Expats in Asia

BUSAN, South Korea—I've been in the southeastern Korean port city of Busan for two days now, and I have yet to meet a single Korean who is unnerved by the fact that Kim Jong-il has conducted a nuclear weapons test a few hours to the north. The closest thing I've seen to concern comes from a rosy-cheeked college student named Hae-Min, who I meet along the boardwalk at Haeundae Beach.

"The bomb test made me very nervous," she says as we wait in line to buy bottled water from a street vendor. "I was afraid foreign reporters would be scared to come to the film festival." She pauses and smiles, indicating the press pass hanging from my neck. "So, I'm happy to see you here."

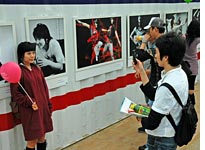

Hae-Min is talking about the Pusan International Film Festival —PIFF for short (the festival started in 1996, when Busan was still transliterated as "Pusan")—and for South Koreans jaded by 50 years of provocations from the North, this event appears to be far more intriguing than the notion of nuclear war. Currently the biggest and most influential festival of its kind in Asia, this year's PIFF boasts 170 feature films from 63 countries. Variety has nearly 20 reporters in Busan to publish a daily from the festival, and over 5,000 industry professionals are said to be in town for the festivities.

Despite my press credentials, however, my motivation for visiting Korea's second-largest city goes beyond an interest in Korean Wave filmmaking or the desire to catch the latest Asian premieres. Rather, I am here because I worked in Busan as an English teacher in the late '90s, and Korean-born U.S. director Wonsuk Chin has written a screenplay about this experience, titled Expats. Since Chin is at the festival, meeting with possible financiers for his film, I've made plans to see him this afternoon at the Grand Hotel.

Chin has been involved with the PIFF organization since its inaugural year, and his first film, Too Tired to Die (starring Mira Sorvino, Jeffrey Wright, and Takeshi Kaneshiro), made its Asian debut here after opening at Sundance in 1998. Three years later, when he came to the festival to promote e-Dreams (a documentary about the celebrated dot-com-era rise and fall of online convenience store Kozmo.com), Chin became fascinated by Busan's expatriate subculture and decided to write a movie about it. In the course of researching the screenplay, the filmmaker came across an article I wrote for Salon about late-'90s expatriate life in Busan, and he and I have been e-mail acquaintances ever since.

Admittedly, Expats is not literally about my life, though I have enough in common with Chin's protagonist Jeremy Keller to feel like it could be. As was the case for me 10 years ago, Keller isn't sure what to do with his life in his mid-20s, so he elects to buy some time (and make some cash) by moving to Korea to teach English. Like I did, Keller finds himself charmed, bewildered, and frustrated with the extremes of expatriate life, as well as the challenges of living and teaching in an unfamiliar culture. Like I did, Keller falls in with an eclectic group of acquaintances, including an international roster of fellow expats.

Unlike my experience, Keller and his expat friends decide to buy black-market guns and rob some Korean gangsters—but I suppose that's how movies work. Chin describes his new film as a cross between Lost in Translation and Lock, Stock, and Two Smoking Barrels.

In his film synopsis, Chin has described Busan as "the modern Casablanca"—a romantic comparison that has aroused some skepticism among current expats in this crowded, workaholic city of traffic jams and concrete high-rises. Still, Casablanca wasn't a romantic city until the movie Casablanca made it into one. Movies have a way of reinventing how places are perceived, and a big reason I'm back in Busan is to get a last look at its foreigner subculture before Chin's movie puts the city onto America's pop-cultural radar.

As I walk along Haeundae Beach to the Grand Hotel, I can see that Busan has transformed since I left Korea to become a full-time writer eight years ago. The most notable change is an elegant white suspension bridge that spans Suyeong Bay (imagine returning to Houston to discover it suddenly has its own Golden Gate Bridge), as well as two new subway lines, one of which connects this beach with the rest of the city. Back in 1998, when PIFF was in its infancy, movies were screened in the gritty port district of Nampodong; now, in an apparent attempt to imitate Cannes, the festival is centered around a hotel-studded stretch of Haeundae Beach—which has itself gone upscale in recent years. The Haeundae I last saw was a bustling tangle of frumpy bars, bathhouses, and motels fringing a half-mile-long stretch of sand; the resort beach has now become a tidy, sanitized strip of luxury hotels and Starbucks franchises, modern-art museums, and aquariums.

