Lincoln Had One. So Did Uncle Sam.

Why don’t politicians today grow beards?

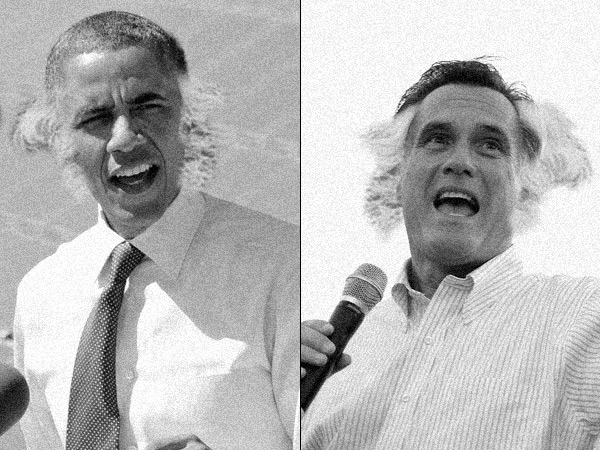

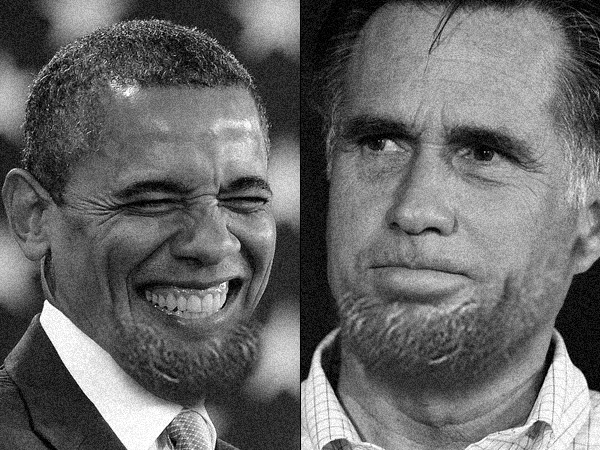

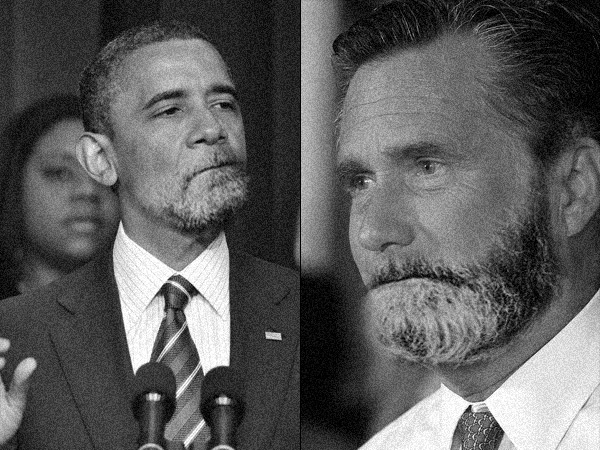

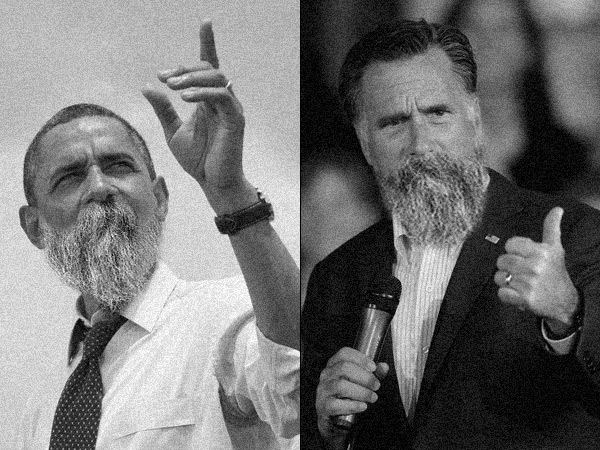

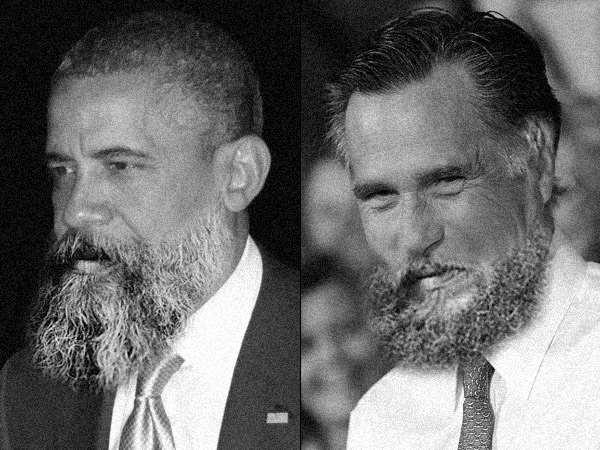

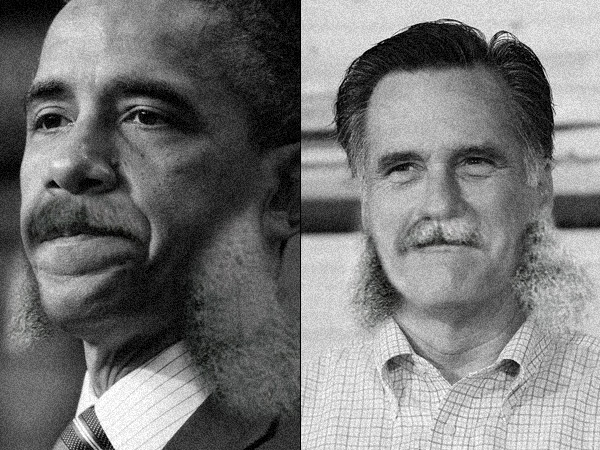

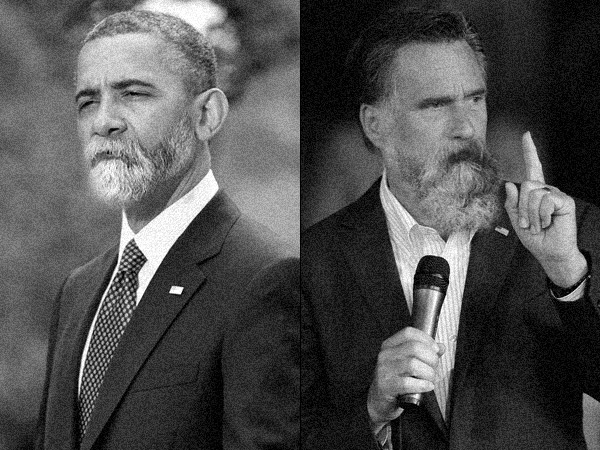

Though the gentlemen who vied for the Republican presidential nomination disagreed on many things, from tax policy to contraception to the feasibility of establishing a colony on the moon, there's one critical issue on which they were firmly in accord: facial hair. This was true of the eventual nominees in the last election, and the one before that, and in every other presidential contest going back to 1916. One hundred years ago, two of the four men running for president were proudly hirsute, as were two of the four vice-presidential candidates. Today, the sitting president can't grow whiskers and his challengers wouldn't dare try. When did the beard lose its political prestige?

