Portraits of Civil War Soldiers

-

Liljenquist Family Collection, Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress.

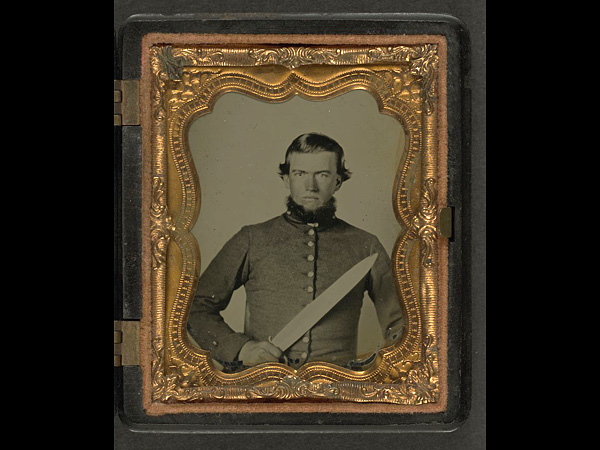

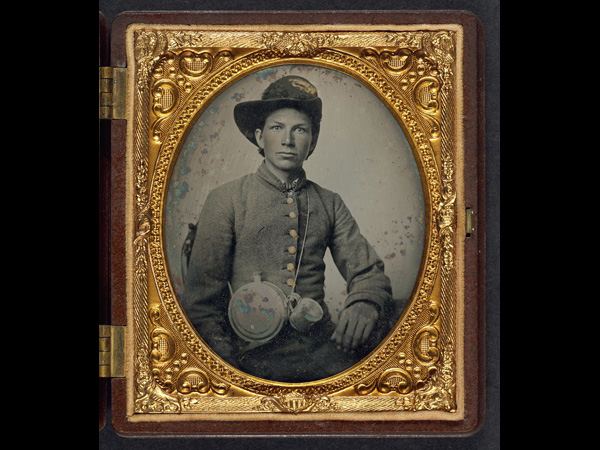

Liljenquist Family Collection, Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress.Unidentified Confederate soldier with Bowie knife. “There are very few details to distinguish the Confederates from the Union soldiers in many of these photographs, which bespeaks how they really were from the same country, the same culture. But one of the differences that you do find is the more makeshift appearance to the Confederates. Their uniforms are much less standard—they’re often wearing bits and pieces of cast-off Union Army uniforms. And even the weaponry is in some cases sort of homemade. One thing that’s particular to the Confederates is these huge Bowie knives, which were humorously called ‘Arkansas toothpicks,’ and they were made often just by local village blacksmiths, because there was a real shortage of weaponry in the South. They became symbols of a particular kind of Southern violence and aggression, and a very personal animus that many Southerners bore against the Northerners that you didn’t find so much with the Northerners against the Southerners. In the early part of the war, Northerners would talk about trying to reunite the estranged brethren. They would talk about hanging Jefferson Davis for treason, but they didn’t talk a lot about slaughtering individual rebels. The Confederates used incredible rhetoric from the beginning. Barely after Fort Sumter, a Virginian writes, ‘Let them come, these minions of the North, we’ll meet them in a way they least expect, we will glut our carrion crows with their beastly carcasses. Yes, from the peaks of the Blue Ridge to the Tidewater we will strew our plains and leave their bleaching bones to enrich our soil.’”

-

Liljenquist Family Collection, Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress.

Liljenquist Family Collection, Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress.Black soldier with revolver and rifle, cannon, and American flag. “When I see the shiny brass buttons on his uniform, which have been touched up afterwards with gold paint by the photographer, I think of a famous remark that Frederick Douglass made about how once a black man wears a uniform with brass buttons that say “U.S.” and carries a musket, ‘there is no power on earth that can deny that he has earned the right to citizenship.’ There’s a sense here of African-Americans as fully becoming Americans, fully embracing their Americanness, in a way that actually surprised a lot of white Americans. A lot of white Americans thought that if the slaves were freed they would immediately rise up and massacre their masters. But they found that black people simply wanted to be Americans like everyone else, and that they were even ready to lay down their lives for their new country. That was in itself an enormous revolution.”

-

Liljenquist Family Collection, Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress.

