K Troop

The story of the eradication of the original Ku Klux Klan.

Lisa Larson-Walker

1.

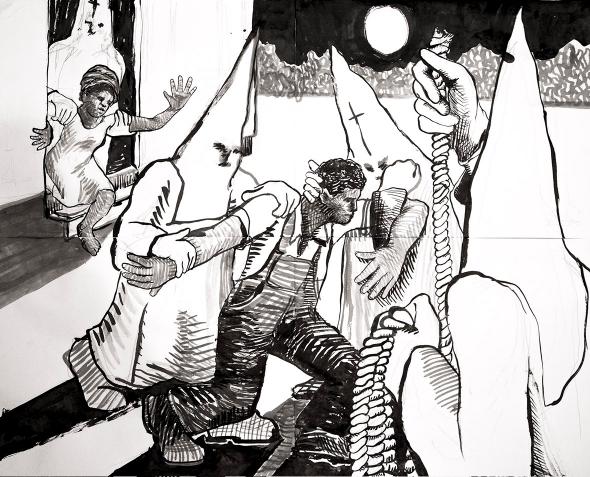

Sometime after 2 o’clock in the morning, the men cramming into the small cabin lowered themselves to the floor. For a passing moment, they must have looked as though they were conducting a group prayer. They were listening at the floorboards for any rustling, breathing, maybe even whispered pleas for deliverance. Then they tore up the planks. A woman standing near them begged them to stop. Ferociously, they went on, until the floor surrendered its secret.

Earlier that same night, March 6, 1871, the Ku Klux Klan had swarmed the South Carolina upcountry. The rumble of 50-odd men on horseback sounded like an invading force. Membership in the local dens of the Klan, which emerged as a paramilitary terror group after the South’s defeat in the Civil War, thrived in York County. But movements like the Ku Klux Klan feed on fear even in times of strength, and the alarms were ringing out over the growing numbers of black voters in local elections.

That night, the riders went house to house dragging black men out of their beds and forcing them to swear never to vote for “radical” candidates—in other words, those set on protecting their tenuous new rights. The Klansmen’s goals went beyond the vote to the humiliation of these men in front of their families, sending the message that whatever else might have changed since the Civil War, the power dynamic in York County had not. “God damn you,” one Klansman cried out during an attack. “I’ll let you know who is in command now.”

The tormenters concealed themselves beneath robes and horned masks; some of the clothing was dark, some white, some bore crosses or grotesque designs. The man leading this night’s havoc was Dr. J. Rufus Bratton. One local resident and former slave later remembered Bratton as a man who set the “style of polite living” around York County. A father of seven who volunteered to serve as an army surgeon for the Confederacy during the war, Dr. Bratton was the county’s leading physician as well as one of the top officials in its Klan. He brought an agenda with him that night that he shared with only a select number of the other nightriders, a term the press began to apply to the violent men.

Bratton claimed a local black militia led by a man named James Williams was responsible for a rash of fires at white-owned properties. These militiamen, supported by the state and federal governments in an effort to encourage black civic engagement, were not content with a ceremonial status. They swore to avenge the Klan’s growing list of misdeeds and murders, to become a kind of counter-Klan force. During the course of the ride, Bratton rendezvoused with younger members of his order, including Amos and Chambers Brown, sons of a former magistrate, and the four Sherer brothers, who were only formally initiated into the Klan during that night’s ride. When the men met up, they used code words confirming their membership.

“Who comes there?”

“Friends.”

“Friends to whom?”

“Friends to our country.”

Bratton directed this smaller unit of men to the home of Andy Timons, a member of Williams’s militia.

Timons woke to shouts. “Here we come, right from hell!” They demanded the door be opened. Before Timons had a chance to reach it, they broke it from the hinges and grabbed him. “We want to see your captain tonight.”

After beating Timons until he gave up the location of Williams’ home, about a dozen Klansmen rode in that direction. They picked up yet another member of the black militia on their way there; even with the information on Williams’ whereabouts obtained from Timons they needed more help to locate a rural cabin in the dead of night. “We are going to kill Jim Williams,” they told their new guide.

Williams’ offenses in the eyes of Bratton and his co-conspirators predated the formation of the militia. During the Civil War, Williams had been a slave near Brattonsville (a plantation named for Dr. Bratton’s ancestors, and where Bratton himself was born) until he escaped from his master and crossed into the North to fight for the Union army. When he returned to York County after the South’s defeat a free man, he represented an era of new beginnings, “a leading radical amongst the niggers,” as one Klansman groused. He changed his name from Rainey, the name of his former owners, to Williams and headed the militia that vowed to check the Klan’s power.

A few hundred yards from Williams’ house, Bratton brought a smaller detachment of his men to the door. Rose Williams answered, informing them her husband had gone out and she did not know where he was. Searching the house, they only found the Williams children and another man. The raid’s leader was not satisfied that his prize for the night was gone and studied the house with his piercing black eyes.

“He might be under there,” Bratton said of some wood flooring that caught his eye.

They lowered themselves, trying for the most likely spot. Prying up the planks, they found Jim Williams crouched beneath.

Rose pleaded with them not to hurt her husband. They told her to go to bed with her children and marched Williams out of the house. Andy Timons, meanwhile, scrambled to gather the militia to warn Williams, but the Klan’s head start was too great. Bratton had brought a rope with him from town and placed it around Williams’ neck as the group selected a pine tree they decided “was the place to finish the job.” Williams agreed to climb up by his own power to the branch from which they would drop him, but when they were ready to finish the job, he grabbed onto a tree limb and would not let go. One of Bratton’s subordinates, Bob Caldwell, hacked at Williams’ fingers with a knife until he dropped.

Searching the woods later, Timons and Rose found him hanging by the neck. A card on the corpse mocked the militia: Jim Williams on his big muster. Meanwhile, Dr. Bratton rejoined the larger group of Klan riders, who stopped for refreshments at the home of Bratton’s brother, John. One of the Klansmen who had not been on the raid asked where Williams was.

“He is in hell I expect,” replied Bratton.

At Bratton’s brother’s house the secret riders could relax without their disguises, revealing some of the most recognizable and distinguished faces of York County. They could celebrate weakening the will and abilities of their local political enemies through their latest campaign of intimidation. But their actions under the cover of darkness that night—and on many other nights filled with whippings, beatings, sexual assault, and murders—were set to unleash an unprecedented counterattack from the federal government with a single goal: to wipe out the KKK.

2.

The Klan’s crimes across the interior of South Carolina reached their saturation point around the time of Williams’ murder. His was just one of many black bodies recovered in the Klan hotbeds of York County (remains were still being found in the area 20 years later). Gov. Robert Scott, a veteran of the Union Army who moved south to aid Reconstruction efforts, pleaded for federal help. The Ku Klux Klan may have seemed merely a ghoulish attempt to scare people when it first spread from its founding chapter in Tennessee in 1865, but Scott contended it became “a terrible fact, an armed organization, thoroughly equipped, having its field, staff and line officers, and established lines of communication.” There was a war on, this time with only one side fighting.

