The Athens of Ohio

What a historian discovered when she trained her eye on the town she calls home.

Photo courtesy of Athens County Historical Society and Museum

Late this summer, I wrote in Slate about my sad lack of knowledge of local history, and resolved to learn more about the place where I live: Athens, Ohio. I put together a series of open-ended questions to guide my research, and asked readers to join me in a little bit of a scavenger hunt, looking to answer queries like “Were there ever any major disasters, tragedies, or famous crimes in your town?” and “What’s the history of labor in your town?” (I’ve collected some of the answers I received from readers in the map below.)

Since starting this project, I’ve visited a cemetery, a cave, an archaeological lab, and the town’s Historical Society. I finally read the town history that I bought, aspirationally, when I first moved here (Athens, Ohio: The Village Years, by former Ohio University history professor Robert L. Daniel). Like many of the area’s earliest white settlers, I’m a transplant from New England, and have often found myself a bit homesick for the part of the country where I grew up. I learned that there’s an unexpected benefit of doing local history, for a transplant like myself: It can make you feel more at home.

Photo courtesy of Rebecca Onion

Which native American tribes lived in your area? What happened to them?

I asked Paul Patton, a professor of archaeology and anthropology at Ohio University, about the area’s indigenous history. He told me that between 1000 B.C. and 200, The Plains, a town next to Athens, was home to the second-largest number of Native Americans of the Adena culture in the area. The earthworks in The Plains—burial mounds and ceremonial land art—were constructed between 300 B.C. and 200.

White people who settled in the area remarked upon the mounds’ existence as soon as they arrived, and a (possibly inaccurate) map of the mounds can be found in Ancient Monuments of the Mississippi Valley, published by the Smithsonian in 1848. Most of the mounds were excavated without much care as the area was settled. Daniel writes that 19th-century workers leveling a mound in the nearby town of Chauncey found “an ornamented dress covered with copper beads, which the excavators proceeded to cut into pieces and distribute to bystanders as souvenirs.”

Patton also told me about archaeological work that had taken place at Ash Cave, about 45 minutes west of Athens, in the Hocking Hills area. This place, he said, had been a stopping place for indigenous people for centuries, before white people came to the area. He told me enthusiastically about the discovery of goosefoot seeds at the site, which showed that native people cultivated the resilient plant for food there; he is now working on a project that’s trying to bring this native relative of quinoa back into agricultural circulation in Southeastern Ohio.

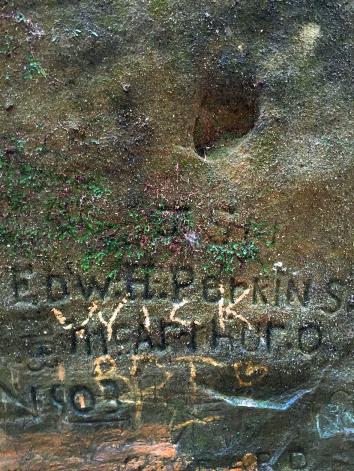

I visited Ash Cave, which is more like a giant overhanging ledge, so large that it has its own damp climate. I sat against its 700-foot-wide bulk, watching families run around underneath; graffiti from as early as 1903 was scored into the bottom ten feet of the rock, showing how people had put this singular place to their own uses, year after year.

Photo courtesy of Rebecca Onion

Athens proper wasn’t home to any Native people when white people settled the area in the late 18th century; there’s little evidence that any indigenous people inhabited the area permanently between the end of the Adena era and the beginning of white settlement, possibly because the landscape, which is scored with steep ridges, is less hospitable to agriculture than other nearby places. There were bloody conflicts between British settlers from Virginia and people of the Shawnee, Seneca-Cayuga, and Delaware tribes, at sites north and west of here, right before the Revolutionary War. But in 1800, when Rufus Putnam, a former brigadier general in the Continental Army who invested in real estate after the war, acted on behalf of the Ohio Company to clear out white squatters and establish a permanent settlement here, the Native presence in this particular place was gone.

Photo courtesy of Rebecca Onion

Was slavery ever legal in your town? When? If it was, how many enslaved people lived in the area, and what kind of work did they do? Why did the law change when it did?