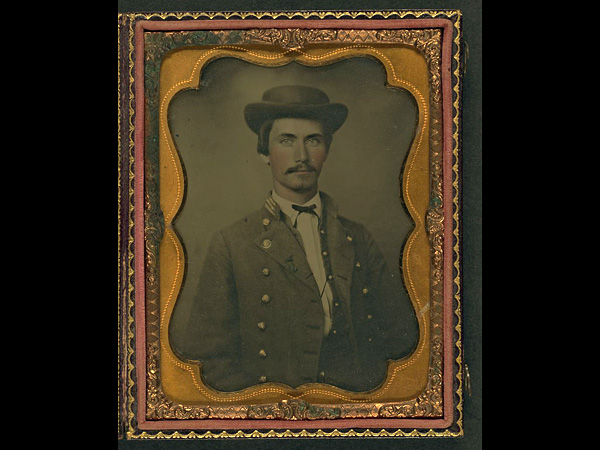

Liljenquist Family Collection, Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress.Captain Jesse Sharpe Barnes, 4th North Carolina Infantry. (He was unidentified until a few weeks ago, when someone looking at the exhibition’s Flickr page recognized him). “With these pictures there’s a sense of melancholy that comes from the fact that most of them were discovered on eBay or at auctions. In a sense, they’re orphaned ancestors. They’re people who have been detached from their own family histories. But here’s the miracle of the Internet that lets us reconnect with them. And there are things about the Internet and digital technology that let us appreciate these images in a way that we couldn’t before. When 19th-century photographs are reproduced in books, you lose so much detail. Now when you can blow them up digitally, you can zoom in on this guy’s buttons, on the whiskers on his chin, and it’s like you’re stepping inside this vanished moment.”

-

Liljenquist Family Collection, Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress.

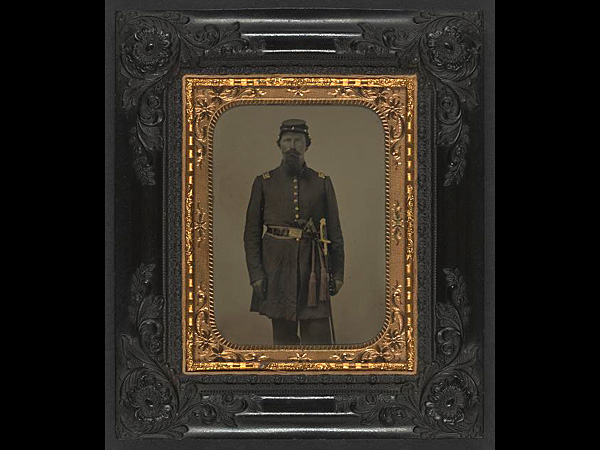

Liljenquist Family Collection, Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress.Unidentified soldier in Union captain’s frock coat and officer’s sash. “When you look at pictures of the men who fought in the Revolutionary War, they’re all clean-shaven. And then you get to the Civil War, and suddenly all these guys sprout this incredible profusion of facial hair. The historians who have considered this always say that it had to do with the fact that it was just too difficult to shave when you were out in the field. But I didn’t buy that, and when I started investigating, I found out that actually, it started in the 1850s, just before the Civil War. In fact, before the war, a reporter strolled through the streets of Boston and did an informal beard survey, of about 800 men, and he found that all but a handful had some sort of facial hair. Facial hair was associated with a few things: It was associated with a new idea of manliness. It was associated with new ideas about religion, a new passion for Old Testament religion and a sense that you were stepping back into the righteous days of the Hebrew prophets. It was associated also with militarism, because it really became popular in Anglo-American culture after the Crimean War. And finally, and I think most interestingly, it was identified with radical nationalist politics in Europe. Beards really took off in places like France, Italy, and Austria, that were undergoing liberal revolutions. I think it bespeaks a sense that both the Union and Confederate soldiers felt that they were nationalist revolutionaries.”

-

Liljenquist Family Collection, Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress.

Liljenquist Family Collection, Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress.Private Albert F. Davis of Company K, 6th New Hampshire Infantry Regiment. “Most people today, if they’d enrolled as a soldier in the Civil War, would have been defeated before they even reached the battlefield, simply by the amount of gear they would have had to carry. A Union soldier on the march had to carry at least 40 pounds on his back, and of course this was in an era before Timberland boots or anything like that, so they’re marching in these mass-produced, ill-fitting leather shoes. And sometimes even, especially in the Confederacy, without shoes at all, which is incredibly hard to believe. These men were made of pretty sturdy stuff.”

-

Liljenquist Family Collection, Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress.