Scott extracted promises of peace from local white power brokers with Klan ties only to watch violence resume. He could not call on state militias because they’d been disbanded for the safety of the militiamen; the so-called Kukluxers had outgunned them. In fact, the closest thing to a working militia in South Carolina was the Klan itself. The seriousness of the problem became impossible to avoid, working its way to President Ulysses S. Grant. Grant promised “prompt and decisive” federal action to a visiting delegation from South Carolina. Strategists at the War Department, the forerunner of the Department of Defense, began to rearrange their map of United States Army regiments to free up forces and zeroed in on a battle-tested officer named Lewis Merrill to lead the unusual engagement.

Maj. Merrill, having drawn the assignment, had to confess he had doubts about the stories he’d heard of Ku Klux Klan dominance in South Carolina. “Let me put it stronger even than that,” Merrill said when recalling his thoughts upon receiving his next post while stationed in Kansas. “I was absolutely incredulous.” His superior officer warned him that the reality of the Klan’s terrorism was worse than rumors could convey. Whatever else he thought he might be up against, the 36-year-old Maj. Merrill could never imagine how this mission would reshape his life and legacy.

The West Point–trained Merrill, who attracted strong acolytes and stronger enemies, had been promoted while in the Union Army until he was commanding his own unit. His cavalry regiment in the Civil War, taking on the identity of its headstrong leader, became known simply as “Merrill’s horse.” Raised in Pennsylvania in a family filled with lawyers, including his Dartmouth-educated father, Merrill felt many of that profession’s skills of methodical analysis and procedure had been passed down to him, and he showed them off as a military inspector general and judge advocate in courts-martial. He had an imposing build and youthful face. A New-York Tribune reporter mused that he looked like a German professor, probably from the air of blunt intensity that can be detected in surviving photographs of him. Merrill ranked as a top officer in the 7th Cavalry by the time he headed for South Carolina.

Maj. Merrill was something of a specialist in handling elusive dangers and sensitive dynamics. During the war, he had taken on guerrillas in Missouri who stalked Union soldiers, and then faced Confederate troops hidden in the woods in Arkansas in the Battle of Bayou Fourche. In postwar Kansas, he had been charged with the tricky job of clearing up a conflict over territory between the Miami tribe of Native Americans and white settlers—with his original mandate being to remove all the whites. As the slow, rickety train carrying his men—made up mostly of Troop K of the 7th Cavalry—traveled through the interior of South Carolina, Merrill contemplated how soldiers coming from outside state lines could address a problem of locals terrorizing locals.

K Troop did not arrive in York County quietly. They marched all day on foot and horseback 22 miles from the Chester railroad station and reached Yorkville around 9 o’clock the night of March 26, 1871; in addition to the 60 horses with the 90-odd men, the officers’ pampered dogs strutted through the streets. The entrance of the troop was announced in the newspapers and spoken of on the long front porches of shops and houses. The high society ladies of Yorkville paid visits to Merrill’s wife, Anna, who had come along with other officers’ wives.

Merrill immediately organized open meetings where community leaders turned out in force to hear his exhortations for their assistance. He was, as usual, direct and to the point. His purpose was “to preserve public order so far as lies in my power.” The obvious and most painless solution was to enlist the reasonable white citizens to put an end to disturbances by the misguided and disgruntled among them. The county leaders promised to use their influence to do just that. They circulated and signed petitions to the same effect and published them in the newspapers.

One of the most vocal of these boosters for Merrill’s cause was a tall, slender gentleman with an unassuming, even kindly demeanor: Dr. Rufus Bratton. The same man who fitted the rope around Jim Williams’ neck.

* * *

The name of the organization Merrill faced in York derived from the Greek kyklos for “circle” and the Scottish-Gaelic clan. The clan aspect emphasized the quasi-familial relationships promised by the order in a postwar South where many actual families were reduced in size or strength. It was a circle in the sense of a society or group but also its insularity and isolation. Klan rules managed to keep identities and plans secret even within the order, with members only referred to by numbers while involved in their operations. Contact was deliberately limited between one den and another or between subordinates and higher officers.

Klan operatives carefully monitored incoming intelligence on the efforts against them. In fact, before K Troop made the long trip from Kansas, a different squadron of U. S. Army soldiers headed for York County to prevent a Klan scheme to attack the county treasurer’s office. The Klan tore up the railroad tracks in advance to stop the infantry’s arrival. While the soldiers labored to repair the tracks, the Klan carried out its raid on the treasury—which targeted the white treasurer whom the Klan believed supported the black militia. The treasurer, knowing the Klan wanted him dead, fled not just the county, but the country, ending up in Canada.

K Troop’s operation was no simple protective detail, and ripping out a few tracks wouldn’t have stopped them. The Klan leaders met with a lawyer who advised them on the best strategies to avoid trouble. The brain trust ordered its members to smile and extend their hands in friendship. By putting some of the major Klansmen front and center to promise their support, they were, in essence, rendering themselves invisible. Bratton and the other Klan leaders hoped they could distract the newcomer Merrill with cooperation long enough that he would report back that panic about the Klan was unwarranted. In this scenario, K Troop would be ordered back sooner or later to more significant places of engagement, handing the secret paramilitary organization, in Merrill’s later words, “the whole game in their own hands.”

Merrill did report to his superiors that the assignment looked like a quick one. But even with a naturally trusting personality, he knew better than to rely on appearances. One recurring comment from the supposedly supportive community leaders particularly jarred Merrill. He heard it from almost every prominent citizen up and down Congress Street. After promises to help stop the outrageous Klan, people would add some variation of: “But you cannot but acknowledge that they have done some good.” It was as though they couldn’t help themselves.

Yorkville was a quaint town with a respectably bustling commercial center, but the area had struggled with a farm economy hit by higher-than-average rates of casualties during the war as well as by the transition away from slave labor. When paying wages to his former slaves no longer made financial sense on his farmland, Dr. Bratton cut ties and gave them the ominous direction to “go their way with their freedom either in peace or misery.” The hardships heightened many white citizens’ anger over the perceived intrusion of Northern values that produced “radical” empowerment of the large local black community. The ingredients proved a powerful breeding ground for Klan membership.

“The cause of Ku-Kluxism,” Merrill reported to Congress, “lies in the dissatisfaction of the white leaders with the results of the war, and in their determination to nullify these ... to make salvage of the wreck of the rebellion.” This chimes with Bratton’s private thoughts. He reflected in his diary on the experience of abandoning a Confederate hospital out of concern it could be targeted by the Union Army: “I prayed that the day of retribution would soon come when justice long withheld should be meted out to these ruthless invaders of our Country.” Later, Bratton had sheltered Jefferson Davis during the Confederate president’s flight from capture. Davis left him with words of advice: “Do not expect anything just or right from the abolition Yankee. They will never grant you our rights.”

It was now six years since Appomattox, but evidence of the war’s aftermath was everywhere. Sgt. Winfield Scott Harvey, the blacksmith of K Troop, kept track of the battlefields they passed on their trip by boat and train from Kansas to York. Burned mansions still dotted the landscape. Many Southern whites stewed with anger at their defeat and humiliation at the hands of the Union Army and the continued degradation through Reconstruction efforts of their perceived birthrights of racial and economic superiority. Their black neighbors were daily reminders of all they had lost beyond battles. If a ghost war was to be carried out, blacks were the proxies for the North and the Klan were the ghost soldiers, right down to their flowing robes and masks.

