so the ratio could change.

The Pentagon wasn’t just defeated by the country’s graft—the Pentagon made it worse.

Troops who had little or no prior criminal history, like Charboneau, say the circumstances of their deployments made stealing with impunity look easy, and so they made decisions that to their surprise eventually brought them prison sentences ranging from three months to more than 17 years. Many, like Charboneau, were savvy about the military’s way of doing things—her mother, her first husband, and her second husband were service members, according to a statement her lawyer, Dennis Hartley, filed on Jan. 30, 2014, before her sentencing.

They say that they knew of other military personnel who also broke the law, but without getting caught. Hightower convinced her to steal fuel from Fenty, Charboneau said, by pointing out that the troops at nearby bases “aren’t getting caught, so you shouldn’t have to worry about it.”

Retired Army Reserve Maj. Glenn MacDonald, editor-in-chief of the website MilitaryCorruption.com, said the volume and value of fraud committed by troops in Afghanistan and Iraq seem higher to him than what he recalled as a young soldier in Vietnam in the 1960s. “What you can make out of these [recent] wars is staggering. It’s an opportunity for anybody, even a noncommissioned officer, to become very rich overnight,” MacDonald said.

Many have probably been tempted, he said, because they saw others getting away with the theft of thousands or even millions of dollars.

Pocketing thousands in cash from illicit fuel sales

Military fuel in Iraq and Afghanistan has been a perennial target of theft during the past 14 years of war. In Afghanistan, fuel moved around the country in “jingle trucks,” tankers adorned with kaleidoscopic patterns and metal ornaments. At Fenty, for example, jingle trucks bearing fuel arrived every few days from suppliers in Pakistan, all driven by locals under contracts with the base. Officers at Fenty then distributed it to 32 nearby bases, with the largest ones using up to 2 million gallons of fuel a week.

Photo by Lucas Jackson/Reuters

To describe the system as loosely controlled might be an understatement: Standard contracts allowed each driver to take seven days to bring the fuel to a destination that might be only a few hours away, according to Army Maj. Jonathan McDougal, who oversaw motor vehicle logistics in northeast Afghanistan in 2010 and 2011 from Bagram Airfield. “It was like they planned for something to go wrong with every convoy,” McDougal told the Center for Public Integrity.

Charboneau’s role in the Fenty fuel theft ring was simple. She ordered trucks to transport more fuel than needed, then filed fake records showing the extra fuel had been delivered to a base. After leaving Fenty in a convoy, the extra trucks diverted their loads to prearranged meeting spots, where buyers offloaded the fuel and paid in cash, with the proceeds divided later among Charboneau and her co-conspirators. The scheme worked—for a while—because the fuel storage amounts and truck delivery amounts matched (although of course the bases’ records of delivered fuel did not).

This represented, Charboneau said, “a big gap” in the fuel oversight system. And the rewards were enticing—about $5,000 in net profit from a single extra truckload.

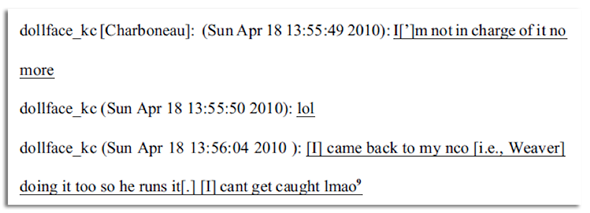

One month after she joined the scheme, according to the government’s sentencing memo, filed on Jan. 15, 2014, in U.S. District Court in Colorado, her supervisor, Sgt. Christopher Weaver, jumped in. She described the widening of the conspiracy in instant messages intended for her sister in Colorado, sent using the screen name “dollface_kc”:

Although prosecutor Mark Dubester said in the sentencing memo that Charboneau’s use of the term lmao (Internet slang for “laughing my ass off”) demonstrated that she “saw humor in the situation,” Charboneau said she did not. When she returned to Fenty, she said, Weaver pulled her aside and told her that he knew how everything worked, and while he had not made much money off of the scheme so far, it would be wise of her to keep her mouth shut.

