Malta: 10 Days, 6,000 Years of History

Malta is a predominantly Catholic country, and the faith pervades island life.Even tiny Maltese villages can be home to vast, magnificent churches. Many Maltese homes have glassed-in niches near their front doors displaying painted busts of Christ or the Madonna; walking down a residential street, one rarely goes unobserved by a member of the Holy Family. The interiors of the municipal buses we rode were adorned with stickers proclaiming the Lord's magnificence. The drivers, meanwhile, operated their antique coaches as if assured of a place in the Kingdom of Heaven, hurtling through Malta's narrow streets at breakneck speeds, the road before them rarely capturing their full attention. On one occasion, we watched a driver navigate the winding, climbing road to Mdina by steering with his knees, his left hand occupied by the cellphone into which he was chatting, his right hand tasked with delivering some sort of Maltese hoagieto his mouth during breaks in the conversation. (Malta's ancient bus fleet was recently retired, replaced by new vehicles made in China and operated by a German company.)

Ostensibly, at least, Maltese society is as conservative as its faith would suggest. Among E.U. member states, Malta has the smallest percentage of women in the workforce, a fact that's evident when you visit its cities during the day—the men are at work, and the women are keeping house, sweeping stoops or hanging laundry out to dry.

Malta is also one of only three countries where divorce is illegal (the others are the Philippines and the Vatican). Divorce, however, has lately been the subject of heated debate in the country, culminating in a nationwide referendum on its prohibition. The church lobbied strenuously to keep the ban in place. In the days leading up to the May vote, Malta's bishops issued a strongly worded open letter to their parishioners. The letter stopped short of telling the flock how to vote but reminded them that "[t]he Christian must always act with reference to our Lord Jesus Christ and his teachings. In taking his decision on how to vote, he must bear in mind that he shall be accountable to Jesus for his choice." Fifty-two percent of voters decided they'd take their chances with Jesus. The referendum is nonbinding, but Malta's prime minister, Lawrence Gonzi, who opposed divorce, has said he will respect the outcome nonetheless. Parliament took up debate on a bill legalizing divorce in July.

Malta, it turns out, is not exactly the monastery of the Mediterranean. (Nor was it when the supposedly monastic Knights of St. John ruled the island: When a 16th-century grand master tried to banish the island's prostitutes, a riot broke out among the knights.) We visited Malta during the Easter holiday and thus got to see how the island celebrates one of the holiest days on the Christian calendar. The answer: by partying. At least in Cospicua, Vittoriosa, and Senglea—the old fortified cities known collectively as the Three Cities—the vibe was festive, raucous, lightly debauched. On Easter morning, church bells rang out, and the Maltese filled the pews of the country's 365 churches and chapels. But after Mass, it was time for a celebration that, to the American eye, looked less like Easter than St. Patrick's Day.

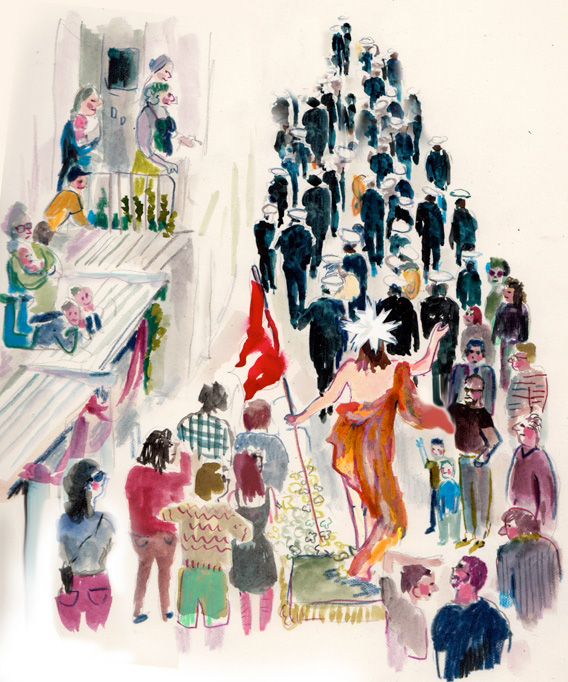

We arrived in the Three Cities in midmorning, too late for church but in time to see one of the processions that are the centerpiece of Easter celebrations across the country. If you've visited New York's Little Italy during San Gennaro—or seen The Godfather: Part II—you've witnessed a similar scene: Locals lined a narrow thoroughfare as a brass band and assorted grandees made their way down the street. Then, a Maltese twist: A group of able-bodied young men hefted a litter that carried a life-size and quite heavy-looking statue of the risen Christ. But rather than slowly, piously making their way through the crowd, they took off at a sprint, running down the street at top speed as their countrymen cheered them on. After a mad dash of about a hundred yards, Jesus bouncing precariously on their backs, the men slowed then stopped, and the crowd rushed to encircle them. Parents jockeyed for position and hoisted young children up to Jesus so that he could bless their Easter toys. The wide-eyed children clutched their new acquisitions warily as their parents maneuvered them toward the holy effigy.