Merrill collected details of heart-breaking murders like that of Jim Williams and the myriad instances of whippings and beatings. The municipal authorities rarely acted in any of these cases. The difficulty of inquiring into these crimes started with the anonymity the Klan achieved through its disguises, but that was only the beginning. Even when Klansmen were recognized by their voices or horses, or a mask torn away, witnesses remained “terror-struck” and were sometimes targeted by the Klan to make certain they wouldn’t testify. When one black witness to a murder told the coroner he feared for his life if he reported what he knew, the coroner laughed and the other white men in the room, including members of the coroner’s jury, nudged each other.

Merrill, using the methodical skills he’d proudly displayed in his judicial roles in courts-martial, cross-referenced the records of the county clerks, the coroner’s office, and the courts to piece together an improvised evidence locker for the Klan’s crime waves. He even requisitioned the sign pinned to Jim Williams’ dead body to analyze the handwriting. Merrill scrawled detailed notes in his rushed but precise script on a growing pile of loose scraps of paper. He discovered with his own eyes the spell of terror around the county. Black men could be found sleeping in the woods at night instead of in their houses, in fear of being dragged from their beds; at the same time, those taking shelter in the woods worried about what could happen to their wives and other family members left alone. Klansmen raped and sexually assaulted black women both for pleasure and retaliation.

Lisa Larson-Walker

The more Merrill learned, the more determined he became. He was uncompromising about his responsibilities and about holding other people to theirs. When Merrill trained at West Point, he served on sentry duty when a fellow cadet was caught hazing another cadet. The perpetrator began to flee and ignored Merrill’s orders to halt. Merrill stabbed his classmate with his bayonet, sending him to the hospital with a flesh wound.

Merrill spread the word around York County that he offered sanctuary to those who feared the Klan. Quietly, he gathered informants. He astutely recognized how even though the Klan and its enablers were “fully convinced that because the negroes do not show any signs of resistance they are completely cowed,” that, in fact, “this is far from the truth.” Whether they had tried to resist by force or through the law, the system was against them. Now the citizens could fight back by helping Merrill.

One of those citizens was an extraordinarily brave black farmer—Merrill protected his name so well that to this day it is not to be found in the surviving records. The Klan compelled this man to assist them, presumably to carry out errands and perhaps to provide them information on other blacks. In return, they would not drive him from his home and destroy his crops. Caught in this awful vise, the farmer now had another path. He became one of Merrill’s most valuable spies.

Merrill’s confidential notes became detailed documentation—the first of its kind—of the Klan culture, its sacred oaths, and its secret code words and signals designed to allow members of the order to communicate covertly. In addition to the “friends to our country” salute exchanged on the way to the Klan’s lynching of Jim Williams, if an officer of the Klan needed proof of another officer’s status, he would ask, “Are you a Ku Klux?” The response that would confirm it was “I am not.”

As the hot and rainy spring progressed, Dr. Bratton and the other Klan officers, including wealthy merchant James Avery who earned the Klan’s title “Grand Giant” (head of a county), had more reason to worry. Merrill made clear in his public meetings that he would dismantle the Ku Klux Klan, and he looked to be in no rush to bring K Troop out of Yorkville. They had settled in at the Rose Hotel on Congress Street, an especial affront to Bratton—he and a business partner built the hotel, and Bratton’s house sat next door. One of Bratton’s vivid memories from his time as a Confederate surgeon was staying up one summer night in 1863 caring for 30 wounded men fighting for their lives in a makeshift hospital, with only one other doctor to help him. Now he had to watch day after day as blue-coated soldiers, some of whom may have fired the bullets that had forced him to carry out endless gruesome amputations that “gloomy, weary” July night during the war, milled about in the comforts of his building.

The Klan’s foot soldiers grumbled at commands from on high to keep a low profile in order to wait out Merrill’s stay; their mandate was to prevent the growing influence and independence of the black population—by preventing black voting, blacks holding office, blacks arming themselves—and sitting around would ensure their gains would erode. It would only be a matter of time before Klansmen would take up arms again, with K Troop added to their target list.

3.

Nighttime raids against blacks who were causing real or imaginary problems for the Klan resumed within weeks of K Troop’s arrival. One of those considered a threat was a 52-year-old preacher named Elias Hill, as much a warrior in this fight as Merrill and his heavily armed soldiers. Hill’s body was dwarfish and his limbs drawn, as he put it, “out of all human shape.” His condition first revealed itself when he was a young slave, then attributed to “rheumatism” and believed by some modern scholars to have been muscular dystrophy.

Hill was a brilliant autodidact, a schoolteacher and preacher. He was, as far as Merrill understood, one of only two blacks in York County who could write (some of the children of his former owner helped teach him when he was a child). Despite his physical frailty, his intelligence and influence made him an enemy to the Klan.

On May 5, 1871, Klansmen burst into his cabin and dragged him from his bed by straps they wrapped around his feeble neck. They threw him onto the muddy ground, beat him, and forced him to admit—though he couldn’t walk or even crawl—to starting fires that had supposedly plagued white-owned properties. They also forced him to renounce support for Republican politics and to swear to publish a statement to that effect in the newspaper. Bizarrely, they made him promise he would cancel his subscription to a certain newspaper they found politically offensive. They pulled at his deformed and contracted legs and pointed pistols at his head. They asked him if he was ready to die. The Rev. Hill told them with a composure that likely made his tormenters angrier that he was not quite ready to die and that he would rather live. Threatening to toss him into the river, they accused him of having supported Jim Williams before he was hanged and of having corresponded with Rep. Alexander Wallace.

Hill survived. His sister-in-law and mother were beaten the same night. Klansmen found and burned the letters between Hill and Wallace and while some of the attackers began breaking up furniture, Hill could hear a conspicuously well-spoken Klansman chastise the others, encapsulating a social divide within the Klan: “Don’t break any private property, gentlemen, if you please. We have got what we came for.” The importance of the letters between Wallace and Hill to the attackers is telling. The Klan leadership despised the pro-Reconstruction Wallace and might well have concluded that the articulate and influential preacher’s letters to the congressman played a part in leading the War Department to initiate the occupation of Yorkville, their county seat, by Merrill.

Hill was in so much pain he could hardly speak, but in a remarkable finish to the outrages, the assailants forced the preacher to pray. “Don’t you pray against Ku-Klux,” he was ordered from under one of the hoods, “but pray that God may forgive Ku-Klux. Don’t pray against us. Pray that God may bless and save us.” A Klansman gave him back one of his books before leaving and, Hill later recounted, momentarily “forgot to speak in that outlandish tone that they use to disguise their voices.” Between the costumes and their voices, the Klan’s activities were deliberately performative, carefully designed to convince victims that the Klansmen were nobody and everybody, that there was no escaping them. Though the masked attackers promised to come back and finish him off if he disobeyed their commands, when he regained strength, Hill—in an incredibly courageous act—wrote a letter to Merrill detailing the assault.

