Photo by Miguel Medina/AFP/Getty Images

Even by the standards of Bangui, the capital of Central African Republic and one of the poorest cities in the world, Saïdou is poor. Unlike the districts around it, with their neatly packed-in houses behind walls and gates, Saïdou, which occupies an oblong dirt plot near the city center, resembles a slum in a less orderly African city like Kinshasa or Lagos. That is another way of saying it resembles a village. There are no walls or gates. The one-story cinderblock homes face one another at strange angles. You go between them on dirt paths or by stepping through the undergrowth and over rivulets of gray water. To access Saïdou, you make a quick turn off the Avenue des Martyrs, slipping between a pair of high-rises. The high-rises are falling apart, and their residents are poor, too; but when they look down on Saïdou, they thank God, and the martyrs, for their luck.

Lamove and Serge Kamouss were born in one of those cinderblock homes. They grew up there, then started their own families nearby in Saïdou. It was to that home, where their mother now lived alone, that the brothers returned on an afternoon earlier this year. They each came unbeknownst to the other, each under a cloud of anger and shame.

In 2013 the Central African Republic had been taken over by a Muslim-led insurgent group called Séléka. Its forces had ransacked Bangui and killed and abused its citizens. Séléka infuriated Lamove, the older of the two, but he was jobless—he had been his entire adult life—and the new regime had needed men. So when he had been offered a job as a Séléka soldier, he’d taken it. Serge hadn’t been as lucky. Séléka had ruined his business and jailed and beaten him. Lamove, fearing for his new job and his life, had refused to help his brother. When they went to Saïdou that day, they hadn’t seen each other in months.

Lamove arrived first. He found his mother washing clothing. He knew she disapproved of his joining Séléka, and he tried to avoid talking about it with her. But the subject inevitably came up. He reminded her of how desperate he was, that he had children he couldn’t afford to feed. Madame Kamouss said it didn’t matter. Séléka had ruined their country, she told him. Its thugs had raped and killed members of their family.

As they were talking, they heard Serge’s voice outside. Madame Kamouss, who hadn’t been expecting her younger son, became frightened. She hadn’t seen Serge in weeks and feared that, after getting out of jail, he had joined anti-balaka, a Christian-led citizen militia that had formed to oust Séléka. The fighting had dragged the Central African Republic into a sectarian civil war that continues today. Serge was stronger than Lamove, in his youth a renowned brawler around Saïdou. Madame Kamouss knew he was furious with Lamove for not coming to his aid, and didn’t know what Serge might do. She hid Lamove in the bedroom.

Serge had come with friends his mother had never met, whom he left outside. Inside, after embracing him, she asked where he had been. He admitted that he had, in fact, become a fighter with anti-balaka. As she had feared, he and Lamove were now on opposing sides of the war.

“She got upset,” Serge recalled to me later. “She said, ‘They are dangerous. The anti-balaka are the evil people. They are killing people.’ She was really angry.” He told her that anti-balaka was trying to defend their country against Séléka, against the Muslims and foreign invaders who had usurped control. Séléka wanted to enslave Central Africans, and he was trying to stop them. As a Christian, she should understand this. “Our aim is to take back our country,” he told her. Madame Kamouss had raised her sons to respect people of all faiths, and, before joining anti-balaka, Serge had had Muslim colleagues and friends. No longer. Now he wanted to see every Muslim dead or gone. “They are traitors,” he said.

Lamove listened as they talked. He listened to his mother weep. Then their conversation turned to him.

“Do you want to hurt your brother?” Madame Kamouss asked Serge.

He said he didn’t.

Hearing this, Lamove slowly came out of the bedroom. He and Serge looked at one another.

Until last year, the Central African Republic had no history of religious conflict. Unlike in nearby Nigeria or Mali, where jihadist insurgencies have brought to a boil already-simmering religious tensions, or in its neighbor Sudan, where Muslims and Christians have long been at odds, Central Africans of different faiths have lived together peaceably for centuries. Its population was devastated by the Arab slave trade, but, unlike other sub-Saharan Africans, Central Africans don’t seem to hold a grudge. When, after a visit to Libya in 1976, Central African Republic President Jean-Bédel Bokassa took up the Quran and renamed himself Salah Addin Ahmed, his mostly Christian countrymen (about 85 percent, to about 15 percent Muslim) didn’t protest. They knew that he was trying to squeeze his sometime patron Muammar Qaddafi for aid, and understood that Bokassa, who kept a harem of foreign wives whom he referred to not by name but nationality, was no monk. They were no more surprised, nor any more outraged, when, soon afterward, he returned to the Catholic Church.

For that matter, the Central African Republic has surprisingly little history of conflict of any kind, though the conditions for unrest are certainly there: Its citizens live to an average age of only 49, during which time they spend an average of less than four years in school and make about $700 a year when they’re lucky enough to find work. They contend with the fourth-worst infant mortality rate in the world. The country is surrounded by turmoil—in addition to Sudan, it is bordered by the Democratic Republic of the Congo, South Sudan, and Chad—and full of guns that trickle in from those places. Yet, until last year, the Central African Republic had never known full-scale civil war. It was best known, if it was known at all, for playing unwilling host to Joseph Kony and his Lord’s Resistance Army. Since gaining its independence from France, the country has endured five coups d’état, and enjoyed only one real election, in 1993, but none of its presidents has died in office. The vanquished are bid gracious if wearied adieus by the populace, and the usurpers, usually known quantities, wary if peaceful welcomes.

Photo by Pierre Guillaud/AFP/Getty Images

Indeed, it’s uncommon to hear a Central African seriously badmouth a former leader. Bokassa, one of the most untenable despots of the last century, anywhere—he had himself crowned “Emperor of Central Africa” at a coronation ceremony that cost a quarter of the state budget, and then instituted dismemberment as punishment for petty crime—is remembered with near-unanimous fondness. They’re more likely to voice commiseration. Ours is a put-upon and ungovernable country, the argument goes, and anyone who’s tried to run it deserves at least some credit. It’s an attitude that derives in part from the native gentleness and in part from a contempt for government: The historian Pierre Kalck relates that, before the colonial era, the area’s leading tribes “were all opposed to the very notion of state.” One of their deities was Ngakola, once a venerated chief—so venerated, in fact, he was put to death by his subjects, who respected him too much to live under his rule.

