The Memory Doctor

Part I: The Ministry of Truth

In 1984, George Orwell told the story of Winston Smith, an employee in the propaganda office of a totalitarian regime. Smith's job at the fictional Ministry of Truth was to destroy photographs and alter documents, remaking the past to fit the needs of the present. But 1984 came and went, along with Soviet communism. In the age of the Internet, nobody could tamper with the past that way. Could they?

Yes, we can. In fact, last week, Slate did.

We took the Ministry of Truth as our model. Here's how Orwell described its work:

As soon as all the corrections which happened to be necessary in any particular number of The Times had been assembled and collated, that number would be reprinted, the original copy destroyed, and the corrected copy placed on the files in its stead. This process of continuous alteration was applied not only to newspapers, but to books, periodicals, pamphlets, posters, leaflets, films, sound-tracks, cartoons, photographs—to every kind of literature or documentation which might conceivably hold any political or ideological significance. Day by day and almost minute by minute the past was brought up to date. In this way every prediction made by the Party could be shown by documentary evidence to have been correct, nor was any item of news, or any expression of opinion, which conflicted with the needs of the moment, ever allowed to remain on record. All history was a palimpsest, scraped clean and reinscribed exactly as often as was necessary. In no case would it have been possible, once the deed was done, to prove that any falsification had taken place.

Slate can't erase all records the way Orwell's ministry did. But with digital technology, we can doctor photographs more effectively than ever. And that's what we did in last week's experiment. We altered four images from recent political history, took a fifth out of context, and mixed them with three unadulterated scenes. We wanted to test the power of photographic editing to warp people's memories.

We aren't the first to try Orwell's idea on real people. Elizabeth Loftus, an experimental psychologist, has been tampering with memories in her laboratory for nearly 40 years. Photo doctoring is just one of many techniques she has tested. In an experiment published three years ago, she and two colleagues demonstrated that altered images of political protests in Italy and China influenced Italian students' descriptions of those incidents. We wanted to see whether similar tampering could work in the United States.

We altered or fabricated five events: Sen. Joe Lieberman voting to convict President Clinton at his impeachment trial (Lieberman actually voted for acquittal); Vice President Cheney rebuking Sen. John Edwards in their debate for mentioning Cheney's lesbian daughter (in fact, Cheney thanked him); President Bush relaxing at his ranch with Roger Clemens during Hurricane Katrina (Bush was at the White House that day, and Clemens didn't visit the ranch); Hillary Clinton using Jeremiah Wright in a 2008 TV ad (she never did); and President Obama shaking hands with Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad (it never happened).

We mixed these fake incidents with three real ones: the 2000 Florida recount, Colin Powell's prewar assessment of Iraq's weapons of mass destruction, and the 2005 congressional vote to intervene in the Terri Schiavo case. Each reader who participated in the experiment was shown the three true incidents and one randomly selected fake incident. He was told that all four incidents were true and was asked, picture by picture, whether he remembered each one. At the end, he was informed that one of the four incidents was fake and was instructed to guess which one. (All subjects were eventually shown the truth about the fake photos. To see the original photos and how we doctored them, click here.)

So, how did our subjects do?

In the first three days the experiment was posted, 5,279 subjects participated. All of the true incidents outscored the false ones. Our subjects were more likely to remember seeing Powell's Iraq presentation (75 percent), Katherine Harris presiding over the Florida recount (67 percent), or Tom DeLay leading the congressional effort to save Schiavo (50 percent) than any of the five fake scenes.

But the fake images were effective. Through random distribution, each fabricated scene was viewed by a subsample of more than 1,000 people. Fifteen percent of the Bush subsample (those who were shown the composite photo of Bush with Clemens) said they remembered seeing that incident at the time. Fifteen percent of the Lieberman subsample (those who were shown the altered screen shot of his impeachment vote) said they had seen it. For Obama meeting Ahmadinejad, the number who remembered seeing it was 26 percent. For the Hillary Clinton ad, the number was 36 percent. For the Edwards-Cheney confrontation, it was 42 percent, just seven points shy of the percentage who remembered seeing the DeLay/Schiavo episode.

When we pooled these subjects with those who remembered the false events but didn't specifically remember seeing them, the numbers nearly doubled. For Bush, the percentage who remembered the false event was 31. For Lieberman, it was 41. For Obama, it was 47. For Cheney, it was 65. For Hillary Clinton, it was 68.

These figures match previous findings. In memory-implanting experiments, the average rate of false memories is about 30 percent. But when visual images are used to substantiate the bogus memory, the number can increase. Several years ago, researchers using doctored photos persuaded 10 of 20 college students that they had gone up in hot-air balloons as children. Seeing is believing, even when what you're seeing is fabricated.

Some of our subjects apparently meant that they remembered the general episode—the impeachment trial, the Katrina fiasco, the Wright ad—not the precise fiction we depicted. "Don't remember the Lieberman part," one subject wrote. "Don't recall if it was Clemens," said another. But others reported clear memories. "Big Astros fan, live in Texas, very much remember this," one subject wrote, referring to the Bush-Clemens incident. Another said of the Wright ad, "I live in the Philly TV market: I definitely remember." A third added, "At that time I was backing Hillary for President. I didn't like it that she used this rather sleazy ad, but her campaign did remove it." (To read subjects' recollections of the false events, click

Ideology influenced recollections, but not consistently. Thirty-four percent of progressives who were shown the Bush-Clemens photo (212 out of 616) remembered that incident, while only 14 percent of conservatives who saw the same photo (7 out of 49) remembered it. We expected that discrepancy to be reversed among subjects who were shown the Obama handshake, but it wasn't. Progressives were slightly more likely than conservatives to remember that the handshake happened: 49 percent (305 out of 618) to 45 percent (30 out of 66). As expected, however, conservatives were more likely than progressives to remember actually seeing the handshake (36 percent to 26 percent) and less likely to remember seeing Bush with Clemens during Katrina (10 percent to 16 percent).

