Choctaw Bingo

A modest proposal for a new national anthem.

It's rare for me to devote an entire column to a single song—although I once did so for Joni Mitchell's "Amelia" —but in this case it's a song by a singer whose name is not very well-known and whose name I want to make known.

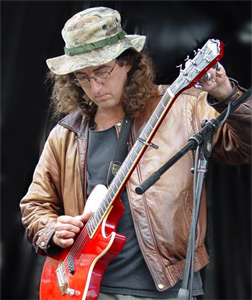

His name is James McMurtry, and that—his name—initially presented an obstacle to my appreciating his work. I've been intrigued by McMurtry ever since my girlfriend came back from a trip to the far reaches of inner America. She'd heard this song—and other great McMurtry cuts—while driving long stretches of West Texas and Oklahoma. When she played me McMurtry's masterpiece "Choctaw Bingo," I couldn't stop thinking about it.

A lot of this not-very-well-known Texas-based singer-songwriter's work is great (start off with Best of the Sugar Hill Years; his latest is Just Us Kids). And I'd call "Lights of Cheyenne" one of the most beautiful visionary romantic ballads I know. But "Choctaw Bingo," released in 2002, is genius. It's more than just genius; it's prophetic genius. New-national-anthem-level genius.

Seriously. It's time to retire ol' Francis Scott Key's "The Star-Spangled Banner" and go with a song that more truly represents the America of today: post-crash, pre-apocalypse, meth- and money-addicted, heading down the highway to self-destruction.

To return to the "problem" of McMurtry's name. It's not surprising, of course, that McMurtry can write: He's the son of Larry McMurtry, the author of classics such as Lonesome Dove. (And his mother was an English professor, a complex burden we share.)

But being a devotee of truck-stop rock, I found myself wondering whether James McMurtry—the bard of what he calls "the North Texas-Southern Oklahoma crystal methamphetamine industry" country, the man who seems to capture its hard-bitten, sin-ridden nuances so faithfully—could really be the real thing. Yes, his father is Texas-born, it's true, but he also published often in the New York Review of Books, and I had a notion this would somehow disqualify his son from raw, unadulterated Texas-Oklahoma authenticity.

You can see, though, with just one twist of the DNA, how the son can bring the father's literary talent to the outlaw country/redneck rock genre; he writes songs with the kind of offhanded quick wit and painfully bitter, cut-to-the-bone romantic remorse with which geniuses like John Hiatt, Kris Kristofferson, Steve Earl, Robert Earl Keen, and Rodney Crowell made their names. Rosanne Cash and Emmylou Harris sometimes hit that note of highway melancholy, too. *

Hangover wisdom, truck-stop soul, stolen-car drive tunes: It's hard to give the genre a name. It's not pure country, and it's not pure rock (though it totally rocks). Anyway, McMurtry's best songs stand up to the best of his cohort. He's a kind of cult- and critics' fave who hasn't yet broken out of the "Americana" box.

But he's got the talent for it. And he's a prophet, too. He was writing songs about subprime mortgages and meth-crazed good ol' boys back in 2002, when he released "Choctaw Bingo," the best of these. The song is my candidate for new American anthem, a national anthem for the crash, because it captures a culture where addiction to meth and addiction to money are indistinguishable in their frenzy and their ruination. Vice versa and vice worser. If you don't hear it the first time you hear "Choctaw Bingo," you've spent too much time on the coasts and not enough in the off-the-grid, flown-over locales.

How shall I describe "Choctaw Bingo"? It's about a family reunion in heavy meth country convened by mean old "Uncle Slayton," who's a kind of malignant Uncle Sam figure for the assembled family members.

Here's Uncle Slayton's making a transition from selling moonshine to cooking meth:

Sells his hardwood timber to the chipping mill

Cooks that crystal meth because the shine don't sell

He chooks that crystal meth because the shine don't sell

You know he likes his money, he don't mind the smell.

"Likes his money, he don't mind the smell": Any difference here between Uncle Slayton and the white-shoe investment bankers who knew the stench of the toxic derivatives they were cooking up but were only too happy to keep the addled customers satisfied?

And Choctaw bingo itself is one of a number of Indian reservation enterprises, tax-free reservation-land smoke shops and the like, that inhabit the song. These phrases, the song's setting, call to mind a land that still bears evidence of its stolenness, the reservation culture and naming practices that still evoke the tragic history of the tribes. The song reminds me of Robert Lowell's "Children of Light," that insidiously malevolent poem about the Pilgrims' original theft from the "Redmen."

First, we hear from one of the pilgrims to the family reunion. (Yeah, there's a "Canterbury Tales" shadow structure going on here.) This is a guy named Roscoe who:

... stopped and bought a couple of cartons of cigarettes

At that Indian Smoke Shop with the big neon smoke rings

In the Cherokee Nation hit Muskogee late that night

Somebody ran a stoplight at the Shawnee Bypass

Roscoe tried to miss 'em but he didn't quite. ...

Whoa, careless slaughter on the Shawnee Bypass! The lyrics lope over it, but the blood and guts spilled on the concrete make this reunion a bloodstained occasion from the get-go. Great line: "Tried to miss 'em but he didn't quite": The vast carelessness of the roadkill in Gatsby almost finds an echo in the offhandedness of "didn't quite" here.

