Occupying the First Amendment

What the actions over Zuccotti Park teach us about public spaces and citizen protest.

For nearly 60 days, demonstrators gathered in Zuccotti Park, a privately owned and very publicly occupied sliver of lower Manhattan, to Speak Truth to Power at what has become the hub of the Occupy Wall Street movement. But last night, Power was in no mood to chat. So shortly after 1 a.m. several hundred New York City Police surrounded the park dressed in riot gear, illuminated the encampment with klieg lights, and delivered—on behalf of Power—the same message that made Max von Sydow so charming in the Exorcist: “Get out.”

And get out they did. In a few hours time, over 200 demonstrators were arrested. Police cordoned off streets approaching the park, keeping the curious, the sympathetic, and most notably the press away from the action. Several journalists reported being roughly handled by police in the process, and an order closing the air space over lower Manhattan ensured that news helicopters couldn’t get footage of the raid.

That was the state of affairs when the First Amendment right to peaceably assemble smashed into the right of cities to protect their parks. And that was the state of affairs at 8 a.m., when Mayor Michael Bloomberg issued a statement affirming his deep regard for the First Amendment. He proceeded to give the sort of stern lecture about rights and responsibilities that sitcom fathers give their badly behaved teens, the tenor of which was that while free expression is generally a good thing, this nonsense had gone on long enough, and the city of New York had run out of patience.

It is no exaggeration to say that what happened overnight could be a watershed moment for the Occupy Movement: Frankfort, Ky., San Francisco, and Cincinnati have all been occupied, but the encampment near Wall Street has been the spiritual and symbolic center of a leaderless movement that has taken the example of Zuccotti Park and turned it into a moral franchise of sorts around the world.

The question of whether OWS has worn out its welcome with municipal leaders seems to have been answered in the affirmative tonight. Two weeks ago, Oakland police used tear gas, rubber bullets, and flash grenades to disband the Occupy camp outside city hall, on orders from Mayor Jean Quan. Police in Atlanta, Albany, N.Y., Cincinnati, Nashville, Tenn., Salt Lake City, Portland, Ore., and other cities have also moved to evict Occupy demonstrators from public spaces in recent weeks.

Like Philadelphia Mayor Michael Nutter, many have complained that the encampments in their own cities have changed as dedicated protestors were joined—and to hear city official tell it—outnumbered by homeless people, drifters, and petty criminals. Camps, hailed early on as experiments in direct democracy, were evidently descending into chaos. This morning, Michael Bloomberg cast his lot with the doubters, and made it clear that in his New York, free expression will not come at the expense of public order:

From the beginning, I have said that the City had two principal goals: guaranteeing public health and safety, and guaranteeing the protestors’ First Amendment rights.

But when those two goals clash, the health and safety of the public and our first responders must be the priority.

You cannot fault Bloomberg for his goals; they embrace the fundamental tension at the heart of the First Amendment and public protest. Case law dealt the Occupy movement some fairly heavy cards. Their speech, on matters of core political concerns, sits at the top of the pantheon of what the First Amendment protects. And while Zuccotti Park is technically private, it functions as a public park, and was dedicated under local zoning laws for round-the-clock public enjoyment in 1968. Public parks enjoy an exalted status in the geography of the First Amendment, enshrined in the sort of language men like the first Justice Roberts used to conjure images of the Periclean agora:

Wherever the title of streets and parks may rest, they have immemorially been held in trust for the use of the public and, time out of mind, have been used for purposes of assembly, communicating thoughts between citizens, and discussing public questions. Such use of the streets and public places has, from ancient times, been a part of the privileges, immunities, rights, and liberties of citizens.

But practice First Amendment law long enough, and you learn that for every uplifting paragraph like that, there are a thousand cases bending an abstract right to the prosaic realities of protest.

By and large, the government gets to decide the terms on which even exalted places like Zuccotti Park are used for demonstrations, within limits defined by almost a century of case law. We saw that tonight. The rules speak to transparency and neutrality. The government can almost never deny access to a forum because it objects to the message the speaker wants to deliver. It can regulate who gets to use a forum to prevent inconsistent claims (like competing Thanksgiving Day parades), but generally it must do so according to clear, neutral guidelines so that the game cannot be rigged. It can impose limits on the volume of loudspeakers or the route taken by a parade.

In the First Amendment trade these are known as time, place, and manner restrictions, and courts will generally defer to the government if a restriction is crafted narrowly and designed to advance a significant governmental interest. Of course cases over restrictions on free expression in public spaces tend to turn on whether the interest asserted by the government is real, not pretextual, and whether the rule at issue actually moves the ball forward. Which brings us back to the events of this morning.

