On Friday, Aug. 16, Margaret Mary Vojtko, an adjunct French professor who’d recently lost her job at Duquesne University at the age of 83, suffered a cardiac arrest on a street corner in Homestead, Pa.* Vojtko collapsed yards from the house where she had lived almost her entire life. She was rushed to the hospital, but she never regained consciousness. Vojtko died on Sunday, Sept. 1.

Photo courtesy Joseph Ball/Off the Bluff

Two and a half weeks later, Vojtko’s lawyer, Daniel Kovalik, published an op-ed about Vojtko called “Death of an Adjunct” in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Kovalik wrote that “unlike a well-paid tenured professor, Margaret Mary worked on a contract basis from semester to semester, with no job security, no benefits, and with a salary of $3,000 to $3,500 per three-credit course.” (In fact, for many years, she’d earned less—only $2,556 per course.) She’d been receiving cancer treatment, he said, and she’d become essentially homeless over the winter because she couldn’t afford to maintain and heat her house. Then, in the spring, she’d been told that her contract wouldn’t be extended after the current semester. A social worker from a local government agency had been tipped off that she might need help taking care of herself, which horrified Vojtko—“For a proud professional like Margaret Mary, this was the last straw,” according to the op-ed.

Kovalik, the senior associate general counsel at the United Steelworkers, faulted Duquesne for failing to do more to help Vojtko and for refusing to recognize a union, formed by its adjunct professors with his help, which would have fought for better pay, benefits, and job security. Kovalik’s not-so-subtle implication was that if Duquesne had negotiated, Vojtko might not have died the way she did.

Sites like the Chronicle of Higher Education, the Huffington Post, and Gawker quickly picked up the story, and Kovalik’s op-ed racked up more than 438,000 page views and 69,000 Facebook likes. Vojtko’s death especially struck a nerve with academics and graduate students, who saw shades of their own futures in her apparent abandonment. They took to Twitter with the hashtag #IamMargaretMary. “So many of us are walking into academic careers destined to be haunted w/ the same sort of contingency,” read one typical tweet. “#Adjunct labour in #HigherEd makes a more tangible product than #WallSt, & rakes in money for schools, but gets peanuts,” read another. One professor titled his blog post about Vojtko’s death: “This Job Can Kill You. Literally.”

It’s obvious why Kovalik’s op-ed inspired outrage: Elderly, recently let go from her job, and suffering from cancer, Vojtko was the picture of vulnerability. Duquesne, meanwhile, looked like the epitome of a coldhearted, corporate university—even though it is a Catholic school, founded by Spiritan priests. Tuition is $31,385 a year; meanwhile, Kovalik said Vojtko earned less than $25,000 from teaching eight classes a year. And though Vojtko had worked at the university for 25 years, when she was let go, she wasn’t entitled to severance pay, let alone a pension. Her situation seemed to embody everything that is wrong with the economics of higher education.

But was that true? Who was Margaret Mary—the person, not the symbol of victimhood? I went to Pittsburgh to find out more about the life of a woman who’d become famous only for her death. I talked to dozens of her family, friends, acquaintances, neighbors, and colleagues. I visited the campus where she’d taught for 25 years, the restaurant where she’d spent nights after her furnace broke, and the house she’d grown up and grown old in. The story I uncovered was more complicated than the story that went viral. The reasons Vojtko’s life ended in misery had much less to do with her status as an adjunct professor than tweeters using the #IamMargaretMary hashtag might believe.

At the same time, there is no doubt that Duquesne could have treated Vojtko better, or that recognition of the adjuncts’ union would make life better for the majority of teachers like her, who lack the status, job security, and financial benefits of tenured and tenure-track faculty. Adjuncts are the second-class citizens of academe: They are contract workers hired and paid on a per-course basis, with no possibility of tenure. They now make up about two-thirds of the academic workforce nationwide, and their numbers have been increasing steadily since the 1970s, as part of a larger trend in which universities, both private and public, are run more like businesses. While it’s hard to say exactly what Duquesne should have done for Vojtko in the months before she died, her case highlights the devil’s bargain universities have made by exploiting adjuncts—who, at Duquesne and elsewhere, are finally fighting back.

