Ed Graf was a bad employee. While working at Community Bank in Texas in the 1980s, he allegedly embezzled from his employer, eventually paying the bank more than $75,000 to avoid prosecution.

Ed Graf was a bad husband. His ex-wife, Clare, would call him “the most possessive person I’ve ever known.” Clare’s best friend, Carol Schafer, said her husband, Earl, saw Graf having sex with another woman the night of Graf’s bachelor party.

Ed Graf was, according to Clare and her family, a bad father. Two of Clare’s family members accused him of beating his adopted stepsons, Joby and Jason, with a board and belt.

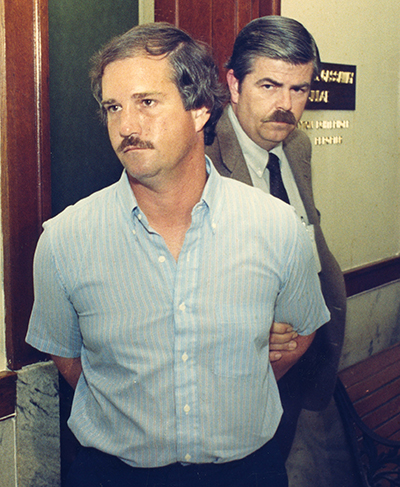

In 1988, a Texas jury found that Ed Graf was also a murderer. Prosecutors argued that two years earlier, on Aug. 26, 1986, Graf had knocked out Joby, 9, and Jason, 8, and placed the boys in the back of their family shed. Graf had then spread gasoline, locked the shed, and set the boys ablaze.

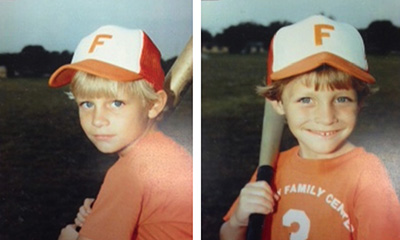

The two inseparable, athletic, blond-haired brothers died of smoke inhalation and severe burns in the backyard of their home. The address was 505 Angel Fire Drive.

Trial evidence photo presented by the state of Texas

On the day of the fire, Graf broke the news to his wife, telling Clare that both boys had been lost in the blaze. But Graf had been informed that the body of one child had been found, not both. It was one of many pieces of circumstantial evidence that prosecutors would pile up to present Graf as a calculating, greedy, and callous monster who murdered the children in a desperate attempt to keep his troubled marriage together.

Other small clues seemed to point to Graf’s guilt. Multiple witnesses say they saw a gasoline container on the porch, not far from the kids’ bikes. Graf also acted strangely after the fire. He suggested the boys be buried in one coffin, according to multiple witnesses. He didn’t offer his wife consolation, or apologize that they died in his care. A few weeks after the fire, Graf returned about $50 worth of Joby and Jason’s new school clothes that he had previously insisted they keep the tags on. There was more of what others saw as signs of foreknowledge. The normally meticulous Graf, who was said to keep lists for everything, neglected to buy the boys’ cereal or fill Jason’s Dimetapp prescription the week of their deaths.

In addition to the circumstantial evidence, prosecutors were able to present motive. Weeks before the fire, Graf had taken out $100,000 worth of combined life insurance on the boys if they were to die in an accident. The policies had been mailed out the day before the fire.

The real motive, prosecutors argued, was to get the boys—a source of regular bickering between Graf and his wife—out of their lives. His wife testified that shortly before the fire, she had threatened to leave him over his strict discipline of Joby and Jason, sons from a previous marriage, and to take their newborn third son, Edward III, with her.

The case was still largely circumstantial, though. The thing that likely clinched Graf’s conviction was the scientific testimony of a pair of forensic examiners. Joseph Porter, an investigator with the State Fire Marshal’s Office, testified that, based on his analysis of photos of the remains of the scene, the door of the shed must have been locked from the outside at the time of the fire, which would indicate foul play. He also said there were obvious charring patterns on the floor of the shed left by an accelerant. “The fire was definitely incendiary,” Porter declared. The prosecution’s other expert, a top fire investigator from New York known for his report on the Osage Avenue fire, a notorious fire set by Philadelphia officials that destroyed a primarily black neighborhood, was brought in to testify that there was “no doubt” that this was arson.

If the fire was intentionally set, then Graf was the only suspect with means, motives, and opportunity. Even if there was no direct evidence connecting him to the crime, the circumstantial evidence and the word of two arson experts was enough. The jury deliberated for four hours before pronouncing him guilty of capital murder.

The jurors then had to decide the punishment. The district attorney, Vic Feazell, said that the “facts of the case cry out” for the death penalty—two boys burned alive, murdered by a trusted parent.

Defense attorney Charles McDonald gave an impassioned plea that the jurors had convicted an innocent man and would make the injustice irreversible if they chose execution over life in prison. “I’m asking for this man’s life because if you did make a mistake there’s going to be some folks, somewhere down the line, it may be years … but maybe the mistake can be corrected,” McDonald argued. “If you take this man’s life, there ain’t no way to ever correct it.”

The jurors must have found this argument compelling, because they spared Ed Graf’s life.

Twenty-five years later, the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals decided that a mistake had, in fact, been made. The investigators who testified the fire was arson used what in the years since has been discredited as junk science. A state review panel set up to examine bad forensic science in arson cases said that the evidence did not point to an incendiary fire. A top fire scientist in the field went one step further: The way the boys had died, from carbon monoxide inhalation rather than burns, proved the fire couldn’t have been set by Graf spreading an accelerant, and was thus likely accidental. The defense’s theory was that the boys, who multiple witnesses said had a history of playing with matches and cigarettes, had set the fire themselves, attempted to put it out, and been quickly overcome by carbon monoxide poisoning.

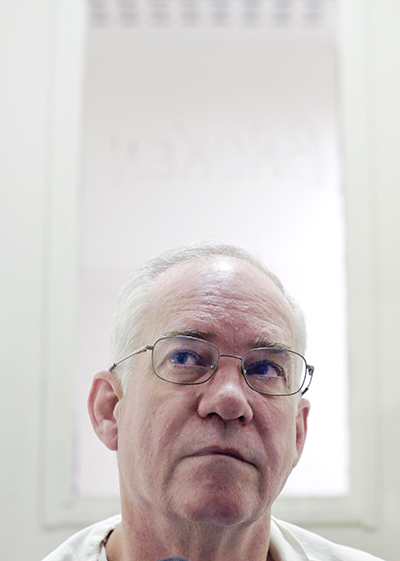

Photo courtesy of the Todd Willingham family

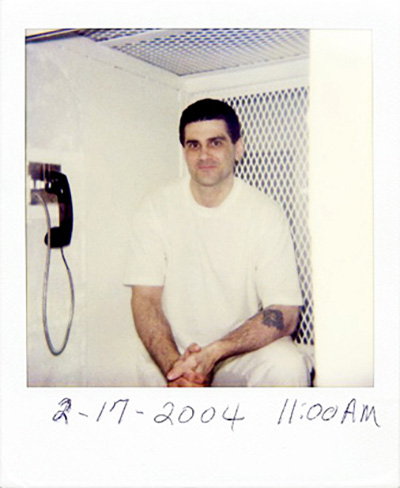

The reason Ed Graf’s case was reviewed a quarter of a century after he barely escaped the death chamber was because of one man: Cameron Todd Willingham. He was convicted, based on similarly faulty scientific evidence and the testimony of a jailhouse informant who later recanted and said he was bribed, of murdering his three children by setting their home on fire two days before Christmas in 1991. Willingham was executed 11 years ago. Only after Willingham’s death was it revealed publicly that the forensic evidence used to convict him was bunk. In 2009, the New Yorker’s David Grann wrote a groundbreaking article describing Texas’ flawed case against Willingham. The story sparked a national uproar over forensic science and the death penalty.

Then Texas did something surprising. While the state has not budged in its use of the death penalty—just last year topping 500 executions since the state brought back capital punishment in 1982—it has reinvented itself as a leader in arson science and investigation. A new fire marshal, Chris Connealy, revamped the state’s training and investigative standards. He also set up a panel comprised of some of the top fire scientists in the country to reconsider old cases that had been improperly handled by the original investigators.

Graf’s case was one of the first up for review, and it was determined that the original investigators had made critical mistakes. The Texas Court of Criminal Appeals agreed, overturning the original conviction.

Graf’s successful appeal proved that Texas was serious about correcting past forensic errors, but his story was far from over. Prosecutors in Waco were not convinced of his innocence. They felt that they had enough evidence to reconvict. Just because the forensic science was flawed didn’t change the fact that, in the eyes of prosecutors, Ed Graf was a bad employee, a bad husband, and a bad father—a man capable of murdering his adopted children.

So there was a new trial, and Graf became the first man in Texas to be retried for an arson murder that had been overturned thanks to advances in fire science. His new trial set up a clash between modern forensics and the old way of pursuing criminal justice in Texas, a state where prosecutors have often gone to questionable lengths to win convictions against high profile murder defendants—including multiple men later proved innocent.