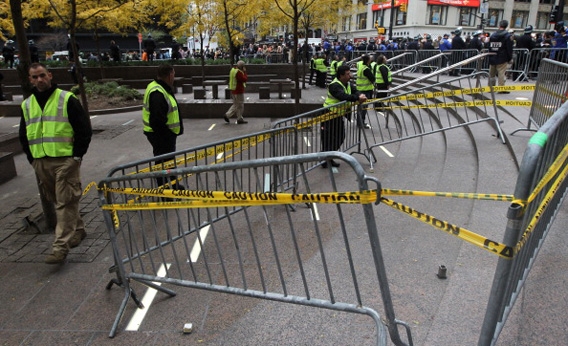

Mario Tama

When Power evicted the demonstrators today, it told them to take their tents, structures and bedrolls with them, but promised they could return, sans mattresses, once Zuccotti Park had been cleaned. The need to clean the park may or may not have been a pretext for evicting the demonstrators—who several weeks ago took the job of cleaning the park in hand themselves. But the core dispute in the case—as it has been in other cities—is whether the demonstrators can use the park as an encampment. The city argued that such a use is inconsistent with the use of the park by the general public for “passive recreation.” And this afternoon, a state court judge agreed.

Just before dawn, New York County Supreme Court Justice Lucy Billings had issued a temporary restraining order barring the police from evicting further demonstrators or from prohibiting those already evicted from returning to the park with tents and sleeping gear. But that order was dissolved late this afternoon by Judge Michael Stallman, who found the prohibition on the erection of structures and tents, and other rules imposed on the use of Zuccotti Park by its owner, Brookfield Properties, were legitimate time, place, and manner restrictions.

Judge Stallman had less than four hours in which to weigh a complex First Amendment dispute on contested facts, so it is not an especially harsh criticism to observe that his conclusion is supported by almost no reasoning at all. And for the demonstrators, there is plenty in the opinion to take issue with. Judge Stallman conceded that the rules adopted by Brookfield were not put in place until after the Occupy movement had begun, which in itself raises serious questions of pretext, and concerns about whether the rules were adopted—43 years after the park was first dedicated to public use—to stifle the message, or the messengers, assembled near One Liberty Plaza.

The court also held that the demonstrators had failed to produce evidence that the rules restricted their First Amendment rights, or were not necessary to preserve the rights of the public generally to use the park safely. But of course the First Amendment ultimately requires the government to defend restrictions on the right of access of a public park, with the benefit of the doubt going to demonstrators.

In the end, the pivotal question will be whether the use of Zuccotti Park—and its sister sites around the country—for semipermanent protests is protected by the First Amendment. That question was not really answered this afternoon, but the prohibition on tents and similar structures suggests the unwillingness of at least one New York County Supreme Court justice to believe that the occupation, as such, can be reconciled with the day-to-day use of a public space.

Opponents of the Zuccotti Park encampment like to point to a 1984 Supreme Court case that upheld a prohibition on sleeping in Lafayette Park, across from the White House, as proof that the First Amendment does not protect sleeping overnight in the national parks out as a form of protest. That analysis was too simple then and is too simple today: For one thing, the regulation sustained in the Clark decision applied throughout the national park system, and was in place before the demonstrators in Lafayette Park bumped up against it. For another, the court upheld the ban on sleeping outdoors in that case based on concerns unique to the parks clustered around the White House.

Occupy Wall Street exists in a First Amendment space all its own. The protestors do not, in an important sense, occupy the spaces in which they exist to the exclusion of other uses, like a rally or a parade. They depend for their rhetorical force not on a temporary massing of thousands, but on the persistent presence, day in and day out, of a committed core of demonstrators, whose ongoing presence extends the teachable moment of their message into a perpetual, if not permanent, opportunity for dialogue. The Occupy movement, in that sense, is a sort of national sit-in, whose continuing presence forces us to confront those questions we would otherwise more easily avoid. The essential moral challenge is the same as that posed by the lunch-counter demonstrators of the civil rights era: We are here, we politely dissent, and we defy you to move us along for your own convenience.

In the end what matters is not whether those demonstrators can sleep in tents, but whether they have the stamina to remain, quiet and unsubdued, in the public space of their choice. If they can do so as winter closes in, in conditions rendered inhospitable by cities intent on forcing them to go, they will have stripped the government of excuses to move them along, and will have created a nonviolent confrontation as worthy of our praise as Selma or the Salt March.

Disclosure: The author has represented members of the Occupy Cleveland movement in federal court. Nothing in this essay relates to that action.