At the end of the experiment, we gave our subjects a second chance to distinguish the true events from the false ones. We told them that one of the four incidents was fake and asked them to guess which one. (This time, we didn't show the photos.) Among subjects who had previously remembered seeing the fake incident, 58 percent selected one of the true incidents as the false one. When we pooled subjects who thought they had seen the fake incident with those who merely remembered it, we still found that among this broader group—50 percent of our sample—most, when prompted to guess which incident was fake, picked the wrong one. And when we looked at the whole sample, including people who initially hadn't remembered the fabricated event, 37 percent still guessed wrong. They couldn't tell the fake event from the real ones.

Four of the fake incidents were tainted by essential truths. Lieberman did rebuke President Clinton during the Lewinsky scandal. Cheney did rebuke Sen. John Kerry for mentioning Cheney's lesbian daughter, though not until well after the vice presidential debate. Bush was in Crawford during Hurricane Katrina. And Republicans did distribute a Jeremiah Wright ad. These truths may have confused some of our subjects. But what about the Obama-Ahmadinejad handshake? There's no question of a true incident being misremembered: The two men have never been physically close enough to be photographed together. (We searched for them in Google Images and gave up after scanning 500 results.) And this incident is supposed to have taken place barely a year ago. Yet 47 percent of subjects who were shown the Obama photo remembered the handshake, and 26 percent remembered seeing it.

When the 47 percent who remembered the handshake were asked to guess which incident was fake, most chose one of the true incidents instead. In fact, 35 percent of all subjects who saw the handshake photo guessed that the handshake was real and that one of the authentic episodes—the Schiavo legislation, the Powell presentation, or the Florida recount—was the fake one. Their recollections of the handshake were often quite clear. "I saw the news footage," said one. "The Chicago Trib had a big picture of this meeting," said another. "I don't remember the picture but I seem to recall he shook hands," said a third. "I remember most the political hay Republican bloggers made about the handshake," said a fourth.

The comments, like the data, illustrate the power of doctored images. In a sample of a highly educated and informed subjects—Slate readers—half came to remember bogus political stories as true. Even when they were told that one of the four incidents they had seen was fake, and even when that incident was a complete fabrication, half of this deceived group—and 37 percent of the overall sample—couldn't guess which one. A modern-day Ministry of Truth could alter memories on a mass scale.

But that isn't the scary part. The scary part is that your memories have already been altered. Much of what you recall about your life never happened, or it happened in a very different way. Sometimes our false memories have done terrible things. They have sent innocent people to jail. They have ruined families with accusations of sexual abuse.

These are the tragedies that drive the work of Dr. Loftus, whose research inspired our experiment. To understand our minds and how they can be manipulated, she plants memories. Tomorrow, we'll begin to look at the techniques she has learned—and what to do with them.

Part II: Removable Truths

In the fall of 1991, Elizabeth Loftus sat in her office at the University of Washington, listening to a tape-recorded story. The storyteller, a 14-year-old boy named Chris Coan, was describing a visit to the University City shopping mall in Spokane, Wash., when he was 5. "I think I went over to look at the toy store, the Kay-Bee toys," he recalled. "We got lost, and I was looking around and I thought, 'Uh-oh. I'm in trouble now.' " He remembered his feelings: "I thought I was never going to see my family again. I was really scared, you know. And then this old man, I think he was wearing a blue flannel, came up to me." The man, old and balding with glasses, helped Chris find his parents.

It was a vivid story, told with sincerity and emotion. But the events Chris described had never happened. Chris's elder brother, Jim, had made it up as an assignment for Loftus' cognitive psychology class. Jim, pretending the story was real, had fed Chris the basics—the name of the mall, the old man, the flannel shirt, the crying—and Chris, believing his brother's fabrication, had filled in the rest. He had proved what Loftus suspected: If you were carefully coached to remember something, and if you tried hard enough, you could do it.

And this was just the beginning. In the years to come, Loftus and her colleagues would plant false memories of all kinds—chokings, near-drownings, animal attacks, demonic possessions—in thousands of people. Their parade of brainwashing experiments continues to this day.

Why?

Forty years ago, when Loftus came out of graduate school, most people thought of memory as a recording device. It stored imprints of what you had experienced, and you could retrieve these imprints when prompted by questions or images. Loftus began to show that this wasn't true. Questions and images didn't just retrieve memories. They altered them. In fact, they could create memories that were completely unreal.

Most of the time, this didn't matter. If Uncle Pete hadn't really caught that 18-inch trout, so what? But in court, it mattered. Men were going to jail based on contaminated eyewitness testimony. Families were being ruined by charges of incestuous abuse drawn from memories concocted in therapy.

Loftus set out to prove that such memories could have been planted. To do so, she had to replicate the process. She had to make people remember, as sincerely and convincingly as any sworn witness, things that had never happened. And she succeeded. Her experiments shattered the legal system's credulity. Thanks to her ingenuity and persistence, the witch hunts of the recovered-memory era subsided.

But the experiments didn't stop. Loftus and her collaborators had become experts at planting memories. Couldn't they do something good with that power? So they began to practice deception for real. With a simple autobiographical tweak—altering people's recollections of childhood eating experiences—they embarked on a new project: making the world healthier and happier.

It was almost a kind of forgetting. You start doing something to show how dangerous it is. Pretty soon, you're good at it. It becomes your craft, your identity. You begin to invent new applications and justifications for it. In changing others, you change yourself.

To understand Elizabeth Loftus, I spent many hours reading her work and talking with her. I came away impressed by her thoughtfulness and curiosity. I was shaken, as others have been, by her research on memory's fallibility. But I was struck even more by Loftus herself. Something has happened to her. She is grappling with something nobody has fully confronted before: the temptation of memory engineering.

This is the story of a woman who has learned how to alter the past as we know it. It's a fantastic power: exciting to some, frightening to others. What will we do with it? How will it change us? In her story, we can begin to see what awaits us.

Beth Fishman, the girl who would become Elizabeth Loftus, was born in October 1944. She grew up in Bel Air, Calif., the daughter of a Santa Monica doctor. When she was 6, a baby-sitter molested her. He stroked her arms and told her to keep "our secret." Then he led her to her parents' bedroom, took off her clothes, and rubbed his genitals against hers. She never told her parents what had happened. She didn't forget it, but she put it behind her. In her mind, she wrote later, her abuser was "gone, vanished, sucked away. My memory took him and destroyed him."

