Gone to the Dogs

The strange rituals—and stranger people—you find at the dog park.

Still via Slate Video

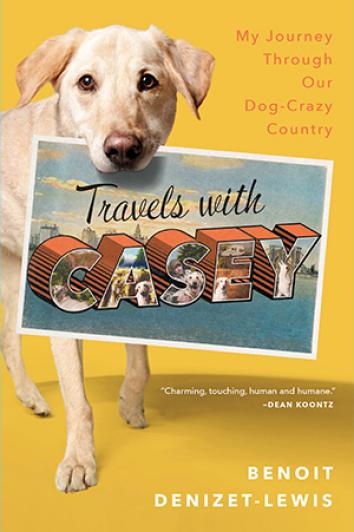

This article is adapted from Travels With Casey: My Journey Through Our Dog-Crazy Country.

My dog is not a morning person, so he didn’t immediately react when I tried to wake him up at 5:35 on a cold, gray Manhattan day. Normally the word “walk” elicits all manner of canine gesticulation (spinning, jumping, barking), but at that hour it elicited a strange and suspicious stare. “Now?” he seemed to be thinking.

I’d decided to spend a full day at the Tompkins Square Dog Run in the East Village. I was researching a book about dogs in America, for which I would soon be driving around the country with my dog, Casey, and meeting dog-obsessed Americans—including dog-wielding hitchhikers, K-9 cops, pet psychics, gay cowboys, and “Dog Whisperer” Cesar Millan.

I knew that if I wanted to understand the place of dogs in contemporary America, I had to spend some time in dog parks, where everyone knows your dog’s name—and some even know yours. Dog parks are a relatively modern invention, a “kind of victory over the anonymity and transience of life,” as writer Mary Battiata put it. They’re a place of long-lasting friendships, longer-lasting feuds, and dog-park know-it-alls who disapprove of the job you’re doing with your pet. At a dog park in Boston, where I live, the park’s queen bee once asked me what I was feeding Casey.

She didn’t like my answer. “Well, you can certainly feed him that if you want to kill him,” she barked.

I’d come to New York City to experience the rituals and rhythms of the city’s oldest dog run. The New York Times has described Tompkins Square (also called First Run) as a lively and contentious place, one brimming with dog-park politics and the kind of class-related tension that led one woman to declare that some dogs deserved to get “roughed up because they wore sweaters.” Maybe I’d get lucky and see a brawl. Even if I didn’t, Casey would get a full day of chasing tennis balls and humping dogs.

We got to the run a few minutes after 6 a.m. (when it officially opens), but the gates were locked. Casey sniffed a fire hydrant while I tried to figure out what to do. A few seconds later, I spotted a woman and her large dog slipping through a hole in the park’s fence. “We’re in!” I told Casey, who pranced along next to me, suddenly game for this early-morning adventure.

The woman was the only person in the run when we arrived. She sat on a bench in the section for large dogs, which was separated from the little-dog area by a gigantic wooden dog bone sculpture attached to a 3-foot-high fence. The woman’s name was Robyn, she told me, and her dog’s name was Charlie. A big, friendly black and gray Siberian husky, he’d been a gift from her ex-husband.

“We’d separated after 30 years together,” she explained, “and he gave Charlie to me hoping that I would get back with him. Basically, he tried to bribe me with a dog!”

“Did it work?” I asked.

“Well, yes and no. I didn’t take him back at first. But, four years later, we did get back together.”

“You made him sweat it out.”

“Well, you know ... ” she said with a guilty smile. “Once I had Charlie, I didn’t even really feel like I needed a husband. You know what I mean? Dogs can be a lot more fun than husbands. And Charlie is the most amazing gift in my life. Dogs are the most amazing gift!”

A few minutes later, a man arrived with two dogs in tow. “He’s a dog walker and has been coming here longer than just about anybody else,” Robyn explained as she introduced us. (He asked that I not use his name, so I’ll refer to him here only as “The Man.”)

“Yeah, I have no real life to speak of,” The Man told me, eyeing me with suspicion. “But enough about me. Who the hell are you?”

“This guy’s writing a book about dogs,” Robyn explained. “He’s spending all day at the run.”

“All day at the run?” The Man guffawed. “Dude, you’re nuts. And your poor dog! He’s going to hate you by the end of the day.”

We heard the clacking of the gate at the entrance to the run, where a woman in her early 40s entered with her retriever mix, a cup of coffee, and that morning’s New York Times.

“This dude’s writing a book,” The Man told her as she plopped down next to me.

“Congratulations,” she said.

“No, about this dog run,” he clarified.

“Oh, well, there are plenty of crazies here. You’ll have lots to write about.”

The Man laughed. “There’s this saying—to own a dog in Manhattan, you have to be crazy,” he told me.

