What Was “Gradual Emancipation”?

Even in the Northern states, slavery’s abolition arrived slowly after America’s Revolution.

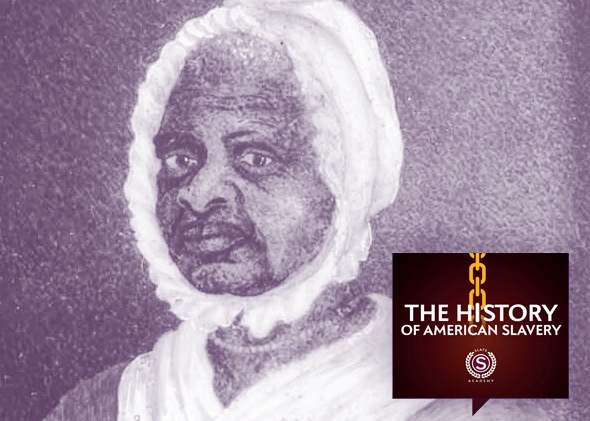

Illustration by Slate. Painting by Susan Ridley Sedgwick via Wikimedia Commons

This is a free excerpt of The History of American Slavery, our inaugural Slate Academy. To listen to Episode 3 in its entirety, visit the show page.

To access all features of this Slate Academy, and to learn more about enrolling, visit Slate.com/Academy.

Subscribe to our preview feed to listen to other free excerpts from The History of American Slavery.

Episode 3 guests referenced in this preview:

Emily Blanck, associate professor of history at Rowan University and author of Tyrannicide: Forging an American Law of Slavery in Revolutionary South Carolina and Massachusetts.

Douglas R. Egerton, professor of history at Le Moyne College and the Merrill Family visiting professor of history at Cornell University; author of Death or Liberty: African Americans and Revolutionary America.

Enroll now in a different kind of summer school. Slate’s Jamelle Bouie, Rebecca Onion, and our nation’s leading historians on our foundational institution. Included in your Slate Plus membership!

The following transcript has been lightly edited for clarity.

Jamelle Bouie: So, Emily Blanck mentions “gradual emancipation acts.”

And what those were, instead of someone being emancipated free immediately, the state would say to their owner, “From this period to this period, they are an apprentice, they are beholden to you, but after that period, we’ll essentially wean you off them.” And then they’re free.

For children it would be something like 18 to 21 years, from their childhood to the beginning of their adulthood, you have them—and then they’re done.

And what’s interesting, in the 1850s, Lincoln was sort of a fan of this kind of thing. Of compensated emancipation, of colonization, of ways to end the institution of slavery without making it too hard on the slave owner.

Rebecca Onion: Yes, so that makes me wonder if Lincoln was looking back at the kinds of legislative actions that Northern states took after the Revolutionary War, as sort of a model for his thinking on this subject.

And actually this was one of the things that surprised me the most about looking into this topic, is that, I’m pretty sure in no case was there a law passed that immediately said, “Everyone is free.”

States passed gradual emancipation acts and in some cases didn’t pass them until much later. Emily mentioned, for example, that New York passed a gradual emancipation act in 1799, and New Jersey was the last one to pass it in 1804.

And the result of that, with all of the clauses that those acts had, was that there were still slaves in New York in 1827 when the state finally abolished slavery entirely, and in New Jersey there were actually slaves remaining in slavery by the time of the Civil War. Which was kind of amazing of me.

Bouie: It’s really crazy to think of New Jersey as a place that had slavery for its entire antebellum history.

Onion: Yes, in sort of pockets and places, right?

Bouie: Of the Northern states, which of them had the most radical approach toward gradual emancipation?

Onion: Emily did mention that Pennsylvania—good old Pennsylvania, as always—passed an early gradual emancipation act in 1780. And there also was a provision that said that, anyone who brought a slave into the state and stayed more than six months, that enslaved person would be considered free.

She mentioned by way of anecdote that when George Washington was president of the U.S. living in Philadelphia, the capital at the time, he had to actually create a rotating schedule so that his various enslaved servants would be rotated out every six months. Because otherwise he’d just be freeing his servants.

Bouie: Wow. That’s some dedication to slavery from George Washington.