Prosecutors in Graf’s retrial spared no effort to win a second conviction in a strange and dramatic retrial last October. The trial’s surreal and unforeseeable conclusion would have a profound impact not just on the fate of Ed Graf, but on the lives of other prisoners who in the wake of the Willingham case held out new hope that their convictions might be overturned and their innocence acknowledged.

When T.J. Clinch first took the witness stand for Ed Graf’s defense, back in 1988, he had been a nervous 10-year-old. A couple of months before Joby and Jason died, the brothers had been playing at Clinch’s house when they found some matches and lit a cup of grass on fire. Clinch got scared, and they quickly blew it out. Defense attorneys used Clinch’s testimony, and that of multiple other witnesses, to portray the two boys as having a fascination with fire. When Jason and Joby’s mother, whose name is now Clare Bradburn, remembers what was said about her children, it angers her.

“It’s hard to sit there and listen to things that you know are not true,” she told me as her ex-husband awaited his new trial. She didn’t believe what the neighbors and teachers were saying about her kids. “It’s very hard to hear somebody saying ugly things and trying to make your children sound like they’re little heathens,” she said. “They were just kids. They were just little boys.”

Twenty-six years later, on Oct. 7, 2014, Clinch was called back to Waco’s 54th District courtroom, this time to testify for the prosecution. He had become a thin, serious-looking 37-year-old real estate agent. His facial features were boyish, and when he got up to talk about his childhood friends, Clinch seemed to revert back to that small, nervous kid.

“The story of them being this bad person, playing with fire all the time—there was one instance we played with matches, or fire,” he said. “They wouldn’t have been playing in that shed,” Clinch added, before breaking down in tears.

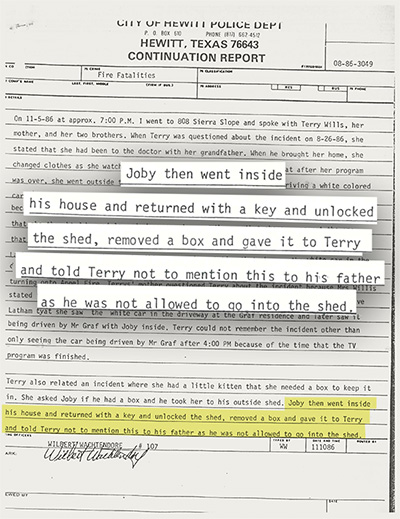

One person had said she’d seen one of the brothers go into the shed, though, only four or five days before the fire. In November 1986, 9-year-old Teri Wills told a detective that Joby had taken her to the shed the week before the fire, and that he even knew where the key to the shed was kept. Joby had, according to Teri, told her not to mention it to his father because he wasn’t allowed in there.

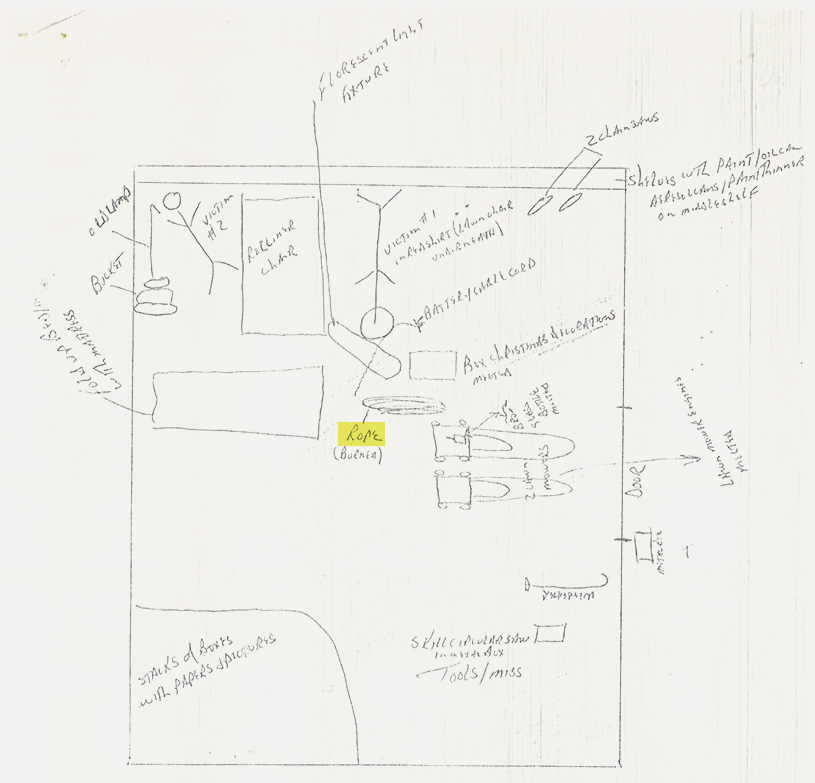

Graphic by Lisa Larson-Walker. Document via City of Hewitt Police Department.

In 2014, Teri, whose last name is now Rinewalt, was testifying against Graf. She said that she didn’t remember Joby ever bringing her to the shed. She remembered something else, though. She remembered going to the Grafs’ home the day of the fire, knocking on the door for the boys to come out and play, and no one answering. Prosecutors would argue that Graf was too busy killing his stepsons at the time to answer the door.

In 1986, the police didn’t record anything about Teri mentioning that no one answered the door to the Graf residence. When she and T.J. spoke to investigators the day of the fire, they both said they had been playing with the two boys earlier in the afternoon, according to a police report. A few weeks after the fire, police reported that “neither [Teri], nor T.J. Clinch, or any of the other regular playmates of Jason and Joby Graf had been over at the Graf house the day of the fire.” When I spoke with Rinewalt after her testimony, she told me she is certain of her memory of going to the door, because she remembers feeling guilt as a child that she could have done more to save her friends. “I can physically remember walking up the steps to their front door,” she said to me.

Clinch and Rinewalt were among a number of critical witnesses who would come forward with damning new testimony that hadn’t been shared in the 28 prior years. This new testimony would be emotionally powerful, form the basis for much of the prosecution, and—for the most part—prove very difficult to verify. Even in the best of circumstances, eyewitness testimony is notoriously unreliable; at Graf’s second trial, the testimony was offered 28 years after the fact, and multiple key witnesses had been young children at the time of the alleged crime.

Rinewalt acknowledges that there are things that she’s forgotten over the years. “Could there have been a time that I did [go to the shed] and it just wasn’t a big enough deal for me to remember it now? Maybe, but I don’t have any recollection of ever really playing in their backyard,” she told me. “I feel like if I had spent time in that shed, I would have remembered that.”

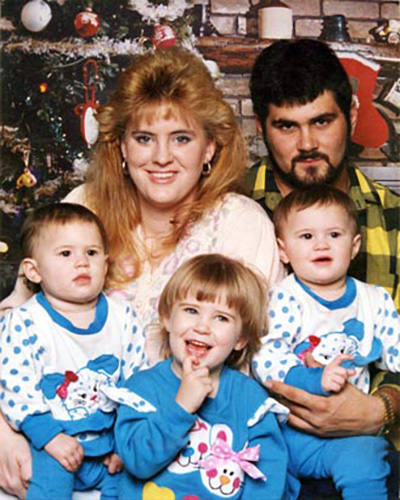

As Rinewalt testified in between sobs about her best friend “Frog Legs”—her nickname for Jason—prosecutors showed photos of Joby and Jason posing in their soccer uniforms, socks pulled over their knees and wearing goofy grins. There was also a photo of the two boys in tuxes at their aunt’s wedding, an image that had been blown up and displayed between their caskets at their funeral. Family testified at both trials that Graf was so cheap that he had not wanted to pay to have it enlarged. The photo hung over their mother’s mantel for years, and lead prosecutor Michael Jarrett kept it in his office during the trial, he told me, to remind him what he was fighting for.

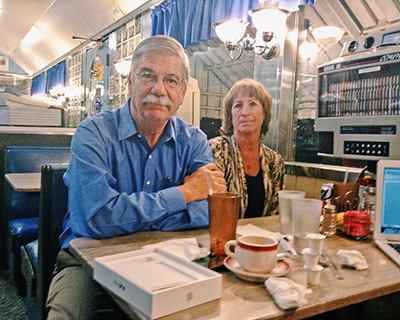

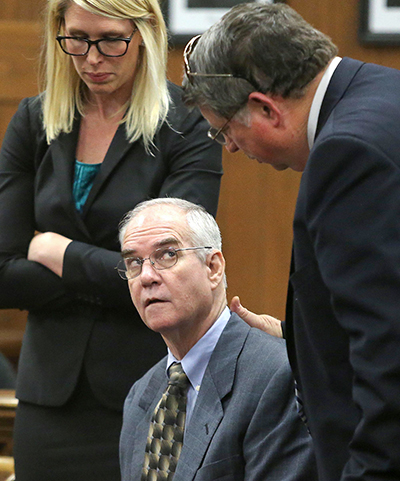

Photo by Jeremy Stahl

Another early witness who would set the tenor for the trial by coming forward with new information was Jason and Joby’s cousin. Jenny Lilly was 6 at the time of the fire and hadn’t testified in the first trial. But she now told jurors that Graf had beaten her cousins with a belt 10 to 15 times in a single sitting for not taking a nap. To add to his cruelty, Graf had made the little girl watch. Lilly hadn’t told anyone, not even her mother, about the beating until a month before Graf’s new trial.

