Excerpted from Tyrannicide: Forging an American Law of Slavery in Revolutionary South Carolina and Massachusetts by Emily Blanck. Published by University of Georgia Press.

This article supplements Episode 3 of The History of American Slavery, our inaugural Slate Academy. Please join Slate’s Jamelle Bouie and Rebecca Onion for a different kind of summer school. To learn more and to enroll, visit slate.com/academy.

Undoubtedly, Massachusetts’ inhabitants valued property greatly and tied their own freedom to their ability to freely own, buy, and sell property. Nonetheless, the history of and ideas about slavery in the colony provided a framework wherein individuals could see the humanity in their human property. To begin with, labor relationships in Massachusetts spanned a very broad spectrum of bonded and forced labor. Massachusetts depended on not only slaves but also indentured servants and enslaved Native Americans, who had a slightly different status than black slaves did. This variety provided the people of Massachusetts with a subtler picture of forced labor. And a lack of reliance on slavery paired with an evolving ideology of citizenship in Massachusetts gave slaves enough power to press for their freedom when the right moment arose.1

Despite Massachusetts’ early foray into slavery, an opposition ideology appeared in the first slave law written in the Americas, only two years after African slaves set foot in the colony. This law, appearing in Massachusetts’ first legal code, the 1641 Body of Liberties, was unique in its proscription. Rather than legalizing slavery outright, it outlawed slavery among the Puritans. However, the exceptions of strangers (foreigners who lacked protection from the king) and war prisoners gave an opening to enslave other human beings.

The exception in the case of war prisoners gave the colonists direct permission to enslave Native Americans captured in war. However, the enslavement of Native Americans had a different tenor than the enslavement of Africans. Indian slaves were part of peace negotiations and control of the region.2 They served as collateral with which to negotiate with Native leaders. The indigenous slaves represented an enemy, a conquered people, and a grave threat to their society. African slaves represented a trade transaction, laborers without strings attached.

Conveniently, the slave trade had already begun to spread strangers throughout the Atlantic world. The law, however, also protected slaves, offering them “the Libertyes and Christian usages which the law of God established in Israell.” In the Bible, God instructs Moses not to enslave his fellow Israelites, inviting him instead to enslave “from among the nations around you.” This Massachusetts law establishing slavery demonstrates that its version of the institution drew from a particular moral and religious place. In time, this biblical origin would provide Massachusetts’ slaves with leverage over their masters as ideas of citizenship evolved in the colony.3

The numbers of slaves remained small in Massachusetts, making it easier to keep these strangers under control without a harsh slave code, but most Puritans sought a homogeneous society that made any kind of stranger generally unwelcome. Puritan communitarianism depended on the maintenance of trust among the members of the community. Puritans’ efforts to expunge untrustworthy members with white skin were legendary. Men and women from other cultures with different skin tones posed a more complicated dilemma. Africans embodied a spiritual threat. Tituba, for instance, a West-Indian African, became an important focus during the Salem witch trials. Many Puritan leaders saw her blackness as a sign of the devil. But despite the spiritual threat, Massachusetts reluctantly became a society with slaves, enslaving those Africans that entered its society. During the 17th century, Africans mostly presented Massachusetts with a convenient solution to colonists’ problems with local aggressive Native groups.

As Massachusetts Puritans created a thriving commercial and shipping center, their ships began to partake directly in the Atlantic slave trade, bringing more slaves to their shores. By 1700, the reported number of slaves in the colony was 400. By 1720, it had risen to 2,000 and by 1735, to 2,600. When the colony first took an official count of black slaves in 1754, the census counted 4,489, amounting to 2.3 percent of the total population, and in the next census, in 1764–1765, it reported 5,779, which equaled 2.5 percent of the total population.4