For the last two decades of her life, Vojtko ate virtually all of her meals in the cafeteria at UPMC Mercy, the Catholic hospital next to Duquesne where she was taken after she collapsed. One evening back in 1997, she offered some chocolate candy to a Capuchin friar named David Cira, who works in the hospital’s behavioral health unit, and they became fast friends.

I met Cira at Mercy one afternoon in September when he heard me talking to a receptionist, popped his head out of a doorway, and asked, “Is this about Margaret Vojtko?” Cira wears a hospital ID badge pinned to his brown robe and has a habit of bringing his hands to his cheeks, Home Alone-style, to convey shock. He led me into a counseling room and launched into his account of Vojtko’s life. It started off with the hallmarks of a second-generation immigrant success story.

Margaret Mary Paula Vojtko—who went by “Margaret” or “Marge”—was born in Homestead on Jan. 15, 1930, the youngest of six children. At the time, the town (located just outside Pittsburgh city limits) was home to one of the most productive and technologically advanced steel mills in the world, the Homestead Steel Works. Her parents were Catholic Slovaks. Her father worked in the steel mill’s boiler shop; two of her four older brothers also became laborers in the mill. The association that would become United Steelworkers organized the mill workers in 1937, and Margaret’s father joined the union.

The union fought for safer working conditions and better pay, but it still wasn’t easy to grow up in a big family on factory wages during the Great Depression. When Margaret was 7, her mother died suddenly. It fell to her sister Anne, who was 13 years older, to raise her. “Margaret always said that her sister was her mother,” Cira said. In her adulthood, Margaret once called home from Washington, D.C., to ask her sister for permission to buy a pair of shoes.

Margaret went to a Catholic high school run by the Vincentian Sisters of Charity, a local order of nuns founded to serve Slovak immigrants. Margaret was intensely pious, and when she graduated, she said she wanted to become a nun herself. Her father insisted that she work for a year first. So at 18, Vojtko became a secretary at the University of Pittsburgh, working closely with Max A. Lauffer, a pioneer in virus research. “She thought it was so exciting, that year at Pitt, that she never gave the convent a second thought,” Cira said. Her second cousin, Gerald Chinchar, says Margaret also figured out the convent wasn’t for her because she “had too much of an independent streak.”

By the late 1940s, United Steelworkers had succeeded in making laboring at the mill a solidly middle-class job, and Homestead was booming. In her 20s, Vojtko was known for dressing impeccably, always coordinating her shoes, purses, and hats. She had her first romances, falling for two men she’d stay in touch with for the rest of their lives, and turning down two other men who proposed to her. Vojtko never married, though according to Cira, she never stopped hoping she would meet the right person. In the meantime, she devoted herself to Homestead. “She was sort of the queen of the town in a certain way,” says William Serrin, a labor journalist who got to know Vojtko when he was writing his book Homestead in the early ’90s. “Everyone knew her. ‘Hi, Margaret!’ ‘Morning, Margaret!’ I always thought it was like out of Our Town.”

Photo by L.V. Anderson for Slate. Family portrait courtesy John and Carol Vojtko.

Vojtko wanted to pursue an advanced degree during this period, but it was only after her father’s death in 1957 that she freed herself from family obligations and went to college. She majored in French and Italian languages and literatures at Pitt, graduating cum laude in 1967 at the age of 37, and she earned her M.A. from Pitt in 1970. Vojtko went on to teach French and medieval literature classes at Carnegie-Mellon, Pitt, and Indiana University-Purdue University in Fort Wayne. She also earned money as a freelance editor and translator. Medieval studies were her passion: She once told Chinchar that she would have liked to live in the Middle Ages.

Vojtko’s friends frequently called her “brilliant.” She spoke five languages in addition to English, played the violin, earned a nursing degree, and studied theology in her spare time. (A very traditional Catholic, she strongly opposed Vatican II.) She got her job at Duquesne in 1988 based on her work as a translator, and started teaching a graduate-level class called “French for Research,” along with introductory language classes for undergrads. She took her pedagogic duties very seriously. “Teaching is not a profession or a career,” she told a campus magazine a few years ago. “It is a devotion—a dedication. Too many people look upon it as a job, a source of income.” She began the first class of each semester by explaining that she didn’t use Duquesne’s online portal for courses—she struggled with modern technology—and that she didn’t give students grades; they earned them. And though some students disliked Vojtko’s old-school approach to lecturing and grading, many were as devoted to her as she was to them, keeping in touch with her after class ended and offering her computer lessons.