“There is a mentality for Central Africans. We need always to live in suffering,” a civil servant in Bangui told me. “If we are suffering, then, I think, we feel at ease.” In Sango, the national tongue, there is a phrase for this: kanga bé. It translates roughly as “close your heart.” Faced with index-anchoring poverty, chronic political collapse, and cartoonish corruption, Central Africans say kanga bé. “Don’t do anything, don’t react, don’t say anything. Just wait it out,” is how a Central African friend summarized the expression. “It’s the answer to every misfortune.”

That dolorous unity finally broke down with the appearance of Séléka, which inflicted more suffering on Central Africans than they were willing to bear. Séléka, which means “alliance” in Sango, was made up of several rebel groups that for years had been making manageable trouble in the north of the country, where Muslims predominate. In late 2012, without much warning, the groups banded together under the leadership of Michel Djotodia, a onetime treasury official in Bangui and habitué of petty intrigue, and began pushing south toward Bangui.

Photo by Alain Amontchi/Reuters

Djotodia enlisted Chadian and Sudanese mercenaries with the promise of wealth and jobs once he was in control of the Central African Republic. According to government employees and soldiers I spoke with, Djotodia, who is Muslim, persuaded ministers, members of parliament, and military commanders in Bangui to come over to his side, and without much effort: The president he sought to unseat, François Bozizé, had, after 10 years in charge, lost what thin popularity he’d started with. Bozizé had himself come to power in a coup, in 2003, also with the help of Chadian mercenaries.

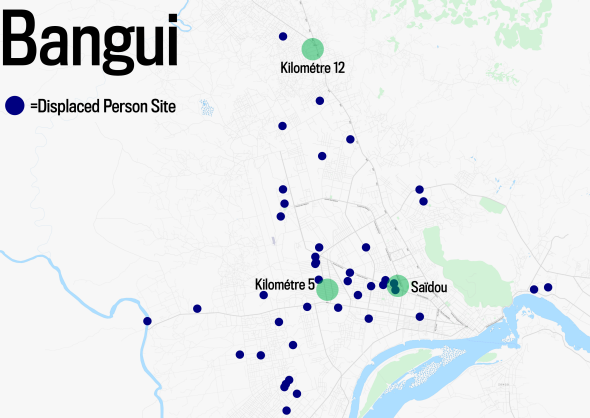

That support was short-lived. Djotodia’s fighters were soon out of his or anyone else’s control. The havoc they initiated has not stopped since. One hundred twenty thousand Central Africans have fled the country in the last two years, according to the U.N., and 400,000 remain displaced within it. The Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project estimates that 3,062 Central Africans have been killed in the conflict since 2013.

As a boy, Lamove Kamouss was obedient, a good student, an enthusiastic churchgoer. He was skinny and weak, but still he would carry goods from the market for neighbors. He was well-liked around Saïdou. His brother Serge was truculent and stubborn, constantly getting into fights, and though he won most of them—he’s muscular and quick—he dismayed his mother, a devout Catholic who preached nonviolence to the brothers.

They learned a lot from Madame Kamouss, who liked to call Bangui by its old nickname, a vestige of a more hopeful time: “Bangui la Coquette.” If ambitious, it was still apt. In the 1960s and ’70s, Bokassa attempted to turn the city into a major African capital, and the results are, as he was, preposterous but charming. Bangui is a mess of architectural styles—Futurist, Brutalist, debased Mediterranean, Third World Neoclassical kitsch—none of them too well or too badly executed. Its white façades have been soaked with red earth dust, giving the city a warm, clayey hue, and they are often stamped with the national motto, “Unité, Dignité, Travail”: Unity, Dignity, Work. It, too, has a truth to it: Though work is hard to come by in Bangui, the streets are alive with fantastic commerce. Vendors sell baguettes from wire baskets mounted on their heads, the loaves arranged in circular tiers, pointing toward the sky, making their bearers look like crazed priests. Two-man teams assail the ubiquitous mango trees, one partner climbing the trunk and crawling out on the branches, picking the fruit and throwing it down to the other, who then arranges the mangoes on a plastic grain sack or old bed sheet for sale. The overall effect is not, as in other African capitals, of development gone awry, but rather of development on hiatus; Bangui feels not like a place with a grim future but like a place where the future has ducked into the shade to rest.

But the city’s charm can take on a sinister tinge. Central African men greet one another by leaning in and bumping foreheads three times, in the center and on both sides, a lovely salutation that unmistakably calls to mind fighting rams. One of the most pleasing buildings in Bangui is the central prison, painted in the colors of the national flag, making it look like a giant Venetian rainbow pastry.

When they were young, Lamove and Serge’s father worked as a chef, making not even enough to feed the brothers and their three younger siblings. The family ate the leftovers he brought home. When there weren’t leftovers, their mother took food donations from the church. Sometimes they didn’t eat at all. After a Belgian-owned restaurant their father cooked in closed, he never found another job. Their mother sold cakes and fruits around Saïdou, but brought in barely any money. “After our father lost his job,” Lamove told me, through a Sango interpreter, “we lived by the hazards of circumstance.” Their siblings all died as children. “We didn’t have enough money to buy medicine for them.”

Photo by Siegfried Modola/Reuters

Serge and Lamove knew their situation wasn’t unique. They knew how badly off their country was. So they found it baffling that their father and mother idolized the French. The brothers heard constantly of how much better life had been under the colonial administration. They had learned enough in school to know this wasn’t true. Concerned with its more lucrative African possessions on the Atlantic, Paris had left the colony of Obangui-Chari to the dregs of the colonial office. “As a sample of our race,” a French administrator complained, “the choice of agents could hardly have been worse.” Those agents imprisoned the women and children of villages until the men met production quotas of timber, cotton, coffee, and other commodities. Between 1890 and 1940, it’s estimated, half the population of Obangui-Chari perished from forced labor or imported disease. André Gide was so horrified by what he found there, in 1947, he wrote “I cannot express the sorrow and impotence I feel.” When the French finally departed, 13 years later, they left a void: In a country of some 200,000 square miles (larger than France), there were almost no paved roads, little infrastructure, no professional class. The Central African Republic was “stillborn,” a historian observed. “It achieved independence in name only.”