It was difficult for Graf’s defense team to counteract the emotional power of his accusers. Although a string of witnesses testified that Graf was a loving, devoted father and a good man, their accounts had less resonance than the prosecutors’ gut-wrenching story of two little boys stolen from their family and friends. Defense attorneys promised a dry case built almost exclusively on science. Graf’s lead attorney Walter Reaves told me over the phone that he chose this science-focused strategy because it was the “most viable one” and the “one that was supported by the evidence and the experts,” in addition to being the strategy that got Graf’s case reversed and sent back to trial in the first place. The downside of that choice was that, from the start of the trial, the defense was incredibly reliant on technical jargon to make its case. “Is it difficult to sell to juries?” Reaves told me. “It can be.”

The defense faced another significant hurdle: It couldn’t mention Graf’s previous trial, the 26 years he had spent in prison, or the fact that the original conviction had been overturned. The judge had ruled that such information might bias the jury. This decision led to bizarre scenarios in which witnesses were asked to compare their present-day statements to previous sworn testimony of unstated origins. Even more strangely, several now deceased or otherwise absent witnesses had their testimony reread for the court by lawyers acting as their ghostly embodiments. These witnesses tended to be for the defense, and their words were far less emotionally resonant than those of witnesses who appeared in person.

There was one exception to this pattern. Graf maintained an excruciating display of composure during the trial (he barely blinked when his own son, who had disowned him more than a decade earlier, testified against him). The only time he almost broke down was when a defense lawyer read the testimony of his mother, whose death and funeral he had missed while in prison. “He loved them very much. He was very good to those children. He played with them. He worked with them. He took them places,” the testimony went. “There is no way on God’s earth that he could have hurt those babies.” Graf rubbed his eyes and shifted his head.

Photo by Steve Earley/Waco Tribune Herald via AP Photo.

Graf did have one advantage at the start of the trial, however. Defense attorneys successfully argued that the accusation of embezzlement, for which Graf was never tried or convicted, was prejudicial character evidence, and therefore inadmissible. The logic of keeping this sort of evidence of past bad behavior out is simple: Just because Graf was an alleged embezzler, it didn’t mean he murdered his stepsons.

Still, the jury was allowed to hear that Graf owed the bank more than $75,000 in the year before the boys’ deaths. He paid it all back half a year before the fire with the help of his parents, but he had to cash in his pension to do so. These financial woes, along with his purchase of the universal life insurance shortly before the fire, combined to form the alleged motive.

Graf had his own explanation for the insurance. He claimed he had purchased it as a savings vehicle for all three of his kids. Graf had paid for his own college education using funds his parents had saved through an insurance plan. His brother and some of their family friends also claimed to have taken out insurance on their own kids, also as savings vehicles. On cross-examination, Clare Bradburn acknowledged that Graf had been talking about getting life insurance even before their youngest son was born, more than six months before the fire. The insurance letter that Graf and his wife were sent the day before the fire described the investment plainly: “[T]hese contracts make an excellent place to store cash. … I would suggest that you make this your first choice when thinking of saving dollars for the children.”

Was the shed door open or locked shut? That question has always been critical to whether or not Jason and Joby Graf were murdered. If the door was locked from the outside, then they had clearly been trapped. In 1988, the fire investigators testified that they had found indications that the door had been locked from the outside. That evidence has been found faulty by modern fire science. The new science used in Graf’s appeal and retrial was the result of a decades-long revolution in the field. The question Ed Graf’s case posed was whether that revolution would be enough to set a man free.

Photo by Jeremy Stahl

Gerald Hurst, the first arson scientist to discover the flaws in the Willingham conviction, issued a report in 2008 on the Graf case saying that the door was likely open at the time of the fire. Had it been closed, the fire probably would have been starved of oxygen.

“This should have been an undetermined fire,” Hurst told me months before Graf’s second trial (he died this past March). “There’s not any proof. Nothing.” A classification of undetermined means just that: You can’t identify whether the fire was intentionally ignited or an accident.

Hurst’s theory was that the boys were playing with matches and accidentally set on fire a fold-up bed stored in the shed. If the boys were in the back of the shed when such a fire was set, the fumes might have overwhelmed them too quickly for them to escape.

At Graf’s new trial, another fire science expert, Doug Carpenter, testified that the heightened levels of carbon monoxide in the boys’ blood indicated that they had passed out in the way Hurst described.

Carpenter spoke with me before the trial at the Maryland offices of his company Combustion Science & Engineering Inc. A gasoline fire, like the one prosecutors alleged Ed Graf started, would run out of air and die down sooner than a non-gasoline fire, he said. “But they’re both gonna die unless something changes in the ventilation.” Carpenter modeled the fire using a government simulation to show that the shed door was likely open.

The original investigators claimed that the fire started around the door because that was the area with the hottest burns. They reasoned this was where gasoline must have been poured. But when, a couple of weeks after the fire, chemists tested soil samples from the ground beneath the shed along with items from the shed and clothing from the children, the gas chromatograph found the presence of paint thinner (which had been stored in the shed), but no gasoline. Modern analysis shows that ventilation from an open door, not gasoline, would have explained the burn patterns around the door.

Carpenter told me he felt the case should never have been prosecuted. An important indicator for him that this was an accident was the high levels of carbon monoxide found in the boys’ blood. High carbon monoxide levels are associated with death by smoke inhalation, often far from the origin of a fire. People who die near a fire tend to succumb to thermal burns from the flames and stop breathing before they can inhale that much carbon monoxide. There were several items in the shed that could have caught fire and then released large amounts of carbon monoxide. Carpenter said the list includes an upholstered chair, a fold-up bed, a tire, or one of the shelves in the back of the shed.

Photo by Jeremy Stahl

These types of fires often befuddle investigators. “We’ve had fires where we’ve been brought in and the fire department goes, ‘We’ve got four people dead in this apartment, we’ve got soot everywhere, we’ve burned out a base cabinet near the stove, we don’t get it. How did these people die? They should’ve been able to walk out of this fire,’ ” Carpenter said. He showed me an example, which he presented during the Graf appeal hearing, of an Australian woman who died of smoke inhalation in a room that she should have easily been able to escape. The fire was located almost entirely under a knee-level nightstand.

“Most people would walk in and go, ‘How did this happen, for this small fire?’ ” Carpenter said. The answer is that the high levels of carbon monoxide incapacitate the victim. Depending on what materials are being burned, hydrogen cyanide could also be released, which would disorient and incapacitate a person even faster than carbon monoxide. The process could take a few minutes or less.

Hydrogen cyanide is more difficult to test for than carbon monoxide. It was not tested for in the autopsies of Joby and Jason Graf. Hydrogen cyanide release is typical, though, in smoldering fires involving furniture upholstered with polyurethane foam. “The highest number of fatal fires occur when a cigarette and upholstered furniture are involved,” Carpenter told me. There were at least two items in the shed—the fold-up bed and the reclining chair—that were likely to have been upholstered with polyurethane foam. If the boys had tried to put out a chair or mattress fire because they knew they would get in trouble for having started it, not to mention for being in the shed in the first place, then they might have quickly passed out.

By contrast, if the initial fuel for the fire had been gasoline, the boys would have had to inhale the fumes for at least 45 minutes, according to Carpenter’s analysis, to reach the levels of carbon monoxide found in their bodies. The fire was put out within 15 minutes of being discovered, and the boys were home from school for only 20 to 30 minutes before anyone noticed the fire. The only hypothesis that makes sense to Carpenter is that the fire released enough carbon monoxide or hydrogen cyanide to quickly knock the boys out and kill them.

He was convinced of this to a “reasonable degree of scientific certainty.” That’s as certain as he could be. “Science basically says ‘This is the best answer we can get,’ ” he said.

The justice system, however, likes definitive answers. Carpenter’s cautious self-skepticism—an ideal quality in a scientist—might read as wavering to a jury. After talking to him for three hours, I wasn’t 100 percent convinced of his hypothesis, which is based on new research that—although it has been peer-reviewed—isn’t yet widely accepted in the fire science community. The panel for the state of Texas that re-examined the case said that the original investigators had made mistakes and that the scene was too compromised to determine what the cause was, but that’s as far as it would go.

Carpenter’s cautiousness wasn’t the only problem for Graf’s defense team. His use of technical terms such as flashover, artificial stratification, burn bag velocity, stoichiometric points, and radiant energy revealed an impressive degree of knowledge. But these terms would be incomprehensible for a lot of jurors.

“Is a jury gonna be able to go back to the room and summarize what I said? The likelihood of that is pretty nil,” Carpenter admitted. “So that’s why the outcomes of these juries sometimes are such that they’ll be like, ‘I don’t understand that, but I’m gonna grasp onto something I think I understand.’ ” Like an insurance policy, Carpenter said.