In his delightful 1930 monograph Concerning Beards, Edwin Valentine Mitchell notes that "the fortunes of the beard have always fluctuated through the ages. It flourishes for a time in full splendor, then diminishes in size, and finally disappears altogether, only to burst forth once more in all its former glory." In much of the premodern era, a healthy beard connoted influence and high status; Mitchell says that "one ancient king actually made a terrible scene because the reigning head of another state sent a beardless youth upon a political errand to his court." The opposite is true, too: Men pressed into servitude were often shorn of their beards as a sign of subjugation.

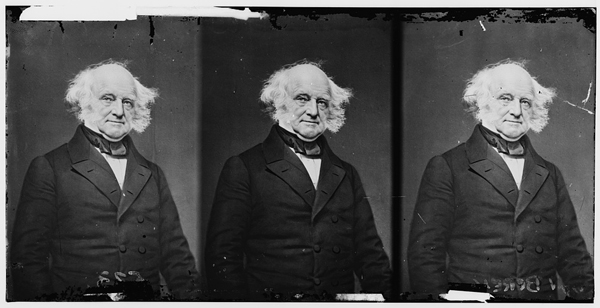

By the time of the Revolutionary War, facial hair had gone out of style in America, explains Victoria Sherrow in her Encyclopedia of Hair: A Cultural History. And, indeed, the first 15 U.S. presidents were beardless, though John Quincy Adams did sport a rather nice pair of muttonchops. A sign of the times: In 1830, a man named Joseph Palmer was jailed for a year in Fitchburg, Mass., after fending off four men who attempted to forcibly rid him of his widely loathed beard. (Palmer's gravesite is marked with a monument that reads "Persecuted for Wearing the Beard.”)