In part, this was because France never really left. It kept control from Paris, tapping the Central African Republic’s leaders, managing its economy, and training its army, which it kept in check with a larger force of its own. Many Central Africans take it for granted that the major decisions about their country are still made in Paris. Whether this is true or not, Paris doesn’t go out of its way to dispel the impression. The French military has intervened in Central African crises five times since 1979.

Serge knew he couldn’t rely on the French any more than he could rely on his parents to help him make his way. He left school as a boy to work. First he caught fish in the Obangui River, which separates the Central African Republic from the Congo, hanging them on a stick and selling them. Then he peddled black-market gasoline. Once he’d built up some capital, he invested in bar soap, which he sold on foot around town. With the money he earned, he began buying oil, sugar, flour, onions, and other foodstuffs. In the early 2000s, he opened a small shop. It was in the market on Koudouku Avenue in to Kilomètre 5, a diverse district that contained many of the city’s Muslims, but also many Christians. His business grew; he hired couriers to travel to Cameroon to buy supplies. A pretty woman who made doughnuts came to his shop to buy corn flour and sugar. They married and had two children. “Life was good,” Serge, who is now 28, said of those years before Séléka arrived.

Lamove, now 40, wasn’t as resourceful. He did odd jobs around Saïdou and never found steady work. Serge supported him and the rest of the family. When Lamove had children, Serge paid to raise them. “It was difficult to take care of everybody at the same time,” Serge said, “but it was an obligation.”

Séléka poured into Bangui on the morning of March 24, 2013, in a tumult of trucks, cars, motorcycles, and technicals—flatbed pickups retrofitted with heavy machine guns. There was violence in Saïdou, but the district was too poor to invite looting. (As Serge put it, “We don’t have many VIPs.”) Few other districts were spared. Fearing the worst, some residents had stocked up on provisions and hid in their homes. Those caught outside weren’t as lucky. Though they encountered almost no resistance, Séléka forces came in shooting. By the end of the day, the streets were strewn with bodies. Houses, businesses, stores, government offices, and vehicles were looted and burned.

A Central African businesswoman whom I will call Anne (she did not want her real name used, for fear of reprisal) was at her home on a quiet street in an area not far from Saïdou, in Kilomètre 1, when the invasion began. A group of Séléka fighters forced their way into her house. They wore an assortment of uniforms, were heavily armed, and appeared “drunken, drugged,” she said, and “super-excited.” Because they spoke only Arabic and English, she concluded they were Chadian or Sudanese. “They put a gun to my head” and “they said, ‘We want money, we want everything you have, or we’ll shoot you.’ I told them to take whatever they wanted.” They did, and after about an hour of carrying out everything they could, left. But soon another Séléka band arrived. This one wanted her cars. Having anticipated this, she’d had her house staff dismantle the vehicles so they would be impossible to steal. Undeterred, the rebels settled in to fix them. Then a third group arrived and insisted the cars were theirs. An argument ensued, followed by a gun battle.

Photo by Sia Kambou/AFP/Getty Images

A judge, Romaric Kpangra, described events in his quarter, a few miles away. Several days after the coup began, a group of men came. They entered his home, where he had been hiding with his wife and young sons. He tried to reason with them, but they could not understand Sango or French. “I held my sons as they destroyed my home and carried away my possessions,” Kpangra said. They continued on to a neighboring house where two boys lived. Kpangra looked on as they shot the boys. “I was so terrified,” he said. “I don’t know why they were killed.”

Bangui took on the appearance of an open-air morgue and giant yard sale, with corpses and looted possessions everywhere. Anne said, “I literally saw my whole house” on the street in Kilomètre 5. (By some accounts, less damage was done in Muslim quarters than Christian ones.) The state, already anemic, collapsed. There was no water, no electricity, no services. President François Bozizé had fled the country. Michel Djotodia suspended the constitution and installed himself as president, but left the different factions that brought him to power to their own devices. Officials, soldiers, police, clergy, and community leaders were assassinated or went into hiding as vying Séléka “generals” carved out their territories, setting up roadblocks where passers-by were charged a toll when they weren’t robbed or attacked. Returning home one day, Anne came to a roadblock attended by a group of boys. From the other side, a couple approached. The boys gestured for her to wait, then turned around and fired their rifles at the couple. As the couple lay in the street, the boys slit their throats. Anne stood frozen. The boys returned and waved her on cheerily.

Like many Central Africans I spoke with, she and Kpangra initially sympathized with Séléka’s cause. “I thought Séléka was right about certain things,” said Kpangra, who agreed with the group’s criticisms of Bozizé’s corruption. Anne told me, “People were so fed up and tired of the [Bozizé] government that anyone could have taken over, and if they had just done the normal damage, people would have loved them, even if they were Muslim.”

Serge and Lamove’s aunt was killed by Séléka fighters. Two cousins were raped. At the same time, their father’s health was declining. Unable to afford medicine, their mother had been going to a wooded part of the city to collect plants and barks with which she made traditional remedies. They seemed to help. Then Séléka cut off access to the area. In April 2013, just weeks after the invasion, he died.

Lamove was devastated. But he was also more desperate than ever. Ashamed of himself and his circumstances, he was no longer the sweet young man his parents had been so proud of. He now had three children, and had taken to beating their mother, whom he couldn’t afford to marry. “He became more and more quick-tempered,” Madame Kamouss said. He’d stopped going to church. “When my father was alive, I was interested in religion,” Lamove told me. “But when he died, I lost the desire to worship.”

Séléka recruited not just local Muslims but jobless men and street kids. Many others, Muslim and Christian, volunteered, hoping to earn some money. When a friend of Lamove’s, a Muslim, called and said that he could get Lamove a position in Séléka, he didn’t deliberate long. “I was jobless. I suffered very much,” Lamove said. “I joined Séléka to get a job, to have the opportunity to do something.” Of Séléka’s political intentions he said, “I only knew that they came to rebuild the country, to give everybody jobs.” But he had no illusions about its methods. “Yes, of course I saw it,” he said when I asked if he’d witnessed any of the atrocities Séléka committed. “They stole from people, killed people, raped women.”