The fire on Aug. 26, 1986 that killed Joby and Jason Graf was initially thought to be a horrible accident. So much so that the charred debris of the shed was taken to the dump that same night by neighbors who were trying to spare the boys’ parents the sight of it. Their empathy destroyed the possible crime scene. The disappearance of that scene gave added importance to eyewitness testimony, testimony that was often contradicted by prior statements and the facts on the ground. Ed Graf’s fate would hinge, in part, on whether the jury put more faith in fire science or in the recollections of the men who fought the fire in his backyard 28 years before.

Trial evidence photo presented by the state of Texas via the Arson Project

Among the first witnesses to the fire was a volunteer fireman named Tom Lucenay, who lived on a street adjacent to Ed Graf’s house. Lucenay had been doing yard work when he noticed the fire, and he rushed to his neighbor’s aid barefoot and shirtless. The population of Hewitt in the 1980s was less than 10,000 people, and the town relied on an entirely volunteer fire department. Lucenay was the deputy chief.

When he arrived, the gate to the backyard privacy fence was chained shut. Graf showed up with his baby in his arms and started to kick down the fence from the inside, helping Lucenay and other neighbors gain access to the backyard to combat the fire.

One of those neighbors, Wilfred Wondra, would be a critical witness for Ed Graf’s defense in both trials. In a statement to police given less than 10 days after the fire, Wondra said that while he was waiting to try to get into the backyard he noticed “the door of the shed was open and flames and heavy gray smoke was rolling out the opening.”

At the new trial, 28 years later, the electrician, by then 82, said that the door wasn’t wide open, but just “a little bit open.” Wondra wore a scraggly beard and seemed to have a harder time than other witnesses remembering things—he had to be reminded repeatedly of what he had said in his 1986 statement.

Another neighbor, William Flake, testified at the first trial that he, too, had seen the shed door open. Flake also testified then that he had seen the boys smoking on “several” occasions, and his son Timothy Flake testified at the new trial that he had seen the boys playing with matches once before. Parts of William Flake’s old testimony were read to the new jury because he wasn’t healthy enough to attend the trial.

Tom Lucenay was the first of a parade of volunteer firemen who would testify on the fourth day of Graf’s retrial that the shed door was closed and locked.

Looking at photos of the scene, Lucenay described evidence that the door had been locked. That day, he had found two slide latches in the debris, picked them both up, and manipulated them. The burn patterns on one indicated that it had been in the open position. The burn patterns on the other indicated it was in the closed position. In his report, Gerald Hurst explained the closed slide latch by noting that there had been interior latches on the double doors that could have been in the closed position whether or not one of the double doors was open, but Graf’s lawyers didn’t raise this point in their cross-examination.

“It’s an absolute scientific impossibility that the doors were closed and the fire progressed to the point where it did,” Reaves, Graf’s lead counsel, told me when I asked him why Hurst’s latch point wasn’t brought up, saying he felt the latch evidence was not significant. Reaves is one of the best appellate lawyers in the state, and maybe even the country. His work on the Willingham and Graf cases had almost single-handedly won Graf a new trial, and thus earned him the right to lead this high-profile defense (he is also a vice president of the Innocence Project of Texas). But he and the rest of Graf’s defense team were stymied by the series of stout, convincing, retired volunteer firemen. (You can watch video of the firemen in this 1986 footage from KWTX.)

For his part, the district attorney, Abel Reyna, was an impressive questioner with a theatrical method: pausing for effect, emphasizing his skepticism at key points, and even stomping about the courtroom in dramatic re-enactments of how the fire might have occurred.

Shortly after Lucenay testified, another former fireman, William Sprung, took the stand to say that the doors were closed. Like several of the firemen called by the prosecution, Sprung recalled events that were now decades old, but much of his testimony was brand-new, describing the events of 1986 in greater detail than had been recorded in previous statements. Sprung didn’t testify at the first trial, but he had given a written statement a week after the fire. In September 1986, he wrote that as he approached the door side of the shed—while manning the nozzle that eventually put the fire out—he noticed it was burned on the outside, and went to the opposite side of the shed to gain entry. This was all he had ever officially said at the time of the fire regarding the door. In 2014, though, Sprung testified that the double door was closed when they approached the fire, and he was certain of this. He said they would have started pumping water through the door had it been open. Instead, they used pike poles to try to pull down the shed walls. Sprung’s recollection was confirmed shortly thereafter by another ex-fireman, Jim Sutter, who had also never before testified if the door was open or closed. He now said that if the doors had been open, they would not have had to use the poles. In his original testimony, though, Sutter had described the front side of the shed as already being “burned down” when they arrived at the scene, indicating there was an opening there to fight the fire. (Sprung did not return a message for comment left with his wife. Sutter did not respond to phone and email messages requesting comment.)

Sutter, a Vietnam veteran and retired military policeman, had been the liaison between the firemen and the family the night the boys died. He was the one who heard Graf tell his wife that both boys were dead when she first arrived home, before Sutter had informed Graf of the discovery of the second body.

There were other possible explanations of how Graf might have known, or at least intuited, that both boys had died in the shed without having placed them there himself. First, everyone who knew Joby and Jason described them as inseparable. According to Graf’s statements, they had left the house that afternoon together. Second, Hewitt’s fire marshal, Jimmy Clark, had said to Graf moments before he was told about the first boy’s death, “Don’t worry, everything is going to be all right. They found the boys.” Clark had thought the boys had been found alive. When he went back to the yard, with Graf right behind him, Clark was told by another volunteer fireman, “You don’t want to go in there.” Clark responded, “Oh, God, don’t tell me that.” All of this was within earshot of Graf. Minutes later, Sutter told Graf officially that one body had been found. (On the stand in 2014, Sutter said that Graf gave “no response” when he told him this. In 1988, though, Sutter had recalled it differently. He’d testified that Graf replied, “Oh, my God.”)

Clark testified at both trials that the only padlock discovered on the scene was found in the unlocked position. That padlock would have been attached to a hasp lock that connected the shed’s double doors from the outside. If anyone had seen that the hasp lock was shut when the fire was put out, then that would prove that the boys had been locked in the shed, almost certainly by Graf. But no witness had ever testified, or given any kind of statement, to that effect.

Photo by Jeremy Stahl

That is until Harold Sokolove, the final firefighter on the fourth day of the trial, came forward. Appearing on the stand wearing a floral patterned polo shirt and having travelled from his home in Puerto Vallarta, Mexico, Sokolove was a stunning witness and a contrast from the staid Texans who had appeared before him. He hadn’t testified at the first trial, and his only previous statement gave nothing in the way of helpful information. But now, Sokolove said for the first time publicly that he remembered that the hasp lock to the shed door was in the secure, closed position. When defense attorney Michelle Tuegel asked why Sokolove hadn’t put that crucial bit of information in his original statement in 1986, he responded that he had only been told to write down what he did, not what he saw.

Sokolove’s testimony ran counter to the investigations of Gerald Hurst and Doug Carpenter, not to mention the contemporaneous eyewitness testimony of William Flake and Wilfred Wondra that the door was open. After his testimony, Sokolove told me that he had initially thought he had mentioned the locked hasp in his 1986 statement. It was only when he realized, in 2014, that the hasp lock wasn’t in his report that he reasoned that he must have been told to put down what he did, not what he witnessed, and had followed the instructions too literally.

“At this point I’ve reached the conclusion that my statement must’ve been based on the instructions to write down what I did,” he told me. “You sort of work backward and think, ‘Well why didn’t I put it in there?’ ”

In other words, he presented the reason for his limited original statement as a memory on the witness stand, but described it to me as a rationalization after the fact. Sokolove acknowledges there’s a chance he could be misremembering the state of the hasp lock, though he believes it to be very slim: “I would give it a 99.9 percent that what I saw on that shed is what I saw on that shed,” he told me.

“They’re asking me to remember what I did and what I saw almost 30 years ago. It’s a little bit of a challenge,” he added. “But that part was clear. It’s almost like there was a spotlight on the hasp lock, and I can see it, I mean it’s like, as clear as day. Everything else that was going on, you know, may be a little fuzzy, but that part for some reason sticks out in my mind, and it always has.”

The first edition of what is now considered the fire investigator’s bible, a document called NFPA 921, “Guide for Fire and Explosion Investigations,” was published in 1992. The manual dispelled many of the myths investigators had relied upon for decades. “The howls of protest from fire investigation ‘professionals’ were deafening,” fire scientist John Lentini wrote of the initial response to NFPA 921. “If what was printed in that document were actually true, it meant that hundreds or thousands of accidental fires had been wrongly determined to be incendiary fires. No investigator wanted to admit to the unspeakable possibility that they had caused an innocent person to be wrongly convicted.”

Photo by Jeremy Stahl

Lentini conducted a landmark 1992 study that proved that certain supposed arson indicators could be produced in accidental fires. He was also among the first forensic scientists to re-examine the Willingham case. He found there was no evidence that anyone had intentionally lit Willingham’s home on fire. At least seven other experts looked into the case and agreed. Willingham had been convicted largely on the word of two fire investigators who had claimed to find more than 20 indicators of arson. All of them were based on junk science.