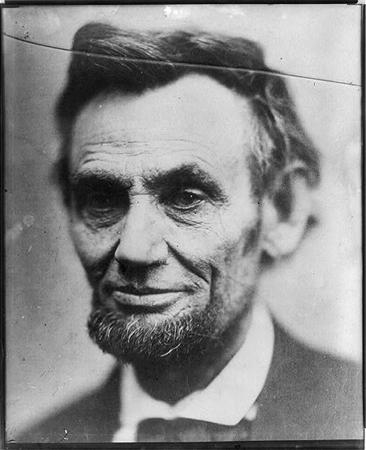

In the mid-1800s, whiskers made a comeback in American political life—or, as Reginald Reynolds put it in his odd 1950 volume, Beards, "a beard was becoming almost as necessary as a Bible to a rising demagogue." Abraham Lincoln began his presidency as a baby-faced rube from rural Illinois, governing a country on the brink of collapse. After growing a beard at the behest of a schoolgirl, he vanquished the South and passed into legend.

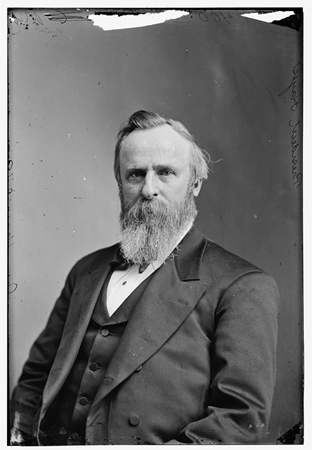

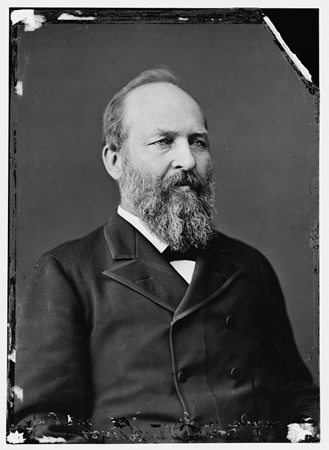

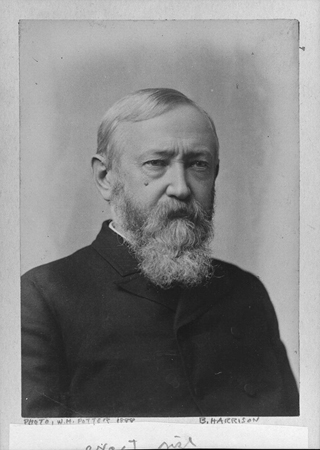

Every subsequent president up to William Howard Taft wore some sort of facial hair, except for Andrew Johnson, who was impeached, and William McKinley, who was assassinated. If you wanted the Republican Party's nomination, a beard was as necessary then as a Reagan fetish is now.

That changed in the early 1900s, likely due to the advent of the Gillette safety razor, which debuted in 1903 and eased the performance of what had long been a hated and bloody chore. Soon thereafter, the military banned beards, as they interfered with the seal on gas masks. By 1930, Edwin Valentine Mitchell would write that, "In this regimented age the simple possession of a beard is enough to mark as curious any young man who has the courage to grow one."

In politics, that's been the case ever since. No sitting president has worn facial hair since Taft. Charles Evans Hughes was the last bearded major-party presidential nominee; he lost to Woodrow Wilson in 1916. Today, it’s received wisdom that candidates should be clean-shaven. “Except for a brief window from Sept. 11 to 2003-2004, most of the last 15 years in politics have been about change, and a wizened graybeard doesn’t really convey change,” says Jeff Jacobs, creative director and founder of NextGen Persuasion, a campaign consultancy firm. “In 500 campaigns I’ve almost never had a conversation with a candidate about whether or not to have facial hair,” explains Democratic media consultant John Rowley. “It’s almost like conventional wisdom about facial hair has already hit candidates before they even run.”

The beard’s absence from modern American politics can be partially blamed on the two scourges of the 20th century: Communists and hippies. For many years, wearing a full beard marked you as the sort of fellow who had Das Kapital stashed somewhere on his person. In the 1960s, the more-or-less concurrent rise of Fidel Castro in Cuba and student radicals at home reinforced the stereotype of beard-wearers as America-hating no-goodniks. The stigma persists to this day: No candidate wants to risk alienating elderly voters with a gratuitous resemblance to Wavy Gravy.

A few politicians have managed to win elective office in spite of their hairy visages. Moderate, beard-having Ohio Republican Steve LaTourette has been a House stalwart since 1995. Who liked Rep. David Obey's beard? The voters of Wisconsin's seventh district did: They elected its wearer to 21 consecutive terms before Obey retired in 2011. Sen. Tom Coburn sometimes wears a beard, and its occasional appearance is eagerly awaited by Hill types. Coburn's beard even has its own tribute Twitter account, which boots up whenever the senator's whiskers begin to sprout. (Sample tweet: "i've asked tom to spend a few minutes combing me before tonight's #SOTU, i must maintain my supple virility.")