Liljenquist Family Collection, Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress.Unidentified African-American soldier with wife and two daughters. “We don’t know whether this family had been slaves or whether they were free and from the North. But one story that’s been lost from Civil War history is the degree to which black Americans participated as combatants in the war—even the civilians, in a sense. Starting from the very first weeks of the war, there are accounts of black Americans in slavery resisting and even rising up, burning their masters’ houses, running away, and undermining the Confederacy from within. This man is wearing a Lincoln campaign button at a time before blacks were even able to cast a vote in most of the country. It shows the eagerness to participate fully in the political process—something that they would only win (in many cases fleetingly) after the war.”

-

Liljenquist Family Collection, Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress.

Liljenquist Family Collection, Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress.Elias Teeple in Union uniform with saber and revolver. “The early 1860s were a moment when the medieval brushed up against the modern. It’s remarkable to think that even as military engineers were developing long-range artillery that could hit a target from five miles away, ordinary soldiers were still going into battle with swords for hand-to-hand combat, the way they would have done in ancient Greece and Rome.”

-

Liljenquist Family Collection, Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress.

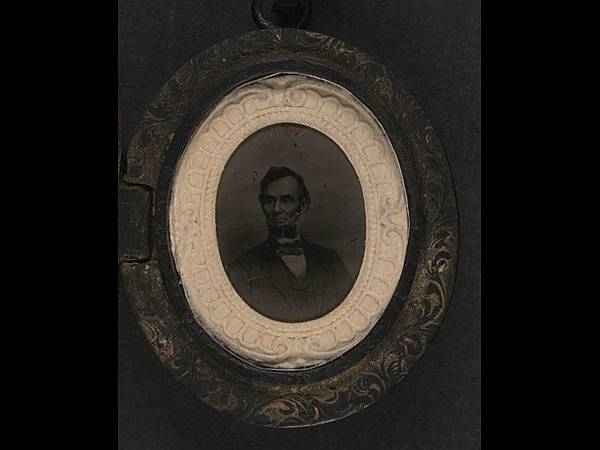

Liljenquist Family Collection, Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress.Abraham Lincoln. “Lincoln was far more photographed than any previous president, and he was far more photographed starting even before he became president. It is amazing just how different he looked from every president who came before him. We look at these pictures today, we think that they all look like stiff, dead, 19th-century guys. But when we look at Lincoln’s predecessors, they’re sitting up very stiffly and they’re wearing high, tight collars. Lincoln wears these low, soft collars. There’s a sense that there was a new informality, that he was from the West. It’s something we’ve seen in more recent times, when we think about John F. Kennedy not wearing hats and looking so youthful after Eisenhower, or Obama looking different from those who came before.”

-

Liljenquist Family Collection, Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress.

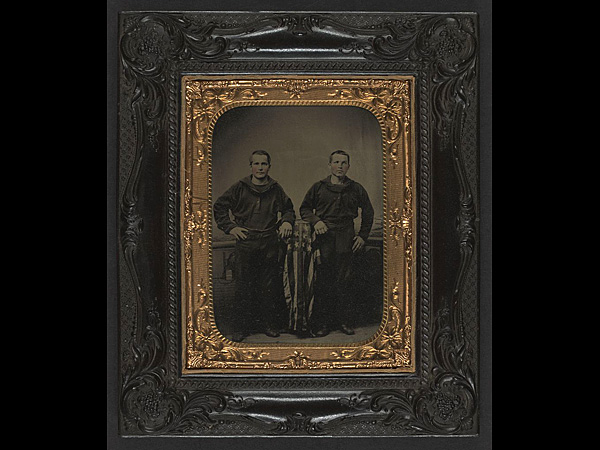

Liljenquist Family Collection, Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress.Two unidentified Union soldiers holding arms. “People today often get disoriented by the intensity of male friendship in the mid-19th century. It was a Whitman-esque moment of romantic passion between men, and you find that notably in images like this. One of the characters I became fascinated with in my book was future President James Garfield, whom I took as sort of a typical young man of that era. He wrote amazing letters to a male friend where he talks about wanting to lie in bed in each other’s arms for a long night without speaking a word except that language that breathes from heart to heart. The significance of this in the Civil War context is that it made these young men ready to go off and fight for the lives of their comrades in battle.”

-

Liljenquist Family Collection, Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress.