As late as 2010, the State Fire Marshal’s Office and the governor’s office were still fighting the NFPA 921 standards, at least in the case of Willingham. After David Grann’s story about the many scientific flaws in the Willlingham case, then-Gov. Rick Perry attempted to shut down an ongoing investigation by the state’s Forensic Science Commission into the problems with that case. “I’m familiar with the latter-day supposed ‘experts’ on the arson side of it,” Perry told reporters, using finger quotes. He appointed a political ally named John Bradley to replace the sitting chairman of the FSC. Bradley proceeded to delay testimony by a top scientist in the field named Craig Beyler about mistakes that led to Willingham’s execution and that were ignored by Perry—the testimony would not be heard until after Perry’s primary challenge by Kay Bailey Hutchison had been defeated. (Bradley declined to be interviewed for this story. “I am proud of the work we did and the contribution it made to the improvement of science in Texas,” he wrote in an email.) After the scientists on the Forensic Science Commission rebelled against Bradley and his reappointment failed in the legislature, Perry’s attorney general, Greg Abbott, bailed Perry out by releasing a legally binding opinion decreeing that the FSC lacked jurisdiction to investigate old cases such as Willingham’s. “Abbott is a political hack, and he made his decision to suit Gov. Perry,” Lentini said. (Abbott is now the governor of Texas.)

The FSC did, however, issue a final report describing six different flawed indicators used in the original Willingham investigation. It also released a damning 55-page report by Beyler, the expert whose testimony had been postponed. “The investigators had poor understandings of fire science,” Beyler wrote. “Their methodologies did not comport to the scientific method.” The finding of arson “could not be sustained.”

The Texas Forensic Science Commission chairman tried to convince Texas Cameron Todd Willingham was a monster. Did politics trump truth?

Texas’ handling of the Willingham case was a scandal, but the Forensic Science Commission’s thwarted review resulted in one major achievement. The commission gave 17 recommendations to revamp the State Fire Marshal’s Office, including a proposal that the fire marshal review old arson cases where questionable science was used—exactly what Abbott had told the FSC it couldn’t do. Surprisingly, the state’s new fire marshal accepted every single one of those recommendations, including the work of reviewing old cases. Ed Graf’s case was among the first up for review.

The forensic myths used in Graf’s 1988 trial were mistakes common to investigations of fires that reached a stage called flashover, which is when everything in a room has caught fire. The key indicator used against Graf was “alligator” charring, one of the kinds of evidence most commonly misinterpreted by investigators evaluating a fire in a wooden structure. “Alligatoring” is when wood blisters to the point that it looks like alligator skin. Large rolling alligator blisters were long believed to indicate that a fire had been fast and hot, and was thus the result of a liquid accelerant. NFPA 921 explicitly discredited these patterns as arson indicators.

False arson indicators like “alligatoring” were taught to fire investigators across the country, who were usually not trained as scientists and had little basis for challenging what they learned. This education gap has made the field more susceptible to junk science than fields practiced by degreed scientists, such as forensic pathology and DNA testing.

Since NFPA 921 started to gain widespread acceptance as the standard in the late 1990s, the number of fires determined to be arsons in this country has decreased dramatically. Between 1999 and 2008, arsons dropped from 15 percent to 6 percent of fires nationwide. A study by former Texas Observer editor Dave Mann, who was the first reporter to cover the faulty fire science used in the Graf case, showed that Texas had a 60 percent decrease in incendiary fires between 1997 and 2007. There are probably multiple reasons for this trend, but one obvious explanation is that fewer false arson determinations are being made based on bad science.

Since the Willingham execution and its ugly aftermath, Texas finally started taking arson science more seriously. In 2012, Chris Connealy, a former Houston fire chief, took over the state’s battered Fire Marshal’s Office and quickly made it into a model for fire investigators around the country. He had none of the baggage of previous officials who had sided with the Perry administration during the Forensic Science Commission’s controversial Willingham investigation. In addition to starting the review panels, Connealy doubled training budgets for his office’s investigators, added an electrical engineer and criminal analyst to his staff, and made his investigators take part in mock hearings to see if their expertise would hold up in court.

Shortly after entering office, he sent a letter to fire officials throughout the state, promising changes, including a more hardline stance on investigators who were unable to prove their scientific expertise to judges during legal proceedings. “A fire investigator that fails to be acknowledged by the court as an expert will likely no longer have a career as a fire investigator,” he warned.

Photo by Sebron Snyder

It wasn’t just tough talk. Within a year, 20 percent of his office’s staff had left, many unable or unwilling to meet the new training standards. When I met Connealy at the end of 2013, he told me that five members of his office had departed, and one had announced his retirement that day. We met over cheeseburgers and beer at Londoners Pub in Plano, where he was running a quarterly training conference he had set up as part of his response to the Willingham report. During these conferences, the state’s arson review panel looked at old cases brought to them by the Innocence Project of Texas. With Connealy were friends from the Louisiana State Fire Marshal’s Office, including Fire Marshal Butch Browning, and two of the most renowned fire scientists in the country, John DeHaan and David Icove. The scientists had been called in by Connealy to speak at the training seminar and serve on the review panel.

As the Louisiana fire contingent watched the New Orleans Saints on Monday Night Football, DeHaan and Icove chatted about the latest major arson exoneration. An Arizona man had been released from prison that past April after serving 41 years for a hotel fire that killed 29 people. Icove and DeHaan lamented the fact that the exoneree, Louis Taylor, did not get a dime from the state in restitution. The district attorney had threatened to re-prosecute him, so Taylor pleaded no contest in order to ensure that he would win his freedom. “He just wanted his life back,” DeHaan said.

Connealy had more prosaic worries. “A very large urban fire department” in Texas had an annual training budget of just $3,000—Connealy’s training budget was more than 150 times that size—and still, that city had more people investigating fires than Connealy’s office did, people who could potentially perpetuate arson myths. “That’s a concern,” he had told me in an earlier interview. “Training is how you overcome these myths and know the current science.”

Connealy’s actions to change the state’s culture have earned him widespread recognition. In 2013, he was a finalist for the Dallas Morning News’ Texan of the Year. “Connealy has done as much as, if not more than, anyone else in Texas law enforcement to seek out the truth, improve our system and push our state forward,” wrote Innocence Project of Texas policy director Cory Session in putting forward Connealy’s nomination. The fact that this endorsement was coming from the state’s Innocence Project, which had been severely critical of the previous fire marshal, spoke to Connealy’s efforts to collaborate with them. The arson review panel was the first, and still the only, of its kind in the nation. Last August, Connealy was awarded the National Association of State Fire Marshals’ top honor. And at the end of 2014, Governing magazine named him one of its public officials of the year.

Photo by Jeremy Stahl

I attended Connealy’s quarterly training session in December 2013, where the topic was how to use dogs to detect accelerants. Dogs are excellent tools for fire investigators—the positive rate for lab samples from the State Fire Marshal’s Office increased significantly when canines were used to pull samples, according to one analysis described at the conference—but they are by no means perfect. For example, dogs can’t always discriminate between petroleum-based products and intentionally placed ignitable liquids. Over the course of the conference, the standard of NFPA 921—that unless a canine alert is confirmed by lab analysis, it should not be considered valid—was emphasized repeatedly. DeHaan mentioned during the presentation that prosecutors still pressure dog handlers to ignore these scientific guidelines and testify to alerts that were not confirmed by lab results. “When I get on the stand and I start talking about dogs, you see people wake up in the jury box,” said canine unit captain Tommy Pleasant to a room full of 80 or so firefighters and investigators. “If you’re going to let these 12 people that weren’t smart enough to get out of jury duty determine somebody’s civil liberties—whether or not they’re going to spend the rest of their life in prison—we got to do it right.”

DeHaan had investigated the Ed Graf case back in 2010, and like Carpenter and Hurst had found that “if the doors were latched close … there would be insufficient ventilation to permit more than an initial flash fire.” In a report he put together for Graf’s lawyer Walter Reaves, DeHaan described how the high level of carbon monoxide inhaled by Jason and Joby would not have made sense in a set gasoline fire, which concurred with Carpenter’s findings.

In the middle of DeHaan’s presentation at the quarterly training session, he had a lengthy exchange with a skeptical fire investigator. The questioner asked if he thought a dog alert should never be considered valid without a lab confirmation, and DeHaan was adamant that, yes, he did. The questioner then described a case where a suspect had confessed to pouring an accelerant exactly where a dog had detected, but a lab test had failed.

“You can’t argue, ‘well, he said it was there, and therefore the canine is right and the lab was wrong,’ ” DeHaan responded. “You just have to say there’s no evidence of it.”

When the questioning investigator pressed him, DeHaan went even further.

“Confessions are really, really unreliable,” the brusque California scientist preached to the room of Texas law enforcement officials. “I get involved in all kinds of cases today: ‘Well, he confessed.’ And I point out at least seven people confessed to being Jack the Ripper. That means at least six of them were lying. So confessions to me mean virtually nothing.”

“If we’re going to send somebody to jail for life, or to the death penalty,” he continued, “we better be absolutely certain.”

