A Nuclear Family Vacation

Click here to see a slide show.

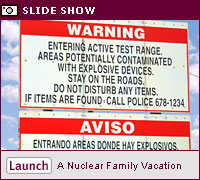

The sentry looked at us sympathetically but shook his head no: We wouldn't be allowed to use the portable toilet on the other side of the gate until our security escort arrived. This was, after all, not just Trinity, site of the first atomic bomb test, but also White Sands Missile Range, an active Army facility. Rules were rules.

We climbed back into the rental car and prepared to wait. We had made the 90-minute drive down from Albuquerque to go on an escorted tour of Trinity, but we were distracted from our lofty historic reflections by more mundane needs.

There was nothing to do but settle back, watch the PowerBars melt, and discuss a different matter of historical importance: Where was Harold Agnew on July 16, 1945, the day the United States detonated the world's first atomic device?

Agnew, a former director of Los Alamos National Laboratory, is one of a handful of Manhattan Project veterans still alive today. According to several of his colleagues, Agnew was one of those present at Trinity.

By any measure, that July 16 was a momentous date. The funny thing is, Agnew himself insists he wasn't there.

"I was at Tinian, getting ready for Hiroshima," Agnew said, when we finally reached him at his home in San Diego.

One of Agnew's colleagues from the time, Lawrence Johnston, sent us a personal photo of Agnew on Tinian, standing outside a Quonset hut and holding the plutonium core for the Nagasaki bomb with a thermometer sticking out of it. (The plutonium remained several degrees above ambient temperature due to its slow radioactive decay.)

Johnston was the only scientist who personally observed Trinity, Hiroshima, and Nagasaki. On the day of the Trinity test, Johnston was on board a B-29 bomber loaded with scientific instruments that circled 25 miles out from ground zero. According to a memoir Johnston wrote in the 1980s, Agnew was on board that plane, along with a few other scientific observers.

Wolfgang "Pief" Panofsky, founder of the Stanford Linear Accelerator Center, was also aboard the instrumentation plane, and he, too, thinks Agnew was there.

"Well, there's total confusion," Panofsky told us at his office in Menlo Park, Calif. "Agnew said he wasn't at Trinity. But Luis Alvarez in his book says Agnew was at Trinity. And Larry Johnston, who was at Trinity, wrote an article in another book that says [Agnew] also was at Trinity."

In any case, Panofsky said, "The vote is 2-to-1."

Agnew's take on all this? Memory is fallible, particularly among octogenarians.

"Don't grow old," he warned us.

It seemed odd at first that some people might not agree on the details of such an important event. After all, Manhattan Project Director Robert Oppenheimer, ready with a portentous quote, recalled a line from the Bhagavad Gita after witnessing the test: "Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds."

But the average scientist was just happy the thing worked, according to Johnston.

"My immediate reaction was, 'Well, thank God my detonators worked!' " he said. "Because that was a component. And you know if it had failed, I would have said, 'I'll bet my detonators failed.' And I suspect that everybody that had responsibility for some component of the bomb would have had the same feeling: 'Oh my golly, it's my fault.' "

But the failures of memory underscored a broader point for us: Most of the survivors of the Manhattan Project remembered very specific details about their work, but not necessarily how they felt about entering the atomic era. Panofsky, for instance, said most participants were preoccupied with their task.

And as we found, Trinity is not a place that automatically lends itself to profound thoughts about the nuclear age. About 45 minutes after we parked at the Stallion Gate, two cheerful Army officials arrived to take us down to the Jornada del Muerto (often translated as the "Journey of Death"), the remote valley where the test took place. Accompanying us were a Japanese camera crew and a Fox News team from El Paso, Texas. The San Francisco Opera, which is readying a production called Doctor Atomic, didn't make it that day.

The site is itself somewhat ahistorical. The obelisk marking ground zero was made from local lava for no particular reason, and a plaque acknowledges White Sands base commander Maj. Gen. Frederick Thorlin, whose only contribution, our escorts acknowledged, was "chipping in the money" for the memorial erected in 1965.

And for years, no one knew what do about Trinitite, radioactive remnants of sand that the bomb melted into glass. Until recently, the eerie bluish-green rocks sat unprotected around the site, disappearing into the pockets of tourists. Now a bunkerlike structure sits opposite ground zero to protect a few pieces for future generations.

Even the surrounding grounds seem out of place. Signs tell visitors to beware of oryx, an African big-game species that the state of New Mexico introduced for trophy hunting.

Today, the site is safe for visitors, although it's still slightly radioactive. Yes, the radiation is "above background," said Debbie Bingham, our Army escort, but visitors wouldn't be let in if it weren't safe.

"After all, we're the government," she said without a hint of irony.

Asked if the government took any precautions during the Trinity test to protect the attendees, Agnew burst out laughing.

"They didn't do any of that crap in those days," he said.

The survivors of Trinity have all gone their own way. Johnston, who describes himself as an evangelical Christian, isn't much interested in philosophical issues of arms control—he's into intelligent design theory. Agnew seemed ambivalent about nuclear weapons reduction but offered a provocative suggestion: Every few years, the world's leaders should witness a thermonuclear test, preferably in their shorts, to experience the tremendous heat.

Panofsky smiled at the mention of Agnew's suggestion, agreeing with the principle behind it. People forget, he said, that nuclear weapons are not just more powerful than conventional ones, they are more powerful by a factor of about a million.

They forget the heat that melted the sand at Trinity; they forget the blasts that knocked down make-believe houses at the Nevada Test Site; and they forget what Linton Brooks, the head of the nuclear weapons complex, told us back in Washington: "Sept. 11 was a horrible day, but there's a lot of difference between 3,000 people and 100 million people."

Terrorism is bad, Brooks continued, but nuclear annihilation is far worse.

Sitting in Panofsky's sunny office in Northern California a few days after our visit to Trinity, perhaps we, too, didn't quite get it.

The eminent physicist shook his head slightly and said, "People talk about it, but they don't feel it in their bones."

Endnote: Trinity, where the world's first atomic device was detonated on July 16, 1945, is open to the public twice a year, on the first Saturdays of April and October. The public will also be able to visit on the 60th anniversary of Trinity, and White Sands has provided dozens of new portable toilets to prepare for what it thinks might be the largest public day yet. For more information, contact the public affairs office at White Sands Missile Range.