This year's Whitney Biennial? In a word: Friendly. You get a foretaste of the new populism at the entrance, where they hand out free audio guides. These are actually teeny digital-audio-file players into which you punch numbers corresponding to artworks to hear the artists talking about them, an irresistible twist on the taped tour scorned by the art elite. Another good-neighbor gesture is the chatty wall copy, which spells out exactly what most museum-goers want to know--what the art's supposed to be about. Then there's the art itself, which is pretty, and the overall vision, which is inclusive, with installations and paintings and photography and movies and videos and Web art--for the first time at the Biennial--and more art from elsewhere in the United States than in any previous Biennial and very little that you couldn't describe to your grandmother. (Hans Haacke and his "Giuliani Is a Nazi" installation is another issue, which Culturebox has already addressed.)

You might think all this is a prelude to a thrashing--Tame new director Maxwell Anderson abandons Whitney's role on cutting edge, and so forth. This is the first Biennial to be assembled by a regionally representative outside committee (its members come from Fort Worth, San Diego, San Francisco, and Boston by way of Queens) instead of in-house curators, most of whom quit rather than work with Anderson, who is thought to be aggressively non-avant-garde. The show feels a little unfocused and fails to get in your face, but so what? There's no good reason to require the premier show of contemporary American art to offend, alienate, or break the rules. In fact, it has always smacked of radical chic to demand this of the Whitney, located in the superfancy Upper East Side of Manhattan and named after one of the great American fortunes. In any case, transgression has become American art's most oppressive cliché. Culturebox was reminded of this when she heard artist Luis Camnitzer explain his installation on the audio guide. The piece itself, The Waiting Room, is a hauntingly lovely, ghostly cell filled with the objective correlatives of enforced tedium--a hopscotch game, broken mirrors. Camnitzer says the work alludes to the former dictatorship in his country of birth, Uruguay. Then he goes on to say that it also expresses his belief that artists are prisoners of the forms of their time--forms they must shatter and reinvent.

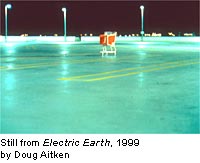

Culturebox suspects that artists are actually prisoners of overwrought theories about having to smash and remake everything. If you agree, then you'll like this Biennial, which is a dreamy person's art show. The works tend toward tactile poetry, often to great effect. There's a disorienting installation called Rain by Leandro Ehrlich, which you duck inside to stand outside of, as it were--standing in the room, you peer out through the kind of windows you'd find on the exterior of a house, and listen to rain falling inside the walls. There's a lush short video called Fervo r by Shirin Neshat, who was born in Iran--a sort of post-revolutionary love story with no words but lots of chanting women's voices, swirling chadors, and long glimpses through dark curtains. Ghada Amer, an Egyptian, has a drippy abstract painting that turns out on closer inspection to be neither abstract nor a painting--it's a series of threads pasted onto canvas that delicately sketch out voluptuous reclining nudes. A room full of jumpy noir-ish video screens by Doug Aitken, who also makes music videos, tracks the meanderings of a young black man through Los Angeles at night. Robert Gober's giant laundry sink has an uncannily realistic pair of girl's skinny legs poking through holes where the faucets should be, clad neatly in socks and sandals--The Shining meets George Segal.

Culturebox's favorite piece is more short story than art. It's an elaborate meta-fiction about a Venetian glass factory called An Historical Anecdote About Fashion. Josiah McElheny, a glass-blower, has modeled a handful of gorgeous colored glass vases after the hourglass figures of Christian Dior's "New Look." Next to the display case is a very convincing but false chronology explaining that they were made in the 1950s by master craftsmen who were taken with the factory-owner's stylish wife after she visited the floor.

There are 157 artists represented in the show, many of them showing films and videos at hours when you'd have to be unemployed to attend. There's no way to summarize the work fairly, and many ways to complain about how there's too much of it. (Click here for an article that does that hilariously.) It's nice to see artists who haven't even made it into galleries yet, and to note that some of the better-recognized work seems far from first-rate: What else can you say about Fort Worth, Texas, artist Vernon Fisher's cracked and aged acrylic paintings on and around which polyurethaned flies have been pasted? The catalog states portentously: "The flies, then, can be seen as switching devices between readings of the painted surface as figure and as ground, as image and as object--or as a straight story with its own comic punch line." Aha! Culturebox had mistaken them for either an easy way to spice up boring paintings or another bad Conceptual joke.

Still from Electric Earth courtesy of Thea Westreich Art Advisory Services, N.Y., and 303 Gallery, N.Y. Photograph of Untitled by Graydon Wood, courtesy of Robert Gober. All rights reserved.