And then there's Choctaw bingo itself, which evil Uncle Sleyton "plays every Friday night." Here's an ad for Choctaw bingo that heads the Google search list, probably a sponsored link:

Experience the thrilling and rewarding fun of Indian bingo at Choctaw Casinos! Choctaw Bingo has been one of the premiere high stakes bingo halls since 1987. Choctaw Bingo features 750 seats, giant video projection screens, and a non-smoking section. Choctaw Bingo hosts monthly High Stakes Bingo Games for that bingo player who likes the Big Money. Our friendly staff is always willing to help any customer. So, whether you're a beginner or a seasoned veteran, Choctaw Bingo is the place where winners play.

Overnight packages available on weekends. For reservation information call 1-800-788-BINGO.

Sounds classy, right? No doubt "winners" play there all the time.

Now, I have a thing about Indian casinos. I'm totally in favor of them. I think they're a disguised form of reparations for the theft of Indian land. I'm glad the tribes are making billions taking the foolish white man's money. They deserve it. No tribe more than the Choctaw because it was their removal from their homeland that gave birth to the phrase "trail of tears."

Yes, it was the Choctaws who signed a treaty in 1831, the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek (no joke), which led to a forced march, a death march, really, in thousands of cases. From Mississippi (which, in their absence, became the meanest, most repulsively racist state in the nation) to the drylands of Oklahoma, where they scratched out a living until casinos were legalized.

Now, the Choctaws get their revenue from meth-and-moonshine-addled fools who play Choctaw bingo, which somehow, despite the 750-seat auditorium and "giant video projection screens," doesn't seem a sure route to financial stability. (But just as sure and stable, it turns out, as collateralized mortgage obligations.) The more you look at the history of the Choctaw nation and how the "trail of tears" led to Choctaw bingo, the more a kind of allegory the song becomes, an eloquent distillation of the tragic history of the American empire, which was based on the theft of land the nation was founded on, the murder and the enslavement of the tragic remnant of the original inhabitants, and their sly, delayed revenge (Choctaw bingo). The more you know about the Choctaw "trail of tears," the more you suspect it's no accident that McMurtry chose Choctaw bingo as his emblematic game.

Here's where this song is so amazingly prophetic. Looking at it now, through the lens of the crash, you can see how it envisions the American economy as nothing more than an elaborate Choctaw bingo enterprise, with lots of flashing lights to lure in the unwary and the unlucky, a system that, for all its fancy formulas and talk of risk assignment, is nothing more than a sucker's game. And later in the song, McMurtry explicitly names the scam at the heart of it: subprime mortgages.

'Cause here's Uncle Slayton running the subprime scam:

Uncle Slayton's got his Texan pride

Back in the thickets with his Asian bride

He's cut that corner pasture into acre lots

He sells 'em owner financed

Strictly to them that's got no kind of credit

'Cause he knows they're slackers

When they miss that payment

Then he takes it back.

It's the subprime mortgage crisis bubbling away as far back in 2002, because Uncle Slayton's bad-credit-no-credit mortgages are probably still "bundled" inside the inside of the inside of some bad bank's lowest tranche of toxic derivatives.

How'd he do it, McMurtry, paint that vision of hell with the money and methamphetamine, mixed in with highway mayhem and the mortgage crisis and the whole "family reunion" heading for a violent crash? No accident all the talk of guns in the song, either:

Bob and Mae come up from a little town

Way down by Lake Texoma where he coaches football

They were two-A champions now for two years running

But he says they won't be this year, no they won't be this year

And he stopped off in Tushka at that "Pop's Knife and Gun" place

Bought a SKS rifle and a couple a full cases of that steel core ammo

With the berdan primers from some East bloc nation that no longer needs 'em

And a Desert Eagle that's one great big ol' pistol

I mean .50 caliber made by badass Hebrews

And some surplus tracers for that old BAR of Slayton's

Soon as it gets dark we're gonna have us a time

We're gonna have us a time.

Note the football amidt the gun slang. But this is no Friday Night Lights. There's no tender Texas sophistication here. This is a meth-fueled arms-dealing collection of troublemakers heading for a shootout with a not-accidental evocation of Serbia and Palestine giving it world-historical weight.

It reminds you of what a blazing shootout our original national anthem was, with all that rockets'-red-glare. Only we've got a new one now, my choice for a new national anthem, and McMurtry's is better than Francis Scott Key's tortured jingoism, if you ask me. No, I can't see people standing up at a ballpark, hands over hearts, hymning their joy at Uncle Slayton's subprime meth dealing. (This is a "modest proposal," people: Jonathan Swift wasn't really advocating the starving Irish eat their babies, OK?)

But when I first heard that song in my girlfriend's car, I thought to myself, "Wow! This guy has really caught America in the Thelma and Louisemoment before it goes off the cliff." And it's even got the equivalent of "The Star-Spangled Banner's" emblematic flag.

There's a passage in the song about two hot chicks who arrive for the reunion:

Ruth Ann and Lynn come down from Baxter Springs

That's one hell-raisin' town way up in Southeastern Kansas

Got a biker bar next to the lingerie store

That's got them Rolling Stones lips up there in bright pink neon

And they're right down town where everyone can see 'em

And they burn all night

You know they burn all night

You know they burn all night.

Yes, McMurtry's "Choctaw Bingo" is an anthem for the crash, because we may be going down in flames. But those bright pink neon lips burning all night are like the rockets' red glare: "proof through the night that our flag is still there." Those neon lips still wave o'er the land of the brave and the home of the biker bar (lingerie store attached).

Correction, March 18, 2009: This article originally spelled Robert Earl Keen's name incorrectly. (Return to the corrected sentence.)