“It was … one of those things that, ‘if you tell anybody, you’re probably going to be sorry,’” said Charboneau. “I was his subordinate. He was in charge.”

“Thereafter, the conspiracy continued with all three involved, and this is when the bulk of the thefts occurred,” according to the sentencing memo that Dubester submitted. Weaver met with Charboneau and Hightower each morning to decide which trucks would make legitimate deliveries and which trucks were “going to go get stolen,” Charboneau said in the interview.

If someone had simply asked more questions about the deliveries—such as “‘I need to know where you’re sending these 15 trucks. Oh, you don’t have a destination for these five?”—it would have been much harder to pull off the scheme, Charboneau said. She, Weaver, and Hightower were able to continue stealing as long as they did, she said, because they were the only three people entrusted with keeping track of where the fuel went when it left the base.

Digital monitoring could also have stopped theft at military bases, she said. Scanning the fingerprints of the drivers when they left Fenty and arrived at the destination bases, for instance, would have deterred them from selling it on the side, according to Charboneau.

Weaver pleaded guilty to counts of conspiracy and bribery on Oct. 10, 2012, and is now serving a sentence of three years and one month in a federal prison in South Dakota. His former attorney declined to speak on the record about the case. In a letter to Chief U.S. District Judge Marcia Krieger that Weaver filed with an October 2013 sentencing statement, Weaver wrote that he had originally taken the money to hire a lawyer because his “child’s mother was threatening to take my son away from me.”

“Of course, I took more than was needed,” he added. “I got greedy once I started.”

Hightower also pleaded guilty to conspiring to defraud the United States and was sentenced on Oct. 28, 2013, to two years and three months in prison. He is serving his term in a federal prison in San Antonio.

The thefts alone caused more than $1.5 million in losses to the United States, according to the plea agreement that Charboneau eventually signed on Sept. 5, 2013. Her attorney, Hartley, told the court that her crime had also humiliated her husband, whose own Army unit had learned about it.

Charboneau said she is now haunted by how “I was so proud to be in the military, [and then] doing what I did.” After seven years as a soldier, trained to respect and trust her supervisors completely, she said, it was “really hard” to find out that a superior was engaging in theft.

Photo by Lucas Jackson/Reuters

Her advice to young troops deploying to Afghanistan today would be to “keep to themselves, learn the job that they need to learn,” and if confronted with a proposal similar to the one Hightower laid at her feet, just say no. “It wasn’t worth the forty-some-odd thousand dollars I made to be in prison for seven years, to be away from my … family,” she said.

Charboneau started serving her sentence in February, after a court-approved delay of five-and-a-half months, so she could briefly take care of her third child, Tate, who was born in July; all three of her children are now being looked after by her mother. In an email to the Center for Public Integrity, Charboneau wrote that she was adjusting all right to prison but missed her kids, especially her newborn. “[I]’m afraid most days he will forget me,” she wrote.

A tangle of emotions and crime

Court filings in more than 100 cases reviewed by the Center for Public Integrity show that many of the military personnel who wound up being convicted had earlier received honors and awards, and were well-regarded by their uniformed colleagues. Charboneau, for instance, won two medals for her service in the Fenty operations office. She received the first just months before she began stealing fuel with Hightower and Weaver.

So what makes such military personnel turn to crime?

The inspectors general for both war zones said criminal actions were provoked partly by the high volume of cash and resources flowing into the countries. “The more money you throw into a weak-rule-of-law situation, the more fraud you’ll see,” said Bowen.

Even by the diminished standards of 21st-century warfare, the conclusion of combat operations in Afghanistan feels awfully anticlimactic.

Todd Conormon, a lawyer who served in Iraq in 2004 and now defends service members accused of wrongdoing, said that for some, the sheer pressure of combat “has a debilitating effect, and maybe makes it easier … to rationalize, ‘Well, I deserve this.’ ” Others grew used to seeing corruption all around them—like the widespread financial impropriety Sopko described—and convinced themselves that a little more wouldn’t interfere with the essential goals of the U.S. mission, Conormon said. For some, the urge to steal was wrapped up in other temptations, such as an illicit romance with another service member, according to court documents.