“Or rich,” the woman said. She looked at me, then Casey. “Is this your yellow Lab?”

Casey stuck his nose in her lap, and she fawned over him for a few seconds before her dog started humping him. “He likes Casey!” The Man said. As if on cue, Casey starting humping Charlie.

I asked the morning group if any celebrities were regulars at the run. The Man proudly ticked off a dozen names, including Molly Ringwald, Parker Posey, and Josh Lucas. The woman rolled her eyes. “You’re such a star-fucker,” she said.

“There’s a lot more,” he went on, undeterred. “Elijah Wood comes here sometimes. You know, the hobbit. He has a girlfriend who lives nearby and who has three small dogs. A dog park is really a great place to meet people. We’ve actually had a few marriages happen between people who first met each other here.”

“I try not to date where my dog shits,” the woman countered, shaking her head.

The conversation turned to her love life. “I’ve been single for so long,” she lamented. “If you’re a woman and you’re reasonably successful in your career, you’re fucked. Men are intimidated by it.”

“Any new prospects?” The Man wanted to know.

“Actually, yeah. I have a live one.”

“A V-8, or a V-6?”

“Well, he’s a former Marine, so I would imagine he’s a V-8,” she said. “One can hope.”

The Man turned his attention to me. “So, Benoit, what’s your type? You straight, bi, gay?”

I laughed. “Is this pretty typical? You ask newcomers what they’re into?”

The woman patted my leg. “Of course! You’re totally fresh meat.”

Later, she explained that she used to live uptown and was a regular at the dog run in Madison Square Park, which she recalled as considerably less crazy than this one. “Down here, there’s so much drama,” she said. “The only time I can tolerate this place is early in the morning. The lunatics come out later.”

“So you guys don’t consider yourselves lunatics?” I asked with a smile.

“There’s normal New York crazy, which is what we are,” she explained. “Then there’s batshit New York crazy, the people who have nothing better to do than start drama in the dog park. And don’t even get me started on the people on the little-dog side. They’re an entirely different kind of crazy.”

“They’re mostly just pretentious,” The Man said. “People with big dogs tend to be laid-back. People with small dogs are like, ‘Don’t hurt my pee-pee!’ ”

Still via Slate Video

* * *

Later that morning, the cutest puppy I’d ever seen—a 4-month-old golden retriever named Bean who looked like the dog from the Snuggies television commercials—bounded into the First Run. There were about 15 people there when Bean arrived, and for a good five minutes nearly everyone stopped what they were doing to take turns petting her.

“Having a cute dog in New York City makes living here so much cooler,” Bean’s owner, a friendly photographer in his 30s, told me. “I’ll be walking her down the street, and people will just grin when they see her. People stop and pet her and talk to me. The biggest, meanest-looking guys are like, ‘Oh, it’s a PUPPY!’ ”

While Bean played with a stick, I meandered over to a young dog walker named Ryan. He was at the run with two dogs, including a friendly pit bull named Bullet. A regular here, Ryan told me he came to Tompkins Square Park three times each day with a total of 10 dogs. He likes holding in-depth conversations with his charges. He calls them “knuckleheads,” asks them how they’re doing, and philosophizes about their inner thoughts. “I wonder what they’re thinking, man,” he said. “Wouldn’t be it be great if there was some real deep shit going on in their heads?”

Growing up, Ryan never thought he’d walk dogs for a living. In fact, he stumbled into the job after several years of bartending and an unsuccessful one-day stint as an office temp. “My boss at the office was like, ‘Wow, you really suck at this,’ ” Ryan recalled. “But he had a friend who was looking to hire another dog walker for his dog walking company. So he put me in touch, and I started my dog walking career the next day. First job I’ve ever had with health insurance!”

Though he loves dogs, Ryan doesn’t have one of his own. “I spend all day out walking dogs,” he explained, “so if I had one at home, I’d have to hire a dog walker for him. That just seems silly. I have two cats. No need to hire a cat walker.”

When Ryan left the run, I spent some time throwing a tennis ball for Casey. Then I noticed a pale, dark-haired young woman sitting on a bench near the run’s entrance. She sat staring straight ahead, her small hands folded in her lap. Though her eyes were open, she appeared to be meditating.

“How are you doing?” I asked, joining her on the bench.

“I just got out of a mental hospital, actually,” she said. I didn’t know what to say to that. I scanned the dog park for a hidden camera while the woman’s dog sniffed Casey’s rear end.

“I’ve had really severe OCD for four years,” she continued. “I’m an actress, and it’s been so bad I haven’t been able to work for the last year. But I’m much better now that I’m off my medications. I had a sort of intuitive dream that God told me to get off the medicine. It was all making me feel even more bonkers.”

She was interrupted by a helicopter flying over the park. Several dogs stopped what they were doing and looked up in the sky toward the loud, strange noise.