Blacks were also sneaking into Merrill’s headquarters at night to relay stories to him and identify members of the Klan. As in the example of the Rev. Hill, their bravery in putting their lives and their families’ lives at risk by going to Merrill cannot be overstated. One woman whom the Klan beat—and whose child was beaten in front of her—was promised there would be further violence if she ever told Merrill, which she promptly did. Only through the heroism of these men and women could Merrill obtain the evidence and inside information he would need. Merrill tallied 11 murders in the county for 1870 and the first half of 1871 alone, forcing him to severely revise his original outlook. “The prospect of a peaceable future here,” he said, “is gloomy.” He sent troops riding at night as a kind of patrol around Clay Hill, the area where many blacks lived and most outrages occurred. But the “Invisible Circle” proved as elusive to catch in the act as that mystical moniker suggested.

When Gov. Scott had requested help from the federal government, he had been confident even the Klan would never go against the United States Army. In addition to Merrill, K Troop boasted formidable veterans of the Union Army. Second in command was Capt. Owen Hale, a descendant of the Revolutionary War hero Nathan Hale. The 28-year-old moved up the ranks rapidly during the Civil War and earned the nickname “Holy Owen,” which has been alternately attributed to his embodiment of the perfect soldier or to his versatile profanity. Ohioan Edward S. Godfrey, 27, entered the infantry in the Civil War a private and served impressively enough to receive a place in West Point, leading to his eventual position as Merrill’s lieutenant.

But Merrill knew the longer he stayed, the higher the likelihood of incidents in this unfamiliar setting. Even the dust in the air made men ill. When one soldier of K Troop, George Whittimore, caught a serious disease and died, he was buried in this land of strangers. Merrill contended with the reluctance of so many white locals to accept the soldiers into their cemeteries—even in death they remained invaders.

An unusual number of Merrill’s soldiers fell from the hotel’s windows, including one who died from his injuries. Merrill was suspicious about the casualties, dryly noting “nothing remarkable about the placing of the windows which should bring such a result.” Drunkenness and clumsiness might have been the only culprits for the falls, but Dr. Bratton’s knowledge and access to the hotel undeniably provided opportunity for structural sabotage. Desertion also became a damaging and atypical problem. Merrill reported back that the “desertions are encouraged and facilitated by Ku Klux and their sympathizers.” In one instance, Klansmen provided deserters with horses and escorted them to the railroad station. In addition to depleting Merrill’s resources, the desertions gave ammunition to the Klan for a propaganda war, feeding details to the press to portray Merrill as an unfit commander.

The York County sheriff made his eagerness to help clear upon Merrill’s arrival, so Merrill arranged joint patrols to look for Klan marauders and agreed to Capt. Hale being appointed a special deputy. Merrill explained to Sheriff R.H. Glenn that he was setting up a stakeout for one of the Klan squads to catch them during the commission of a crime. The squad was warned at the last minute and avoided the supposed trap. In fact, Merrill’s gambit had not been a trap for the Klan at all; it had been a mole hunt. Sheriff Glenn was the only person who could have warned the Klan, and he had exposed his allegiances.

Merrill also suspected the Klan had been going through his private papers. He used the same office in the Rose Hotel formerly used by the ex-country treasurer who had been driven to flee to Canada. Merrill left bait in his office in the form of a pencil memorandum about the Klan. The bait disappeared from his desk. In an example of Merrill’s cunning humor, the faux memoranda apparently warned the Klan that Merrill was coming after them.

* * *

As the hot summer air mixed with light rains coming from the coast, a new plot brewed from the Klan side of the chess game—a brazen plan to attack Merrill’s troops.

The Rose Hotel housing K Troop was a brick building on the main street in Yorkville; there was an adjacent stable where the horses were kept and white tents on open ground set up for the guards. Merrill’s men were in the center of all things, a constant reminder to the Klan and their victims of their presence—but a security risk to the soldiers themselves.

The unnamed black farmer now serving as Merrill’s best spy first informed him of the details of the plan. A squad of Klansmen would sneak into the back of his camp and fire two or three volleys on the bluecoats before fleeing, with the probable intention of provoking enough of a response back from Merrill’s men to cement the United States Army’s status as villains in the public eye. Merrill himself observed a young man doing reconnaissance for the assault while the soldiers listened to a sermon by a visiting preacher.

Merrill doubled the men posted to the stable. Horses were saddled up and ready. He also doubled the camp guards, pacing with their long Sharps rifles, and placed six men around his own rented house, a two-story structure hugged by oaks and pines, where his wife stayed with his son, 11, and daughters, 9 and 13. He posted what he called “silent sentry” who, if they saw the approaching armed assailants, would signal the rest of the troop but “let them come.”

The next morning, the soldiers drilled in the open for everyone in the town to see. The major also made sure he was easy to locate that day. Attending to some business at the courthouse, Merrill was told there were some men who wanted to see him. He found a delegation of community leaders, several of whom had greeted him upon his arrival to town. They wanted to know about the excitement around his camp. Merrill told them about the Klan’s plan to attack the soldiers and the men pushed for more. They demanded to know the names of the alleged assailants so they could help bring them to justice.

Merrill’s maneuvers had been canny. He already had the names of 10 or a dozen Klan members who had planned to carry out the attack. He could have simply sent a detachment of troops to round them up. Alternatively, he could have added protective measures in his camp stealthily. Instead, he’d staged his forces to let the Klan know that he knew they were coming. One of two things would happen. The attackers would “screw their courage to the sticking point” (as Merrill said, absorbing the drama of the moment and quoting Macbeth) and follow through with the attack, at which time Merrill would “gobble them up.” Merrill confessed he was hoping for this scenario because of his “exasperation with their infamously cowardly outrages and with the stolid indifference cowardice and want of capacity, honesty and energy of the civil authorities.” In other words, he wanted the chance for a free shot at them.

Then there was scenario two. If one or more “respectable citizens” came to him asking for information about his informants, he would have good reason to believe they were part of the Klan, and either had been behind the abandoned scheme or were looking to punish a breakaway faction for plotting against orders. Klan members who took the secret oath and then betrayed the Klan were, so the rules stated, sacrificed. Merrill had learned the exact language of the oath:

I do solemnly swear to support and defend and bear true allegiance to the Invisible Circle. ... To keep sacred all the secrets committed to me or that come to my knowledge concerning the invisible circle, and if I fail in my oath or reveal the secrets of the order may I meet the traitor’s doom which is Death! Death! Death!

The delegation of concerned citizens at the impromptu meeting with Merrill in the courthouse pressed for more—who was Merrill’s informant? Merrill had as good as torn the masks off the Ku Klux Klan leadership. He looked into their eyes, so filled with concern for Merrill’s mission of law and order. The eyes of Dr. Rufus Bratton, merchants James Avery and Thomas Graham, Judge Beatty. Merrill said he was not at liberty to give the names of the thwarted assailants or his informants, but he promised the men that the time would come for those who had planned the attack to be punished, and reassured them that he had perfect knowledge of his enemy.