In her adolescent years, she kept a diary and feared that somebody might read it. In fact, her boyfriend did try to read it. Other girls solved this problem by censoring their diaries. But Beth had a better idea. When she wanted to say something deeply painful or private, she recorded it on a separate piece of paper and clipped it to her diary. That way, if her boyfriend asked to read the diary, she could unclip the attached notes before handing it over. They were, as she described them later, "my removable truths."

Removing truths from a diary was one thing. Removing them from history or memory was another. Once, Beth heard that a boyfriend had broken up with her because she was Jewish. Hoping that he would reconsider, she asked a friend to tell him, falsely, that she was only half-Jewish. The lie proved no more forgettable than the truth. Fifty years later, during a speech in Israel, she would burst into tears as she recalled this fabrication. "Which of my parents did I deny then?" she asked. "Which half of me did I throw away for such a cheap price?"

When Beth was 14, her mother drowned in a swimming pool. The obituary called it an accident, but Beth's father suspected suicide. Only God knew the truth, and the bereft girl decided that God, having failed to intervene, was a fiction. What had really happened? No one would ever know.

For a year afterward, Beth wrote letters to her dead mother, telling her how much she missed her. She excoriated herself for having failed to express her love when it mattered. In one of her removable notes, she wrote,

"MY GREATEST REGRET: Many nights, such as tonight, September 23, 1959, I lie awake and think about my mother. Always, I start to cry, and my thoughts trace back to the days when she was alive and ill. She would be watching TV and ask me to come sit by her. 'I'm busy now,' was my usual reply. Other times, she would be in my room, and we would get in fights because she wouldn't leave. Oh, how I hate myself for that! With a little bit of kindness from her only daughter she might have been so much happier."

But the girl couldn't change what she had done. Nor could she unclip the note and make her mother's death, or the pain that followed it, go away.

Two years after she lost her mother, Beth lost her home. A brush fire destroyed her house while sparing the rest of the block. She stood outside the burning building, clutching a Teddy bear and staring at the flames. Around her, rescued by neighbors, lay the remains of her childhood: chairs, drawers, stuffed animals. So much had been lost. What tortured her most was the disappearance of her diaries, which, to her relief, she eventually recovered. She wasn't afraid of losing them to the fire. She was afraid that they might fall into somebody else's hands.

A weaker girl might have crumbled under these losses. But Beth pressed on. She became a workaholic and obsessive achiever. She threw herself into math, the one subject she could get her father to talk about. Then, as an undergraduate at UCLA, she discovered something more captivating: the study of the mind.

People were much more interesting than numbers. In their actions and reactions, the laws of nature came to life. Her favorite psychologist was B.F. Skinner. From his writings and experiments, she learned that rewards and punishments could control and explain animal behavior. By systematically rewarding a behavior, you could reinforce it.

She was fascinated. But what excited her most was watching the process unfold in her own hands. She was given a rat and a cage—a "Skinner box"—in which to train it. By selectively administering food during a series of repetitions, she taught the rat to look at, then approach, then press a lever. By the time she was done, the rat had learned to run straight to the lever as soon as it was put in the cage. She had made the animal do her bidding.

In 1966, she entered Stanford's graduate program in mathematical psychology. She might as well have walked into a men's locker room. She was the only woman admitted to the program that year. All her professors were men. Her classmates unanimously voted her least likely to succeed as a psychologist. They placed bets on when she'd quit. The betting pool turned out to be a damning test of mathematical psychology. Its abstract equations, designed to explain and predict behavior, couldn't account for the particulars of this young woman. She had lost her home and her mother. Compared with that, exams were easy.

She soon outgrew the boys' game. The deeper she waded into mathematical psychology, the less she liked its simplifications. People were more complicated than that. So was she. In her second year at Stanford, she was assigned to mentor an incoming student. She married him instead. On June 30, 1968, she became Elizabeth Loftus.

She thought she had found the love of her life. She would serve her husband's career, just as her mother had done for her father. But then she fell in love again. Not with a person, but with a field of study: memory.

Part III: Leading the Witness

In 1968, Elizabeth Loftus discovered what she wanted to do with her life. She wanted to experiment on people.

Loftus was 24. For several years, she had studied psychology and helped her professors with their research. She had been a cog in the academic system. But now, in her third year of graduate school at Stanford, she was finally getting a chance to design, run, and analyze her own experiments. She knew the thrill of training a rat to press a lever. But this was different. Now she was working with human beings.

Her topic was semantic memory. She was trying to find out how people's brains stored and retrieved words. She couldn't see inside their heads, but she could administer inputs and measure outputs, as she had done with her rat. The inputs were questions, and the output was response time. Sometimes she asked her subjects to name a "yellow fruit." Sometimes she asked them to name a "fruit that is yellow." On average, they answered the latter question a quarter of a second faster than the former. From this, she drew an inference: The brain organized such information by the noun, not the adjective.

Loftus loved the whole thing: conceiving the experiment, trying it out on people, measuring their performance, drawing conclusions about the mind. But not everyone was impressed. Shortly after earning her Ph.D., she had lunch in New York with her cousin, a lawyer. When her cousin asked about her work, Loftus proudly told her about the yellow-fruit study. Her cousin dryly asked how much it had cost the government.

The conversation stung Loftus. She was running her own memory experiments, but they were just about words. Why did it matter how people recalled yellow fruit? Wasn't there something more worthwhile to study?

What did she really care about? As an experimental psychologist, she decided to answer the question by studying her own behavior. What did she talk about when the topic was hers to choose? What did she like to bring up at parties? The answer was crime. She loved books, movies, TV shows, and news stories about it. Maybe she could become a crime expert. She could use the science of memory to help the justice system.

The first step was to find a project somebody would pay for. The Department of Transportation was offering money to study car accidents. Accidents weren't crimes, but they involved eyewitnesses, so she started there. She showed people films of collisions and quizzed them about what they had seen. Sometimes she asked how fast the cars had been going when they "hit" or "contacted" each other. Sometimes she asked how fast they had been going when they "smashed" into each other. The "smashed" question produced estimates 7 miles per hour faster than the "hit" question and 9 miles per hour faster than the "contacted" question. The questions were skewing the answers.

