The Shortening Leash

Six thousand respondents to the Slate survey and the trend is clear: Kids today have a lot less freedom than their parents did.

Photo by Shutterstock

What were you allowed to do when you were a kid? In July, South Carolina mother Debra Harrell was arrested for allowing her 9-year-old daughter to play in the park unattended while she was at work. Harrell’s arrest prompted outrage, but also an outpouring of nostalgia, as indignant readers remembered activities they routinely did as children that are considered near criminal today. So we asked Slate readers to answer a survey about what they were allowed to do as kids, and also what they let their own children do today. About 6,000 of you answered, and the results give a fairly clear picture, over several decades, of a shortening leash for American children.

First, one of our favorite respondent anecdotes, from a reader born in 1977 who wrote of a science experiment gone very, very wrong:

We made napalm in middle school chemistry and were allowed to bring it home. I coated my G.I. Joes in the stuff and lit them on fire in the driveway. Almost burned my hand off grabbing them, but luckily I felt the heat and remembered the napalm's flames were invisible. Parents never found out because they were at work. Latch-key childhood!

We heard a lot about sneaking out, petty theft, amateur arson, drugs, and sexual experimentation from our older respondents. But as time passes, the picture of childhood looks a lot less wild and reckless and a lot more monitored. We asked parents how they would react if they caught their kids doing what they had done as kids. A typical response: “I'd probably freak out and turn my home into a prison.”

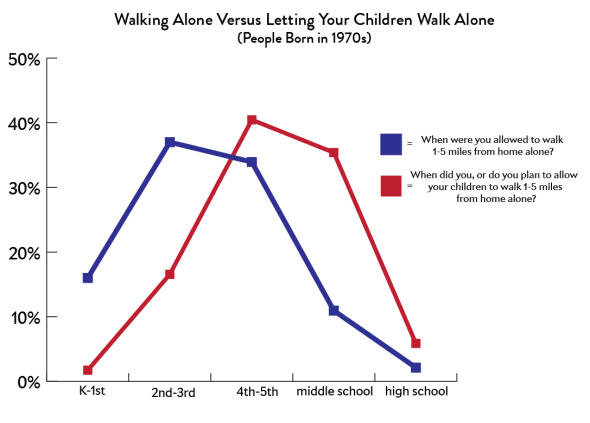

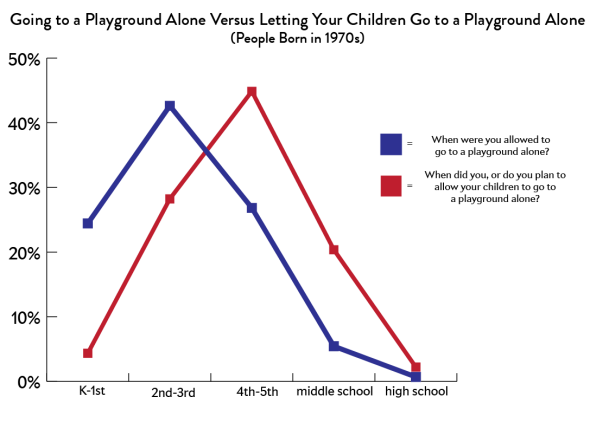

Broad surveys show that childhood norms have shifted drastically over a generation (in 1971, for example, 80 percent of third-graders walked to school alone, but by 1990, only 9 percent did), and our survey of Slate readers confirms that trend. We asked, for example, when readers were allowed to walk 1 to 5 miles from home. For the cohort born in the 1940s, the majority answered second to third grade. By the time we get to the cohort born in the 1980s, the age shifts to fifth grade, and for the 1990s cohort, we are solidly in middle school. A similar trend shows up for a host of other issues, such as going to the playground alone and having to check in with parents when you are out for several hours. The shift in going out after dark is especially dramatic. Earlier cohorts were allowed out at night in middle school, but by the 1990s the norm is solidly high school.