He was brought to a house Séléka had taken over and given a uniform and rifle. For three weeks he and about 20 other recruits were trained to shoot by a Chadian instructor. There was no talk of religion or politics. They were promised that, after the country was stable, their names would be entered into the army registry and they’d become real soldiers. But “we were treated badly. There wasn’t enough food.” Promised pay, he never received any.

Lamove didn’t tell his family he’d joined Séléka. When his mother noticed that he hadn’t been in Saïdou for some time, she got worried. An acquaintance told her he’d seen Lamove in a car with armed men. She called a family meeting. “The members of my family tried to calm me down,” she recalled. They told her to pray for Lamove. A cousin promised to find him. When he did, Lamove told him that Séléka had given him the first full-time job he’d ever had; he wasn’t going to let it go. “If I get out of Séléka,” Lamove said to him, “what are you going to do for me?”

Photo by Siegfried Modola/Reuters

When Lamove finally returned to Saïdou, his mother scolded him. “I reminded him of the circumstance in which his father died,” she said. “I told him that if he stayed in Séléka, my relation with him would be broken and he could no longer consider me his mother.”

While Séléka ransacked Bangui, Serge thought he was in a good position: his shop was in a Muslim-heavy area of Kilomètre 5. Some Muslim-owned businesses had been attacked, but not as many as Christian ones, he’d noticed. His Muslim clients and friends would protect him, he hoped.

They didn’t. A group of men came to his shop, and took his inventory and all the money he had. He was arrested and brought to a jail where, Serge says, he was beaten—punched, kicked, and whipped with metal wires. His arm was broken. When he got out, after a week, he called Lamove. For the first time, he had to ask his older brother for help. But Lamove told him he couldn’t do anything. “I really wanted to help him,” Lamove told me, but “I was out of the city, and Séléka kept moving us around.” Their mother took Serge to a hospital. Afterward, he asked Lamove for help again. Lamove said he could pay for medicine, but that was all. “If I had heard about it earlier, when Serge was in prison, I could have done something. But after he got out, what could I do?” Lamove said. “I was afraid of the chiefs of Séléka. If I tried to help Serge, it would be dangerous for me. It was so easy for them to kill people.”

Serge couldn’t understand. He’d never refused Lamove anything. He’d fed and clothed his brother’s children. “He is my older brother,” Serge told me. “He is supposed to do something for me.”

After his training was done, in the late spring of 2013, Séléka stationed Lamove in a camp in Bangui’s city center and attached him to a patrol unit. He was told to monitor other Séléka forces and keep them from committing abuses. This was an impossible task. No one listened to him, particularly the Chadians and Sudanese, and, Lamove said, even “in my unit, some people used to steal and pillage.” Later his unit was taken over by new commanders who “tried to make me rob and kill.” He claims he refused. He wasn’t punished, but he was taken off patrol. “We just stayed in the camp. We had nothing to do.”

Serge began hearing about an opposition movement. Commanded from Bossangoa, 200 miles north of Bangui, it had originated in local “auto-defense” groups, citizen militias that had been around for years. It was known as anti-balaka. In Sango the name literally means anti-machete. Figuratively it means indestructible. Anti-balaka fighters, draped in charms, were said to have supernatural powers; armed mostly with machetes, axes, clubs and knives, they were known to relish extreme brutality. As Séléka, fractured by internal dispute, pulled out of villages, anti-balaka swept in, killing Muslim civilians en masse. In Bossemptélé, a village near Bossangoa, anti-balaka forces slaughtered 100 Muslims in a day, according to Amnesty International. When survivors fled, anti-balaka hunted them down in the bush. “Muslims described seeing numerous bodies outside of town,” the organization reported, “rotting in the heat and being eaten by animals.”

Serge told his mother he was considering joining. She implored him not to. “I reproached and threatened him,” she said. “I could not imagine that he would join them.”

For two days after reaching Bossangoa, Serge waited near an anti-balaka training camp, sleeping on the street. When the chief of the camp returned, “He asked me many questions about my life, about my motivations for coming to the camp,” Serge said. “I told him what had happened to me in Bangui. I explained what I had endured.”

Photo by Ivan Lieman/AFP/Getty Images

He was put into training. With his strength and speed, he would have made an able soldier, but the anti-balaka commanders, poorly resourced and pressed for time, barely prepared him and other recruits for war. They weren’t taught to shoot or to handle explosives; their only instruction was with machetes. “We trained with the machete on trees,” Serge said. “The commanders said ‘This tree is a man in front of you. What will you do with this machete?’ ” Hearing this, he hacked at his tree with a strength and rage that impressed his new comrades and commanders alike. “They told us Central Africa was our country. We had to overthrow Séléka and defend this country from Muslims.”

In the first week of December, anti-balaka began staging raids on Bangui’s outskirts. Michel Djotodia had by that point formally disbanded Séléka, in an attempt to establish a legitimate government, but the group was already out of his control. In response to anti-balaka, ex-Séléka, as it was now calling itself, launched a campaign of indiscriminate killing in quarters of Bangui believed to be harboring rebels. Anti-balaka in turn stepped up attacks on Muslim civilians, enlisting Christian residents to help. By mid-December the Central African Republic was in a full-blown sectarian civil war. Some 935,000 people, or 20 percent of the population, fled their homes, according to the U.N. Footage of anti-balaka machete attacks and lynchings were uploaded to the Web. Muslims were beheaded, burned, mutilated. In one particularly gruesome clip that aired on the BBC, a man calling himself Mad Dog, who claimed that his pregnant wife had been killed by Séléka, chewed on what appeared to be meat from the leg of a Muslim man he had stabbed to death and then burned. Anti-balaka’s hideous signature was severed hands: The corpses of Muslims were often found with a hand cut off, in apparent mockery of the extreme-Shariah punishment for thieves. Sometimes hands were left with corpses, sometimes not.