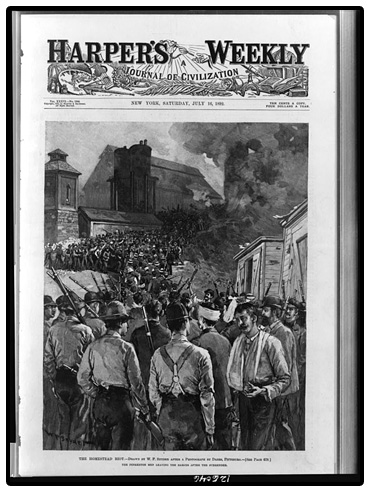

Courtesy drawn by W.P. Snyder after a photograph by Dabbs, Pittsburg/Harper's Weekly/Library of Congress

Vojtko had started work on a Ph.D. for Catholic University of America in the mid-1970s. For her dissertation subject, she chose not a French or medievalist topic that would have built on her previous research, but the role of Pittsburgh-area Catholic missionaries in the French and Indian War. Her research ended up focusing on an even narrower topic: the history of Homestead. Vojtko’s interest in the town became an obsession—and eventually endangered her health, relationships, and career.

Homestead is the site of one of the most spectacular strikes in American history. In 1892, Andrew Carnegie, the owner of the Homestead Works, decided to quash the mill’s skilled tradesmen’s union because he was frustrated with the restrictions it imposed on his ability to hire and fire workers. The town revolted. The Battle of Homestead, as it came to be known, was a deadly clash between striking steelworkers and the Pinkerton detectives who were hired to clear the way for strikebreakers. Vojtko, coming as she did from a family of steelworkers, admired the courage of the striking laborers (even though they lost the fight with Carnegie).

The Homestead Steel Works closed its doors in 1986. At the same time, Vojtko served as president of her town’s historical society, fighting to preserve the building used as the strikers’ headquarters in the Battle of Homestead. None of her preservation efforts related to her work at Duquesne. In fact, the other members of the Homestead Historical Society didn’t know she was a professor. They recognized her passion—and worried about where it led. Vojtko was proprietary about her research, and about objects. Once she had possession of an artifact—a billy club used in the Battle of Homestead, or scrap metal from the mill—she refused to part with it. “She would say she had them in her home, and we’d say, ‘Margaret, they really shouldn’t be in your home. I mean, there’s an insurance issue, and they need to be catalogued in, and they need to be public property,’ ” said Jan Carr, one of the founding members of the Homestead Historical Society. “She wouldn’t surrender them.”

At one meeting, Vojtko held up the billy club and refused to let anyone touch it. When other local historians tried to talk about moving her collection to a local museum, she always rebuffed them. The Homestead Historical Society stopped meeting in the early ’90s, in part because of other members’ frustration with Vojtko. Around the same time, she stopped letting anyone enter her house.

Houses, actually. Vojtko lived with her sister and brother, Anne and Eddie, in their two-story, yellow-brick childhood home, on Sylvan Avenue, until Anne died in 1980. At that point, Eddie (who, like Anne and Margaret, never married or had children) bought the house next door so he and Margaret could use it for storage. When Eddie died in 1993, Margaret inherited both houses and continued filling them with her belongings, piling boxes against the walls and windows. Along with her artifacts and historical documents, she kept newspapers, magazines, photographs, books, and much more.

A window at the back of the house Vojtko lived in, September 2013.

Photo by L.V. Anderson for Slate

People who hoard are often, like Vojtko, intelligent, creative, and endlessly curious, according to psychiatrist Randy O. Frost, a leading researcher on hoarding. They don’t easily distinguish between valuables and trash because they see beauty and potential in mundane objects, and because they worry that they might make a mistake by throwing away something they’ll need later. They use objects to help them remember the past.

