The Big Gamble

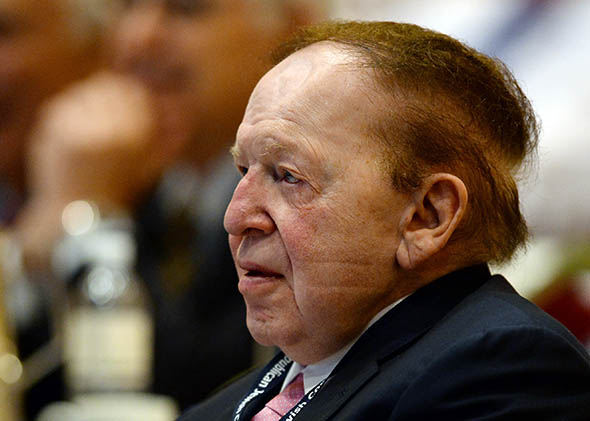

Casino king Sheldon Adelson wants to ban Internet gambling. But states are moving fast to legalize, and even the super PAC billionaire may not be able to stop them.

Photo by Ethan Miller/Getty Images

Ever since Bugsy Siegel opened the Flamingo Hotel in 1946 and launched the Las Vegas Strip, gambling has held a tenuous position in American life, suggesting glamour, wealth, and corruption all at once. Now that casinos have spread nationwide and allegedly shed their mafia ties, a new branch of the industry is fighting for legitimacy.

Las Vegas–based casinos and overseas operators have begun an all-out battle over Internet gambling, which is mostly banned nationwide but carries with it the promise of billions of dollars in additional revenue for casinos and state governments. Three states began licensing online betting last year, and Congress is facing increasing pressure to either bar or regulate the fledgling industry.

The moves are coming in response to a concerted push orchestrated by a colorful cast of characters, including Sheldon Adelson, one of the most prolific political donors of the super PAC era, an offshore company that only recently settled federal allegations of money laundering and bank fraud, and a pair of benignly named political advocacy groups backed by big-time casino cash.

Adelson, a prominent backer of conservative political causes and head of the Las Vegas Sands casino empire, has pledged to spend “whatever it takes” to get Congress to ban Internet gambling outright. In March, Sen. Lindsey Graham and Rep. Jason Chaffetz introduced a bill that was written with the help of Adelson’s lobbyists to achieve that goal.

Meanwhile, industry giants like Caesars Entertainment and MGM Resorts have taken the opposite tack, banding together in an effort to legalize and tap into the growing market. Maneuvering quietly in the background are foreign entities, including the Isle-of-Man-based PokerStars, the world’s biggest online poker operator. As a whole, the casino industry is among the most generous in giving to political candidates across the country. According to figures from the Center for Responsive Politics and the National Institute on Money in State Politics, the gambling industry contributed $287.6 million to state and federal campaigns from 2009 to 2012 (state data for 2013 aren’t yet available).

All together, these interest groups spent $8.2 million lobbying the federal government on Internet gambling last year, according to the trade publisher GamblingCompliance, and millions more in state capitals from Trenton to Sacramento. And while Washington has drawn much of the recent attention, the real action may come in the states. New Jersey, Nevada, and Delaware have already legalized online gambling, and lawmakers are debating the issue in seven other states right now.

In these capitals, the promise of gambling profits is mixing with a need to plug budget gaps. Lawmakers face pressure to boost revenues, while proponents of online gambling are dangling the issue as a pain-free “voluntary tax.” And so other states seem sure to follow—and there may be little that Sheldon Adelson or anyone else can do about that.

Original Sin

For years, online betting was neither forbidden nor permitted explicitly by state or federal laws. The Department of Justice had long argued that the 1961 Wire Act, passed to limit bookies’ use of interstate telegraphs, prohibited all forms of betting online. Others disagreed, arguing that the act applied only to sporting events. But with the issue unresolved, a handful of companies began offering gambling online to American players beginning in the late 1990s, operating out of loosely regulated offshore locales.