During the worst of the violence, impromptu refugee camps formed around Bangui. The most organized camp, the main haven for Christians, sprung up next to the airport. It stretched over a dirt field alongside the sole runway. When I visited the camp, in April and May of this year, I spoke with refugees who were bivouacked in disused hangars and in and around old grounded planes. Fuselages were stacked with cookware, sleeping mats, and furniture, wings hung with laundry. They gathered on the runway in the afternoons, as the tarmac cooled; when planes landed, they scattered. Formally the camp, which is still there, and still home to thousands, is called M’Poko, but everyone knows it as the Ledger, after Bangui’s fanciest hotel. The main Muslim refuge is at the Grand Mosque, near Serge’s old shop on Koudouku Avenue in Kilomètre 5. While its grounds are smaller than M’Poko’s, the scene is similar: U.N. tents, women cooking, most people doing nothing. Its inhabitants also call it the Ledger.

Serge’s first battle was near a Muslim enclave in Kilomètre 12, a district on the northern edge of the city. He had to buy his own machete for the fight. Wrapped around his waist were amulets, small packets of plant clippings sown up in old vinyl furniture upholstery. The amulets were magical, the commanders explained, and had different powers: One could make Serge invisible to his enemies, another bulletproof, another disappear and reappear elsewhere. If he found himself pinned down, he was to squeeze one of them, and he would be protected. From a string on his neck hung a vial of special oil that would protect him from blades. Before the battle he was made to smoke from a “bad cigarette” and to swallow pills of some kind. He had no choice: Everyone took these “potions.” At first he worried what effect they would have, but then his mind sharpened and he was overcome with courage. He felt immune to the hunger pangs in his stomach, the aching in his feet, the punishing heat.

Serge’s commander and the more experienced fighters, with their Kalashnikovs, were in front, leading the charge along the road. Serge was in the rear, with the other new recruits. He longed to push forward. Ahead, running across the road, ducking behind trees and piles of cinderblock and mudbrick, he could see Séléka. But as soon as the battle had started, it seemed, it was over. With the first charge, Séléka dispersed.

I asked Serge whether he killed anyone in the fighting. He went quiet and averted his eyes. Finally he said, “No.” I couldn’t tell if he was embarrassed or lying.

Serge never met the anti-balaka higher-ups. In fact, he wasn’t sure who they were. Few were. Like everyone else, he’d heard rumors that François Bozizé was directing anti-balaka from his exile in Cameroon. Leading it in Bangui, nominally at least, was Patrice Ngaissona, a former member of parliament said to maintain close ties to Bozizé. Ngaissona is often in the company of a man who goes by Commander Maxim, a former policeman and the anti-balaka military chief. The group’s “spiritual leader” calls himself Douze Puissances, or Twelve Powers. He is said by his devotees to be able to shape-shift and project himself in multiple places at once. The man who brought me to meet the triumvirate, in April, said, “He did it to me just yesterday. I thought I was sitting with Douze Puissances, but it was only an image of him.”

I met all three at anti-balaka headquarters, which also happened to be the home of Ngaissona’s father, in Boy-Rabe, a vibrant, hilly section of Bangui. Ngaissona moved in after his own home was destroyed by Séléka. In a dirt yard were assembled several dozen men, none armed, all looking in need of some distraction, sitting among dust-covered buses and cars on cinderblocks.

I was shown to a gaudy sofa in a room that had recently witnessed a party: The walls were decorated in children’s birthday cards, and from the ceiling hung deflating balloons and upside-down bouquets of fake flowers. “This is my Ledger,” said Ngaissona. The surroundings, and his potbelly and slack shoulders, belied his reputation: Ngaissona has allegedly committed “crimes against humanity and incitation to genocide,” in the words of one warrant for his arrest.

Because “Séléka started raping and killing women,” he said, when I asked him why anti-balaka had formed. “They cut open the stomachs of pregnant women and took out the babies, they chopped off women’s breasts.” (One often hears these accusations in African wars. The physical evidence for them is harder to find.) When “they started burning Christian symbols, destroying churches,” it became clear to him that Séléka “wanted to make Central Africa into an Islamic state.” There were some grains of truth to this—Islamist sentiment was strong among the Chadian and Sudanese mercenaries, and it was no secret that many Central African Muslims had long hoped for a Muslim leader. But Djotodia, who like many Central Africans comes from a mixed-faith family, never attested to having that goal in mind. “What I want you to understand is that these people were rural villagers,” Ngaissona said. “They needed someone with open eyes to guide them, especially against Séléka.”

Maxim told me most of the police under his command were assassinated. “Can you imagine? People taking power and becoming killing machines?” he said. “They wanted to implement the Chadian system: Whoever does not practice Islam is an enemy of Islam.”

When I asked if anti-balaka killed Muslim civilians, Ngaissona shook his head and said, “I have Muslims in my family.” There were even Muslims in anti-balaka. “I personally have Muslim friends who are also my collaborators, and we have good relationships. Anti-balaka will never attack a Central African Muslim.” The distinction was one I heard again and again, and I eventually concluded it was a false one. Many Central African families, and not just Muslim ones, are immigrants. They’ve come from Cameroon, Chad, Senegal, Guinea, Nigeria and other countries. Many Central Africans have spent much of their lives abroad. The standards of foreignness often seem to be applied post facto: If Muslims had been killed, went the anti-balaka logic, they must have been foreign, because anti-balaka didn’t kill their countrymen.

While they spoke, Douze Puissances sat silent, staring thoughtfully at the floor. The only sounds that came from his chair during the conversation were two cellphone rings (to the tunes of “We Wish You a Merry Christmas” and “Hot Hot Hot”). His colleagues introduced me, but would not allow me to speak with him.

“What you need to know about Douze Puissances is that his wife and children were burned to death inside their home when Séléka attacked,” Maxim said.