The rapid rise in the number of slaves at the dawn of the 18th century caused Massachusetts leaders to take action. Spiritually, slavery proved an obstacle for the local ministers, as some congregants began to question whether a Christian should own another Christian. In 1693, Cotton Mather took on the challenge of Christianizing the heathen population without ending enslavement. In his 1701 pamphlet The Negro Christianized, Mather assured nervous masters that conversion did not free the slave. He proposed a law that any slave who completed baptism could not be freed just because he or she had received that rite. Mather’s vision of slavery in his pamphlet, consistent with the Hebraic model, idealized the relationship between master and enslaved, representing it as mirroring the father-child relationship in a family. Mather promised that if owners mistreated their slaves, “the Sword of Justice” would sweep through the colony.5

In 1701, Boston, which had the largest slave population in the colony, began passing municipal laws aimed at setting many of the standard limits on slave behavior that other established societies with slaves had set. The laws were not new; they drew on existing laws for controlling other dependents within households: indentured servants and children. They could not drink alcohol, start fires, or assemble. So as not to hamper the slave owners’ profits or property rights, slaves were whipped rather than imprisoned, a punishment that few whites suffered in the early 18th century. Bostonians specified this special punishment in the Act to Prevent Profane Cursing and Swearing and the Act for Preventing All Riotous, Tumultuous and Disorderly Assemblies.6

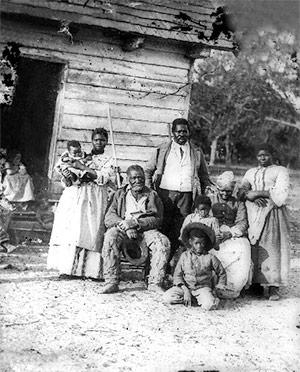

The culture of mastery in Massachusetts persisted throughout the colonial era and seemed to reflect an idealistic vision of slavery. Historian William Piersen calls it “family slavery.” Piersen does not mean to suggest by this term that slaves in Massachusetts received fewer beatings or a lighter workload than slaves elsewhere (indeed, Puritan families beat and worked their own children) but rather that since most slaves there lived within households, the family was a natural model. Such a model did result in slave owners’ feeling a sense of responsibility for the slaves’ well-being, however.7

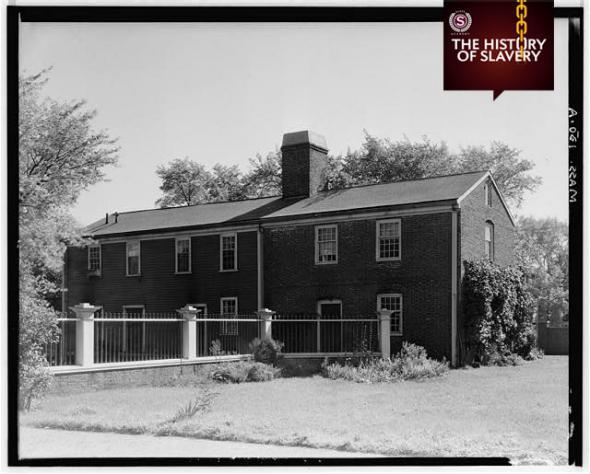

This familial version of slavery meant that the owners intruded on all parts of the slaves’ lives, but white dominance could take on an idealized form that humanized the enslaved person. An example of the ideal master-slave relationship was that between Lucy Terry and her mistress Abigail Wells. Lucy arrived in Bristol, Rhode Island, in 1728 aboard a slave ship. In 1730, when she was probably about 5 years old, Ebenezer Wells purchased her from Samuel Terry of Boston, who had purchased her from Boston slave merchant Hugh Hall.8 Almost immediately, Abigail had her baptized by the Rev. Jonathan Ashley. Wells taught Lucy to read and write.9 Indeed, in many ways, she offered Lucy an unusual degree of support. Although historians might never know why Wells lavished such attention on Lucy, it is possible Wells felt particularly strong affection for her slave because she herself was childless.10

By the time Lucy turned 14, she was entrenched in her work for the Wells family and was familiar with life in the Western Massachusetts town of Deerfield. Her admission to the local church as a full member on August 13, 1744, testified to the completion of her Christianization. Two years later, she used her writing skills to memorialize Deerfield’s resistance to an August 25, 1746, Indian attack in a poem titled “Bars Fight.” Although her poem is today known as the first poem written by a black American, she did not live to see it published in 1855. For 100 years, it seems that only the oral history of Deerfield kept the poem alive.