In another experiment, she showed her subjects a multi-car collision and asked some of them, "Did you see a broken headlight?" She asked others a leading version of the question: "Did you see the broken headlight?" Of the six questions posed in this dual format, three referred to things that weren't in the film. Compared with subjects who heard the question with an "a," those who heard it with a "the" were twice as likely to say they had seen a bogus item. (To experience one of Loftus' traffic experiments, click on the adjacent

Still, that was just lab work. Loftus wanted to get involved in a real court case. In 1973, after moving to the University of Washington, she called up the Seattle public defender's office and volunteered to help as a memory expert. In exchange, she got to watch the case unfold. It was a murder trial that hinged on conflicting memories over how much time had elapsed for premeditation. It ended in acquittal.

Loftus packaged her memory expertise with her accident studies in an article for Psychology Today. She challenged the reliability of eyewitness testimony, mentioned her work in the Seattle murder case, and noted that the defendant had been acquitted. It was practically an advertisement. Attorneys read the article and picked up their phones. Her career in legal consulting was launched.

She was exactly what defense lawyers needed. The chief threat to their clients was incriminating witness testimony. Loftus could shake the jury's faith in such recollections without attacking the witness personally. Memory errors were natural. The witness, like the defendant, was innocent. Even police, who caused misidentifications by contaminating witnesses' memories with mug shots and lineups, often didn't realize what they were doing.

Over the next 35 years, Loftus testified as a memory expert in more than 250 hearings and trials. She worked dozens of famous cases: Ted Bundy, O.J. Simpson, Rodney King, Oliver North, Martha Stewart, Lewis Libby, Michael Jackson, the Menendez brothers, the Oklahoma City bombing, and many more.

Why did a woman who had endured assault in her own life defend accused predators? Part of it was the structure of criminal law: Her work created doubt, and doubt was an ally of the defense. Part of it was her empathy for the accused: She had always been suspicious of criminal allegations and lenient toward small-time offenders. And where empathy failed, scientific rigor took over. Memory's fallibility was a fact. By testifying to that fact, she believed she was serving justice.

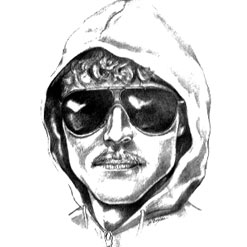

Loftus alters Lesley Stahl's eyewitness memory

Her job was to explain how memory errors could contaminate eyewitness testimony. For example, when eyewitnesses were shown lineups of possible culprits, they sometimes selected a face that was familiar for a different reason. Loftus demonstrated this by showing experimental subjects six photos while they listened to a crime story. One photo depicted the culprit; the others depicted innocent characters in the story. Three days later, she showed the same subjects a photo of one of the innocent characters along with three photos of other people. From these four pictures, she asked them to pick the criminal. Twenty-four percent of the subjects correctly refused to pick a photo. Sixteen percent picked one of the three new photos. Sixty percent picked the photo of the innocent character. They remembered it from the crime story but confused it with the perpetrator.

Police lineups worsened this confusion. In another experiment, after watching a mock crime, subjects were offered a lineup that didn't include the perpetrator. One-third of them picked somebody anyway. But when the cops conveyed extra confidence—"We have the culprit and he's in the lineup"—78 percent of the subjects picked somebody.

Then there were prosecutions based on coached child testimony, such as the McMartin Preschool sex-abuse case. To measure children's suggestibility, Loftus and a colleague showed them several one-minute films, followed by leading questions. "Did you see a boat?" they asked one child. Afterward, the child remembered "some boats in the water." "Did you see some candles start the fire?" they asked another. "The candle made the fire," the child said later. Other kids, after being asked about bees and bears, recalled bees and bears. None of these things—bees, bears, boats, candles—were in the films.

Not even Loftus was immune to suggestion. In 1988, after 13 years of testifying about memory's fallibility, she was told by her uncle that she was the one who had found her dead mother in the swimming pool. The sights and sounds of that awful morning came back to her—the corpse face down, the nightgown, the screaming, the stretcher, the police cars. But within three days, her uncle recanted the story, and other relatives confirmed that her aunt, not Loftus, had found the body. The memories of the memory expert were false.

The incident strengthened Loftus' conviction that such recollections shouldn't be trusted in court. The more cases she saw, the more passionate she became about her work. She saw herself as Oskar Schindler, rescuing as many innocent souls as she could. "The beauty I find in helping the falsely accused is something I like about myself," she wrote in an essay years later. "It's the deeper part of who I am."

The passion and the work took their toll. In court, she endured cross-examination and vilification. And at home, her husband gave up competing for her attention. In 1991, they divorced.

But by then, she had a bigger problem.

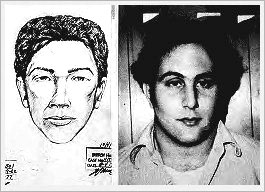

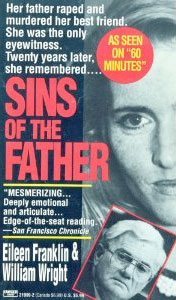

Part IV: The Recipe

In the summer of 1990, Elizabeth Loftus got a phone call from an attorney in San Francisco. A man named George Franklin had been charged with murdering a child, based on the recollection of his daughter, Eileen. Loftus, a psychologist, had testified in dozens of cases about the fallibility of eyewitness memory. But this case was different. The murder had happened 21 years earlier. Eileen's purported memory, however, was less than a year old. According to the prosecution, she had repressed it.

Repressed? How could such a crucial memory vanish for 20 years, leaving its owner completely unaware of its existence, and then resurface in full color? Loftus had her own bad childhood memory—being molested when she was 6—but she had never purged it. She searched the psychological literature and found no basis for the repression theory. George Franklin's attorney had a different theory: Eileen Franklin had never seen the crime. In her head, she had blended details of the murder, as it was reported in the press, with an imaginary picture of her father doing it. She had developed a false memory.

