Malta: 10 Days, 6,000 Years of History

A pedestrian casually walking down Triq ic-Cimiterju in the town of Paola might easily walk right past one of Malta's greatest treasures unawares. The entrance to the Ħ al Saflieni Hypogeum is housed in an unassuming structure on a quiet residential street. The site was discovered in 1899 by construction workers digging a foundation for a new home. They kept their find a secret for three years, fearing it might threaten their work. They were right. They had stumbled upon a well-preserved, architecturally sophisticated underground temple containing the remains of 7,000 human beings, members of the mysterious society that flourished on Malta 5,000 years ago.

The prehistoric Maltese population probably came to the island from Sicily circa 5000 B.C. Around 4000 B.C., they started building temples and continued doing so for 1,500 years, when the society disappeared, for reasons that remain obscure. Their structures, however, were built to last: In addition to the subterranean Hypogeum, a series of above-ground megalithic temples dot the Maltese countryside, their names as wonderfully strange as the places themselves: Ggantija, Hagar Qim, Hal Tarxien. These temples, made of massive stone slabs, are among the oldest freestanding structures on Earth. The oldest predate the Egyptian pyramids and even Stonehenge.

The Hypogeum appears to have been a sanctuary as well as an ossuary, a place of worship and a repository for the dead. Because of its fragile state, access is limited to just a few small tour groups each day, making the Hypogeum Malta's toughest ticket. We scored a last-minute pair and descended into the underground temple with 10 other tourists on a rainy Tuesday morning. The chambers were dank and faintly lit, but even in the low light we could make out the spiral paintings on the walls, made in red ocher. Compared with the cave paintings in Chauvet , France, the artwork here is neither particularly impressive nor particularly old. But the space itself is astounding. The Hypogeum is a labyrinth of interconnected chambers covering 5,000 square feet and delving 35 feet into the earth, its three levels carved out of the rock using the most rudimentary of tools: stone hammers and antler picks. In a clever bit of legerdemain, the Hypogeum's prehistoric planners used sculpture to create architectural effects, hewing linteled doorways out of the stone, which give the underground chambers the look and feel of the above-ground megalithic temples with which they must have been associated in some now-lost ceremonial symbiosis.

The remains buried here have long since decomposed or been removed for study, but it is still eerie to walk through what is essentially a mass grave. Death, again, had joined us for a tour, and though he politely trailed behind the group, listening attentively to the thorough audio guide, his presence could be felt in the damp chill of the catacomb. There is no continuity between the prehistoric society that produced the Hypogeum and the itinerant knights who came to Malta 4,500 years later, but exploring this ancient crypt, a link between the two societies occurred to us: Both arrived on this hard outpost in the Mediterranean and set about building magnificent repositories for their dead, in whose company both groups seem to have preferred to worship.

Death had clearly weighed heavily on the minds of the men who built Malta's great churches. At the Co-Cathedral of St. John, fallen knights are interred below the tombstones that make up the church's floor, and Caravaggio's massive, graphic depiction of St. John's murder dominates the church's oratory. Around the corner from the co-cathedral is the shabbier, less-trafficked, yet still imposing Church of St. Paul's Shipwreck, which displays relics of Malta's patron saint. Beside the altar resides a sculpture in the shape of a human hand and forearm. A small glass window cut into the arm reveals a human bone, said to be the wrist of St. Paul. Nearby stands a pillar, alleged to be the one on which Paul was beheaded. A sculpture of the evangelist's head lies atop it, staring absently in the direction of the congregation.

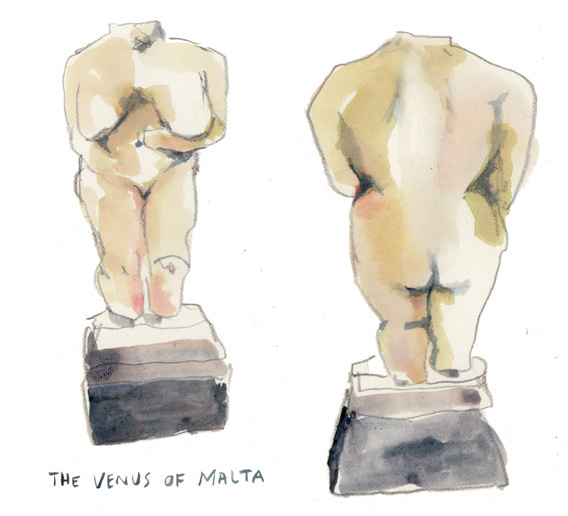

The artifacts discovered at Malta's prehistoric sites and now on display at the Museum of Archaeology in Valletta are similarly tied up with mortality—like the knights, whose elaborate tombstones reminded the living of their worldly achievements and titles held, the prehistoric Maltese buried their dead with items that may have signaled their social status—stone pendants made of greenstone, which isn't local to Malta, have been found in the Hypogeum. But other artifacts seem more concerned with fertility than death. Like many prehistoric cultures, the first settlers on Malta left behind Venuses, small statuettes of female figures with generous proportions.