The fact that the state had actually executed someone on the basis of unreliable arson science—the very reason that these training conferences were taking place—was the subtext of the entire two-day seminar. During his remarks, Connealy only hinted at why they were there, talking about “rebuilding the reputation” of the State Fire Marshal’s Office and using the “Forensic Science Commission report”—that is, the Willingham report—to accomplish this. “We got some negative publicity,” is how another speaker, investigator Tommy Sing, put it to the assembled crowd.

“I can tell you looking at the Graf case, there’s no forensic evidence to support the conclusion that the fire was intentional,” Sing told me between conference sessions. “Not then, not now.” Sing, a 40-year veteran firefighter and investigator, had investigated the case at the appellate stage for the McLennan County prosecutor’s office. Still, he was sure to offer the caveat that this was a forensic science point of view and not a “criminal investigation point of view.” In all of his 2,000-plus criminal investigations, though, Sing had never had a prosecutor charge someone with a crime in an undetermined fire. As for Willingham, Sing seemed to acknowledge that the execution was a travesty of justice without saying he was innocent.

“We can’t go back and change anything that’s already happened—we can’t change Willingham,” Sing told me. “But today,” he continued, taking a deep sigh, “today I’m glad it’s in the forefront. Because it’s getting better training for my investigators.”

A profile of Cameron Todd Willingham’s family and their campaign to have him exonerated.

The new message seemed to be getting across. “Nobody likes having their work reviewed, but I think in this day and age it’s necessary,” said Austin Lieutenant Investigator Brooks Frederick.

Frederick has been an investigator for 30 years, most recently as a canine handler, and when he joined the force he was taught many of the same shoddy investigative techniques that were used in the Graf and Willingham cases. Now he remembers his first arson class as a rookie investigator in January 1984 and can’t believe what was being taught.

Investigators used to say that tar and soot on a glass window meant that an accelerant had been used. “That’s bullshit,” he said. “That’s typical of most fires.”

In 1992, another myth about “crazed” glass was used to prove that Willingham had killed his children. “If you saw the crazing, cracked or irregular [glass], ‘my God ignitable liquid,’ ” Frederick remembered. “Bullshit! A fire hose will do that.” When cold water hits a hot window, the windowpane will crack.

Concrete marked by chips, holes, or discoloration used to indicate that a fire had burned hotter than normal. “Oh man that was ignitable liquid right there, buddy,” Frederick said. “Bullshit!”

Even Joseph Porter, one of the original investigators on the Graf case, agreed that the science had changed enough to warrant his work getting a re-examination. “Some of the issues that were used in the first trial—such as the burn patterns, and alligatoring, and charring, and things like that—aren’t the reliable things that we thought they were in 1986,” he said. Porter still believed in Graf’s guilt and was unhappy that neither Connealy’s panel nor the state’s prosecutors had spoken to him about the case, but he acknowledged that relying on photos to make his determination might not have been the right approach. (He also said that he was so reluctant at the time of his initial investigation to go ahead to trial based on the evidence he had that he insisted a second fire investigator be brought on to confirm his findings. “I did not feel comfortable saying that, just based on the hearsay and the background circumstances—I was very uncomfortable taking that to a jury in a case that would be a murder case,” Porter told me.)

Photo by Tamir Kalifa

Nearly everyone I spoke with about the arson review panel described it as something that should be adopted across the country. “Texas is leading the way on this,” said the then-executive director of the Innocence Project of Texas, Nick Vilbas, who was in Plano to attend the conference. (Vilbas left the Innocence Project of Texas in June.) His group had combed through 700 old arson convictions to identify cases for the review panel to re-evaluate.

Vilbas, a 32-year-old criminal defense attorney, wears multiple ear piercings and tattoos. One of his tattoos is a Texas map, with a Texas flag behind it, two yellow roses, a blue bonnet and thistle with a banner that reads “Deep in the Heart.” (“As much Texas as you can fit into a tattoo,” Vilbas says.) Another is a bald eagle with the slogan “Liberty Justice for All” with a big bold asterisk. Everyone in Texas can get behind the idea of being the best at something, he says, even when that something is criminal justice reform. “If there’s one thing that I think Texans can appreciate, it’s being willing to lead the charge,” Vilbas said. “That’s what we are as a state.”

Despite the new testimony from the firefighters about the lock on the shed door, the outcome of Graf’s second trial seemed hard to predict at the end of the first week. The prosecution had shown that Graf was thoughtless toward his wife in the aftermath of the boys’ deaths. It had shown that he stood to benefit financially from the boys’ deaths. But it hadn’t demonstrated that Graf had killed Joby and Jason. It also hadn’t yet called its star witness, Graf’s ex-wife Clare Bradburn.

Later in Graf’s second trial, friends, neighbors, and the boys’ teachers would testify that Graf appeared to have been a good dad. He had chosen to adopt the boys, whose biological father had relinquished custody after failing to pay child support. He was proud of them taking his name, and he was an active parent, cooking for them, taking them to sporting events, playing an active role in school, and helping them with homework.

Photo by Jerry Larson/Waco Tribune Herald via AP Images

Clare Bradburn’s direct examination painted a different image. She testified that he was a domineering presence, a man who was so obsessed with her as to insist that she kept the door open when she went to the bathroom. Her family, meanwhile, depicted Graf as a militaristic disciplinarian who physically abused the children on at least two occasions.

Bradburn was a compelling witness—a beautiful, kindly elementary school teacher who had devoted her life to children only to have her first two sons ripped away from her. On cross-examination, however, defense attorney Mark Dyer worked hard to demonstrate her biases.

Dyer had history with Graf’s case: He had been at Baylor Law School and had worked as a “research grunt” for Graf’s defense team in 1988. At the time, everything except for the forensic evidence had convinced him that Graf had been innocent. “The circumstantial evidence … didn’t resonate to me as being evidence that he committed a crime,” Dyer told me before the second trial. The only thing that gave him pause was the certainty of the forensic experts. Dyer believed that if it hadn’t been for that forensic evidence, which has proved to be faulty, Graf would have been acquitted.

Dyer eventually became a partner at a major civil firm in Dallas. When he heard Graf was getting a new trial, he called Reaves and volunteered his services pro bono, his first criminal case since Graf’s original trial. Now Dyer was cross-examining Clare Bradburn on the stand, and question after question was landing. He portrayed her as a woman in denial for her refusal to believe her sons might have set the fire. Under questioning, she acknowledged that during her career she had taught good kids who had made bad choices and that there’d been times when parents of misbehaving students had told her “my kid would never do that.”

He also got her to admit Graf shared responsibilities of cooking, cleaning, and taking the kids to school. It was his idea to adopt the boys, and their grades and behavior improved once he came into their lives. He bought the boys an Atari. He took them to the Texas coast and Six Flags and church and Sunday dinners at his mom’s house. When Jason got pneumonia, Graf stayed with him overnight at the hospital while Clare took care of the baby and Joby at home. Graf attended soccer and T-ball games with them. He acted like he cared for them.

Bradburn had testified that not only would the boys have never played in the shed, they didn’t play in the backyard, which she said was “dry” and full of thorns. But again, on cross-examination, Dyer poked holes in Bradburn’s account. One month before their deaths, Graf had bought the boys a tetherball set as a present and installed it in the backyard, digging a hole in the yard, pouring concrete in the ground and setting it. Under Dyer’s questioning, Bradburn remembered her sons playing with the tetherball.

On the stand, Bradburn admitted that the life insurance purchase had not been a secret and that they were both beneficiaries. She said it was true that she had “bitterness and bias” against Ed Graf and that she refused to acknowledge the possibility that the fire was an accident.

Dyer’s cross-examination was a seemingly devastating challenge of the state’s most important witness. It was also when the proceedings seemed to turn against Graf.

During Bradburn’s testimony, the prosecution had asked her how many times she and Graf had been “intimate” in the lead-up to the fire. The point was to show that their marriage was failing. She responded only “three or four” times between February and August. “We had many weaknesses, that was one of them,” she said.

Dyer returned to the sensitive issue. He noted that doctors recommended waiting six to eight weeks before having sex after a C-section (which Bradburn had for her third son), and that new parents are generally wiped out. He asked her about her breast-feeding habits and implied the lack of sleep might have been what kept them from having marital relations. Dyer didn’t succeed in proving that Clare and Ed had had a good marriage, but he challenged Bradburn’s account of their struggles. It was a particularly harsh portion of a harsh round of questioning.

Photo by Jeremy Stahl

When Bradburn’s cross-examination was over, the prosecution made a surprising request. They moved to have the evidence of Graf’s embezzlement admitted, midtrial. This testimony had never been allowed in court, except in the sentencing phase of the first trial, because it was viewed as prejudicial. Now, though, while the jury was out of the courtroom, prosecutors argued that the defense had opened the door for it by describing vacations and the Atari that Graf had bought the boys, which prosecutors said painted a misconception about Graf’s finances and mattered for the purposes of his alleged motive.