At the trial, Loftus explained how memories naturally eroded over time and became susceptible to distortion. She told the jury about an experiment in which she had shown people a video of a robbery and shooting. After the video, the viewers had watched an erroneous television report about the shooting. When they were asked afterward to describe the incident, many of them blended false details from the television report with their recollections of the video. They clung to these altered memories even when the experimenters suggested that they might be mistaken. Something like that must have happened to Eileen Franklin.

In previous cases, such testimony had swayed juries. But not this time. The prosecutor forced Loftus to admit that she had never studied memories like Eileen Franklin's. Loftus had proved that people could misidentify random perpetrators, not that they could mistakenly accuse their own fathers. She had proved that memories could be altered, not that they could be wholly invented. Her work seemed irrelevant. In November 1990, George Franklin was convicted.

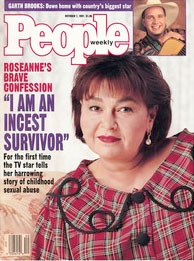

The nightmare was just beginning. Repressed memories were surfacing everywhere. In June 1991, Marilyn Van Derbur, a former Miss America, told the world that at age 24, she had discovered her father's sexual abuse of her as a child. Later that year, Roseanne Barr claimed to have recovered 30-year-old memories of both parents molesting her. ("He used to chase me with his excrement and try to put it on my head," she said of her father.) Women were suing their parents for millions of dollars. Hundreds of accused families sought help.

If these memories weren't real, where were they coming from? Eileen Franklin claimed that her memory had surfaced during hypnosis, therapy, a dream, or a flashback. Barr said hers had emerged during individual and group therapy.

Loftus began to read popular books that told women and therapists how to recover memories of sexual abuse. The books urged therapists to ask their clients about childhood incest. They listed symptoms that supposedly indicated abuse even if it wasn't remembered. They invited women to search for memories by imagining the abuse. They encouraged group therapy in which women could hear one another's stories of being victimized.

These ideas sounded fishy. Suggestion, indoctrination, authority, inference, imagination, and immersion were known to alter memories in police interrogations and experiments. But could they create a whole memory? Could the recent surge of incest recollections be the product of recovered-memory therapy?

To find out, Loftus went to a talk by George Ganaway, a respected psychiatrist, at the American Psychological Association's annual meeting in August 1991. Armed with case studies, Ganaway argued that "iatrogenic implantation"—implantation by therapists—was creating false memories of satanic ritual abuse.

Loftus suspected the same phenomenon was creating incest memories more broadly. But how could she expose it? In her book, The Myth of Repressed Memory, she described her next thought:

"While I couldn't prove that a particular memory emerging from therapy was false, perhaps I could step around to the other side of the problem. Through careful experimental design and controlled studies, perhaps I could provide a theoretical framework for the creation of false memories, showing that it is possible to create an entire memory for a traumatic event that never happened."

This was a pivotal decision. Loftus wasn't a detective. She was a designer of experiments. She couldn't start with seemingly recovered memories and demonstrate that they were false. But she could start with false memories and demonstrate how they were seemingly recovered.

Piece by piece, she analyzed and incorporated her adversaries' methods. For example, she noted in her book, "to parallel the therapeutic process, the memory had to be implanted by someone the subject trusted and admired, either a relative, friend, or a respected authority figure." That insight led to what became known as the "lost-in-the-mall experiment." (For more on the genesis of this experiment, see Part 2.) Each subject was given summaries of four incidents from his childhood. Three stories were true; one was false. The false story followed a formula: You got lost in a mall or department store, you cried, you were found by an old person. The summaries were written with the help of older relatives who knew the true incidents and the family. One woman, for example, was falsely told:

You, your mom, Tien, and Tuan all went to the Bremerton K-Mart. You must have been 5 years old at the time. Your mom gave each of you some money to get a blueberry Icee. You ran ahead to get into the line first, and somehow lost your way in the store. Tien found you crying to an elderly Chinese woman. You three then went together to get an Icee.

Loftus speaking at the Beckman Center, March 2007

The subjects were told that their relatives had recalled all four incidents. They were asked to fill in the details of each incident or, if they couldn't remember it, to write, "I do not remember this." In follow-up interviews, they were asked to think more about each incident and to retrieve any additional details they could recall. Of the 24 people subjected to this procedure, six came to remember the fake story as true.

From this experiment, Loftus began to sketch what she called a "recipe" for planting memories. First, you needed the subject's trust. A therapist had that; so did a family member. Then, by suggesting that the incident might have happened, you planted a seed. The subject would think about it, and the idea, if not the scene, would start to become familiar. The people and places mentioned—Tien, blueberry Icees, the Bremerton K-Mart—would evoke real memories, and these would begin to blur with the suggested scenario. By coaxing the subject to imagine the scene, you could accelerate this confabulation. Gradually, she would add details, seizing authorship of the story and securing its authenticity. The fabrication was out of your hands now. The memory was hers.

Loftus speaking at the Beckman Center, March 2007

This recipe was what the incest-survivor books were unwittingly teaching. It was what the recovered-memory therapists, with equal folly, were practicing. They hooked their readers and clients with checklists of supposed symptoms: headaches, guilt, low self-esteem, fear of darkness. Then they induced collaboration. "Let yourself imagine or picture what might have happened to you," said one book. "Occasionally you may need a small verbal push to get started. Your guide may suggest some action that seems to arise naturally from the image you are picturing." The guide, a therapist, supplied personal knowledge to help the process along. Group therapy helped, too. The more incest memories a woman heard, the more plausible her own victimization became. The more images she absorbed, the easier it was to picture the scenes she had repressed.

The mall experiment had obvious flaws. It involved only 24 people. Getting lost was different from being sexually abused. And maybe the six people who bought the story really had gotten lost in a mall, even if their parents or siblings didn't remember it. So Loftus ran bolder experiments with more subjects, more trauma, and greater implausibility. She convinced people that they had nearly choked, had caught their parents having sex, or had seen a wounded animal after a bombing. Other researchers planted memories of nearly drowning, being hospitalized overnight, and being attacked by an animal. In one study, Loftus and her collaborators persuaded 18 percent of people that they had probably witnessed demonic possession.