Photo by Toby Woodbridge/Demotix/Corbis

Amid the carnage, there were examples of moral courage. I spoke with Bangui residents, Christians and Muslims, who risked their lives to protect their neighbors, friends, and family members from the other religion. The most famous example is the archbishop of Bangui, who took the city’s chief imam in after the imam’s home was destroyed. When I spoke to the imam, Oumar Layama, months later, he was still living at the diocese, going out rarely and then only in the company of armed guards, because he feared being attacked—as much by ex-Séléka as by anti-balaka.

Still, by January of this year, Muslims were fleeing the Central African Republic in the tens of thousands. Convoys of hundreds of vehicles packed with people could be seen rolling out of Bangui daily. Amnesty International accused anti-balaka of attempting an “ethnic cleansing” of Muslims. John Ging, director of operations for the U.N. Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, warned the conflict had “all the elements that we have seen elsewhere in places like Rwanda and Bosnia. The elements are there, the seeds are there, for a genocide.”

French troops arrived in December, as anti-balaka attacked Bangui, and were soon joined by several thousand African Union troops. They took control of the airport and set up checkpoints in embattled quarters. They put an end to the bigger street battles between ex-Séléka and anti-balaka, commemorating the achievement by installing roadside billboards showing a smiling white French soldier and a smiling black African soldier in front of the cityscape. For a time, citizens, too, were eager to express their appreciation. On Koudouku Avenue you could see a spray-painted graffiti note in neat white lettering: “Thank you for restoring peace and order to Kilomètre 5.”

But the killing didn’t stop. It became more personal, with tit-for-tat murders and mutilations. Defaced corpses turned up near mosques and churches every morning. Soon the international forces came in for blame. One night, after returning from Serge and Lamove’s home in Saïdou, I was awakened by a firefight. Automatic-weapons bursts and grenade explosions lasted into the dawn. In the early morning, I arrived in a Muslim quarter of Kilomètre 5, not far from the Grand Mosque. A local contact led me to a house where part of the fight had taken place. Fresh blood was pooled on a wooden bench in the courtyard and spattered on the wall above it. I was informed that two young men, the brothers of the owner of the house, had been sitting on the bench when a group of armed men approached and, without provocation, shot them. Who were the attackers? “The French and anti-balaka came together,” I was told. “They came to kill Muslims.” This was implausible, but the angry crowd gathering at the house had already accepted it as fact. Some in the crowd theorized that I was a French spy, a theory that, happily, did not catch on.

Photo by Andreea Campeanu/Reuters

Across an alleyway was the house where the worst fighting appeared to have occurred. Its exterior was pocked with hundreds of bullet holes, and inside, the rooms were ransacked, the floor piled with broken furniture. On the second story, below a window, was a perfectly circular hole in the masonry. There were two similar but smaller holes in two interior walls: a rocket-propelled grenade had gone straight through.

The destroyed house was on Avenue de France, a wide dirt track that cuts through Kilomètre 5. About 200 meters down the avenue and across a small bridge is a Christian quarter. Along the avenue, I passed Rwandan and Burundian troops grouped around a tank and an armored personnel carrier; none of them would discuss what had happened. Once in the Christian quarter, I spoke with residents gathered along the roadside. “We cannot go there because the Muslims have killed people,” a woman said, pointing to where I’d just come from. Her neighbor chimed in. “Everybody is afraid,” he said. “But before the crisis, we used to go there. We’d go there, and they’d come here. Before the crisis, we had many friends from the other side.”

I approached a group of young people who had gathered beneath a mango tree. “You are a spy!” a woman yelled at me. Once she had calmed down, she and her companions explained that during the last part of the firefight earlier that morning, two locals, a boy and a man in his 20s, brothers, had been shot. The boy sat in a plastic chair under the tree, shirtless, bloodstained bandages on his chest and arm. He recounted that he was at home when he heard gunfire. He came out and saw men in uniforms. “As soon as I heard the shooting, I was shot,” he said. “I was shot by the Muslims.” When I pointed out that ex-Séléka no longer wore uniforms, and that the only people around in uniform were the Rwandan and Burundian troops, the boy’s other brother, Modeste, told me that it was the same thing—the troops were allied with the Muslims.

“Every time Muslims come here, they kill people,” Modeste said. “We don’t trust anyone, even the soldiers from Rwanda. They were present when my brothers were shot.”

We were joined by a friend of Modeste’s whose white pants had turned a deep pink from fresh bloodstains. I asked the friend, whose name was Prince, what had happened. When Modeste’s older brother had been shot, he explained, he had picked him up and carried him down the avenue. “This is his brother’s blood,” Prince said. He had loaded him onto a handcart, which he and Modeste pushed to a hospital. Modeste’s brother died on the way.

Later that morning, they went to see the body. I went with them. “There are attacks every day. They even come and attack our homes,” Modeste told me as we walked. “Many people we know have been killed by Muslims.”

“The Burundians are part of the Muslims,” Prince said. “We can’t trust them.”

“Before the crisis, we had many Muslim neighbors,” Modeste said. “But during the crisis, they come from the mosque and they kill people. They’ve made a habit of it.”

We arrived at the morgue. An attendant in a dirty white coat led us into the cold-chamber room, which was hot and ripe with the sweet, sickly smell of decaying flesh. In what was apparently an attempt at gallows humor, the attendant knocked animatedly on the metal door of a body locker. Modeste frowned and told him he had the wrong one. They argued over which locker contained Modeste’s brother. Finally the attendant opened the door Modeste was pointing to, and pulled out the slab. The morgue had long since exceeded capacity, and on the slab lay two bodies. The arm and leg of a man no one knew were draped over Modeste’s brother, who was naked save for a bit of bed sheet. He was tall and thin, his jaw was taped shut, and on his chest was a child’s band-aid covering a small wound. He’d bled out, it seemed, from one tiny hole. Modeste looked at his brother with an expressionless face. As he and Prince left, the attendant asked them for money.

Photo by Marco Longari/AFP/Getty Images

“I can’t forget what happened. I have to take revenge,” Prince said, as they made their way back to Kilomètre 5. “The Muslims must be sent away from Central Africa.” He vowed to buy a gun. If he couldn’t get a gun, he would buy grenades, which were being sold in the anti-balaka-infested markets around Kilomètre 5 for 300 francs, or about 75 cents.