Online poker took a hit in 2011, though, when the Justice Department sued several of the biggest operators, including PokerStars. Prosecutors portrayed an elaborate scheme to deceive banks, which were barred from processing online gambling payments, saying executives had established fake online businesses with names like www.petfoodstore.biz to hide transactions worth billions. The companies eventually settled the suit without admitting guilt, but the day became known as Black Friday in the industry after it decimated the country’s online offerings.

Then later that same year, the department quietly reversed its opinion in response to an inquiry from the New York and Illinois lotteries, saying the Wire Act applied only to betting on sporting events. The opinion explained that the new interpretation was more consistent with the intent and language of both the Wire Act and a 2006 law that targeted illegal online gambling transactions. But some industry observers have questioned whether the decision, released on the Friday before Christmas, may also have been a political concession to the casinos and their powerful allies, including Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid. Either way, states suddenly could begin regulating online gambling within their borders.

The politically savvy online firms were ready. Some had hired their own lobbyists in D.C. years earlier. In 2005, a plucky young group called the Poker Players Alliance had appeared and quickly became the most prominent advocate for the online gambling cause, donating money to politicians, hiring former Sen. Alfonse D’Amato of New York, and testifying at hearings.

The alliance was formed as a “grassroots” advocacy group—and political contribution fund—by a handful of prominent poker players. But federal tax filings published by the website citizenaudit.org show that nearly all of its money in its first year came from $1.1 million given by Ruth Parasol and James Russell DeLeon, a married couple who started PartyGaming, one of the world’s largest online poker companies.

The couple, both native Californians, were living in Gibraltar at the time, and their company eventually entered into a “non-prosecution” agreement with the Justice Department in 2009, exchanging a $105 million fine and an admission that some of its past dealings had been “contrary to certain U.S. laws” for a pledge from the Justice Department not to prosecute the company. (PartyGaming had pulled out of the United States after Congress passed the 2006 Internet gambling transactions law.)

PartyGaming later merged with another company to become Bwin.party, which currently holds about 40 percent of New Jersey’s Internet gambling market in its partnership with the Borgata Hotel Casino and Spa, in Atlantic City.

John Shepherd, a spokesman for Bwin.party, said the company had some contact with the Poker Players Alliance prior to 2006, but that the couple gave their own money and that the company has never donated to the group. In October, Bwin.party announced that Parasol and DeLeon would divest their 14 percent stake as part of the company’s application for a license to operate in New Jersey.

But even if Bwin.party hasn’t supported the alliance, other online gambling companies have: the majority of its funds come from the industry, said John Pappas, the group’s executive director, including from PokerStars’ parent company, the Rational Group, which declined to comment for this article.

The alliance is particularly focused on countering Sheldon Adelson’s push to win a federal ban on online gambling. Adelson has been lobbying Congress through the Las Vegas Sands Corp. and has begun a broader campaign through a group he started last year called the Coalition to Stop Internet Gambling. When the coalition posted a message on its Facebook page showing an image of a child in front of a computer and warning of a “threat to kids,” the Poker Players Alliance urged members to fight back. When Adelson’s top political adviser testified that same month in front of a Congressional panel in support of a ban, Pappas was there too, arguing that millions of Americans are already gambling over the Internet, and that legalizing the practice would make it easier to protect those gamblers from criminal activity and addiction.

It’s all good theater that is suddenly attracting a lot of attention—but the battle between these heavyweights may result in a stalemate. Meanwhile, the states are moving ahead.

An American market

By some accounts, the push for legalizing online gambling through the states can be traced back to a 2009 meeting between New Jersey state senator Raymond Lesniak and lobbyist Joe Brennan Jr., who ran a Washington D.C.-based industry group called the Interactive Media Entertainment and Gaming Association, which represented online gambling companies. Lesniak had caught Brennan’s attention when he introduced a bill to legalize sports betting, but Brennan had another idea: Why not legalize gambling over the Internet?

In online betting, Lesniak saw hope for Atlantic City: a new form of gambling to draw younger clientele and help the state’s struggling casinos, which had been losing money for three straight years because of increasing competition in nearby states. Lesniak proved to be a dogged sponsor, and with help from a lobbying push by Princeton Public Affairs Group—one of New Jersey’s most influential lobbying firms, which was hired by Brennan’s group—was able to win passage of a bill in January 2011.