For a returned expat like me, the globalized gentrification of Haeundae Beach feels a bit artificial—but I'm sure it's a welcome sight for international film tourists, who might otherwise find themselves bewildered in this manic city of 4.5 million people. Haeundae's cosmetic makeover is no accident: For the past decade, the city government has invested huge sums of money in the attempt to transform Busan into a hub for the Asian film industry. Thanks to the British Invasion-style success of Korean Wave films and soap operas across Asia, this investment is paying off. More than 40 Asian films will be shot in Busan this year, and tourist arrivals for PIFF (mostly from other Asian countries) have steadily increased since the beginning of the decade.

Since Wonsuk Chin is an old PIFF hand, my conversation with him is punctuated with continual introductions to other film-fest regulars in the lobby bar. With a boyish smile, goatee stubble, and a thinning crew cut, Chin looks younger than his 38 years. He puffs on a cigarette as he tells me about plans for his new film.

"Most Americans have strong cinematic impressions of Japan or China," he tells me. "It's easy to imagine samurai, or the Forbidden City. It's not that way with Korea: People think of North Korean military parades—or maybe old M*A*S*H episodes—but nothing that truly represents the culture. Korean Wave films are doing well in Asia, but there hasn't been a substantial American movie filmed here in decades. I want to change that. My movie might be an action comedy, but I want American audiences to absorb a real piece of Korea for two hours."

"So why make a move about expats?" I ask him. "Why not portray something more distinctively Korean?"

"I want to show Korea through an outsider's point of view, because I realize how strange this country must seem to visitors. The teacher expats who come here see Korea in a unique way. They aren't isolated like soldiers or businessmen; they're working right in the middle of the culture. They're young, and they're going through a transitional time of life. They're more likely to throw themselves into new experiences."

"And you think these experiences would include robbing Korean gangsters?"

Chin grins and lights another cigarette. "I'm not writing about a specific incident; I'm just exploring a possibility. But in researching the movie, I saw this as a realistic plot idea. Gangsters in Korea don't carry guns; they use baseball bats and sashimi knives. To gun-culture Americans like Jeremy Keller and his friends, Korean gangsters must seem like an easy target if you want to make a quick buck."

Although the IMDb.com page for Expats lists Chris Klein (American Pie) and John Cho (Harold & Kumar Go to White Castle) in supporting roles, Chin won't tell me who he has in mind to play the Jeremy Keller part. Online scuttlebutt has suggested that Jake Gyllenhaal, Jared Leto, and Ryan Phillippe have been approached for the part, but Chin will only concede that he's in the market for a well-known twentysomething Hollywood actor. "Once we cast the Jeremy Keller role," he says, "everything else should fall into place. I'd like to shoot it in Busan next spring and debut it as the lead film next fall at PIFF."

Chin is still curious about what it's like for an outsider to live in Korea, and he asks me about my own experiences in Busan eight years ago. I tell him I have mixed feelings about my time here, but that I look back on Busan like Ernest Hemingway looked back on Paris—as a "necessary part of a man's education," an essential rite of passage in my own life. Since tens of thousands of Americans have made a similar Korean sojourn in the past decade—and since more than 6 million Americans live as expats—I like the notion that indie filmmakers are trying to capture the American expatriate experience on the big screen.

When Chin excuses himself to go attend a meeting, he asks me how I plan to reconnect with Busan's expat scene. For anyone who's ever lived overseas in their 20s, the answer to this question should be obvious.

"I'm going to hit the bars," I tell him.

Indeed, if Busan is really the modern Casablanca, it's time for me to head out and find the local equivalent of Rick's Café Americain. Walking outside, I hail a cab and head into the city.