Modeste agreed. “Even if this country recovers, I’m going to kill Muslims from time to time,” he said. “I really don’t want to kill people, but the level of violence the Muslims have introduced is so high that I must kill them, too.”

Several days later I arrived at Koudouku Avenue late in the afternoon as an enraged crowd of Muslim men rushed from the Grand Mosque. At the crowd’s front, two men carried a body wrapped in a blanket. They brought it down the avenue to a checkpoint manned by Burundian peacekeepers. As the soldiers looked on, the men set the bundle down and pulled back the top flap of the blanket. The body, naked, belonged to a young man. There was a gash in the abdomen from which fat tissue sloughed. The head had been cut off. So had the right hand and the penis. The severed hand lay on his stomach, but the head and penis were missing.

“What are you going to do about this?” a man demanded of the Burundians.

“These people don’t want peace!” another yelled. “They’re animals!”

Looking for a target for its rage, part of the crowd caught sight of a taxi driving slowly by and lunged for the car. The driver screeched into a U-turn and sped off. As this was happening, the body-bearers lifted the bundle again and carried it toward an empty market street that connected to a Christian enclave. On the other end of the street, a crowd of onlookers had gathered. Faster than would have seemed possible, the two crowds were hurling threats at one another. As the Muslims made ready to move on the Christian crowd, a lone Burundian calmly stepped in front of them and raised his rifle. The men considered rushing the soldier, then thought better of it.

Afterward a Muslim resident explained that the corpse belonged to a local mentally handicapped teenager named Bashir. “His father was Muslim,” he told me, before I had a chance to ask, “but his mother was Christian.”

Lamove never learned who, if anyone, was really in charge of Séléka. He was not alone. It is an open question how much control Michel Djotodia or any other Central African ever wielded over the group. According to local journalists and historians I spoke with, if Séléka was under any one person’s thumb, it was not Djotodia’s but rather that of Chadian President Idriss Déby. Since the mid-1990s, Déby, a Muslim, has placed an increasingly heavy hand on his southern neighbor’s affairs. He harbored Bozizé in Chad after Bozizé botched a coup attempt in 2001, and then helped install him in the successful sequel two years later. Déby tired of his protégé for reasons no one seems able to agree on. (Déby has denied involvement with Séléka.)

Lamove didn’t know whom to blame for the fact that he was never paid, nor for the fact that his name was never entered into the army registry, as he’d been promised. He realized that the new regime had no more interest in helping men like him than any previous regime had. “I joined Séléka because I wanted to become a real soldier. I wanted a job,” he said. “I wanted change for the country. I didn’t want this.” In the fall of 2013, as Serge was training with anti-balaka, Lamove got rid of his uniform and gun, and returned to Saïdou. No one came looking for him. No one seemed to care.

Serge took part in only one more major fight after anti-balaka’s initial surge into Bangui. It was on Koudouku Avenue, near his old shop. Again he was draped in amulets, and again given the “bad cigarettes” and pills. “Those who had killed people were those who we attacked.” He said that the Muslims had attempted to do away with Christians in the Central African Republic, and deserved to have the same done to them.

Photo by Miguel Medina/AFP/Getty Images

He did not say “genocide,” but in that he is rare. The word is now used freely by Central African Christians to describe the situation under Séléka and by Muslims to describe their plight now. In Kilomètre 5, the messages of support for the foreign troops have been replaced by jagged red graffiti reading “NON ALA FRANCE” (NO TO FRANCE) and “GENOCIDE.” The situation has become a matter of concern to Islamist movements elsewhere. In February the Nigerian group Boko Haram released a statement in which it “vowed to avenge the spilled blood of Muslims massacred by the Christian anti-balaka militia in the Central African Republic.” An anti-balaka member who gathers intelligence for the group told me envoys from Boko Haram were already in the country. The al-Minbar Jihadi Media Network, an Islamist website, has called for the assassination of French President François Hollande in order to “support the vulnerable in the Central African Republic.”

In January of this year, Michel Djotodia fled into exile in Benin. The only visible figures of official authority in the Central African Republic when I left, in May, were the international troops and the occasional truckload of local gendarmes who never got out of their trucks. Ex-Séléka fighters still loyal to the cause had gone into hiding or retreated to the countryside. The rest, the men like Lamove, sank back into the population, as poor as ever. The first elements of a 12,000-person U.N. peacekeeping force were arriving. (It begins operations this month.)

The Muslim enclaves of Bangui grow smaller by the day or disappear altogether. On a Sunday morning in late April, I arrived in Kilomètre 12 as a convoy of more than 1,000 Muslims was preparing to head north to the Chadian border. A quarter-mile-long line of parked semitrailer trucks stretched downhill along a road that led out of the city. For months the Muslims had been living along this road in fear and squalor, taking refuge in ruined homes and the mosque. Peacekeepers had protected it, but anti-balaka had still infiltrated, executing people at night and lobbing grenades into yards. As the convoy prepared to leave, French troops set up a roadblock up the hill to keep back a growing crowd of restive Christians. African Union soldiers in APCs stood ready. The mood was tense.

The trailers were filled with the stuff of whole lives: dining room sets, bicycles, wheelbarrows, sofa cushions, suitcases, televisions, mattresses, plastic grain sacks filled with clothing, baskets, prayer rugs, plastic tubs, pots, pans, bedframes, skillets. From the sides of the trailers hung desk chairs, handcarts, giant bouquets of jerrycans, a motorcycle. There were also disassembled U.N. tents, metal sheeting, wooden posts: Wherever these people landed, they knew, it would be a long time before they found permanent homes again.

The men who hadn’t already fled or been killed helped the U.N. workers load the trucks and circulated with spears and handmade bows and arrows wrapped in electrical tape, promising protection and offering encouragement. Women and children gathered beside the trailers, cooking last-minute meals of fried fish and chicken and gathering up mangoes. A boy circulated with a cooler of sodas and beers for sale. A woman walked by me burdened as only a refugee woman can be: a bucket of mangoes balanced on her head; a bedroll under an arm; an infant, wrapped in cloth, slung on her back; a water can in one hand, an overloaded handbag in another; and, holding onto the hem of her dress, a small girl.