Extraordinarily, this young woman, born in Africa, had written history for a society that had brought her to America as a slave and that under most circumstances would not have allowed her to read or write. Moreover, her owners successfully raised Lucy in accordance with the ideals of Mather: She seemed to be Christian, obedient, and part of the family and community, and she had mastered English culture.11

With these tools, she was able to pull herself out of slavery. She married a local free black man, Abijah Prince. The two of them worked to purchase her freedom. As a free woman, she continued her remarkable life; she fought for her husband’s land interests before a federal court and appeared in person to appeal her son’s rejection from Williams College.12 However, successful stories of slaves like Lucy did not mirror the uncertain reality of day-to-day life for many slaves. Even supportive owners might lose their temper on occasion. Given the physical closeness of slaves and their masters, it is not surprising that sometimes masters and mistresses committed acts of rash violence against their slaves. For example, using her own arm, the slave Mum Bett of Great Barrington blocked her mistress from striking her sister with a heated fire iron. The event crippled Mum Bett but probably saved the life of her younger sister.13

Moreover, the circumstances of enslavement made it almost impossible for slaves to have their own family lives. Marriage was legal and even encouraged by Massachusetts clergy, but marriage bestowed no rights to the married couple. Men and women frequently lived apart, and a free husband could not impart freedom to his wife, although offspring of free mothers were born free. Like whites, blacks had to abide by the many strict rules of the church if their unions were to be acknowledged. Enslaved women and men posted their intentions at the public meetings and had some of the most distinguished clergy in the colony perform their marriage ceremonies.

Despite this affirmation, married life remained a challenge. The division of slave labor by sex, in particular, made it difficult to maintain a marriage. Whereas men undertook a wide variety of tasks away from the households, women were almost exclusively domestic servants. Even if a married man worked within a master’s household as a house servant, contact with his wife was severely limited. Female slaves, as household servants, worked all hours and slept in the masters’ houses.14 Because New England masters usually owned only one or two slaves, enslaved women or men frequently had to marry partners outside of their homes. As a result, maintaining a marriage for most enslaved men and women meant sustaining a relationship across town or with a partner in a different town. In a sample of enslaved married men and women reported in records of vital statistics of Massachusetts towns, one-quarter of the couples had masters who lived in different towns.15

Having children was also difficult for enslaved women from New England. Not only did the restrictive nature of marriage under slavery reduce contact and hence opportunity for conception, but most masters did little to encourage reproduction. Masters found childbirth inconvenient and actively discouraged it, which contributed to the low birth rate among blacks in Massachusetts. The vital records of Massachusetts towns reveal that during the years when slaveholding was legal, black families had an average of 2.0 children. After the courts abolished slavery in 1783, the average number of children per family shot up to 3.45.16

Despite the failure of most owners to remain faithful to the humanizing, if still abusive, tenets of family slavery, the law recognized many of slaves’ rights as civil beings. After 1670, slaves were no longer strangers under Massachusetts law, which gave them a new status as subjects of the king. Their rank as subjects was not equal to that of white, male property holders, but it was decreed that they deserved protection nonetheless. By the time of the American Revolution, these legal rights provided slaves with unprecedented options in their society. Although no law specifically granted slaves these certain rights, no law restricted the rights of slaves.