In late September, I visited Vojtko’s block in Homestead, which is at the top of a steep hill. Even then, a month after her death, the front porch of her childhood home was a jumble of chairs, wooden boards, newspapers, boxes, plastic tubs, and planters filled with dirt. The windows of her second house were boarded up. Vojtko had this done in early 2012 after vandals broke some of her windows. (Since the mill closed, Homestead has had a high crime rate.) Ken Weir, the man who put up the boards, told me he saw “everything pushed up against the windows, like you were barricading yourself in.”

Throughout the 25 years she taught at Duquesne, Vojtko’s relationship with the university was uneasy. Though she worked on her dissertation for nearly 40 years, she never finished it, which meant she never became eligible for a tenure track position. As a traditional Catholic, Vojtko felt that the university wasn’t as religious as it should be. Staunchly pro-life, she was indignant when Duquesne held bioethics panels that suggested that contraception and abortion might be morally defensible. She also thought that Duquesne’s mission statement —which includes “Duquesne serves God by serving students”—was sacrilegious. Sébastien Renault, a close friend of Vojtko’s, remembers her saying, “It’s bad theology, because it doesn’t work this way. You don’t instrumentalize God. You serve God first. And the more you know him and love him and serve him, then you will serve the students.”

Renault says that although Vojtko was a devoted teacher, she became increasingly frustrated by her students, whom she came to see as self-absorbed and disrespectful. Duquesne students aren’t required to take classes on Catholic theology, and Vojtko thought religion should play a bigger role in their education. She didn’t hesitate to share her opposition to abortion, premarital sex, provocative clothing, and gay marriage with her students. She suspected some of her colleagues resented her moral principles and her “cleanness of life,” according to Renault.

Vojtko clashed most often with the chair of her department, Edith Krause. Vojtko felt that Krause treated her unfairly when it came to course assignments. Because she didn’t have a Ph.D., she was considered ineligible to fill in for a tenured professor who went on sabbatical. Privacy was another issue. In 2010, Duquesne’s Department of Modern Languages and Literature moved to a smaller building. Vojtko went from having her own office to sharing with five other adjuncts. The clutter at her workstation became a frequent subject of contention between her and Krause, Vojtko told friends. (I tried to talk to Krause for this story. “I have a cordial and professional relationship with all our adjunct faculty members. However, I am not able to discuss personnel matters,” she wrote back in an email.)

Last spring, Krause told Vojtko she was “no longer effective in the classroom” and that her contract would not be renewed. The university has not commented on the circumstances surrounding Vojtko’s dismissal. Vojtko told her version of the story in a complaint she filed with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. In that complaint, Vojtko said Krause cited her refusal to use technology and also complaints from students that she didn’t cover all the required course material. Vojtko denied both accusations. She stressed that she had taught French for Research for 25 years, adding, “No other Adjunct in the French section or in any other language section of the Department of Modern Languages has this record for length of service.” Yet, she wrote, “Dr. Krause had told me that the quality of my teaching was inadequate because I do not hold the Ph. D. degree.”

Kovalik gave me a copy of the complaint, which he helped Vojtko write, both because he felt sorry for her and because she belonged to Duquesne’s adjunct union. The group started to organize in 2011, when adjuncts in the English department asked for help from the United Steelworkers (which, these days, also represents health care workers, taxi drivers, and security guards). They wanted more money, and they knew Duquesne had it. The university’s most recent financial data show an endowment of more than $203 million and an annual surplus of $13 million. (Bridget Fare-Obersteiner, the university’s assistant vice president of public affairs, told me that the surplus goes to “principal payments on debt, capital improvements and renovations, capital equipment purchases and acquisitions, among others.”)

Organizers campaigned in the liberal arts college, asking adjuncts to sign cards stating that they wanted the United Steelworkers to represent them to negotiate better wages and health insurance. Vojtko enthusiastically signed. In the late ’90s, she’d begun battling cancer on and off, and though she had Medicare, her out-of-pocket costs for treatment were high. “She wanted more compensation for her work, and she didn’t think it was fair, the way they did the pay scale,” says Chinchar, her cousin.

Vojtko’s support for the union didn’t stem only from her concern about her own finances and her need for better health insurance. She was also delighted to be affiliated with the United Steelworkers, the organization that had won advances for the laborers at her beloved Homestead Works. She’d continued receiving United Steelworkers publications in the mail long after her father’s death. “She always said, ‘You have to understand that I come from a very strong union family,’ ” an acquaintance from Mercy Hospital told me.