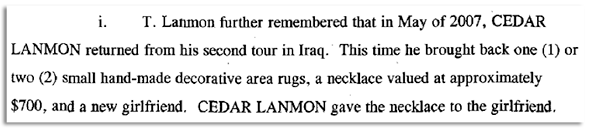

An Army captain from Tacoma, Washington, named Cedar Lanmon, who served in Iraq on two deployments from 2004 to 2007, accepted gifts worth tens of thousands of dollars in exchange for helping the Albanian owner of a company called “Just in Time Contracting” obtain a $250,000 contract from the U.S. military, according to a complaint filed against him on Nov. 15, 2007, by U.S. Army Criminal Investigative Division Special Agent Derek Lindbom. He wound up getting caught after his estranged wife—referred to by her first initial T in the complaint — called Lindbom’s agency to describe her husband’s misdeeds, financial and marital:

After Lanmon proposed that his wife join him and the new girlfriend in a “polygamous marriage,” according to the document, the couple “became estranged as husband and wife.” Lanmon served one year in federal prison and was released on Sept. 11, 2009. A Washington state phone number under his name had been disconnected when the Center for Public Integrity tried to reach him.

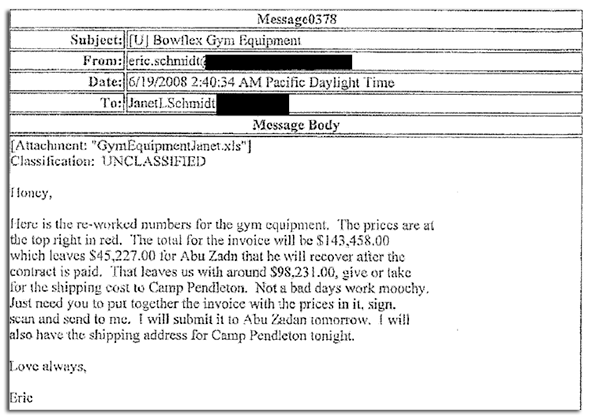

Other fraud schemes in Iraq and Afghanistan occurred with the full knowledge—and sometimes the complicity—of the service member’s spouse. U.S. Marine Corps Capt. Eric Schmidt and his wife, Janet, engaged in theft and contract fraud during his deployment as a contracting officer at Camp Fallujah in Iraq in 2008 and 2009. They netted a total of $1.69 million, according to the sentencing memo that Assistant U.S. Attorney Dorothy McLaughlin filed in the U.S. District Court for the Central District of California on Feb. 3, 2011.

They were an efficient team. Eric Schmidt helped Iraqis pilfer equipment from the base, such as generators and air conditioners, and steered military reconstruction contracts to one local firm in particular, according to the sentencing memo.

Janet Schmidt arranged for U.S. companies to supply smaller quantities or substandard versions of the equipment that the chosen Iraqi firm was supposed to be producing, the sentencing memo said. When the products arrived in Iraq, Eric signed a Defense Department form stating that the shipments had been sent by the Iraqi firm. The firm then sent the U.S. government a bill Janet had prepared, and when it was paid, the firm shared the proceeds with the Schmidts.

The scheme escaped notice during the year Eric Schmidt was deployed to Iraq, according to Daniel F. Willkens, a former head of investigations for Stuart Bowen. Schmidt even roped in two subordinate Marines to help him with the scheme, according to the sentencing memo. One of them, Staff Sgt. Eric Hamilton, received $124,000 from Schmidt and the Iraqi contractors for painting circles on generators in the military storage yard at Fallujah to show which ones they could take and then unlocking the gate when the contractors came to get them, according to charges filed in the U.S. District Court for South Carolina on July 27, 2011. Hamilton pleaded guilty to the charges on Aug. 10, 2011, according to his plea agreement.

Eric and Jane Schmidt were caught by chance. In 2009, five months after Eric Schmidt had returned to the United States and the couple had purchased costly property in California, Schmidt was arrested for assaulting his wife. While state police were inside the home, they noticed he had $10,000 in cash and that the bills were stamped with the imprint of an Iraqi bank.