1Margaret Newell, “Indian Slavery in Colonial New England,” in Indian Slavery in Colonial America, ed. Alan Gallay (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2009), 43. Christopher Tomlins shows how transitory white indentured servitude was in colonial America. It was a short-lived state for those drawn into it, and it was a short-lived phenomenon in the history of the colonies. The nature of society in the colonies and the need for labor meant that it became challenging to keep white indentured servants; moreover, the supply dwindled in the late 17th century. After then, indentured people in Massachusetts were predominantly white youths, for whom indenture was a stage of life, and Indians, who were driven into a life in and out of indenture by social, legal,and political forces (Freedom Bound: Law, Labor, and Civic Identity in Colonizing English America, 1580–1865 [New York: Cambridge University Press, 2010], 54–56, 255–56).

Timothy H. O’Sullivan/Library of Congress

2Margaret Newell, “The Changing Nature of Indian Slavery,” in Reinterpreting New England Indians and the Colonial Experience, ed. Colin G. Galloway and Neal Salisbury (Boston: Colonial Society of Massachusetts, 2003), 108–9; Newell, “Indian Slavery in Colonial New England,” 37–38; Katherine Hermes, “Jurisdiction in the Colonial Northeast: Algonquian, English and French Governance,” American Journal of Legal History 43.1 (1999): 52–73.

3Compare this to Virginia, for example, which took 40 years to develop laws instituting and regulating slavery.

4U.S. Bureau of the Census, Historical Statistics of the United States, Colonial Times to 1970, 2 vols. (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Commerce Bureau of the Census, 1976), 1:z1- 10; Moore, Notes on the History of Slavery in Massachusetts, 49–51.

5Cotton Mather, Rules for the Society of Negroes, 1693 (Boston: Bartholomew Green, 1714); Cotton Mather, The Negro Christianized (Boston: Bartholomew Green, 1706). Cotton Mather to Reverend Thomas Prince, June 16, 1723, Diary of Cotton Mather, 2 vols. (New York: Fredrick Ungar, 1957), 2:687.

6Ellis Ames, Abner Goodell, and Melville Biglow, eds., The Acts and Resolves, Public and Private of the Province of the Massachusetts Bay, 21 vols. (Boston: Wright and Potter, 1869–1922), 3:318, 997; Records of the Colony of New Plymouth in New England, 12 vols., ed. Nathaniel Shurtleff and David Pulsifer (1855–61; rpt., New York: AMS Press, 1968), 1:21, 29, 47–48, 66, 113.

7William Dillon Piersen, Black Yankees: The Development of an Afro-American Subculture in Eighteenth-Century New England (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1988).

8George Sheldon, History of Deerfield, Massachusetts, 2 vols. (Deerfield, Mass.: Pocumtuck Valley Memorial Association, 1896), 2:898.

9Sharon Carboneti Davis, “Vermont’s Adopted Sons and Daughters,” Vermont History 31.2 (1963): 123; Sheldon, History of Deerfield, Massachusetts, 2:898; Gretchen Holbrook Gerzina, Mr. and Mrs. Prince: How an Extraordinary Eighteenth-Century Family Moved out of Slavery and Into Legend (New York: Amistad Press, 2008) 62.

10Sheldon, History of Deerfield, Massachusetts, 1:359.

11Sheldon, History of Deerfield, Massachusetts, 2:898; 1:540–49, 567; Josiah Gilbert Holland, History of Western Massachusetts, 2 vols. (Springfield, Mass.: Samuel Bowles, 1855), 2:860.