“Since I’ve been out of the hospital,” she went on to say when the chopper was gone, “I try to come to the run as often as I can. It helps me get back to my center, and it’s one of the highlights of my day. I missed my dog so much in the hospital. I just have to wink at her, and she knows what I want to do. She’s very in tune with me. Very in tune! When I was on a plane and having seizures because I was in withdrawal from my medicines, she started having seizures, too. It’s like she was feeling everything I was feeling.”

She continued like this for a few minutes, stopping occasionally for air. Then she abruptly changed the subject. “Do you have a girlfriend?” she wanted to know.

“I’m gay, actually,” I replied. I could imagine a guy offering her a similar answer even if he wasn’t gay, but in my case it happened to be true.

She cocked her head slightly to the side and squinted her eyes. “Really? You don’t seem gay. You don’t have that voice.”

“We come in many voices,” I assured her.

“I’m not sure that’s true,” she said.

A minute later The Man entered the run with two new dogs. He seemed happy to see me. When I was within shouting distance, he smiled broadly and yelled, “Dude! I have good news, and I have bad news!”

I asked for the good news first. “I looked you up when I got home,” he said. “You checked out—you’re apparently a real writer.”

“And the bad news?”

“Your last book’s available on Amazon for 1 cent,” he said with a chuckle. “Hopefully this one will fare better.”

* * *

It’s worth pausing here, I think, to tell the story of how First Run came to be. The best source for its colorful history is Michael Brandow’s book New York’s Poop Scoop Law: Dogs, the Dirt, and Due Process, which is far more interesting than its title suggests and tells the fascinating story of how dogs came to be one of the city’s most contentious political issues.

Back in the 1970s, before picking up after your pooch was an expectation of canine ownership, the city’s sidewalks and parks had been littered with dog doo. In a 1975 letter to the New York Times, a grumpy New Yorker had lamented the sad, soiled state of Central Park: “It has become a dumping ground for defecating dogs. ... The crisp green grass, the smell of blossoming cherry trees, the playing fields are all being taken from us by the hordes of dogs that romp freely. ... Can nothing be done? Are we all to be slaves to people who find pleasure in keeping Great Danes in three-room apartments?”

But when New York City Mayor Ed Koch proposed the country’s first poop-scoop law in 1978, dog owners were aghast—and promised to revolt. “Like the Jews of Nazi Germany,” the head of New York’s Dog Owners Guild at the time complained, “we citizens, including the old and infirm, are being humiliated by being forced to pick up excrement from the gutter.”

Photo by David Shankbone/Creative Commons

Many dog owners saw the proposed law as impractical (Koch made clear that dog owners were not to dispose of poop in public waste receptacles), and as a slippery slope, with the ultimate goal being the eradication of dogs from Manhattan. Their paranoia wasn’t entirely misplaced. Dog bashing at the time was a favorite pastime of many New Yorkers, best expressed by writer Fran Lebowitz in perhaps the greatest takedown of dogs ever published.

“Pets should be disallowed by law,” she wrote in 1981. “Especially dogs. Especially in New York City. I have not infrequently verbalized this sentiment in what now passes for polite society, and have invariably been the recipient of the information that even if dogs should be withheld from the frivolous, there would still be the blind and the pathologically lonely to think of. I am not totally devoid of compassion, and after much thought I believe that I have hit upon the perfect solution to this problem—let the lonely lead the blind.”

But dog issues weren’t just dividing New York. As dog ownership exploded across the country in the 1970s, the National League of Cities listed dog and other animal concerns as the primary issue about which local public officials received complaints. In Berkeley, California, the country’s first dog park opened in 1979 but didn’t become official until after several years of squabbling, lobbying, and a “paw-tition” signed by local dogs (presumably representing their owners).

In New York City, dog runs and parks had been proposed as early as the 1960s as a solution to “both the grass shortage and the poop surplus,” as Brandow put it. (One landlord even built a rooftop dog run on his building and suggested that other landlords do the same.) But the idea that anyone should provide extra accommodations for dogs or their owners struck some as preposterous. Many New Yorkers, Brandow wrote, “were not about to hand over parcels of public land, however minuscule, permanently to those filthy, marauding beasts that had, in their opinions, plagued the city.” People worried that the runs would be breeding grounds of filth and disease and would inevitably pollute surrounding areas. Underlying much of their anger was a belief that if a person wanted a dog that badly, he or she should live somewhere with a yard. Even some dog owners disliked the idea of dog runs, which they saw as a kind of forced segregation. Others worried about whether their dogs would be safe there.