4.

The Klan rank and file weren’t the only ones spoiling for action. Sgt. Harvey couldn’t help feeling disappointment the planned raid against their camp did not happen. “Our Troop laid on their arms ready to receive them,” wrote the blacksmith, “but they are too big of a coward to come.” The solders’ animosities extended toward the people of Yorkville at large. While the Fourth of July found K Troop celebrating with cheers and shouts, the visiting soldiers found the streets eerily quiet. The locals’ anger and suspicion toward the government ran so deep, they refused to honor the holiday.

Merrill assigned spies to shadow all those citizens he now suspected of leading the Klan, including Dr. Bratton. He was making his plans to engage the enemy, but a big step awaited completion: to convince Washington that things were worse than even the most vocal alarmists had claimed. Political opponents of the Klan did their part back in D.C., succeeding in the passage of legislation that allowed the president to call for the dispersal and arrest of the Ku Klux Klan under certain conditions. Merrill had to demonstrate that his mission in York County had produced the proof and justification to put the act into motion.

Merrill realized, more and more, just how surrounded he was. When he telegraphed information back to Washington, Klan members instantly came into possession of the whole exchange—the telegraph operator was part of the Klan. The conductor of the railroad was Klan, too, and spied on the movements of bluecoats delivering messages for Merrill. Along with the already exposed sheriff were judges, lawyers, municipal officials—all loyal members. As one of Merrill’s soldiers commented in a morbid mood, “Go out and shoot every white man you meet, and you will hit a Ku-Klux every time.” Merrill’s knowledge of the Klan’s assortment of signals could make a simple walk down Congress Street a surreal experience—if two men shaking hands interlaced their little fingers and touched the palm with the point of the forefinger, they were Klan; if one man tapped his left ear with his left hand three times, and another walking by then put his right hand in his right pocket, thumb on the outside and fingers on the inside, Klansmen were hailing each other. It was as though the major entered some Poe-inspired gothic tale about a search for a town’s hidden monsters that ended with half the townspeople the monsters.

Lisa Larson-Walker

Merrill’s chance to mobilize the information and intelligence he’d so carefully compiled came with the visit of a four-person delegation from Congress. Reps. Job Stevenson and Philadelphia Van Trump of Ohio, and Sen. John Scott of Pennsylvania were escorted to town by Rep. Wallace from the local district.

Merrill, who kept out of politics whenever possible, dined with the congressmen the evening of their arrival at Rawlinson’s Hotel in the center of town. Publicly showing himself with the delegation reminded the Klan, after their aborted attack on camp, that he still had the federal government’s backing and gave them incentive to stop marauding while they had a choice. Merrill had much to tell the legislators, constituting a subcommittee of a larger body looking into violence in the South.

Merrill described how his original doubts about the Klan’s power had been fully dispelled. Klan violence was everywhere, and York County’s will and ability to act against it was nonexistent. “I never conceived,” Merrill reported bluntly, “of such a state of social disorganization being possible in any civilized community.” A full three-fourths of the white population in the area were part of or enablers of the Ku Klux Klan. In York County, Merrill estimated nearly 2,000 sworn-in members. There were whites who abhorred the Klan’s actions, but they were too frightened to do anything about it—white men had been hanged and had their throats slit for standing up to the order. “Martyrs have always been scarce,” as Merrill put it. One former Klansman who “puked” up information to Merrill (as the Klan put it) was now in hiding under the army’s protection.

A short time into the dinner, a drunken man named James Berry tried to empty a pitcher of cream onto Rep. Wallace, a liberal politician who was caricatured locally as a demonic villain. The hotelkeeper interfered at the last moment and the cream landed on Rep. Stevenson. Berry fortunately had decided against his first choice, hot coffee. Wallace and several other men at the table immediately thrust their hands into their pockets, and there was a palpable tension as onlookers in the restaurant waited for weapons to be drawn, a testament to the general expectation of violence hard-wired into York County. In fact, a drawn pistol was reported in the New York Times, but only handkerchiefs came out of coat pockets.

This rehearsal of violence portended the real thing. As Merrill continued his pivotal meeting with the delegation, a band of black musicians gathered in the pleasant evening air to serenade and celebrate the visitors from Washington. This attracted a crowd of hostile whites around the musicians. As Merrill and the visitors finished dinner, the standoff outside shifted into chaos. A policeman named William Snyder who was jostled by the crowd tried to arrest Tom Johnson, one of the black musicians, for blocking the sidewalk. When Johnson tried to run, the policeman shot him with his pistol at point-blank range.

Merrill was in conversation with Sen. Scott when the shots rang out. After the pistol fired, Merrill’s trained ear could make out the firing of a longer weapon coming from his own sentry shooting into the air to alert the troop. Merrill jumped up and ran. Reaching the center of the melee he found Johnson on the ground, his face covered in blood. In the crowd, the unreal atmosphere of York County revealed itself again. The policeman holding the smoking firearm was Klan. The Yorkville mayor, standing amid the crowd, was also Klan.

Merrill pleaded with the furious black onlookers to disperse from the scene. Having come to trust in Merrill and his mission, they listened. Merrill then demanded the mayor order the white crowd away. Merrill staved off the possibility of more bloodshed or a full-blown riot, and gave enough space for the victim to be treated. Snyder had shot Johnson once in the back through his shoulder, once through his hand, once in the elbow, once in the arm, and once through the face.

The local authorities, predictably, brought no charges against Snyder. Johnson somehow survived his wounds and Merrill’s interview with him added to his voluminous accounts of racial violence in York County. No more morbid demonstration of the Klan’s violent outrages could have been enacted for the members of the subcommittee—not only an unprovoked shooting a few feet from them, but also an understood fact that nothing would be done about it.

Dr. Bratton and Avery feared blowback from the subcommittee’s visit. Klan leaders worried that additional nervous members might spill secrets to the visitors and reminded membership—as if they needed such a reminder—that the punishment was death. Some Klansmen, showing hints of grave concern about what might come next, proposed accosting the congressional visitors and stealing their reports so they could not be returned to Washington, though wiser heads ruled out this plan.

Sen. Scott sent the subcommittee’s reports to Ulysses S. Grant’s summer home in Long Branch, New Jersey. Across the political spectrum some viewed Grant’s enforcement of Reconstruction policies toward the South as overreaching, creating an undercurrent of controversy as he progressed through the third year of his first term. But concerns about a re-election campaign could wait. Grant was alarmed by what he read in Scott’s documents.

The president left the seaside early to assemble his Cabinet at the White House. Armed with the information gathered by Merrill and collected by Scott and his committee, President Grant wanted immediate action. Bureaucracy, however, churned on, with months of further meetings, inquiries, delegations, grand jury investigations, and ever more reports, during which time the Klan continued its rides of terror and beatings, threatened victims if they dared report violence to the “petty despot” Merrill, and tore down the local black schoolhouse for the fourth time. Finally, an order from President Grant reached Merrill to bring in the insurgents—all of them.

5.