12On the Prince family legal disputes, see Records of the Governor and Council of the State of Vermont, vol. 3 (Montpelier, Vt.: Steam Press of J. and J. M. Poland, 1875) 66–67, “U.S. Circuit Court Docket, 1793–1797,” Records of the United States Circuit Court for the District of Vermont, in Katz / Prince Collection, Schomberg Center for Research in Black Culture, reel 2; Abby Maria Hemenway, ed., Vermont Historical Gazetteer, 5 vols. (Brandon, Vt.: Mrs. Carrie E. H. Pope, 1867–91), 5.3.79. On the Williams College event, see John F. Ohles and Shirley M. Ohles, Private Colleges and Universities, vol. 2 (Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1982), 1407. Biographical information for the Prince family comes from Gerzina, Mr. and Mrs. Prince, 91–107; Sidney Kaplan, The Black Presence in the Era of the American Revolution, 1770–1800 (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Museum Press, 1973), 214–15; Broad Brook Grange No. 151, Official History of Guilford, Vermont, 1678–1961 (Brattleboro: Vermont Printing Company, 1961), 145; Sheldon, History of Deerfield,Massachusetts, 899–900; and David R. Proper, “Lucy Terry Prince: ‘Singer of History,’” Contributions in Black Studies 9–10 (1990–92): 196.

13Catharine M. Sedgwick, “Essay on Mumbet,” Catharine M. Sedgwick I Papers, box 6, folder 6, 2–6 (roll 6, p. 354, on microfilm), MHS, Boston.

14Lorenzo J. Greene, The Negro in Colonial New England (New York: Atheneum, 1968), 110–19.

15William Piersen, Black Yankees, 19. This survey mostly included vital statistics collected from the Massachusetts towns of Arlington, Bedford, Brimfield, Burlington, Chelsea, Dartmouth, Dracut, East Bridgewater, Hamilton, Hopkinton, Lincoln, Manchester, Marblehead, Medford, Medway, and Norton. In these vital statistics records, 125 marriages up to 1850 are recorded. Sixty-four couples included enslaved men or women (Arlington, Mass., Vital Records of Arlington, Massachusetts, to the Year 1850 [Boston: New England Historic Genealogical Society, 1904]; Bedford, Mass., Vital Records of Bedford, Massachusetts, to the Year 1850 [Boston: New England Historic Genealogical Society, 1903]; Brimfield, Mass., Vital Records of Brimfield, Massachusetts, to the Year 1850 [Boston: New England Historic Genealogical Society, 1931]; Burlington, Mass., and Thomas W. Baldwin, Vital Records of Burlington, Massachusetts, to the Year 1850 [Boston: Wright and Potter, 1915]; Chelsea, Mass., and Thomas W. Baldwin, Vital Records of Chelsea, Massachusetts, to the Year 1850 [Boston: Wright and Potter, 1916]; Dartmouth, Mass., Vital Records of Dartmouth, Massachusetts, to the Year 1850 [Boston: New England Historic Genealogical Society, 1929]; Dracut, Mass., Vital Records of Dracut, Massachusetts, to the Year 1850 [Boston: New England Historic Genealogical Society, 1907]; East Bridgewater, Mass., Vital Records of East Bridgewater, Massachusetts, to the Year 1850 [Boston: New England Historic Genealogical Society, 1917]; Hamilton, Mass., Vital Records of Hamilton, Massachusetts, to the End of the Year 1849 [Salem, Mass.: Essex institute, 1908]; Hopkinton, Mass., Vital Records of Hopkinton, Massachusetts, to the Year 1850 [Boston: New England Historic Genealogical Society, 1911); Lincoln, Mass., Vital Records of Lincoln, Massachusetts, to the Year 1850 [Boston: New England Historic Genealogical Society, 1908]; Manchester, Mass., Vital Records of Manchester, Massachusetts, to the End of the Year 1849, Essex Institute, Salem, Mass. Vital Records of the Towns of Massachusetts [Salem, Mass.: Essex Institute, 1903]; Marblehead, Mass. and Joseph Warren Chapman, Vital Records of Marblehead, Massachusetts, to the End of the Year 1849 [Salem, Mass.: Essex Institute, 1903]; Medway, Mass., Vital Records of Medway, Massachusetts, to the Year 1850 [Boston: New England Historic Genealogical Society, 1905]; Norton, Mass., Vital Records of Norton, Massachusetts, to the Year 1850 [Boston: New England Historic Genealogical Society, 1906]).

16Piersen, Black Yankees, 19; Greene, The Negro in Colonial New England, 217.