“Critics imagined horrible scenes of loose predators, the large animals consuming the smaller ones in a single bite,” according to Brandow. But though there is an occasional dogfight today in New York City’s dog runs, one could argue that dogs get along better there than their human counterparts. The Tompkins Square Dog Run, in particular, is known for its discord. In the last decade, park regulars have clashed over changing the run’s surface from wood chips to a sandy, crushed-rock substance; they’ve argued about whether small dogs should get their own section; and they’ve armed themselves with knives in response to several pit bull attacks in the run. In 2003 the New York Times summarized the park’s travails under the headline “Straining at the Leash.”

During my day at First Run, I heard stories of people leaving the park in a huff, never to return. Some of those who didn’t leave had settled into warring factions, ignoring each other or glaring at each other from across the park.

“I’m from a small town in Texas, so I’m used to dealing with idiots and bullies,” a man in his mid-30s told me. We were sitting on a bench later that afternoon while our dogs played. “But what I’ve seen in here is really beyond the pale. A lot of these people are nice until you piss them off, and then they will get personal and try to upend your life.”

“What kinds of things do they say?” I asked.

“Some people said I’d been to jail,” he said, shaking his head. “It’s out of control. This run has a lot of bitter people. And I’m probably one of them. It’s funny to see all the dogs of rivals playing together. We’ll just kind of shoot dirty looks to each other from across the park while our dogs have fun. People will mutter under their breath, ‘Anna, get away from him!’ but the dogs don’t know any better.”

He turned to face a friend of his, a young woman who sat cross-legged next to us. “Did [The Man] and company ever warn you about me, or did they just give you dirty looks when you talked to me?” he asked the woman.

“Just a few looks,” she replied, seeming bored by the conversation.

He turned back toward me. “They’re definitely not happy we’re talking,” he said, referring to The Man and the run’s elected manager, Garrett, who were huddled together on the other side of the park.

When I approached Garrett later that afternoon, he initially said he wasn’t in the mood to talk dog-park drama—his 12-year-old Rhodesian Ridgeback had died a few days earlier. “I’m here physically, but I’m not really here,” he told me. “I’m still in a daze.”

Eventually, though, Garrett opened up. “Dog parks are a lot like post-apocalyptic culture,” he said as we sat on a picnic table. It was midafternoon, a slow time at the park. Casey was exhausted; he’d just finished a round of humping and was now sprawled out on the ground next to our table. “We’re all in this little piece of land, having a weird kind of power struggle and attempting to get along,” Garrett continued. “You’re forced to interact with people you normally wouldn’t.”

“Do you think people sometimes forget about everything that’s good about this kind of park?” I asked Garrett. “It seems like I’ve heard a lot of complaining today, and not a lot of appreciation. All day, I’ve seen people walking by and stopping just to watch the dogs play. It seems like First Run is so important to this community, whether you have dogs or not.”

“It is,” Garrett said. “Even with all the drama, people come here because it’s a community; it’s home. When 9/11 happened, everyone came rushing to the dog park. People felt lost, and we all wanted to be with others who would understand. And in this city where people don’t always feel connected, where so many people pay $2,500 a month to live in a shoebox, it’s telling that so many of us rushed straight to the run. It was the natural place to come.”

* * *

Though I’d intended to stay at First Run late into the night, by 5 p.m. I was hungry, tired, and desperate for a change of scenery. Before leaving, though, I left Casey in the big-dog section and walked over to hang out with the little dogs.

Earlier in the day, I’d watched a Boston terrier put a tiny, fluffy white dog into what appeared to be a headlock. “Brutus, no headlocks!” screamed the dog’s owner, a man in a New York Jets cap.

At this hour, though, it was quiet. I struck up a conversation with three women in their 20s and told them all about the trouble over on the big-dog side.

“We have our drama here, too,” one assured me, “but we’re way more passive-aggressive about it.”

“We have our crazies,” another agreed. “One woman wanted her dog to give birth in the run. We were like, ‘Um, no, they have vets for that!’ ”

I looked back at Casey, who stared sadly at me through the fence.

“You can totally bring him in here if you want,” one of the young women told me.

“The people who would start drama about it aren’t here right now.”

“I actually need to get out of here,” I said. “I’ve been at the run since 6 this morning.”

On my way out of First Run with Casey, I bumped into The Man, who was walking back into the park with more dogs.

“You’re leaving?” he asked. He seemed sad.

“I have to get out of here,” I insisted.

“You got a problem with this place?”

“It’s a bastion of free love and good will, to be sure,” I told him with a smile.

He laughed and triumphantly raised his arms toward the sky. “Hey, man. If you can survive a dog park in New York City, you can survive anywhere!”

This article is adapted from Travels With Casey: My Journey Through Our Dog-Crazy Country by Benoit Denizet-Lewis. Copyright © 2014 by Benoit Denizet-Lewis. Printed by permission of Simon & Schuster Inc. To learn more about the book, visit www.travelswithcasey.com.

Boston terrier photo by Jean-Pierre Dagneaux.