It took two more years, though, and the support of Caesars and the other casinos, before Gov. Chris Christie signed an amended version of the legislation. The casinos spent $1.2 million on lobbying in the state in 2012 and 2013, once they threw their support behind the measure. The offshore companies were active as well. The Interactive Gaming Council, a Vancouver-based industry association for online gambling companies, spent another $253,700, and PokerStars’ parent company, Rational Services, spent $204,353 last year.

Pappas met with Christie’s staff in January 2013, urging him to sign the bill, and the Poker Players Alliance rewarded the bill’s sponsors. The organization, Pappas, and four prominent poker players gave Lesniak’s campaign a total of $15,600 after the law passed last year, along with $2,000 to the Union County Democratic Committee, which contributed money to Lesniak’s campaign. The online gambling bill faced little opposition.

But the revenue from Internet gambling has so far proved disappointing. The casinos pulled in $27.2 million from late November, when the new websites began, through the end of February. At that rate, revenue will fall well short of the $200-$300 million analysts had forecast for the first year.

Even so, other states and casino firms still envision a potential bonanza. By the time Christie had signed the law, Nevada and Delaware had passed their own online gambling laws, with Nevada legalizing only poker. Several other states are looking at Internet gambling this year, including Massachusetts, California, Illinois, Iowa, Minnesota, and Mississippi, where a bill was introduced but failed to pass. Lawmakers in Louisiana have held hearings.

One issue is driving the debate in these states: Can Internet casinos generate new revenue to help close widening budget gaps? Nowhere is that question more pressing than in Pennsylvania.

Keystone Cash

Pennsylvania’s ornate state capitol sits high on a hill overlooking Harrisburg and the Susquehanna River. The building dates back to a more prosperous time in the Keystone State’s history, when wealthy industrialists like Andrew Carnegie drove a growing industrial economy.

Today there are plenty of reasons to worry. Pennsylvania is facing a $1 billion deficit and the state’s profitable casino industry has stopped growing. Pennsylvania and neighboring states have increased the number of allowable forms of gambling, boosting competition. Last year was the first time that Pennsylvania’s casino revenue did not grow since gambling was legalized in 2004.

The state takes 55 percent of revenue from slots and 14 percent from table games. “It’s about revenue,” said state Sen. Kim Ward, who chairs the Community, Economic and Recreational Development Committee. “Because every year we’re in a budget squeeze.”

In December, the state Senate funded a study to look at updating its gambling regulations and allowing Internet gambling in an effort to boost revenue. The report is due by May 1, in time for this year’s budget debate. Rep. Tina Davis, a Democrat, had already introduced a bill to legalize online gambling last year. But Republicans control both chambers and are likely to write their own bill if they decide to move forward after the report comes out.

The state’s stake in the casinos’ revenue gives the industry a powerful tool to influence policy, said Barry Kauffman, executive director of Common Cause Pennsylvania. All told, various interest groups spent $7.4 million lobbying on gambling and wagering issues last year in Pennsylvania, with Adelson’s Las Vegas Sands spending nearly $234,000, the most of the big casinos. PokerStars spent $42,500 lobbying in Pennsylvania in 2013.

Unlike in New Jersey, however, there’s opposition in both parties to allowing online gambling, and Republicans in the House have introduced bills to ban it. Adelson runs a casino in the state, so he carries considerable weight.

In February, state Rep. Mario Scavello, a Republican, introduced a bill to create criminal penalties for gambling online. Adelson’s Coalition to Stop Internet Gambling quickly issued supportive statements, and the Poker Players Alliance called its members to action with the opposite goal, directing people to flood Scavello’s Facebook page with angry comments, which the representative later deleted.

But with New Jersey already in the game next door, some lawmakers appear determined to adopt online gambling, even if it doesn’t happen this year. “I do think at some point we will be moving forward with this,” Ward said.

The Battle Royale

Meanwhile, the Washington lobbying game is ramping up again, driven largely by Adelson’s new push to ban online gambling.