The most noticeable shift in the Slate survey happens between cohorts born in the 1980s and the 1990s, which is consistent with other national surveys. This is because, during the Reagan era, a panic about the dangers of childhood began to take hold. Citizen advocates lamented the perils of playgrounds, and lawsuits forced cities to get rid of what was deemed dangerous equipment. As Paula Fass chronicles in Kidnapped: Child Abduction in America, a few high-profile abduction cases set off a fear of child snatchers lurking on every corner. Ronald Reagan declared National Missing Children’s Day, and milk cartons began featuring missing children’s faces, making every breakfast an opportunity to fear the worst for your children.

Needless to say, the specific fears are overblown. A child is no more likely to be abducted by a stranger today than he was in the 1970s, according to David Finkelhor, director of the Crimes Against Children Research Center. Abductions have increased, but that’s almost entirely due to estranged spouses or parents kidnapping their own children. What has changed over the last 40 years is our sense of community. Mothers work, neighbors talk less, and the divorce rate began to creep upward in the 1970s and has remained at around 45 percent. Rates of single motherhood have exploded since the 1980s. But that kind of change is so ubiquitous that it becomes almost invisible, so instead we turn it into a concrete evil: the creep lurking just around the corner.

Over the years, parental fears have also translated into the view that children are fragile, too tender to handle tricky emotional or physically risky activities, argues Tim Gill, author of No Fear, a critique of our risk-averse society. And we saw this in the Slate survey as well. Cohorts born in the 1970s were allowed to use the stove alone in fourth to fifth grade, and were more at ease with tools. For those born in the 1990s, cooking on the stove and using sharp tools alone didn’t happen until middle school. Earlier generations started to earn money in middle school; the last cohort had to wait until high school.

The outlier trends are also revealing. There is very little change across the decades when kids are allowed to stay home alone. In almost every cohort, it’s between fourth and fifth grade. Apparently, the fears that have gripped American parents since the ’80s pretty specifically center around public spaces—malls, playgrounds, and eventually the Internet. Home, by contrast, remains a safe space (as long as you aren’t using the stove).

One interesting trend that runs in the opposite direction: More middle school–age kids were allowed to go on dates alone in recent years than their predecessors were (you children of the ’70s and ’80s had to wait until high school). Before you assume this has to do with the increased sexualization of kids, remember that teen pregnancies hit a record low this year. The shift may have to do with parents’ more permissive attitude toward sex compared with earlier generations of moms and dads. According to a 2002 AARP study, 20 percent of the parents of boomers thought premarital sex was “not wrong at all” in 1970. Several decades later when boomers became parents themselves, 40 percent believed premarital sex was “not wrong at all.” There’s also the change in the meaning of the word date. Maybe now, going out alone with a romantic interest isn’t all that different from going out with a group of friends. We welcome your theories on this one.

We drilled down on people who were born in the ’70s—the last generation before the Reagan-era panic began—to see what the difference was between what they were allowed to do as kids compared to what they allow their own children to do. The differences were most clear on two measures: When the ’70s children were kids, most of them were allowed to go to the playground alone and walk between 1 and 5 miles alone by second or third grade. When these kids became parents, they were more cautious with their own children, waiting until their kids were in fourth or fifth grade to let them be outside by themselves.

Chart by Ben Blatt

Chart by Ben Blatt

Overall, there is a sense among respondents who grew up in the ’50s, ’60s, and ’70s that they were the last era of children to roam free. “I'm a college professor, and my students often kid me that I must have had a bleak childhood without computers, Smart Phones, and hundreds of TV channels. But I often tell them they were the deprived ones, for, as a Baby Boomer, I had the last golden childhood, where I was free to be a kid,” one woman wrote. Another, born in 1967, wrote, “We did all kinds of things we probably should have gotten in trouble for out in the country. … I'm glad I was raised then and not now. I'm sad my sister, who is 9.5 years younger than me, missed out on the types of experiences and freedom I had growing up.”