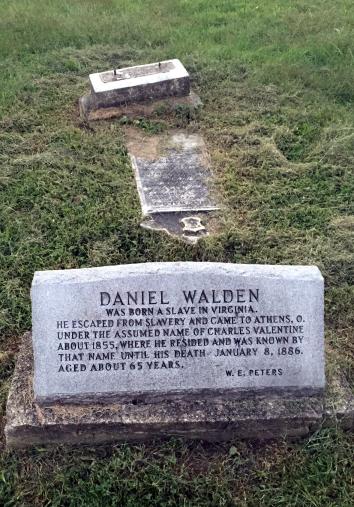

Here’s the grave of Daniel Walden, a runaway slave also known as Charles Valentine, in the city’s West State Street Cemetery. W.E. Peters, a local attorney who had an interest in history and genealogy, cataloged many of the local cemeteries in the 1930s, and the information he recorded appears on this memorial stone. Many of the graves in this cemetery are in poor repair (Walden/Valentine’s first grave, visible behind his new one, is representative of a majority of the stones here).

While slavery was never legal in Ohio, Athens was close enough to the South to see plenty of controversy over slavery. Advertisements for runaways appeared in the Athens newspapers, and there’s some evidence of Underground Railroad activity in the area (Robert Daniel cites the testimony of Athenians who remember spotting hidden fugitives and hearing of nighttime movements around town). In 1856, a year before the Dred Scott decision, writes Daniel, a white traveler named Brown brought a black enslaved child into the village and stayed overnight. “At this point, Charles Grimes, a colored citizen of the village challenged Brown’s ownership of the child,” Daniel writes, “alleging that by voluntarily bringing the child into a free state, he had forfeited legal possession.” The probate court issued a writ of habeas corpus and the owner decided not to contest it; the child was freed.

As was the case in many American communities, race relations were fraught in Athens during the Civil War. The story of two Athenians illustrates this well. Milton M. Holland, born into slavery in Texas and sent north by his owner (and possibly father) to attend the nearby Albany Manual Labor Academy, was 18 when he joined the Union Army in Athens in 1863. Holland, who recruited more than 100 black soldiers, was to lead the Athens County Company of the Fifth Regiment of the U.S. Colored Troops; eventually, he won a Congressional Medal of Honor for bravery in service. Meanwhile, Col. R.E. Constable, a man Daniel described as a “perennial officeholder of Athens,” spoke at a Fourth of July celebration in nearby Amesville in 1862, issuing a racist diatribe full of foul language. Daniel writes that Constable, a Copperhead, couldn’t stand the idea that the Union Army was fighting for emancipation: “Constable suggested that if the blacks were freed, South Carolina should be fenced in and once all the blacks were assembled there, one should ‘sink it to hell.’ ”

After the war, Rendville, a small company town built around a coal mine in Perry County, was founded with the express purpose of hiring black miners—a practice many white workers in the area found distasteful and would not allow. White miners from nearby communities twice attacked Rendville in the 1880s. In 1881, Christopher Davis, a black farmworker, was accused of rape and attempted murder of his white female employer. He was taken from the Athens Jail and lynched before his trial. An 1883 history of the Hocking Valley noted that the lynching was never investigated: “No one has ever been brought to justice for complicity in it. In fact, public sympathy was so strong that little effort was made to investigate the facts.”

What did most people in your town do for work 50/100/150 years ago?

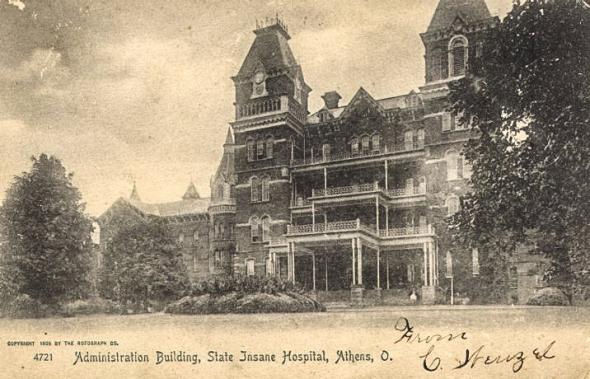

The Athens State Hospital, built in 1874, followed the design philosophy of physician Thomas Story Kirkbride, and was housed on gorgeous grounds. (The hospital moved to a different building in 1993, and the site is now owned by Ohio University; it’s used for offices, a physics lab, an art gallery, and a nursery school.) The hospital, which treated the mentally ill of Ohio, was Athens’ largest employer for almost 100 years.