Members of the Ku Klux Klan were offered a five-day grace period to turn in their disguises and weapons. There would be no mass public surrender from a society so secretive that members often hid their identities from each other. The White House triggered the next step against York and nearby counties. For the first and last time in the country’s history, the president of the United States suspended habeas corpus—that is, the right of a judicial process for arrest and detention—during peacetime. The region was under martial law.

Investigation and deliberation could be traded for action. K Troop readied. They had been practicing firing newly received rifles into new targets. Merrill’s superior, Gen. Alfred Terry, sent soldiers from the 7th Cavalry’s Troops D and L to supplement K, in addition to Troop C of the 18th Infantry, which had arrived for support. There would be more administrative needs to accompany the military ones. A South Carolina state senator assigned Louis Post, a self-proclaimed “carpetbagger” from the east, to Yorkville to assist as a secretary, and another private secretary, a man named Dick Clinton known for being especially clever, came from the military side.

Merrill’s telegraphic communications with Washington were now transmitted in cipher, with his Washington go-betweens urging Merrill to keep the key to the cipher “in your own custody as its loss, or betrayal would involve the change of the entire system.” They had learned that, in addition to having spies in the telegraph office, the Klan had a machine that could tap the wires to intercept the content of telegraphs. The Shakespeare-quoting Merrill probably never knew, but might have appreciated the fact, that one of the government clerks copying the outgoing confidential letters from the attorney general’s office to K Troop headquarters was 52-year-old poet Walt Whitman.

The time for the next phase couldn’t come soon enough for Merrill. Local blacks grew tired waiting for decisive action from him, and he worried they might suspect that he silently sympathized with the Klan. Survivors of Klan brutality such as the Rev. Elias Hill, even if they trusted Merrill, remained pessimistic that even the U. S. Army could make enough of a difference. In fact, in the same days that Merrill prepared for the most significant military operation of his career, Hill departed from South Carolina with a group of 165 blacks to settle in a recently established colony in Liberia, part of a movement within black America to create a destiny free from racial animus through relocation.

After four years of almost completely uncontested rule in the region, on Oct. 20, 1871, the Ku Klux Klan woke to find the world turned on its head. Merrill split his now 100-plus soldiers into individual posses, led by Lt. Godfrey and Capts. Hale and Thomas Weir, and on his signal they galloped off from the stables of the Rose Hotel in every direction. The Klan’s rides had terrorized their victims by bursting through doors and dragging them out, their fates and futures uncertain. Now they faced a version of the same formula, empowered by the pent-up strength of the 7th Cavalry’s K Troop, with a pointed difference that the troops arrived in broad daylight rather than in darkness. With their specialized training, K Troop had become a kind of operational counter–Ku Klux Klan force of the sort Jim Williams dreamed, down to the coincidental letter K in their name. Spreading out across York that day, the troops, accompanied by specially assigned U.S. Marshals, took in scores of Klansmen almost simultaneously.

The Klansmen had feared the worst and some had been on a sharp lookout for such movements against them. A detachment of troops neared the farm of the Browns. Amos and Chambers Brown, the latter one of the leaders of the local Klan den, had been part of Dr. Bratton’s lynching party of Jim Williams. The brothers, hearing or seeing Merrill’s troops coming, or perhaps hearing a coded warning ring out, fled the house. Left only with the young men’s father, 57-year-old former magistrate Samuel, Merrill ordered the family patriarch held in a nearby barn, where soon enough another half-dozen Klansmen rounded up from the immediate area would also be temporarily stocked.

Merrill thought Samuel could be used as leverage to draw his sons into custody. In fact, Merrill had taken in a bigger prize with Samuel than he knew. Lt. Godfrey found a key on the prisoner, and returning to the Brown homestead, opened a locked desk drawer containing the only copy of the Ku Klux Klan constitution and bylaws found during their raids in the entire Klan-infested county. Brown told an innocuous story of how it came to be in his desk and claimed never to have examined the documents. But as the deepest inside workings of the Klan began to be exposed, Brown’s role as one of its leaders came into focus, with indications he even initiated the members. One member recalled that Samuel Brown boasted that his particular cohort of Klansmen could kill and whip more blacks than the rest in York County combined.

When the soldiers burst into the Sherer’s log house, young John Sherer hid under the bed. Merrill’s men left him alone, knowing exactly whom they were hunting. They rounded up William, James, Hugh, and Sylvanus Sherer, all of whom had been on the midnight ride to kill Williams. One of the most important elements behind the success of the raids, Merrill later recalled, was the Klan members’ surprise about how much Merrill’s men already knew about them—which seemed to the Klansmen a remarkable feat given their pride in their extreme secrecy.

Because of the bravery of Merrill’s informants, his men were also prepared for all the signals and codes the Klansmen used to warn each other as the bluecoats descended on them. When “Ambulance!” was shouted, it was a cry of distress and meant another member was nearby. Likewise, three successive sounds of any kind was another way of warning danger to those nearby. Merrill had even drawn on paper the musical notes of the Klan’s warning whistle.

However well-trained and well-versed in Klan secrets, Merrill’s soldiers could not know all the sources of danger around them. Four young members who fled arrest hid out in the hills with Winchester rifles. Garland Smith, who was involved in the shooting murders of at least two black men, aimed his lever-action rifle from his position above, placing a bluecoat in his line of sight, and prepared to shoot, until his companions restrained him.

As the number of arrests grew, astounded townspeople watched the soldiers march their captives through town. Merrill converted a building used for sugar manufacture into a prison and filled it to capacity with approximately three-dozen Klansmen the first day alone and 100 Klansmen after the first few weeks. He and his secretaries were flooded with confessions and testimony to transcribe from the arrestees as well as from hundreds more men who showed up at the door and turned themselves in to avoid soldiers coming for them. More details of the Jim Williams murder, as well as other horrible crimes, began to be filled in, with Dr. Bratton’s role fleshed out by one man after another. One local promised to lead Capt. Hale to one of their major targets. Instead, the man took him around in a circle, and a furious Hale added the trickster to the rapidly growing ranks of incarcerated men.

Hale’s quarry wasn’t the only Klan leader who slipped through Merrill’s fingers. Even as many of the Klan members began to turn against each other, Merrill had his own traitor in his midst. On the eve of the raids, Dick Clinton, his secretary, gave the names of some Klansmen whom Merrill was hunting to jeweler and Klan member Ed McCaffery. A cadre of “night runners” gathered at the county court house and scattered under the cover of darkness to warn the top Klan officers. Combined with a general plan to allow their foot soldiers to take the heat for them, many of the wealthy and high ranking leaders in the Klan—the same men who had held their heads high around Yorkville promising to help suppress the Klan—disappeared from their homes overnight, leaving behind families and businesses. Even with his improvised jail packed wall to wall, the vanishing of these men—including Bratton—enraged Merrill. He dismantled the Klan in a matter of hours, reporting to Washington that the organization was “completely crushed.” One newspaper put it more dramatically, writing that Merrill “held the whole infamous order in York County as if in the hollow of his hand, and he crushed it as easily as a man would an egg-shell.” But Merrill wanted to see the men most responsible for terrorizing this region publicly punished.