For those slaves who were freed in the North under gradual emancipation or otherwise, what was life like for them, like how did they get along? Because, you know, by the Civil War, there were largish communities of free blacks.

Onion: It’s kind of a darker picture than you might want to hope for.

Emily made clear that they couldn’t get a popular legislative act passed for emancipation. This was kind of a judicial fiat.

And there’s sort of a popular feeling that they didn’t want free blacks hanging around. So they didn’t want them in their cities, and they especially didn’t want to be a fugitive slave magnet. They didn’t want Boston to be perceived as a place where a slave could leave a plantation and sort of emerge into a community where they could take cover. And of course that did happen to some degree, despite their efforts.

She mentioned that in Massachusetts there’d be lists published in the newspaper, of free blacks who were warned out of the city, or warned to be on their best behavior.

Bouie: What’s so interesting about all of this is that you have slaves in some sense fighting for their freedom at cross purposes, with the people, I guess, officially, air quotes, fighting for their freedom.

It’s really striking to me, to see slaves petitioning freedom fighters for their own freedom.

Onion: Yes, and there’s also, if you look at the thousands of people who sort of fled to the English banner, when Lord Dunmore in Britain made a proclamation that if they would come fight for him than they could have freedom—a lot of people took him up on that. You know, Doug Egerton had something interesting to say about that.

Douglas Egerton: Popular culture in movies like Mel Gibson’s The Patriot provide the idea that all Americans—black, white, Native American—were fighting on the same side for the same purpose.

And so, while again the numbers are imprecise, the best data suggest that three-quarters of the Africans and African Americans who picked up a gun during the American Revolution fought for the British side, fought for the side that white Americans regarded as the side of oppression.

And it’s not that Africans or African Americans in South Carolina had any false notions about the British. They understood that the British still were running a slave empire. They were concerned about being resold into the Caribbean islands—Jamaica, Grenada, Barbados—controlled by the British as slave colonies. It simply was that to get their liberty, fighting for the Redcoats was the only option.

So it was certainly true that all Americans, regardless of race, wanted freedom and were fighting for the same cause—they were all fighting for liberty.

But the great irony is that a majority of blacks fought on the Loyalist side, because that was their avenue toward freedom.

And that’s what I think Americans today don’t want to remember. It’s easier to simplify the story—to utterly fictionalize it in movies like The Patriot.

Bouie: You know, I’ve actually thought about that quite a bit recently, just apropos conversations with friends.

We had mentioned earlier the story of Washington leaving Pennsylvania so that his slaves would stay slaves. And the New York Times wrote about that, and some friend and I talked about it. We talked about the irony that you have thousands of slaves fighting for the British, for freedom from an oppression that was far more dire than anything the colonists faced.

What are your thoughts on all of this, Rebecca?

Onion: I mean, it can be incredibly frustrating to look back on what we now perceive as the incredible hypocrisy of this.

And you know, the petition that we read earlier, from the slaves who said, you know, “You call yourselves slaves,” you know, that is almost an offense to someone who actually is in that condition—almost an offense, it’s more than the an offense! And I think it’s good to look at those things and be frustrated, and it’s bad to look at those things and make a movie like The Patriot.

I think a lot of the issue with looking at this history is that it’s just frustrating a lot of the time. There’s just so much hypocrisy and willful irrationality. But I guess the only thing we can do is talk about it.

Bouie: Right. That’s a fact.

The only thing we can do is talk about it and to try to understand it, both on its own terms and in the terms of the people who experienced it. It is not necessarily the case that they saw it as hypocritical. Though, as we saw, many of them were very clear-eyed on the hypocrisy of their fight for freedom while they lived in a place of slavery.

Onion: Yeah.

That seems like a great place to leave off for now.

On the next episode, we’ll be talking about slavery in the early republic.

And we’ll talk about Joseph Fossett, who was one of the Hemingses of Monticello, and was owned by Thomas Jefferson. We’ll be speaking with Annette Gordon-Reed, who wrote an amazing book about the Hemingses of Monticello, and with Heather Andrea Williams, about family separation during slavery and the emotional history of that trauma.

Bouie: And you’ll get to hear me tell at least one awkward story about me being at UVA and hearing people talk about Sally Hemings.