Investigators from Bowen’s agency, the Pentagon, and the IRS were eventually able to confirm the money had come from Iraq and pieced together the rest of the story by examining the Schmidts’ financial transactions and correspondence. In the last report that Bowen’s agency submitted to Congress, in September 2013, the Schmidts’ case was described as the “biggest catch” of a special data mining team in his agency. In 2011, Eric Schmidt was sentenced to six years in prison while his wife was sentenced to one year of home confinement and two additional years of probation. The couple was ordered to pay the U.S. government $2.1 million in restitution, including income tax.

“Most of our cases were triggered by unexpected tips [revealed by] someone who had their conscience pricked and came forward,” said Bowen. Because the whistleblowers could be endangered by receiving public credit, they are rarely mentioned in court documents.

Sopko confirmed that most of the cases his agency successfully investigates come from tips, when service members call government corruption hotlines or when disgruntled representatives of military services companies come forward to complain that a rival seems to be getting all the prime contract awards. Charboneau’s scheme, for instance, was uncovered after Weaver talked about it with a sergeant with whom he was romantically involved, she said.

In Afghanistan, Sopko and his investigators typically use sources, undercover techniques, and firsthand testimony. Because recordkeeping in the country has been poor, he said, “we don’t just rely on paper.”

The contract fraud model

One exception was an elaborate contract-rigging scheme that culminated in the longest prison sentence given to any U.S. service member for fraud in Iraq or Afghanistan.

Photo by Jason Reed/Reuters

It began, according to court documents, as Army Maj. Eddie Pressley arrived at Camp Arifjan in Kuwait in October 2004 to work as a contracting specialist, ordering supplies for the base. Just before his arrival, he had received an Army Commendation Medal for exceptional service as a military recruiter.

His roommate at the base was another Army major, John Cockerham, who reviewed and awarded bids for Defense Department contracts to support the U.S. Army’s operations around the Middle East. By the time Pressley arrived, Cockerham had already been at the camp for three months—and had begun awarding contracts for goods such as bottled water in exchange for bribes, according to an indictment filed by a San Antonio grand jury against Cockerham on Aug. 22, 2007.

During a trial hearing on Dec. 12, 2009, Cockerham’s attorney, Jimmy Parks, said Cockerham agreed to participate in these schemes after a “lot of cajoling and convincing” by contractors, who told Cockerham that “our God requires that we bless you” for giving them “a chance to do business.” Assistant U.S. Attorney Mark Pletcher responded that the payments had not been blessings, “just bribes.”

A U.S. military presence could have mollified Sunnis and prevented the new civil war.

By March 2005, Pressley was likewise collecting bribes for awarding contracts and ordering extra goods under those contracts, according to the indictment that an Alabama grand jury filed against him on May 1, 2009. The men arranged for their wives to visit, collect the cash profits, and take the money home or send it to foreign bank accounts.

When an Army major and West Point graduate named James Momon arrived in the summer of 2005, Pressley and Cockerham took him for a ride in their jeep and described how their bribery scheme worked, according to descriptions of sealed testimony by Momon that federal prosecutor Peter Sprung and Pressley’s attorney, Clyde Riley, gave at February 2011 court hearings in Decatur, Alabama. According to Sprung, Momon said Cockerham and Pressley explained how they got the bribe money from the contractors, and how their wives and relatives helped move the illicit funds out of the country.

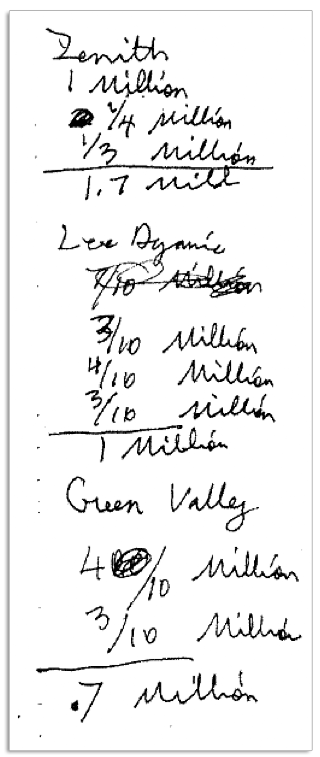

Court records and published reports by Bowen’s agency do not detail how the investigation began, but in late December 2006, federal agents executed a search warrant on Cockerham’s San Antonio home and discovered what they said was a highly incriminating ledger.