“The fact that he got an Atari does not open the door on embezzlement,” Dyer countered. He argued that allowing the embezzlement evidence would so turn the jury against Graf that the rest of the trial wouldn’t even be necessary. “You might as well declare that man guilty now, that is how prejudicial that is,” he said.

After hearing arguments from both sides, the judge made an extraordinary ruling: He decided to reverse himself and admit the evidence of Graf’s embezzlement. “I’m going to lift the order,” he said, and adjourned the court for the day. Graf and his legal team were devastated, and Dyer spent the entire night looking for an argument that might change the judge’s mind. When he was unable to do so, Dyer asked for a hearing so that the judge might explain why the embezzlement was now relevant to the proceedings.

“You’re asking me to explain my ruling? The court of appeals explains my rulings,” Judge Matt Johnson responded.

The prosecution was supposed to restrict its references to the embezzlement to questions regarding Graf’s financial motive, but it was used repeatedly as character evidence throughout the rest of the trial. Many of the remaining witnesses were asked some variation of the question “if you had known that this man had stolen from his employer for 12 years, wouldn’t it have made you suspicious of him?” The defense objected every time, and the judge overruled them every time, eventually granting a running objection to be recorded for appellate purposes. Johnson’s office did not respond to a request for an interview.

After Clare Bradburn’s testimony, the prosecution had one more ace up its sleeve.

In April 2014, with a trial date for Ed Graf just weeks away, McLennan County District Attorney Abel Reyna began receiving letters from a prisoner named Fernando Herrera. He was a new cellmate of Graf’s, and according to his letters, Graf had confessed to murdering Joby and Jason, describing the crime in astonishing detail. At the start of May, Reyna requested and was granted a continuance that pushed the trial back past the summer. Herrera would become a crucial witness in his prosecution against Graf. He would testify at trial that he had come forward with this information without any expectation of reward. (Reyna’s office declined repeated requests for an interview about the case before and after the trial. During the trial, he couldn’t comment on the record because of a gag order by the judge.)

On the seventh day of Graf’s trial, with the courtroom’s window shades drawn so that no members of the media could snap the inmate’s photo or film him, Herrera took the stand to say that Graf had described exactly how he had committed the crime and why, including such minute details as his not filling a Dimetapp prescription for Jason.

The 38-year-old Herrera had a long criminal record, which was laid out at trial by both sides. As the lead prosecutor himself described it, Herrera had “quite a résumé.” He had been in and out of prison since he was 18, had at least 14 criminal convictions according to the Waco Tribune, and had used at least a half-dozen aliases with authorities. Herrera had four charges in McLennan County of theft and drug possession pending against him when he testified. Among Herrera’s crimes were at least five separate prior convictions for lying to authorities, including multiple charges of giving false information to a police officer.

On the stand, Herrera demonstrated an almost encyclopedic understanding of the prosecution’s case against Graf. But at times he seemed to depart from one version of events and then reverse himself, or be interrupted by the prosecutor in the midst of an apparent detour. And on occasion Herrera’s testimony matched previous testimony verbatim. “What Hererra has to say is what the state wishes they could prove but can’t,” the defense team would argue afterward, noting apparent holes in his story.

Early in Herrera’s testimony, the lead prosecutor, Michael Jarrett, asked him why he decided to come forward. “I remember kind of getting intrigued by the case because of the women that were testifying against [Graf],” he said, at which point Jarrett cut him off. It sounded as though Herrera was describing having read about testimony in Graf’s previous trial, or perhaps even having seen a trial transcript. If Herrera’s testimony was based on anything other than his conversations with Graf, then it could have been thrown out.

Drawing by Tom Lucenay

Herrera also brought back a long-abandoned claim, for which there was no forensic evidence, that the boys had been tied up. “[Graf] mentioned how he strategically placed the rope so he couldn’t be convicted of it,” Herrera said. “They were just put in there in a way that nobody could say that he tied anybody or anything up.” If Ed Graf did confess to tying up the boys, he was confessing to something that contradicted the autopsy report, which showed no indications the boys had been tied or drugged, and the assessment of the initial firefighter at the scene, Tom Lucenay, who said in the first trial that he saw no such evidence. One potential reason for Herrera to mention this debunked theory: In Lucenay’s sketch of the fire scene, available online when you Google the case, there is a drawing labeled “rope” near the boys’ bodies. (Another potential explanation is that in Ed Graf’s testimony from his first trial he mentioned that Clare had accused him of tying up the boys. Graf’s legal team said he kept portions of the transcript with him in jail, unsecured and easily accessible.)

In addition, Herrera brought up “alligator skin” charring, saying that Graf had used special arson techniques so “they wouldn’t be able to pinpoint the start of the fire.” Though “alligator charring” was not a feature of this new trial because it had been debunked, it was mentioned frequently in previous public records and accounts of the case. Apparently, if Herrera’s account is to be understood, Graf’s master plan was to use specially acquired arson skills to set an ‘undetectable’ fire by creating a pattern that—after he had spent a quarter-century in jail—would prove key to helping him win a new trial once it was identified as a faulty forensic indicator thanks to modern science.

Additionally, Herrera claimed that Graf told him he’d set the fire, strategically locked the shed door for long enough to have “made it seem” like asphyxiation killed the boys, then opened it so that the early witnesses on the scene would see an open door. Again, this line of testimony suggested that Graf had taken actions in 1986 that anticipated advances in fire science not made until decades later.

Herrera also attributed to Graf a handful of crude quotes that seemed irrelevant to Graf’s guilt or innocence. Graf allegedly told Herrera that he was planning to “pull an O.J.” and that if the “glove don’t fit you must acquit.” Herrera testified that Graf called Abel Reyna a “chicken-shit motherfucker.” Reyna, who was previously sitting at the bench impassively while the assistant DA questioned Herrera, gave a side-glance toward Ed Graf at this moment.

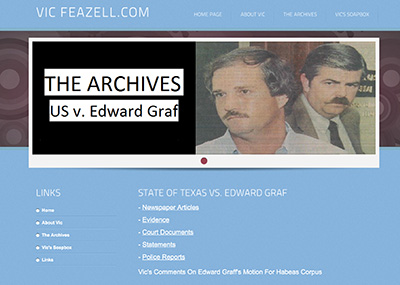

Screenshot of Vic Feazell’s website

At one point, Herrera described how firemen had asked Graf if they could take away the shed because it was being described as an “eyesore.” Lucenay had used the word “eyesore” in his second trial testimony four days prior to Herrera’s testimony—and months after Graf’s alleged confession—and had been quoted using the word in the Waco Tribune.

In fact, much of the information in Herrera’s description of the confession was readily available elsewhere. In his testimony and in correspondence, Herrera told authorities dozens of details that were either on the website of the former prosecutor, in articles about the case online, or in original trial transcripts and documents Graf’s legal team says he kept among his personal belongings in jail, easily accessible to other inmates. (When he was asked whether or not he had gotten into Graf’s stuff, Herrera at one point said “if he had any of that in his box, then something was wrong with him, wouldn’t you agree?”)

In one letter to Reyna, given to me by defense attorneys, Herrera makes it clear that he’s at least aware of specific documentation about the case. “I know about the letter that was sent to you on behalf of his case from the Texas Insurance Group, State Fire Marshall, and Hewitt Police Department, and about the scientific evidence,” Herrera wrote. (He claimed elsewhere that Graf told him about this document.)

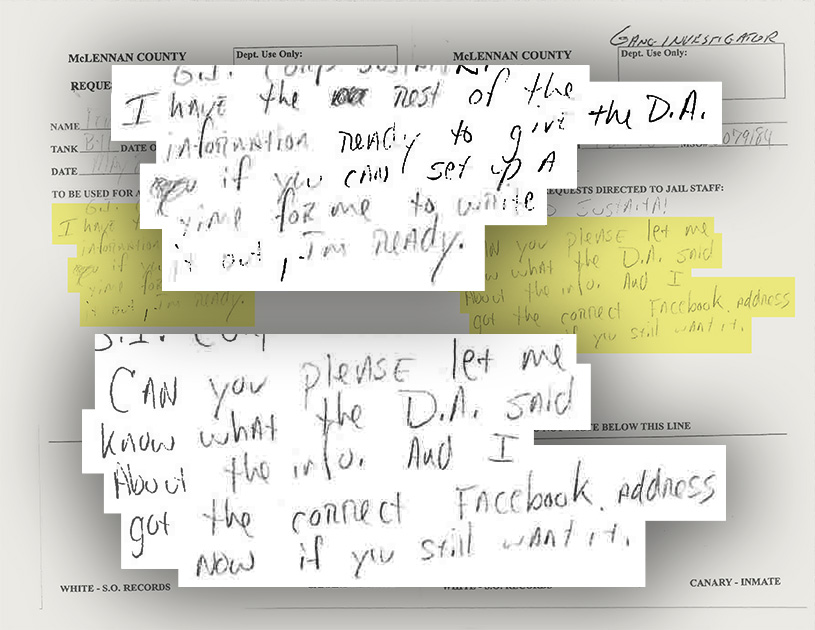

Herrera also appeared to mislead the jury about whether or not he would have had the ability to get such information. He said that he did not have access to the Internet or Facebook, where he might have found public information about the case. But there is evidence, including his own testimony, that Herrera did have the ability to get information from the Web. One week after first contacting Reyna, Herrera wrote to his jailer with a request: He asked the prison guard to “let me know” what an unnamed district attorney had said about the “info” and added “I got the correct Facebook address now if you still want it.” On the stand he admitted that he could and did get Web information, such as Facebook addresses, by contacting friends on the outside—seemingly contrary to his earlier testimony about lack of Internet access.