Daniel writes that there were patient abuse scandals at the hospital, which suffered from overcrowding in the early 20th century; a patient died, and there were allegations that two others had been impregnated by attendants. Traveling neurologist Walter J. Freeman performed trans-orbital lobotomies on site in the midcentury years. These stories, the inherent nature of the place’s mission, and the Victorian buildings (some of which have been abandoned for various periods of time), make the asylum catnip for ghost hunters. (Here’s a typical website that features the asylum’s name in a truly terrifying font.)

When I visited the Athens Historical Society, curator Jessica Cyders recommended that I look at two photo albums compiled by nurses who were educated at the State Hospital’s training school in the early twentieth century. These books, full of sentimental keepsakes, must be disappointing to any visitor looking for sensationalist history of this place. To me, they brought home the point that the “creepy” historical reputation of asylums covers up another more mundane, but still fascinating, story. Hospitals—of course—were people’s workplaces.

Nurse Netta Mapes and her friends took pictures of each other on the grounds, on picnics, and with patients at carnivals and other festive events.

Photo courtesy of Athens County Historical Society and Museum

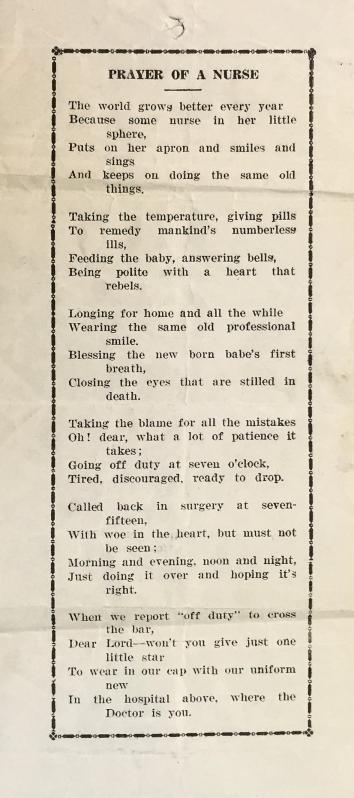

Mapes saved this broadside, “Prayer of a Nurse,” which gave a sense of the nurses’ feelings about their labor.

Photo courtesy of Athens County Historical Society and Museum

My favorite photo in Mapes’ album was this postcard, which Mapes had inscribed on the back with the story of its making. “We were not allowed to go uptown without permission after night time,” she wrote of herself and her fellow nurses.

This night six of us got the three girls that live next door to us and paraded through the streets, went to a show and had our pictures taken. Just as we were coming out of the show we ran into one of the doctors and made him promise not to tell on us and take us to a soda fountain and set us up.

The group, smiling in caps and gowns, looks full of moxie.

Photo courtesy of Athens County Historical Society and Museum

Does it make a difference to the way I live in Athens to know that Cornwell Jewelers, where I recently went to get a hair clip mended, began as a clock repair shop and daguerreotypist way back in 1832? Or that Charles Grosvenor, the namesake of one of my favorite streets in town, was an Athens attorney who was a Civil War general and later a U.S. congressman? Or that the West Side of town, now a neighborhood where many students and young people live, once housed a train depot and was infamous for its saloons and prostitution? (I now like my favorite Athens bar, The West End Ciderhouse—located on the corner across from the former depot—even more.)

The biggest takeaway from my project so far isn’t an answer to any one question. It’s a realization that doing local history is a practice with intangible benefits. The go-to mode of engagement for people interested in history is often reading—as my groaning bookshelves can attest. There’s so much text out there to absorb, and it can be tempting to stay indoors and absorb it. But in the months when I challenged myself to find out more about local history, I sat next to a remarkable slab of rock; saw the sunset from a new vantage point, in a cemetery I’d walked past many times but never ventured into; and started looking at roadside plants in a different way. I also met some friendly people, and caught wind of community projects I wouldn’t otherwise have heard about. I think I’m going to make local history a habit.