Loftus speaking at the Center for Inquiry's World Congress, April 2009

Critics protested that Loftus still hadn't proved the memories were fake. So she raised the ante. She persuaded 16 percent of a study population that they had met Bugs Bunny at Disneyland. In a follow-up experiment, researchers sold the same memory to 36 percent of subjects. This was impossible, since Bugs belonged to Warner Bros., not Disney. When critics complained that the Bugs memory wasn't abusive, Loftus obliged them again. Her team convinced 30 percent of another group of subjects that on a visit to Disneyland, a drug-addled Pluto character had licked their ears.

With each escalation and success, Loftus turned the tide of the cultural and legal war over repressed memories. Her experiments became potent evidence in court. Psychologists, judges, and initially credulous news organizations became skeptical of repressed memories. Many women retracted allegations of abuse. Lawsuits and regulators began to punish reckless therapists. The frenzy subsided.

For her courage in confronting this menace, Loftus was ostracized by clinical psychologists, denounced as an enemy of women, and accused of molesting her own children, though she had none. Armed guards accompanied her at lectures. And when she dared to reinvestigate a particularly compelling allegation of sexual abuse—the "Jane Doe" case—her university seized her files and barred her from publishing or discussing her findings. She persisted in the face of these ordeals because she refused to live in a world of lies.

That was the story she told about herself in books and interviews. And it was the truth. But not the whole truth.

Memory and Truth: The Mystery of Jane Doe

In the spring of 1997, an allegation of child sexual abuse shook up the debate over repressed memory. For several years, recollections of child abuse, ostensibly "recovered" in therapy, had been under attack in courtrooms and scientific journals. According to skeptics, these memories weren't real; they were unwitting products of suggestion and imagination. But this case was different. The alleged victim, known only as Jane Doe, had described the abuse on videotape at age 6 and again at age 17. In the second video, she appeared to recover the original memory. And this time, the memory couldn't be dismissed as a recent fabrication. Its corroboration was right there on the original tape.

Believers in repressed memory finally had their smoking gun. Expert witnesses began to present the case in court, citing it as proof that such memories were real. The tapes impressed many skeptics. But they didn't convince Elizabeth Loftus, the psychologist who had led the campaign to discredit repressed memory. She refused to believe that two stories told by the same witness could corroborate each other. Loftus suspected that Jane Doe, like other accusers, was under the spell of a false memory. But the memory hadn't been planted in Jane the teenager. It had been planted in Jane the child.

Loftus understood that the past could be opaque. When she was 14, her own mother had drowned, either by accident or suicide. Loftus would never know which, and she had learned to accept that. As an expert witness in dozens of trials, she had made her peace with mystery. To acquit a defendant, reasonable doubt was enough.

But this mystery had to be solved. The power of the videotapes and the use of Jane's story in other court cases demanded an answer. What lay behind the tapes? What had really happened to this little girl? Loftus had to know. She had to leave her laboratory and become a detective.

Jane had accused her mother of abusing her. From the tapes, Loftus ascertained Jane's home county. She hired a private investigator to get records from the local courthouse. Using databases, obituaries, and Social Security death records, Loftus and a colleague, Melvin Guyer, identified Jane's father. They scoured files from the custody fight between Jane's parents. They found a psychological evaluation and a Child Protective Services report that cast doubt on Jane's story. They interviewed local doctors and nurses to debunk the medical evidence against Jane's mother.

Loftus interviewed Jane's mother at her home. She spent four hours with Jane's foster mother. Finally, she tracked down Jane's stepmother. She learned that Jane's brother, who was alleged to have witnessed the abuse, had denied it. She discovered that Jane's mother had cooked on a gas stove, which couldn't have caused the coil-shaped burns Jane had attributed to her.

Gradually, Loftus and Guyer pieced together a theory. The psychologist who evaluated Jane as a child had questioned whether the abuses were real or had been "communicated" to her. "She has told her story numerous times to a number of different people and she now sounds mechanical," his report noted. This matched a comment from Jane's stepmother. "That's how we finally got her—the sexual angle," the stepmother told Loftus, referring to the custody fight she and Jane's father had waged against Jane's mother. "We were building a case against this woman. We were going for broke."

From legal records, Loftus determined that the stepmother was the first person to whom Jane had reported her abuse. With that, the puzzle pieces fell into place. Loftus and Guyer surmised that Jane's accusations "may have originated in the mind of StepMom and were communicated to Jane" prior to her first taped interview. Jane's memory at age 17 was an honest retrieval of her original story. But the story was false.

Before Loftus could publish her report, Jane Doe struck back. She told Loftus' employer, the University of Washington, that Loftus had violated her privacy. The university seized Loftus' files and barred her from publishing or discussing her findings. It took Loftus two years to win a letter of exoneration and another six years to get rid of Jane's subsequent lawsuit, which went all the way to the California Supreme Court. By then, Loftus, furious with the University of Washington, had moved to the University of California at Irvine. In their report on Jane Doe, published in the Skeptical Inquirer in 2002, Loftus and Guyer affirmed their duty to uncover "the whole truth" and presented the results of their investigation.

Part V: Truth or Consequences?

By the turn of the century, Elizabeth Loftus was the world's most influential debunker of false memories. She had rescued defendants from mistaken eyewitness testimony and from the pedophile witch hunt of the repressed-memory movement. But two dangers lurked at the core of her work. She was learning more and more about how to manipulate beliefs. And her allegiance to truth was negotiable.

In 1989, when the Chinese government tried to alter memories of the Tiananmen Square massacre, Loftus used her knowledge of brainwashing to expose the deception. (For more on this episode and her writings on politics, see George Orwell's 1989.) In the case of Jane Doe, an alleged victim of child abuse, Loftus risked her career to find out what had really happened. And in her books about witness testimony and repressed memory, she drew her moral power from truth. She wrote with dismay of the "horrifying idea that our memories can be changed, inextricably altered, and that what we think we know, what we believe with all our hearts, is not necessarily the truth." Quoting a fellow psychologist, she warned readers not "to accept a false reality as truth, for that is the very essence of madness." Memory was truth's guardian, and Loftus was memory's guardian.