Cockerham had a compulsion to write down “everything from his dreams to the amounts of money he took,” according to Willkens. He neatly listed the names of contracting companies that paid him bribes, along with the values of the bribes he had already received and those he expected to receive. Of the $15 million he eventually hoped to receive in bribes, Pletcher told the court in the 2009 hearing, Cockerham had designated 10 percent to be used for building a church.

In total, Cockerham, Pressley, and Momon collected at least $14 million in bribes, according to court documents detailing the conduct of which they were convicted. Cockerham ended up receiving 17½ years in prison, the longest sentence given to any service member convicted of fraud in the two countries. At least seven other troops in Iraq and Kuwait were convicted of participating in the conspiracy. A military-veteran-turned-contractor who investigators say played a pivotal role in the case, George Lee, pleaded guilty in February to paying a bribe to one of the lieutenants and is now in a Philadelphia jail.

The conspiracy—and the suicide of an Army officer who killed herself in 2006 after confessing to federal agents that she had accepted at least $225,000 in bribes from Lee—has garnered wide attention.

The challenges of bringing a successful case in the middle of war

Sopko and others warn that the steady flow of military reconstruction funds into the two countries will not soon subside, with the deployment of 10,000 U.S. forces in Afghanistan recently extended to 2016 and new aid and military personnel starting to return to Iraq.

But auditors working for Sopko’s agency face increasing restrictions in Afghanistan. Military officials have told Sopko’s agency that they would only provide civilian investigators access to areas within a one-hour round trip of an advanced medical facility so that the U.S. government can provide them “adequate security and rapid emergency medical support,” according to a report Sopko’s agency issued in 2013. As a result, in 2014, Sopko’s investigators were only able to access one-fifth of the country.

Moreover, because the U.S. embassy in Kabul is shrinking, Sopko has been instructed to cut his staff there by 40 percent, to just 25 positions, by mid-2016. Everyone in Afghanistan, including his on-the-ground investigators, Sopko wrote in his agency’s report, will struggle over the next few years “to continue providing the direct U.S. civilian oversight that is needed in Afghanistan.”

Investigators say that even now, some service members whom they strongly suspect of fraud wind up getting away without prosecution because investigators simply cannot muster the evidence to bring them to trial, or because they prefer to go after large cases while letting smaller ones go.

In Iraq, recalled Willkens, he and his fellow investigators were sure they had uncovered the culprits behind certain lucrative crimes, but were equally sure they would not be able to prove it because the proceeds were stashed in inaccessible overseas accounts.

Bowen and Willkens also complained that stiff penalties were not assessed as often as they wished. “I suspected that many of these guys that we caught were perfectly happy to go to prison for a few years,” because they had much more money stashed overseas in places with little banking regulation, such as Cyprus or Jordan, Bowen said. “Prison was the cost of doing business for them.”

Other oversight officials confirmed that the amounts of money the U.S. government receives from service members convicted of fraud is rarely commensurate with their crimes. Restitution or forfeiture are set at whatever levels the judge decides is deserved, within the sentencing guidelines. In bribery schemes, for example, it is “often difficult to define specifically the loss to the government,” according to Peter Carr, a U.S. Justice Department spokesman.

Part of the challenge, according to Willkens, is that fraud is seen as a white-collar, nonviolent crime. If the service members who stole millions from the U.S. government had taken the same amount during an armed robbery of a bank, he said, they would receive much higher penalties.

“Robbing the government is seen as a victimless crime,” Willkens added. “It’s not.”

This story was published by the Center for Public Integrity, a nonprofit, nonpartisan investigative news organization in Washington.