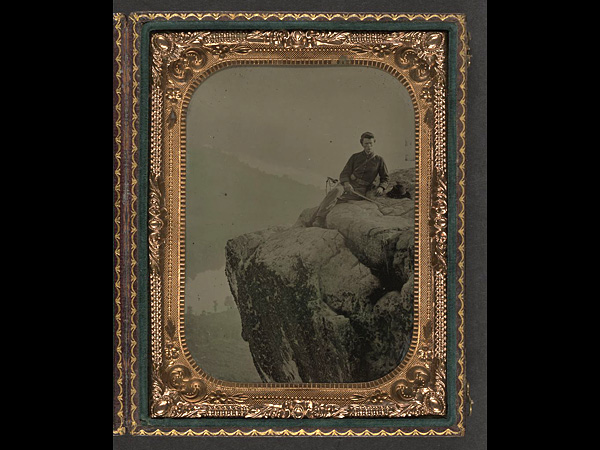

Liljenquist Family Collection, Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress.Unidentified soldier in Union officer’s uniform at Point Lookout, Tenn. “This to me is the most beautiful image in the entire collection. He’s atop Lookout Mountain. He’s a cavalryman. It reminds me actually of images from Romantic painting of the 19th century, like Caspar David Friedrich’s ‘Wanderer above the Sea of Fog.’”

-

Liljenquist Family Collection, Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress.

Liljenquist Family Collection, Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress.Unidentified Union sailors with American flag in front of a painted backdrop. “The Civil War was when the American flag became the common property of ordinary citizens, in a way that it never had been before. Before the war, flags were mainly just used as markers of federal property like forts and ships and embassies. Even before the first shots of the war were fired, flags were everywhere, flying from ordinary Americans’ front porches and shop windows and along the streets. Right at the beginning of the Civil War was when American flags were mass-produced for the first time.”

-

Liljenquist Family Collection, Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress.

Liljenquist Family Collection, Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress.Unidentified young soldier in Confederate shell jacket. “These photos are tiny jewellike objects in gold frames. We can see they were treasured in a way that we don’t treasure individual photographs today. And simply putting ordinary people inside that ornateness is something that was in itself kind of a revolution. The Civil War was the first conflict where there was really a sense, even, of the common soldier as an individual worth being recognized. In the earlier American wars, even in the Mexican War 12 years before, ordinary soldiers were almost never singled out for any kind of distinction. Lincoln instituted the Congressional Medal of Honor, which was presented to more than 1,000 ordinary soldiers in the Civil War. The nobility of the common soldier was recognized for the first time in American warfare.”

-

Liljenquist Family Collection, Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress.

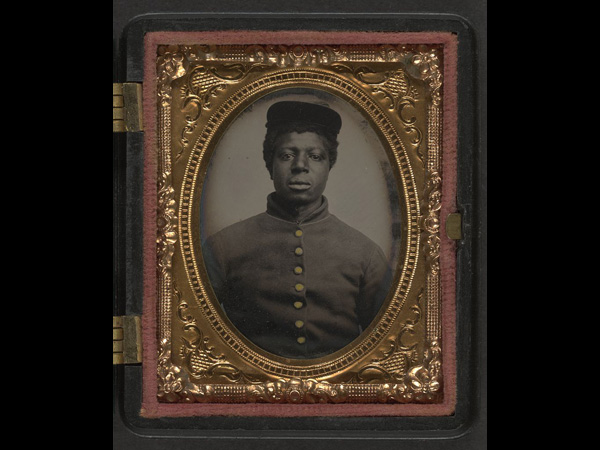

Liljenquist Family Collection, Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress.Unidentified young African-American soldier in Union uniform. “When I came across this image, I downloaded it onto my desktop and just kept looking at it because I found it so haunting. We don’t know the name of this soldier, but the sense of his individuality comes through strongly. It’s hard for us to realize just how novel a thing it was for white Americans to get a sense of black individuality. The white Union soldiers who went down South were so used to thinking about blacks in the abstract, as a mass of undifferentiated people. Then here they were, side by side with these men who were their comrades in arms, and suddenly learning to appreciate their humanity, hearing their stories. And it’s also a particularly powerful image because very few individual firsthand accounts of African American soldiers’ experiences survive. Their literacy rates were quite low. Their families were more likely to be poor, and poor families saved fewer things, so letters and diaries and photographs were much more likely to disappear. So this picture is an especially stirring fragment of one man’s Civil War story.”

This slide show originally appeared with the article Stunning Photographs of Civil War Soldiers: 1861 author Adam Goodheart discusses an amazing new exhibition and his book about the start of the Civil War.