But this picture, too, was part myth. Alongside the official story of her career, there was a shadow story. Loftus never believed in the absolute sanctity of truth or memory. She believed that memory, through wishful thinking, constantly modified itself. People remembered themselves as having given more to charity than they really had. They mentally airbrushed their behavior in marriages and relationships. They minimized what they had lost and embellished what they had chosen.

Like the clipped-on portions of Loftus' adolescent diary, memories could be conveniently adjusted. And this rewriting of history was no perversion. It seemed to Loftus such a common tendency that it must be a product of evolution. In short, it was natural. Its function, she surmised, was to promote happiness or, at least, to avoid depression. And this theory matched her reflections about her own life and the lives of her friends: Often, happiness was more important than truth.

In court, Loftus never consciously faced this question. There, she believed, truth and happiness overlapped. False memories on the witness stand sent innocent people to jail, and this terrible consequence was unacceptable. But her faith in the rightness of her cause sometimes numbed her to the manipulative games defense lawyers played. In fact, Loftus was very good at these games. And, for a while, she played them. She left truth to fend for itself.

The most important game was jury selection. As attorneys became familiar with Loftus' expertise in psychology, they recruited her to be a jury consultant. Her job was to present the anticipated prosecution and defense arguments, in summary form, to several hundred people. Each respondent had to render a verdict. It was like political polling, but with a twist: Using the respondents' demographic data—age, occupation, sex, race, income—the consultant would compute which kinds of jurors the defense should seek or exclude. On a few occasions in the late 1970s and early 1980s, Loftus did such work. She didn't love it, but she didn't refuse it, either.

In articles for legal journals, she deployed her expertise in juror psychology and her knowledge of how to alter beliefs. She counseled attorneys on jury selection and on coaching economists as expert witnesses to win bigger damage awards. In one article, she and a co-author suggested that lawyers might wish to "eliminate better-educated jurors who could serve as leaders in arguments against their clients."

Loftus wasn't a mercenary. She was just good at calculating the angles, and she didn't think anything terrible was at stake. The same was true of her work on advertising. In 1976, the Federal Trade Commission asked her to assess the power of ads to mislead consumers. She astutely dissected marketers' tactics, but she was equally capable of teaching them. A few years after the FTC job, an ad agency hired her to figure out how to get people to remember its client's product. There was nothing sneaky about the assignment. It was just a chance to use her talents and enjoy being wined and dined.

Loftus didn't care about ad consulting, so she didn't pursue it. But by the mid-1990s, her work on memory distortion was well-known, and others could see its business value. In 1996, she was approached by Kathryn Braun, a doctoral student in marketing. Starting in 1997, they collaborated on several articles about advertising's power to alter memories. They called this power insidious, warned that people should be educated about it, and stipulated that they didn't support intentional editing of consumers' pasts. But they also highlighted the "managerial opportunities" it presented.

Braun, Loftus, and their co-authors always disavowed deception. Yet they spelled out, for readers of Psychology & Marketing and the Journal of Advertising, exactly how their findings could be exploited. They analyzed which recollections were "better suited for memory revision": childhood memories in the case of Disney, college memories in the case of beer. They noted that since memory was fallible and malleable, advertisers could win back consumers who thought they'd had bad experiences with their products. From the advertiser's standpoint, they wrote, "you want the consumer to be involved enough that they process the false information" but "not so involved that … they notice the discrepancy between the advertising information and their own experience."

To illustrate the technique, Loftus and Braun drew up fake "Remember the Magic" print ads for Disney theme parks. The ads reminded readers of the parks' sights and sounds: Cinderella's castle, Space Mountain, meeting Mickey Mouse.

The researchers showed these ads to a group of college students, while other students saw a non-Disney ad instead. To ensure that the Disney ads wouldn't trigger true memories of shaking Mickey's hand, the researchers screened out students who reported up front that they had met a TV character at a theme park.

Of the students who were shown an ad featuring happy memories of meeting Mickey, 90 percent later reported increased confidence that this event had happened or might have happened to them. That was twice the percentage who reported such an increase in the control group. And compared with the control group, those who saw the Disney ad were significantly more likely to say that they fondly remembered visiting the park and that such visits had been central to their childhoods. Many who saw a different version featuring Bugs Bunny were convinced that they had met him at Disneyland, even though this was impossible, since he was a Warner Bros. character. (See Part 4.)

In a subsequent article for the Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly, Loftus, Braun, and Braun's husband (Braun, having added her husband's surname, was now Kathryn Braun-LaTour) demonstrated "how to employ reconstructed memory to help restore a brand damaged by a crisis." Using similar mock ads, they planted recollections of happy childhood visits to Wendy's: playing on the slide, jumping in the ball pit, swinging on the swing sets. These recollections couldn't be true, since Wendy's had never had such equipment. Compared with subjects who were shown an ad offering a free Frosty, those who were shown the happy-childhood ads reported that they had visited and enjoyed Wendy's more as children, including the fictional Wendy's Playland. The authors concluded that "it is better to engage consumers emotionally after a crisis situation than to appeal to their rational side."

If Loftus didn't condone memory tampering, why was she explaining how to do it? In part, she was just doing as she had been trained. You had to get published, and publishers wanted value for their readers. When you wrote for therapy journals, you offered advice to therapists. When you wrote for legal journals, you offered advice to lawyers. When you wrote for advertising journals, you offered advice to advertisers. That was how the game was played.

But Loftus was more than a trainee. She was a trainer. She had learned how to make people remember and believe things, and this knowledge was as useful to advertisers as it was to lawyers. Her only qualm about manipulation was that people might be harmed. And advertising didn't strike her as terribly harmful. Most advertisers, she and her colleagues noted, were "unlikely to try to plant a negative memory, as has been the issue with false memories of childhood abuse."

That was why Loftus treated advertisers more kindly than she treated recovered-memory therapists. The therapists' motives might be better, but the memories they planted were worse. Welfare, not honesty, was her god.

But in that case, what if you could help people by deceiving them?

In her curious mind, the idea was already brewing.