Adelson had already begun pressing for a ban through Las Vegas Sands, which spent $320,000 on lobbying in Washington last year. But his formation of the Coalition to Stop Internet Gambling signaled a new phase in the political influence game. The group hired former New York Gov. George Pataki, former Sen. Blanche Lincoln of Arkansas, and former Denver Mayor Wellington Webb as national co-chairmen, and kicked off a national media campaign to convince the public of the ills of online gambling.

In February, the group released its first television ad, which warns that “disreputable gaming interests are lobbying hard to spread Internet gambling throughout the country.” The group also secured signatures from 15 state attorneys general on a letter expressing their concern about online gambling and urging Congress to restore the Justice Department’s initial interpretation of the Wire Act; in March, Gov. Rick Perry of Texas and Gov. Nikki Haley of South Carolina sent their own letters in favor of a ban.

Meanwhile, Las Vegas Sands lobbyists were reportedly circulating draft legislation to achieve this goal, a copy of which was published in January by poker blogger Marco Valerio. In late March, the campaign scored a major victory with the Graham-Chaffetz bill to ban online gambling. M.J. Henshaw, a spokeswoman for Chaffetz, said the Congressman wants the issue decided by lawmakers, not a Justice Department lawyer. Asked whether the bill originated with Adelson’s lobbyists, Henshaw said, “like any issue that my boss takes on, he seeks the advice of industry folks.”

Adelson and his wife and daughter contributed $15,600 to the Graham’s campaign account last year, and a Sands PAC gave another $5,000, according to the Center for Responsive Politics. The senator’s office did not respond to requests for comment, but Graham told NPR that his Baptist constituents and Adelson “are one with this,” and that, “this is really easy politics for me back in South Carolina.”

Chaffetz has not received contributions from Adelson, according to the Sunlight Foundation.

Neither Las Vegas Sands nor the coalition responded to requests for interviews, but in January, the Sands’ vice president for government relations, Andrew Abboud, told Nevada political reporter Jon Ralston that Adelson was “prepared to mount full campaigns in every state where a bill is introduced,” adding, “we are going to make it ‘the plague.’ ”

Adelson, 80, says he is morally opposed to the practice. He warns of a rash of underage gamblers betting in their living rooms and of the ease with which criminals and terrorists could rig games to launder money.

In a recent interview with Politico Magazine, however, Adelson admitted that beyond the moral argument, he fears for his industry, warning that if online gambling is legalized, software giants like Google or Facebook will take over the market, “and that’s going to be the end of all of it.”

Most of the rest of the casino industry disagrees, and the American Gaming Association, of which Sands is a member, announced in January that it was prepared to fight back. The group added new staff members and hired Jim Messina, who led President Obama’s 2012 reelection campaign, to help with “grassroots initiatives,” including online gambling.

The following month, the gaming association and other interests formed the Coalition for Consumer and Online Protection, which has hired former Reps. Michael Oxley and Mary Bono and launched a $250,000 ad campaign to block a federal ban. The coalition says it’s a matter of states’ rights, consumer protection, and Internet freedom.

In February, Nevada Sen. Dean Heller said he is preparing a bill to legalize Internet poker but ban other types of online gambling—a move he and fellow Nevada Sen. Harry Reid have previously pushed—telling the Las Vegas Review-Journal that “Adelson brings up some reasonable concerns.”

Adelson and his wife have given $18,800 to Heller’s campaigns since 2006, and other Sands employees have given another $27,550. Over the same period, the casino industry as a whole has given Heller nearly $640,000. The Adelsons have not contributed to Reid’s campaigns since 1995, but he has received $423,022 from casinos since 2009, according to the Center for Responsive Politics.

But the chances of passing such a federal bill will become more difficult as more states legalize their own systems of Internet gambling. To many, there’s a sense of inevitability to online gambling. I. Nelson Rose, a gambling expert at Whittier Law School, said that politicians have become inured to the reservations they once had about gambling, as state after state has legalized casinos. “Adding one more form, like Internet poker, is not a big deal now,” he said. “Every state has entrenched political operatives who have no problem with Internet gambling. As long as they’re the ones to run it.”

Ben Wieder contributed to this report.

This story was published by The Center for Public Integrity, a nonprofit, independent investigative

news outlet. For more of its stories on this topic go to publicintegrity.org.