Older respondents reported hopping on railway cars, stealing gin from their parents’ liquor cabinet, walking on barely frozen ponds, pouring chocolate milk on cars, and setting a whole roll of toilet paper on fire in the bathroom “just to see what would happen.” They reported a lot of sexual experimentation—sneaking into seedy bars, meeting older men, stealing a credit card to get a subscription to Playboy. One person reported going out with a neighbor boy and stealing a pistol to shoot a chipmunk out of a tree, and added: “PS. He didn’t grow up that well.”

But many respondents also thought their parents should have been keeping a closer eye on them. One, born in 1973 to a working-class suburban family, wrote that she was left home alone at age 4, and that she stole 300 pennies and walked down to a doughnut shop by herself. Another, born in 1965, described her parents as “increasingly detached,” and added, “I'll never forget in high school—my junior year—not seeing my parents in the morning and leaving notes all day long about where I'd be with never a reply. I finally got home around 1 a.m. Yes, it was a school night. They never noticed.”

As Debra Harrell’s experience and our respondents show, there’s a major class wrinkle here. Single parents and poor parents often do not have the resources to keep a close eye on their children, regardless of what era they were born in. One respondent, born in 1980, illustrates this point well:

My mother had three jobs, one as a bar tender, that created a pretty strange schedule. After returning from AM kindergarten while she was sleeping I had a routine of skateboarding, roller skating and then walking around with my stuffed animals around our apartment complex everyday and then going into “neighbors” (I didn't know their name and they hadn't spoken to my Mom) apartments for snacks. I stayed out until I went back to wake her up around 5:00 to pick up my 2 year old brother from daycare and go to work. She did the best she could as a single mother but HOLY SHIT I look back and gasp at how trusting I/she was, and how kind those strangers in a south Denver, one shaky step up from section 8 housing, unit were. I never mentioned anything to her because it seemed normal and even at that age I understood there weren't other options. When you grow up poor you learn from an early age to find the cheapest item on a menu and be grateful for many things those raised in another socio-economic group don't even take for granted; they've never considered it an option NOT to have. “Of COURSE you'd have childcare! Just hire a teenager if you're desperate.” Often times that's even out of reach.

This reader doesn’t totally regret her freedom, however. She lets her second-grader bike alone to a friend’s house, although neighbors complain. Another woman, born in 1960, says she used to hike mountains and explore all day long in the suburbs where she grew up, something she’d never let her own kids do: “I would freak out if my kids had roamed the way I did. But that’s because of the inundation of information we have about dangers to children ie: Child predators, kidnappers, etc,” she writes. A lot of readers expressed that they’d be more upset that their children didn’t feel comfortable sharing their transgressions than they would be about the transgressions themselves. One woman who used to sneak her boyfriend into the house said she doesn’t want her kids to have to do the same things. “I'm trying to cultivate a better relationship with my kids so they don't feel they have to sneak around,” she writes.

Despite the nostalgia, most people, when pressed, don’t want to return to the detached, divorce-boom 1970s era of parenting. But they also feel a little ambivalent about how hovering they’ve become. As one woman, born in 1972, puts it, “Sadly, I find myself parenting from a newspaper headline point of view. If something bad happened after a parenting choice I made, how would it sound when reported in the papers? It makes me more conservative than I'd like to be and my kids miss out on the independence of open-ended play, like I had.”

Maybe a happy medium would be relishing the closer ties between parents and children now, but also recognizing that part of being a good, caring parent is letting children discover things on their own. What’s the harm of setting a roll of toilet paper on fire? After all, there is a sink in the bathroom.

If you wrote us about your childhood experiences in the survey and wouldn’t mind being contacted, please send an email to doublexgabfest@slate.com. Put “survey” in the subject line and a sentence in the email about what you wrote so we can match you up to your survey answer. Thank you!