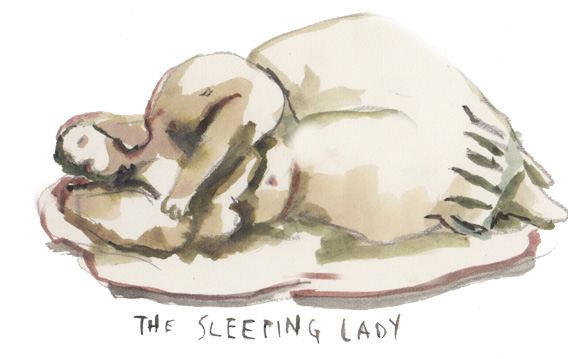

One of them, the so-called Sleeping Lady, discovered in the Hypogeum, reclines on her side in a blissful rest, whether for eternity or merely for an after-lunch nap we'll never know.

In the middle of our 10-day trip, we hopped on a ferry and took the short ride over to Gozo, Malta's smaller, more pastoral, more charming sister island. More charming to us, at least. Residents of the big island expressed shock when we spoke of our affection for the Gozitans. A schoolteacher we met described the nefarious tactics of Gozitan children, who study diligently for their exams, then affect an air of lassitude in order to lull their Maltese peers into a false sense of relative preparedness. The Gozitans we met demonstrated no such cunning: More than one elderly gentleman, coming upon two American tourists bewildered by Gozo's winding streets, offered us directions unbidden, something that never happened on Malta proper. And on our first night on Gozo, when we missed the bus from the ferry terminal to town, the affable driver of a private coach that had just disgorged a group of gussied-up Gozitans headed to Malta for the night agreed to give us a lift to our hotel, notingpoints of interest—important churches, a defunct heliport—along the way.

Gozo is also home to some of the country's best-preserved prehistoric ruins. On an overcast afternoon, we took in the Ggantija temples, so-named because it was once believed that the massive stone structures were left behind by a race of giants. The proposition seems less ridiculous when you behold the temples in person and try to imagine how a primitive society might have levered the enormous slabs into place, and in such a fashion that they would still be standing 6,000 years later.

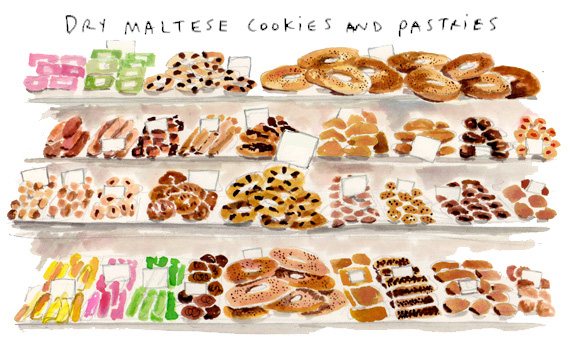

We were still processing the enormity of that feat when we walked from the temples, on the outskirts of Xaghra, to Gozo's largest city, Victoria, where we treated ourselves to one of the great accomplishments of our own era: the McDonald's cheeseburger. We'd tried in earnest to give the local cuisine a fair shake, but at this point in our trip, we'd had our fill of the cheese pastries and meat pies that pass for midday aliment on Malta. Sometimes the carb load and sodium infusion provided by two cheeseburgers, fries, a Diet Coke, and a hot fudge sundae is just what the fatigued sightseer needs to replenish his stores and gear up for an ambitiously scheduled afternoon. A visit to a Maltese McDonald's was also a chance to marvel at the corporation's remarkable ability to reproduce its staples with impressive fidelity the world over, while at the same time taking account of the local palate. (Pistachio shakes!) By the end of our trip, we'd visited four different McDonald's branches on five separate occasions, each meal more delicious than the last.

Being unabashed Americans, we also felt obliged to pay a visit to our culture's other outpost on Malta, the Popeye Village Fun Park. One morning, we took the bus to the northwest of the island, where Robert Altman's crew had erected Sweethaven, the life-size village set for the 1980 film Popeye. It was a cool, wind-whipped day, and the Popeye-themed amusement park that now occupies the set was all but deserted. A smattering of rides for small children had been erected next to the village proper, and the various town structures had been converted into shops, snack bars, a small petting zoo. The craftsmanship of the set impressed us, as did the sheer absurdity of its continued existence. But this was a sad, dark place. To our disappointment, not a single spinach vendor plied its streets, though there was a group of energetic Maltese teenagers dressed as Popeye, Olive Oyl, and Bluto. In the village square, they performed a hard-to-follow masque for a handful of forbearing parents and confused children. Naturally, the action ended with Popeye defeating Bluto and winning Olive Oyl's heart. Later, however, while touring Sweethaven's ersatz dentist's office, we observed some fleeting, flirtatious horseplay between the actors, who seem to have thought they temporarily had the square to themselves. It pains us to say it, Popeye, but you're wearing the horns. Olive's real affections are for the boy playing Bluto.

Tomorrow: Odysseus slept here.