Three days later, Herrera wrote to his jailer “I have the rest of the information ready to give the DA if you can set up a time for me to write it out, I’m ready.” The next day he sent a five-page letter to Abel Reyna that would form the basis of his testimony against Graf. Later he wrote again directly to Reyna asking for help: “When you get time I’d like to talk to you personally about some agreements we could come to,” Herrera told the DA. “I come to you in the most modest, humble, and respectable way and I’m willing to go to whatever lengths according to the law and your stipulations on this matter.”

Graphic by Lisa Larson-Walker. Document courtesy of Mark Dyer.

Which raises another potential problem with Herrera’s testimony: He appears to have benefited from it and to have vigorously pursued those benefits. (Slate requested comment from Herrera through his lawyer and his mother; his mother told us that he was wondering if we would pay him for an interview. We told her it wasn’t Slate’s practice to pay for interviews; she eventually told us, “He said he wasn’t going to do it unless y’all paid him.” Herrera’s lawyer also told me that prosecutors did not offer him any plea deal in exchange for his testimony.) Herrera had been an informant in a handful of other cases in recent years—including at least one other murder—and described in writing his hopes for rewards for sharing information with authorities in several cases.

On the stand Herrera said he had no expectation that he would be helped in return for his testimony in this case and had not been promised any reward. An official from McLennan County Sheriff’s Office also testified that Herrera had not been given any benefits in exchange for his promise of testimony. (Prosecutors are legally obligated to disclose such deals.) But the record implies something different.

McLennan County has an ugly history of using jailhouse snitches to get convictions that were later overturned when the snitches recanted and said they were bribed. Graf’s original trial was the fourth murder conviction in a capital case won by former district attorney Vic Feazell to later be overturned. In the three previous instances, revelations about faulty jailhouse testimony and multiple accusations of quid pro quo deals with inmates (including some claims of conjugal visits being among the benefits to cooperating inmates) came to light. In one case that relied heavily on jailhouse witnesses, two men were released many years into serving life sentences for a murder and sexual assault that DNA evidence ultimately proved another man had committed. (Feazell declined a request for an interview.)

It was difficult not to be reminded of this troubling past while considering Herrera’s testimony. Before volunteering to testify against Graf, Herrera had made repeated pleas to become a trusty at the McLennan County jail between August 2013 and April 2014, but had been denied every time. Jailhouse trusties get better prison jobs, better accommodations, visits with family, and time credited toward their sentences. Herrera’s requests were rejected because rules said that inmates needed medium security status in order to be classified as trusties, and Herrera was a maximum-security inmate. In his request forms, five of which were written in a month-long span a few weeks before he started cooperating on the Graf case, Herrera’s desperation to become a trusty is palpable. In one form on March 15, he specifically links a trusty request to cooperation in a separate case saying that an officer “said that after the statement I signed y’all would get me in.” It wasn’t the first time he had specifically requested something in exchange for cooperation. In August 2012, he told jailers “I have some info for you. … I will cooperate if you will help me. Ask about me and you will see I’m telling the truth.” (On the stand, he said the help he was requesting was to be “moved to a better cell” in order to avoid a fight.)

Herrera was ultimately made a trusty in mid-June and had his security status reduced to medium security, according to Dyer’s description in court, after he began communicating with Reyna in April and before he testified at Graf’s trial in October.

Meanwhile, while seeking trusty status in 2014, Herrera had also pursued at least one other avenue of aid from his jailers—and this one he explicitly linked in writing to his cooperation in the Graf case. After volunteering to help on the Graf case, he sent a note to law enforcement officials asking for his bond to be reduced, noting his cooperation in this case and others as a reason for the judge to reduce it. The bond request was dropped, but Dyer argued in court—outside the hearing of the jury—that it was reasonable to ask Herrera if the bond request mentioning Graf and the trusty status that Dyer said happened “right after” were linked. “After the last letter is done then he makes trusty, that’s just too coincidental,” Dyer argued. “[It’s] not just what he’s gotten, it’s about what he thinks he’s getting.” The prosecution objected because they said it was an “attempt to poison the jury” and Dyer did not end up asking that specific question in front of the jury.

At one point on the stand, Herrera seemed almost to acknowledge that he hoped he would be rewarded for his testimony before reversing himself. When he was asked by the prosecution if “deep down” he thought something good was going to happen to him, he started to answer “I want to be able to—” before cutting himself off and concluding “not in exchange for this, no.”

There was one final problem with Graf’s alleged confession: It was incredibly recent. Ed Graf had maintained his innocence throughout the lead-up to his first trial and for at least 25 years afterward. The supposed confession to Herrera was made in county jail, where Graf was waiting for a new trial that could potentially set him free, scheduled for just weeks away. No other inmate had made such a claim from the entire time Graf was locked up in the state penitentiary.

Judge Johnson did not allow Graf’s attorneys to ask Herrera why Graf would maintain his innocence for more than two decades and then, on the verge of winning his freedom, decide to confess a double murder of his adopted children to a cellmate he had known for a couple of weeks. This question, Johnson ruled, would alert the jury to the fact that this was Graf’s second trial, which Johnson had previously said could bias them. Johnson’s order meant this one crucial question to Herrera—why did Graf keep his mouth shut for so long in prison and then talk to you—was out of bounds.

Fernando Herrera was telling the truth about at least one thing: Ed Graf really did say several of the lines Herrera attributed to him. Graf said that he and his lawyers were going to “pull an O.J.” in his trial and that “if the gloves don’t fit you must acquit.” He really did call the district attorney that was prosecuting his case a “chickenshit motherfucker.” He also said of the lead prosecutor in his case, “whatever dumbass came up with [my eight-count] indictment is a dumbass.” We know all this because Graf was caught on tape saying these things to his friend Rick Grimes during visitation sessions. He never confessed on these tapes, and he maintained his innocence to his friend. But all of the above statements matched parts of Fernando Herrera’s testimony.

These quotations don’t necessarily validate that testimony—Herrera could have acquired this information by other means (the defense team noted that the phone conversations occurred in a very public space), and then used these details to give his testimony some added authenticity. But at the end of closing arguments, Grimes’ conversation with Graf was used to demonstrate that everything Herrera had said was true. No matter how he came to know them, Herrera being able to repeat these small details—things that were otherwise irrelevant to the case—made him appear believable in the eyes of the jury. Patricia, a juror who asked that I not reveal her surname, said that she was skeptical of Herrera’s testimony until Grimes’s testimony. “I wasn’t real sure that it was real credible at first until I heard the last witness,” Patricia said. “Hearing that made me decide that his information that he gave was partially true.”

Photo by Jeremy Stahl

The defense’s case was not nearly as dramatic as Herrera’s testimony. Many of the defense witnesses were unable to attend, and the ones that did sometimes had difficulty with their memories. One witness changed his story to say that he caught Jason playing with matches three times instead of the one time he originally testified to in the first trial. Still, at least four witnesses testified—or had previous testimony read for the court—that they had seen the boys play with matches or cigarettes. Another witness, whose previous testimony was read at trial, was a maid who said she’d found cigarettes in the family’s guest room and a cigarette butt in the boys’ room, and another witness testified that Jason walked across hot coals during a camping trip.

The defense’s star witness was the fire scientist Doug Carpenter. He presented his theory that the large amount of carbon monoxide in the boys’ lungs indicated that they were likely knocked out by the fire’s fumes before dying, and were trapped that way rather than by being placed in the shed and having the door locked. But the prosecution was able to ding that theory by bringing up a capital murder case where his carbon monoxide theory did not convince a jury and another case—which Carpenter never analyzed—where a murder confession appeared to contradict it.

Carpenter spent a large part of his early testimony trying to lay down some basic facts about the history of the scientific method and fire science that frequently became arcane and hard to follow. (At one point he explained, “the sun is a hot body that can radiate energy to the Earth.”). For the most part, the jurors did not understand the scientific arguments, according to Patricia, the juror I spoke with, and got bogged down by jargon like “flashover,” which they had trouble understanding. “He spoke above all of our heads with his terminology,” she said.

Carpenter also discussed a computer model he used to show that the doors had to have been open for sufficient air to feed the fire, but the judge blocked him from showing the model in court or describing it as a government system due to prosecution objections. Prosecutors were able to convince jurors that his modeling—which had been affirmed by pioneering fire scientist Gerald Hurst and was never really challenged up until that point—was not precise enough. “To plug variables into a computer and say this is how this happened—I just didn’t belie—not that I didn’t believe it—it just didn’t … convince me,” Patricia said after the trial. “I wrote a lot of the information down, but I never went back to it.” Most of the jury agreed the door was likely closed, she said.