The majority of Duquesne’s liberal arts adjuncts joined Vojtko in voting for union representation. Despite this support, Duquesne declined to recognize the union. At first, the university proposed a different method of gauging adjuncts’ support: a secret-ballot election to be administered by the National Labor Relations Board. Duquesne signed an agreement promising to abide by the results. To the adjuncts, that was good news: It was clear the results of the NLRB election would be the same as the results of the card campaign.

But about a month later—before the NLRB election took place—Duquesne reversed course. The administration hired a new lawyer and sought to withdraw from the recognition agreement. Duquesne’s new argument was that as a Catholic institution, it was beyond the NLRB’s reach.

The university’s newfound rationale incensed Vojtko. Two popes have written encyclicals in support of labor organization. Most recently, Benedict XVI wrote in 2009 that unions “have always been encouraged and supported by the church.” Robin Sowards, one of the adjunct union’s organizers, got to know Vojtko by chatting about Baudelaire as well as labor issues at union meetings. “She was toweringly angry that they refused to recognize us, and angrier still that they refused to recognize us by referring to religion,” Sowards said. The adjunct union went ahead with its election, and 85 percent of the adjuncts voted in favor of unionization. Duquesne appealed the election to the NLRB. The two sides have been locked in a stalemate, awaiting a ruling, ever since. (Anyone interested in the details and shortcomings of Duquesne’s claim that it’s outside the NLRB’s jurisdiction should read Moshe Z. Marvit’s terrific account of the legal battle in the labor magazine Unionosity.)

Meanwhile, in the absence of a union, Duquesne had gradually cut Vojtko’s teaching load from three courses per semester to two and then to one, which meant her earnings dropped precipitously. “I am my sole support and have no other resource except Social Security which covers my expenses for food, utilities, and incidentals,” she wrote in her EEOC complaint. “I have no retirement income from previous employment.” Years earlier, she had floated the idea of renting out her second house for extra income, but now she told Cira, “It’s just too much to think about.”

Vojtko needed her meager teaching income to get by, but that was not the only reason she worked into her 80s. “The idea of planning for old age did not happen for her,” says Cira. He says that when he asked once, she said she thought everything would go on as it always had. But Vojtko’s eyesight deteriorated to the point that she could no longer drive. Some of her French students took advantage by cheating on tests, according to Renault. She wore compression stockings to treat blood clots in her legs and walked with a cane (or, preferably, an umbrella, which she thought wouldn’t make her look as old). She tired easily, which made it difficult to walk up the steep hill from the bus stop a mile from her house. Sometimes she would wait in the vestibule of a Walgreen’s and ask strangers if they could drive her home.

Vojtko’s house was also in bad shape. Her roof started falling in, and an out-of-town Slovakian relative who was a contractor offered to fix it as a thank-you for translation help that Vojtko had given his family. He came to Homestead to work on her roof for a few weeks in the summer of 2012, but their relationship quickly turned rancorous when he moved some of Vojtko’s belongings without asking. He and Vojtko fought, and he ended up leaving town with the roof only half-repaired.

In late summer 2012, Vojtko’s cancer came back, and her doctor put her on a new medication regime. She had a bad reaction to one of her drugs, which caused a small heart attack in September. She seemed to be doing better, but then collapsed one day while waiting for a bus. Her friend Victor Fiorina suggested that she stay in his home in downtown Pittsburgh so she could be closer to work. She accepted this offer, but she was frustrated by the lack of privacy at Fiorina’s house, and she moved out after a few weeks. All along, she returned home regularly to feed her elderly cat, Fluffy.

In December, Vojtko’s furnace broke. She piled her bed high with blankets to deal with the cold at night. And she left town to visit her last living sibling, George, in California. He was 91, had been ill for years, and had recently been given a grim prognosis. But Cira says Vojtko “kept saying to me with great, great force, ‘Age means nothing.’ ” George died on Jan. 2, 2013. Vojtko attended the funeral on Jan. 9, and then began teaching her spring semester class five days later.

When she returned to Homestead, her house was freezing, and her cat had died, even though she’d arranged for a neighbor to take care of it.