It was about 11 a.m. by this time, and, it should be noted, the drinking had already begun. Chasing after the statue of Jesus, the crowd left behind a colorful detritus: homemade confetti fresh from the paper shredder and empty tall boys of Malta's domestic lager, Cisk (pronounced chisk), whose ubiquitous canary-and-red packaging is an unofficial emblem of the country. A local cafe we ducked into had been converted into a makeshift bar, serving up Jack Daniels in plastic cups to boisterous Easter revelers. (A request for a virgin O.J. was met with a quizzical look.) Maltese homes are known for their beautiful doors, which are often painted bright colors and feature large, distinctive knobs. Walking through Cospicua after the procession, we came upon three young men clustered around a particularly lovely example. They were urinating on it.

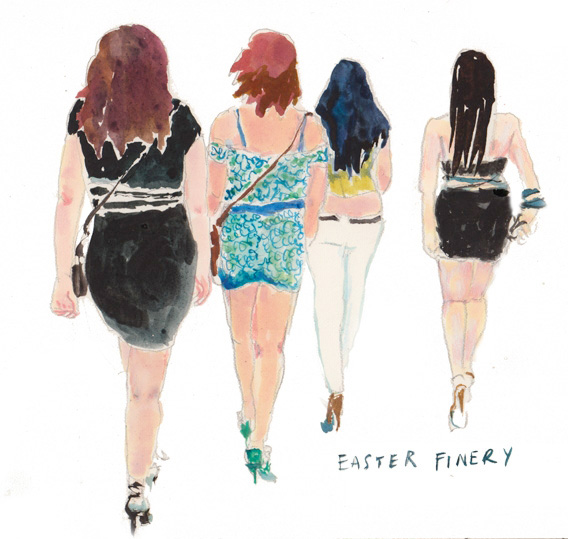

We milled about among the Maltese as they drank their Cisks, ate hamburgers served up from food trucks, listened to house music thumping out of taverns and apartment windows, and generally checked one another out. The locals were decked out in their Sunday best, which in the case of many of the young women looked conspicuously like their Saturday night best—short, tight skirts; plunging halters; heels few American women would dare on streets so rutted and irregular. This wasn't the hallowed affair we'd anticipated, but cheers to that.

In the evening, we returned to our hotel, feeling that particular wooziness that attends ante-meridian drinking. Flipping on Television Malta, we were delighted to find Norman Jewison's groovy 1973 film version of Andrew Lloyd Webber and Tim Rice's JesusChristSuperstar just getting under way. To our knowledge, Malta's bishops haven't issued any encyclicals on the propriety of broadcasting the film on such a holy day, though surely they don't approve. The film takes shocking liberties with the gospels, turning Jesus into a self-pitying sad sack, Judas into a tragic hero, and first-century Jerusalem into a dusty outdoor disco. But watching Josh Mostel's mincing, sybaritic King Herod asking Jesus to liven up the party by turning his water into wine somehow felt like the perfect conclusion to an unexpectedly boozy Easter Sunday.

A few days after Easter, we visited one of the grandest of Malta's grand houses of worship, the Church of the Assumption of Our Lady, better known as the Mosta Dome. (The church features one of the largest domes in the world.) Though built more recently than the cathedrals of Mdina and Valletta, Mosta already has its own mythology and has found its way onto the tourist's to-do list. During World War II, Malta was heavily bombarded by the German and Italian air forces, in what is referred to as the second Siege of Malta. Like so many European powers over the course of history, the Axis sought to control Malta because of its strategic location in the Mediterranean, but as was the case in 1565, the tiny island proved more resilient than its attackers anticipated: Two years of bombardment failed to break the Maltese spirit or defenses, and the Axis eventually abandoned the campaign. (King George VI awarded the George Cross to the Maltese people for their bravery.) It was during the second siege, on April 9, 1942, that the miracle of Mosta occurred. A Luftwaffe bomb was dropped on the church and pierced the dome, falling into the sanctuary as 300 parishioners awaited an evening mass. But the bomb failed to detonate, and the church and its faithful were spared.

We filed into the church on a Thursday afternoon at 3, when it reopens to the public after the generous postprandial break observed by Malta's businesses and institutions. Looking up at the mesmerizing ceiling, you can see where the bomb broke through the dome, and a gang of tourists fanned out amid the pews and trained their telephotos on the plastered-over spot. Our eye was caught, however, by a more mundane miracle: an elderly Maltese woman, sitting in one of the pews, her head bowed in silent prayer, completely unfazed by the swarm of tourists flitting about the church, chatting and bumping into things because they're staring at the ceiling and asking for directions to the gift shop so they can see the scale replica of that merciful Luftwaffe dud.