But mostly, a list of contemporary bearded politicos is a roster of the inept and inessential. There’s former New Jersey governor Jon Corzine, who’s currently embroiled in a massive financial scandal. Florida Rep. Alcee Hastings was impeached and removed from office while serving as a federal judge in the 1980s. Ex-New York governor David Paterson’s three-year tenure did much to improve the fortunes of Saturday Night Live. Cantankerous Alaska congressman Don Young, known as “Mr. Pork,” has seemingly been ostracized from the beard community. ("Young is kind of a disgrace to beards around the world," wrote one member of a beard-centric message board). The oddly bearded jurist Robert Bork is the only person in the last 40 years to have his Supreme Court nomination rejected by the Senate. Ben Bernanke is the first beard-wearer to chair the Federal Reserve; he is currently one of the most-loathed men in America.

Sometimes, a beard makes it seem like a politician is either emerging from or embarking on a three-day Smirnoff bender. “A lot of times people associate beards with what happens after you lose a campaign and you let yourself go,” says Jacobs. Indeed, one need only picture a dazed, broken Al Gore circa 2001, puffy and bearded like a white-collar woodsman gone to seed, to understand why politicos identify facial hair with failure and shame. There are other negative connotations, too. "One misperception is that somebody who has a beard is lazy and can't be bothered to shave, sort of on par with somebody who's too lazy to brush his teeth," says Phil Olsen, the founder and self-appointed captain of Beard Team USA, who would know. "Some people perceive beards as disrespectful."

When I asked John Rowley if he could think of a circumstance when he might actually advise a candidate to grow facial hair, he paused for a few seconds. “Maybe when people have a lot of scars on their face from an accident,” he finally answered.

Barring a surge in the number of disfigured men running for office, voters shouldn’t expect the political beard to re-emerge anytime soon. Because the real reason most candidates don't have beards is because most men don't have beards, and there’s nothing to be gained by deviating from the mainstream. “Candidates get criticized mercilessly on what their appearance is, so they go to great lengths to get a political uniform down that isn't too distracting,” says Rowley. Which makes sense: The last thing a candidate wants is for his crazy beard to distract from his sober, rational message about living on the moon.

And yet, though beards might not be all that common, they’re actually well received among the general population. "I do a lot of work with visual communications, facial expressions, how people read faces," says Jeff Jacobs. "Facial hair poses no distraction or causes no aversions whatsoever." Academic research bears this out: In a 1990 paper for the journal Social Behavior and Personality, J. Ann Reed and Elizabeth M. Blunk reported "consistently more positive perceptions of social/physical attractiveness, personality, competency, and composure for men with facial hair." More recently, researchers Barnaby J, Dixson and Paul L. Vasey rejected the notion that "facial hair decreases a male's perceived social status because it is associated with traits such as vagrancy." In fact, participants in their study "rated bearded men as having higher social status than clean-shaven men."

Are there any politicians whose campaigns might have been helped if they had worn beards? “You put John Kerry in the room with a well-groomed beard, and it makes it a lot harder for that flip-flopper charge to stick,” says Jacobs. “He seems like a guy who changes his positions because they evolve, and because he thinks about things.” Former New Mexico governor Bill Richardson ran for the Democratic presidential nomination in 2008, only to drop out after getting no traction in Iowa and New Hampshire. Soon thereafter, he grew a beard; if he had had one during the primaries, voters might not have been scared off by his hideous double chin. And despite his name, Jon Huntsman struck this year's Republican primary voters as the sort of person who might faint in terror if invited pheasant-shooting. A beard might have lent his campaign a solidity that it so desperately lacked.

Beards won’t take hold in politics, it seems, until a bearded candidate wins a high-profile election. Politicians are unabashed copycats and generally won’t try a new campaign strategy until it’s been proven to work. Howard Dean’s successful use of online organizing in the 2004 presidential primaries paved the way for every digital campaign tactic in use today. Bill Clinton’s smooth jazz stylings in 1992 led directly to the “Saxophone Congress” of 1994.

Though the prospective 2016 presidential candidates are, thus far, a beardless lot, there’s still plenty of time to establish an exploratory committee for someone like Beard Team USA captain Phil Olsen, who is perhaps the best hope for the future of American political beards. “We love America, and we’re growing beards for America,” Olsen says of himself and his teammates. Someone’s got to.