In his article “Death of an Adjunct,” Kovalik said Vojtko couldn’t afford to fix her furnace because medical bills had left her “in abject penury.” He made it sound like she’d been abandoned by the Duquesne community. In fact, neither was quite true.

Vojtko was due to receive a few hundred dollars from her brother’s estate, which almost certainly would have been enough to fix the furnace. But letting her Slovakian relative into the house had gone badly, and she wasn’t about to open her doors to a stranger now. (“I don’t like people in my home,” she told Cira at the time.) She treated the broken furnace like her eyesight and her mobility—a disability to circumvent. When friends and acquaintances expressed concern, she found ways to put them off.

Photo courtesy Sébastien Renault

Vojtko told Weir, who’d boarded up her windows and picked up her mail during her cancer treatments, that her nephew was coming to fix the furnace’s pilot light. In fact, she hadn’t spoken to her nephew in months. She told other people, such as Kovalik, that she couldn’t afford to have the furnace repaired. She told Cira, who offered to light the pilot for her, that it needed to be repaired. Then she said she wouldn’t call a repairman: “He would see my house, and he couldn’t get down the stairs,” Cira remembers her saying.

Vojtko dealt with her lack of heat at home by sleeping on a sofa in her shared office at Duquesne. A custodian saw her and tipped off the campus police. They offered to drive her home. Vojtko asked to be taken instead to the Squirrel Hill location of Eat’n Park, a local casual restaurant chain open around the clock. She started staying up through the night in a corner booth next to the salad bar, grading papers and editing a Catholic missionary book.

Early each morning, she’d go to her office and sleep for a few hours before her colleagues arrived, but the people who cared about her could see that she wasn’t rested. “She looked bad,” says Cira of this period. “She looked tired and worn out.” Cira offered to buy Vojtko a space heater to use at home as a stopgap measure, but Vojtko said no—she had so much stuff, she explained, that there was no way to get to the electrical outlets.

The police officers who drove Vojtko to the Eat’n Park also offered her information on senior services, subsidized housing, and furnace-repair services. When she refused to look into any of these options, one of the officers asked Dan Walsh, the Duquesne university chaplain, for help. Walsh arranged for Vojtko to stay in a dormitory for a few days in February, and then in a room in Laval House, the priests’ residence on campus. The room was available for a month, pending the arrival of a visiting priest from Africa. Walsh tried to make sure Vojtko would be able to go home afterward. He spoke to his supervisor and got university funds to pay for her furnace repairs. He offered to go to her house so she wouldn’t have to stay home and wait for the contractor. Vojtko said no. When she left Laval House in March, she didn’t tell Walsh or the other priests where she was going, and they didn’t ask. She went back to spending nights at Eat’n Park.

Photo courtesy Alekjds/Creative Commons

The founder of the adjunct union, Joshua Zelesnick, and his wife also tried to help. They invited Professor Vojtko to stay with them. A cafeteria worker at Mercy Hospital offered her a place at his family’s house, too. Two financially comfortable friends of Vojtko’s, a retired judge named Francis Caiazza (who later eulogized Vojtko) and his wife Rosalina, offered her money to fix the furnace. Vojtko wouldn’t take it. “She didn’t want to be a burden,” Zelesnick says.

For Vojtko, the idea of moving permanently was simply unthinkable. “She would tell me that her father always told her that your house is a museum, your own history-of-your-family museum,” says Weir. Vojtko was the last surviving curator. Renault introduced her to a nun who was also a social worker, and who looked into senior housing options for her, but Vojtko feared losing her independence and didn’t pursue them. Cira encouraged her to apply for a subsidized apartment through the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. She refused to fill out the paperwork.

“Every suggestion that a lot of us gave to her was shot down,” Cira summed it up for me. He remembered a conversation he had with Vojtko last Easter. She’d listed five goals for the summer, including getting her health back and writing up her syllabus for the fall—but not fixing her furnace or making her house more habitable. Cira says he told her, “Margaret, I think the world of you. You are my friend. I’m going to say this from my heart: People were very accommodating to you because you were in this bind. If you go the whole summer without securing a place, a lot of people would tend to think, ‘Well, you had all summer!’ ”

He says that Vojtko said she’d worry about heating her house after her other five goals were completed. “You know, I don’t appreciate what you’ve just said to me,” he says she added. He’d been trying to express concern. She made it clear she felt insulted.