Though it was well-known that the convoy was leaving, taking with it the last Muslims of Kilomètre 12, some of whom had lived here since before the Central African Republic was a country, no one came to see it off. No imams, no politicians, no well-wishers. Muslim family members hiding out in other quarters wouldn’t dare expose themselves. The only people whose faces registered the sadness of what was happening were the young European U.N. workers. The refugees themselves wore expressions of eager duress. They just wanted to go.

I spoke with an old woman who was sitting with her very old parents. Her father was blind, her mother immobile. She was waiting for someone to tell them which truck to get on. She was born in Chad, she told me, and had come to the Central African Republic as a child, “more years ago than I can remember.” She’d been chased from her home by anti-balaka. “I am very sad to leave. But I have to because of the situation. No one is helping us,” she said. “I can never return to Central Africa.”

Photo by Issouf Sanogo/AFP/Getty Images

By midmorning the convoy was ready to move. The travelers sat atop their possessions in the trailers, waiting. As the sun arced toward noon, anticipation soured into worry. Rumors went around: France was not allowing the convoy to go; anti-balaka forces were on the road ahead, waiting to strike. Two men got into a fight over a table. An Italian U.N. official, trying to mediate, finally threw his hands in the air, kicked the table, and yelled, “C’est fini!”

Finally, just after noon, the engines came to life, and the convoy rolled down the hill slowly. In front and in back of it were the African Union APCs, which would accompany the convoy to the border. The vehicles were still in sight when the throng of Christians, having broken free of the roadblock up the hill, began streaming in. Within moments it was chaos. They kicked down doors, tore metal sheeting from fences and roofs. A crowd converged on the mosque, pulling anything they could from its façade. Dozens turned into hundreds, a wave of bodies. They whooped and hollered and danced. Boys beat empty plastic water bottles against their knees. People took whatever had been left behind, whatever they could. A man tipped a wooden kiosk onto its side on a handcart and pushed it up the hill.

The crowd far outnumbered the African troops who’d been left to maintain order and protect the mosque, and the scene turned ugly. Men emerged carrying axes and spears. Walking behind a tank as it rolled out of Kilomètre 12, I watched a man in the throes of a macabre jig, hopping from leg to leg, laughing, twirling a dead cat.

Three days later, as the convoy approached the town of Kabo, near the border with Chad, it was set upon, presumably by anti-balaka. A U.N. jeep was attacked with grenades, and the APCs and semitrailers were fired on. A refugee woman was shot in the head and killed.

Photo by Siegfried Modola/Reuters

Under pressure from U.N. sanctions and an International Criminal Court investigation, in July Séléka and anti-balaka signed a tentative peace deal. It was also signed, though not arranged, by the former mayor of Bangui, Catherine Samba-Panza, who was elected interim president by a transitional national council. Though no one, including her, seems to be in control in Bangui, many Central Africans still take it as given that all major decisions, or lack thereof, are being made in Paris. At a rally in Bangui, Samba-Panza praised the national army. (She didn’t mention that it had done almost nothing to stop Séléka.) After she left the stage, a group of soldiers surrounded a man they accused of being ex-Séléka. They beat him with bricks, stripped him, and stabbed him to death. Burundian peacekeepers tried to intervene, but when the crowd turned on them, they stepped away. The Central African soldiers dragged the man’s corpse through the street, heaped tires on it and set it alight. People snapped pictures. “We think it was OK that the soldiers killed him,” an employee of the repair shop that the tires came from told a reporter. “In Africa, you take my eye, and I will take yours. You take my arm, and I will take yours.”

It was not long after that that Serge and Lamove met at their mother’s home in Saïdou. After Lamove emerged from the bedroom, the brothers came face to face for the first time in months. After looking at one another warily for what seemed to their mother like minutes, Lamove asked Serge how he was. Serge said nothing. “I remembered what he had done while he was in Séléka,” Serge told me. Their mother upbraided him. “Your old brother is talking to you,” she said. “Why can’t you answer him?” Finally Serge spoke. He told Lamove about going to Bossangoa, about his training, about the fighting. Serge said he didn’t want to keep the men outside waiting, and left.

Photo by Joe Penney/Reuters

Some weeks later the brothers met again at the house. This time the conversation was longer. Lamove told Serge that he’d quit Séléka, and said it was a mistake to have ever joined. He’d been desperate, he explained. For much of his life, he’d had to rely on Serge. He was sick of not being able to feed his children, sick of feeling inadequate. He didn’t want to turn out like their father. He admitted the mother of his children had left him for another man in Saïdou. Serge confessed that his wife, too, had left him. This time it was easier to speak. “Our misunderstanding was over,” Lamove said. “We even ate together.”

They did disagree about anti-balaka, however, which today is in control, at least spectrally, in most of the west and much of the south of the country, patrolling villages and roadways, as well as in Bangui; its fighters can be found in the quarters where the international troops don’t go, which is most of them. When anti-balaka formed, Lamove said, he held out hope that it would be better than Séléka. “I knew that they came for the revenge, because of what Séléka did,” he said, but “we thought that they would help people. But they did bad things. They robbed people and took things by force.” Serge conceded there were bad elements, but argued they were thugs who’d glommed on to a liberation movement.

Their mother was relieved to see them together. Still, her husband’s death, and her country’s travails, weighed on her. “My mother does nothing at present,” Serge told me. “She is often sad.”

Lamove said, “I want my country to know change. The country must become good.” He lamented that “other countries move forward, but not our country.” I asked if he believed this war was a religious one. It is a tricky question. Many Central Africans I put it to, Christians and Muslims, answered by saying that they have always gotten along and there’s no reason they shouldn’t continue to. Indeed, most anti-balaka and Séléka I spoke with said this. I often got the sense they said this because they thought it was what a foreigner would want to hear, or what they wanted to believe, not what they knew to be true. Lamove probably knew he could have answered this way. But he didn’t. “Muslims wanted to get into power,” he told me. “In their minds, when they got into the power, they wanted to take us as slaves, they wanted to destroy us.”

Serge nodded. “They must leave,” he said.

On this point, the brothers agree.