Dick Clinton’s motivation blurs with the distance of time. Clinton, whose treachery appears to have earned him a spot as one of the early inmates at the Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, military prison, may have secretly been a Klansman or simply have harbored sympathies, like so many whites in York County. If he was the same Dick Clinton who had served in the 13th Battery, Missouri Light Artillery, of the Confederate Army during the Civil War, he fought against Merrill’s cavalry in Arkansas eight years earlier when Merrill helped the Union Army take Little Rock. The former army private may have held a grudge born in blood that Merrill never even knew about.

6.

More than 100 members of the York County Ku Klux Klan fled either before the arrests or during Merrill’s mass dragnet. This included not only Dr. Bratton but also its other top county officer, “Grand Giant” James Avery. The Klan’s purposely opaque structure meant that only the higher officials could identify and implicate those running the organization. Administrative matters in Yorkville overwhelmed Merrill and his team as they sorted through prisoners and confessions, prepared cases with prosecutors, and searched for those still at large in the region. They even collected enough evidence for the attorney general to indict Sheriff Glenn. Merrill kept close watch on reports of fugitives’ whereabouts and urged Washington to devote resources to retrieving them.

Attempts to root out escaped suspects could quickly turn violent, especially when those suspects assumed that the Army would never harm its targets. When soldiers came for a fisherman named Minor Parris, he refused multiple commands to halt and was struck by a bullet. One of Merrill’s men nursed the Klansman, who was wanted for murder, for three hours before he died.

Government agents were a step behind Dr. Bratton from the start. First he fled to his sister’s home in another part of South Carolina. He went from there to Selma, Alabama, and then to Memphis, Tennessee, where he reunited with his brother John, also a fugitive from the Klan crackdown. Whenever Bratton heard that federal agents were closing in, he would move. When Memphis no longer felt safe, Bratton headed for Canada with other fugitives, possibly sailing from Florida to avoid detection. Gabriel Manigault, a member of an old South Carolina family who had relocated to London, Ontario, chose an out-of-the-way boarding house for Bratton. The same part of Canada, suddenly an apparent Klan refuge, had been a haven for escaped slaves prior to emancipation.

Bringing Bratton back to Yorkville, for which Merrill continued to clamor that winter and spring, became far more complicated once the doctor crossed the Canadian border. The task of the daunting manhunt fell to a kind of shadowy version of Merrill, a larger-than-life character named Joseph Hester who was part detective, part con artist. Hester followed a doctrine of personal gain and glory. In contrast to Merrill’s war hero profile, his past was marked with strange and violent turns. As a naval officer for the Confederacy, he shot and killed his commanding officer in his sleep on board the rebel ship CSS Sumter. The officer apparently discovered Hester stealing supplies. Hester was arrested for the murder but ended up being released with impunity because of jurisdictional issues. The Union Navy later captured Hester for trying to sail his own ship, Pocahontas, through a blockade in Charleston, South Carolina. Records indicate he made a deal to serve as an operative for the Union side.

Hester by some accounts ended up joining the Ku Klux Klan, but that piece of his twisty history may have misconstrued his undercover work to infiltrate the Klan. Hester provided the public with some of the earliest photographs of the Klan’s costumes. Whatever the source of his inside knowledge, Hester was now a deputy U.S. marshal and in his native North Carolina became a counterpart to Merrill in South Carolina as what the press called “Ku Klux hunters”—with Hester’s exploits including a sting operation and the dramatic rescue of a man as he was about to be hanged. After attempting an apparent lottery fraud, Hester earned the nickname “Lottery Hester” in some circles, while the Fayetteville Eagle called him an “assassin and incendiary.” Such labels belied his physical appearance, for in contrast to Merrill’s athletic build Hester was a rather small man with an almost cherubic face.

The Daily Phoenix of Columbia, South Carolina, summed up his reputation more evenhandedly when it tagged him a “somewhat notorious detective.” Merrill recalled in a letter how President Lincoln, in a private meeting during the war, once looked into his eyes and said, “Remember, young man, there are some things which should be done which it would not do for superiors to order done.” Merrill, the military officer with a lawyer’s sensibility, would never quite internalize that approach, but for Hester, swerving outside the bounds of the law became second nature.

The 42-year-old marshal knew he had to tread carefully to succeed in delivering Bratton back to Merrill. He would lack true authority while operating on foreign soil. He’d command the tactical operation but needed to find someone else to be his arms and legs. It’s unclear how he managed to recruit a deputy clerk of the local crown attorney, or prosecutor. Presumably looking for a big payday, Isaac Bell Cornwall brought skills Hester lacked, knowing the byways of Ontario and having the necessary contacts to launch their operation.

If they corroborated their intelligence that the man they hunted was in Ontario, then they had to hatch a plan of capture before he got wind of their presence. Hester had been tipped off that Bratton used the name Simpson in previous hideouts and the doctor made the mistake of maintaining that alias. Cornwall searched for letters to Simpson at the London post office in an attempt to confirm Bratton was in the area, opening at least two of them and resealing them without authorization. The letters, posted from South Carolina, pleaded with the doctor to “keep out of the public eye” and urged him not to reply. The letters likely helped lead Hester to Bratton’s boarding house. Hester studied Bratton’s routines for weeks, all the while carefully drawing up his plot to snatch him. As his own alias, Hester mischievously chose “Hunter.”

On June 4, 1872, around 4 o’clock in the afternoon, Hester sat in a horse-drawn cab and watched Dr. Bratton walk along Waterloo Street. Bratton’s plain suit of patchwork gray and his flopping black hat made him look less a doctor than a farmer, which was his stated occupation in this assumed identity. He may have looked the part of a greying 50-year-old agrarian, but from Merrill’s dossier Hester anticipated the coldblooded Klan killer would put up a fight. Cornwall sat in a second hired cab, waiting for Hester’s command. Hester gave the signal. Hester’s cab now sped toward the doctor. Cornwall’s cab also came at full speed from the other direction. The two vehicles stopped on either side of Bratton, pinning him in.

Cornwall jumped down to the street and seized Bratton. Bratton tried to strike him with his walking stick and to choke Cornwall, but the deputy clerk was stronger and brought him to the ground. He held Bratton’s body down and secured one handcuff before ordering the cabman to help. Bratton tried to call out, but the hunters planned for this. Cornwall held a rag over his face and soon the struggling stopped. The cloth had been doused in chloroform. Cornwall pushed a now subdued Bratton into his vehicle. Hester ordered his cab to drive off, and Cornwall and their quarry rode in the other direction in the second cab.

Cornwall’s cab, with the drugged doctor, took the back roads to the train station. Hester went to the station, too, and sent a boy to scout the Pacific Express, which ran late. Worried an attempt could be made to liberate Bratton, Cornwall ordered his driver to drive up and down the streets, as close to the tracks as possible. Once the train arrived, the boy scoped out the train cars and reported back which were the least crowded. Cornwall escorted the doctor to a small sleeping apartment. The ride underway, they switched to a different berth—an extra precaution in case they had been noticed. Bratton emerged from his chloroformed state and protested.

Marshal Hester still remained out of sight. As soon as the train crossed the railway bridge out of Canadian territory, the door to the sleeping compartment opened. Hester was standing there.