A much worse insult was soon to come: Vojtko’s firing on April 2. In lieu of a new teaching contract, Krause and the dean of the college offered her a tutoring job that paid $15 per hour for 10 hours each week—two-thirds of her adjunct pay. After 25 years, she felt she deserved better—even if, as an adjunct, she’d never had any guarantee of future employment at Duquesne. “More than the money, she felt very hurt that they said, ‘We don’t need you anymore,’ ” says Kovalik, who met her shortly after she’d been given notice, at an academic conference organized by Duquesne’s adjunct union. After hearing about her dismissal, Kovalik began helping with her complaint to the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. He thought Vojtko had been illegally fired—or, technically, not rehired—because of her age and disability and that she might be entitled to a settlement.

As Vojtko and Kovalik worked on her EEOC complaint, she found out that her cancer had seriously worsened. Her doctor told her she had six months to live. While she grappled with that news, she had to clear out her desk at Duquesne. Packing and moving belongings is often difficult for people who hoard. It took Vojtko more than three months.

Photo by L.V. Anderson for Slate.

Vojtko had lost her brother, her cat, her heating, her source of income, her office, and her health. But until now, she’d managed to hold onto her independence. She’d long told Cira and Renault she “didn’t want to get trapped in the system”—meaning senior services or, worse, a nursing home. And, despite immense hardship, she still didn’t have to answer to anybody.

Then, in August, Vojtko received a letter from a case worker with Allegheny County’s Adult Services, the local government agency that investigates reports of elder neglect and provides in-home care and counseling to senior citizens. “This letter is to inform you that a Report of Need concerning you has been received by the Allegheny County Area Agency on Aging,” the investigator wrote. The report had been made anonymously. The investigator had already dropped by Vojtko’s house a few days earlier. Now she wrote that if Vojtko didn’t agree to see her, she would be required to petition the Orphan’s Court of Allegheny County for a visitation order.

Orphan’s court is another name for probate court, but Vojtko saw the phrase and panicked. She called Kovalik from a pay phone at West Penn Hospital, where she was going for cancer treatment. “She said, ‘This is humiliating, and this is ridiculous. You call her and you tell her, “Stay off my property,” ’ ” he remembers. Vojtko may have suspected that a social worker would want to come into her house, clear pathways through her piles of belongings, and maybe get a court order to clean out the house. If so, that could only have felt like a deep violation.

Vojtko hung up with Kovalik, faxed him the letter from an office at the hospital, and headed home on the bus. It was a warm day. Maybe she couldn’t find a stranger near the bus stop to hitch a ride from, or maybe she caught a ride partway and then walked the last few blocks, up the steep hill to her house. Vojtko almost got to the top. Her home was almost within view at the moment that she collapsed. As others had in the previous months, people close by tried to help. A man mowing a lawn nearby ran to catch Vojtko before she hit the ground. A next-door neighbor rushed over to resuscitate her, but couldn’t.

When an 83-year-old woman dies in circumstances like these, it’s natural to look for a culprit. Someone, we think, should have done more. In Vojtko’s case, many people tried individually to help her. But did Duquesne, the Catholic institution that employed Vojtko for a quarter century, do enough?

In response to the bad press that followed her death, Duquesne asserted that the university tried. Walsh, the university chaplain, released a statement describing Vojtko’s stay at Laval House and told me in an interview that he was “so proud” of the “quiet” way the university offered assistance to Vojtko. Duquesne’s vice president for university advancement also released a statement defending “the many individuals in our community who, with great compassion, attempted to support Margaret Mary during a very difficult time in her life.” Walsh, and the campus police officers who tried to help Vojtko fix her furnace, certainly fit this description.

The administration’s actions were less praiseworthy, however: Yes, they offered Vojtko money to fix her furnace, but when she refused to fix it and started spiraling downward, they took her job away.