“You go with me now,” he said. Hester announced Bratton was under arrest.

A ferry ride brought them to Detroit, where they hired a cab and ordered the driver to go as quickly as possible to the Central Police Station to register officially their capture. Bratton, despondent, was searched, the sergeant finding “$108.85 in money, a watch, pocketbook, and a surgeon’s lancet,” but nothing on him with his name. He claimed he was a farmer from Alabama named James Simpson (the name of one of Bratton’s uncles).

The captors brought Bratton to a hotel in Detroit called the Russell House, where they took turns staying awake on guard before Hester apparently paid Cornwall in the middle of the night and the deputy clerk went on his way. Hester took Bratton to South Carolina in a combination of trains and coaches, stopping at inns and hotels. Bratton would be chloroformed when needed, replacing the usual shrewd expression of Bratton’s face with a vacuous blank stare.

At Aquia Creek, Virginia, Bratton managed to slip away in the crowd of a train station. Hester searched the station and the train but found nothing. His experience pursuing desperadoes and fugitives—and once being a fugitive himself—allowed Hester to think like his prey. Bratton would assume Hester would watch the train station and would seek another way out, this time in a strange locale without the support he had in Tennessee and Ontario. Hester staked out the harbor all night, and when morning came, he found his prisoner hiding beneath the wharf, waiting for the first ship that might take him.

On June 10, 1872, Hester arrived in Yorkville with Bratton. He marched his prisoner through town and handed him over into Merrill’s custody. For Merrill, sitting across from the gaunt, weary man who helped mastermind the activities of the York County Klan, separated by cell bars, was an enormous moment, though speaking with him would prove infuriating as ever. This was the same man who at times denied even knowing that the Ku Klux Klan existed. (Regarding Jim Williams, Dr. Bratton’s niece would later imply the murder was self-defense, remarking that Williams threatened to “kill every Bratton from the cradle to the grave.”) Still, a note of triumph slips through the unadorned language in Merrill’s coded telegraphic dispatch back to Washington.

Dr. James Rufus Bratton arrested and now in jail here. Lewis Merrill, Major 7th Cavalry

The Klan’s ultimate weapon—its secrecy and the so-called invisibility of its members—had been stripped, and the aristocratic physician who had led two lives could no longer hide one because of the evidence amassed by Merrill. The federal government knew that its entire Army could not have tracked down every member of the Ku Klux Klan in the country (though exact membership numbers remain disputed, there were significant Klan dens in every Southern state), but by using “exemplary punishment” in York County, they sought to destabilize and deal a “fatal blow” to Klan chapters across the South. That punishment consisted of bypassing corruptible and ineffective state forces with deployments of the federal Army, and exposing and arresting as many Klansmen as possible in York. Though the process of bringing the prisoners to trial was ultimately riddled with complications, the example of mass arrests without habeas corpus sent a clear message to the organization’s leaders throughout the South. In the aftermath of the operation, the Ku Klux Klan, for all intents and purposes, was put out of commission and the next serious iteration of it would not surface for almost 40 years. The racial fault lines in America, of course, were not erased in a single mission. Merrill’s evisceration of York County’s Klan was one of countless battles to come.

The triumph of Bratton’s capture was particularly short-lived. Bratton, Klan supporters, and their political allies in the press and in Congress, managed to whip up an international frenzy of outrage over his capture, which they framed as an illegal kidnapping. The Canadian courts tried and convicted Isaac Cornwall, who became the drama’s scapegoat. He was handed a three-year prison sentence.

Two days after Bratton’s return in shackles to Yorkville, Judge George Seabrook Bryan of the circuit court, a former slave owner with deep ties to the South Carolina gentry, granted bail for Bratton in the amount of $12,000. The money—an enormous sum in 1872—was raised right away through sureties, or individuals who assumed financial responsibility if he did not meet his obligations to the court. Bratton never returned to jail, leaving behind the 13 men who guaranteed his bond and heading back to Canada, where he knew the international din would provide sufficient cover to stave off any arrest parties from crossing the border.

Merrill, Hester, and the soldiers of K Troop stood by and watched Bratton walk freely into the streets on his way out of town. Hester had observed that part of the power wielded by the Klansmen was the intimidation that came from the pretense that “they are not human beings.” Bratton was escaping justice. But he had become human and vulnerable again. The Klan stranglehold had been released, their ostensibly invisible empire brought into the light and broken to pieces, and in a place where terrified men had once hidden in the woods, what stood out most watching that scene was not the worn-down doctor retreating, but the confidence on the faces of the citizens he couldn’t chase away.

* * *

Reverberations from the military operations in Yorkville followed the key participants for many years. Merrill was harassed by those who opposed his mission in South Carolina, enduring accusations that he fraudulently collected reward money for the Ku Klux Klan arrests. He eventually overcame the backlash to be awarded the prestigious rank of lieutenant colonel. Rewarded for his years chasing Klansmen during the 1870s, Joseph Hester received desirable diplomatic assignments from Ulysses S. Grant (who was re-elected handily as president in 1872) in Chile and Austria before settling in Washington, D.C., as a businessman. For the 7th Cavalry’s K Troop, the future was less bright: Many of the soldiers who had served at Yorkville were killed five years later, under the command of Gen. George Armstrong Custer at the Battle of Little Bighorn.

Dr. J. Rufus Bratton, when he was confident he would not be prosecuted for his crimes, eventually returned to Yorkville. Many welcomed him back as a hero. He died at 76 years old. Bratton’s story was one of the inspirations for the novel The Clansman, later adapted into The Birth of a Nation, D.W. Griffith’s epic film that was successfully used as propaganda to inspire a Ku Klux Klan resurgence.

A Note on Sources

Telling the story of Maj. Lewis Merrill and K Troop’s mission in York County, South Carolina, involves exploring a voluminous and disjointed historical record, perhaps one reason some chroniclers (in the words of one scholar) “tend to minimize or overlook this episode.” Source materials include the papers of Ulysses S. Grant and thousands of pages of government reports of testimony and related documents collected by the “Joint Select Committee to Inquire Into the Condition of Affairs in the Late Insurrectionary States.” The military letters and telegraphs between Merrill and other officials are spread out mostly between the Library of Congress and National Archives. Contemporary newspaper reports, notably from the Yorkville Enquirer, provide a real-time window into many of the events. Assorted historical memoirs with insights into the events include the diaries of Winfield Scott Harvey (in the Library of Congress); Ten Years With Custer: A 7th Cavalryman’s Memoirs by John Ryan, edited by Sandy Barnard; and Louis Post’s reminiscences published as “A ‘Carpetbagger’ in South Carolina.” All of these sources, of course, come with their own perspectives and biases that must be weighed when synthesized into narrative.

Military, legal, and Reconstruction scholarship that informed and guided me include the excellent writings of Stephen Budiansky, Robert Coakley, J. Michael Martinez, Andrew Myers, James Sefton, Everette Swinney, Allen Trelease, Wyn Craig Wade, Mark Weiner, Jerry West, Lou Faulkner Williams, and Richard Zuczek.