Kovalik has derided Duquesne’s outreach to Vojtko as woefully inadequate. “They simply claim that, in lieu of a living wage and benefits, they offered her intermittent charity and prayers as a salve to her impoverishment,” he told Duquesne’s student newspaper. He argues that university recognition of the adjuncts’ union, and a union-negotiated contract, would have made it much more difficult for Duquesne to fire Vojtko and entitled her to a severance package based on her years of service. And if Vojtko had earned more money and had health insurance and other benefits all along, she might have been able to retire, instead of working into her 80s.

To be fair to the university, though, better benefits and job security would not have altered many of the personal factors that precipitated Vojtko’s crisis. Her hoarding and her deep-seated stubbornness—not her finances—were behind her refusal to get her furnace fixed, or to move to a facility better suited to her medical condition.

In the wake of Vojtko’s death, Duquesne defended its adjunct policies by arguing, essentially, that it’s doing what every university does. The provost, an affable Englishman named Timothy Austin, called me a couple of days after Kovalik’s op-ed went viral. “My response to all of the frenetic email and blogging traffic is that I find it a little puzzling that it is being directed at one institution,” Austin said, “as if somehow other institutions were not confronting exactly the same or almost exactly the same issues.”

But that’s the problem: Virtually every university over-relies on underpaid adjuncts. With less public funding flowing into state and nonprofit universities, universities are more dependent on fundraising and on income from students whose families can afford to pay full tuition. As a result, universities have devoted more money to administrators’ salaries and to fancy perks that make them more appealing to prospective students, and less money to teaching. And with more people earning Ph.D.s—particularly humanities Ph.D.s—than there are academic jobs, it’s easy for universities to skimp on adjunct pay.

Hiring adjuncts instead of tenure-track faculty is unquestionably great for a university’s bottom line. From every other perspective, though, it’s a scourge. This is not just a question of adjuncts toiling away in relative penury. Overworked, underpaid adjuncts are also bad for students: Professors who don’t have their own offices, often must work multiple jobs to make ends meet, and sometimes find out whether they’re teaching shortly before the semester starts simply cannot devote as much energy and time to their students as they would like. Adjuncts are also bad for taxpayers: When universities don’t pay their instructors adequately or give them benefits, adjuncts end up relying on food stamps and Medicaid. And, money aside, adjuncts are bad for universities themselves: Hiring adjuncts anew every semester is inefficient, and managers’ lack of accountability for how they treat these employees leaves them vulnerable to discrimination suits like Vojtko’s. We should expect universities to pay adjuncts a living wage, give them benefits and some job security, and provide them with the resources they need to do their jobs well—especially because we tend to think of education as a public good, rather than just another consumer industry.

Unions are the way toward this goal, according to Gary Rhoades, director of the Center for the Study of Higher Education at the University of Arizona. He told me that unions had recently won higher wages and better job security at George Washington University and American University—two institutions that, like Duquesne, are private, urban, and well endowed. And he pointed me to a recent survey showing that universities with adjunct unions pay 25 percent more on average than universities without them. The study also indicated that unions increase the likelihood that adjuncts receive health and retirement benefits, job security, regular raises, and pay for work that takes place outside the classroom (like office hours and departmental meetings). “Unionization is associated with getting people out of the working poor category … and I think you can see that happening,” Rhoades said. “There’s now beginning to be a reversal as adjuncts more and more begin to organize.”

Duquesne, by contrast, continues to block its adjuncts from bargaining collectively, Kovalik says, despite the negative attention the university has received since Vojtko’s death. Rhoades thinks universities like Duquesne fear unions not only because of money, but also because they stand to lose power—specifically, the managerial flexibility they currently enjoy when it comes to course assignments. Duquesne apparently isn’t interested in using the national spotlight to become a leader in this area of academia—a legacy that Vojtko might have valued more than victimhood.

Duquesne couldn’t have saved Margaret Mary Vojtko, and it can’t singlehandedly save academia from its slide toward corporatization. But it can make life better for its 147 liberal arts adjunct professors—and their students—by recognizing the union and negotiating with it in good faith. Vojtko, in that campus magazine interview a few years ago, contrasted teaching as “a devotion” with teaching as “a source of income.” But seeing teaching as a devotion does not preclude relying on it for income. Teaching can—and should—be both.

Correction, Nov. 20, 2013: This article originally misstated that Margaret Mary Vojtko suffered a heart attack on Aug. 16. She suffered a cardiac arrest. (Return.)