Memory and Politics: Orwell's 1989

In June 1989, the Chinese army crushed a protest in Beijing's Tiananmen Square with tanks and live ammunition, killing hundreds of people. Then the government washed out the massacre with propaganda. It told its citizens that the dissidents had assaulted the soldiers.

Watching these events from the safety of the United States, Elizabeth Loftus recognized the regime's strategy. It resembled the memory-distortion techniques she had researched as an experimental psychologist. Time was dissolving authentic memories of the uprising, and the regime was substituting its version by inducing people to repeat it in public seminars. "The Chinese government strategy of 'political reeducation' takes advantage of these features known to coerce memory modification," she wrote:

Each class member makes a public pledge of allegiance to the "lie." All the right psychological high-tech ingredients are in place for the lie to become the truth, reason enough for us to view the future of memories of Tiananmen square with foreboding pessimism. If handled skillfully, the power of misinformation is so strong and controllable that a colleague and I recently postulated a not-too-distant "brave new world" in which misinformation researchers would be able to proclaim, "Give us a dozen healthy memories, and our own specified world to handle them in, and we'll guarantee to take any memory at random and train it to become any type of memory that we may select …"

Actually, this unfolding dystopia wasn't Brave New World. It was 1984, George Orwell's novel about a totalitarian state controlling its population through memory revision. Loftus saw this threat becoming real. Manipulations of memory were "assaults on its very essence," she wrote. "We should worry about whose memory is next. Memory, like liberty, is a fragile thing."

In later years, Loftus returned to this theme. She criticized rosy history textbooks, political spin rooms, and photographic tampering by authoritarian regimes. "Are these simply memory distortion techniques applied on a grander scale?" she asked.

Then photo tampering hit home. In 2003, the Los Angeles Times published an Iraq-war photo that had been doctored for aesthetics. A year later, London's Daily Mirror ran fake pictures of British troops torturing an Iraqi prisoner. Another bogus photo, altered to pair John Kerry with Jane Fonda at an anti-Vietnam War rally, snookered American pundits and poisoned Kerry's public image as he emerged from the 2004 Democratic presidential primaries.

Intrigued by these fabrications, Loftus and two colleagues conducted an experiment to test whether doctored photos could modify political memories. They selected two famous protests: Tiananmen Square and a peace rally in Rome. To a photo of the Rome rally, they added menacing protesters and police in riot gear. To an iconic image from the Beijing uprising—a lone man blocking a column of tanks—they added throngs of people lining the route.

The revisions worked. Compared with subjects who saw the real photo of Tiananmen, those who saw the doctored photo were twice as likely to estimate that more than 500,000 people had participated. And compared with subjects who saw the real photo from Rome, those who saw the doctored photo were four times as likely to say that people had died in the protest. Loftus expressed alarm at the spread of photo manipulation, calling it "a form of human engineering that could be applied to us against our knowledge and against our wishes." "We have to figure how we can regulate this," she warned.

Last week, Slate tested the same techniques on political memories in the United States. We altered four images, took a fifth out of context, and mixed these five fake scenes (which involved Joe Lieberman, Dick Cheney, George W. Bush, Hillary Clinton, and Barack Obama), with three real ones. Half of our readers who participated in the experiment remembered the fabricated episodes as true, and when they were asked to guess which of the four incidents they had seen was fake, 37 percent picked the wrong one. The dangers of 1989 persist in 2010.

Part VI: The Road to Therapy

Elizabeth Loftus warmed to the idea of memory tampering for the best of reasons. She wanted to help people.

In her official career, as she described it in books, she studied the art of mental manipulation only to dissect, expose, and defeat it. Occasionally, she lent her psychological expertise to lawyers or advertisers for their self-interested purposes. But these purposes weren't hers, so she never turned them into a career.

To embrace memory tampering, she needed a purpose of her own. Something she could believe in and care about. Something that could put her skills to good use.

The story of how Loftus found that purpose—the story of her shadow career—began 30 years ago with a metaphor. "Imagine a world in which people could go to a special kind of psychologist or psychiatrist—a memory doctor—and have their memories modified," she mused in her 1980 book, Memory. This was no fantasy, she argued. The doctor was memory itself. "Every day, we do this to ourselves and others," she explained. "Our memories of past events change in helpful ways, leading us to be happier than we might otherwise be." Indeed, this was nature's design:

Why should we cling tightly to those memories that disturb us and spoil our lives? Life might become so much more pleasant if it is not marred by our memory of past ills, sufferings, and grievances. … We seem to have been purposely constructed with a mechanism for erasing the tape of our memory, or at least bending the memory tape, so that we can live and function without being haunted by the past. Accurate memory, in some instances, would simply get in the way.

The doctor, as Loftus initially conceived it, was just a metaphor. And that was how she presented it in her introduction. But by the end of the book, she was taking it literally. She proposed "to put the malleable memory to work in ways that can serve us well."

She envisioned this as a personal choice. "It would be nice," she mused, if each person "could decide whether he or she wanted to have an accurate memory versus a 'rosy' memory." But memory modification didn't work that way. If you knew a rosy memory was rosy, you wouldn't buy it. The memory had to be presented as accurate. The patient had to be deceived.

In 1979, as she was writing Memory, Loftus took her first steps in this direction. She and James Fries, a professor of medicine, published two articles calling for limits on informed consent to medical or experimental procedures. Through the power of suggestion, many patients developed side effects predicted by doctors. To reduce this problem, Loftus and Fries proposed (download) that anyone facing a procedure should be told its overall level of risk, but "detailed information should be reserved for those who request it. Specific slight risks, particularly those resulting from common procedures, should not be routinely disclosed to all subjects."

This wasn't really a withholding of information, they argued. The details would still be available on the back of a consent form. Anyway, it was impossible to tell patients the whole truth and nothing but the truth. And the purpose of informed consent, they reasoned, was to protect patients. Shouldn't patients be similarly protected from harmful hypothetical information?

The proposal seemed logical. But its logic didn't stop at relegating scenarios to the back of a form. If obscuring harmful information was good medicine, what about supplying helpful misinformation?

By 1982, Loftus was talking more seriously about therapeutic memory modification. "Since suggesting the idea of a memory clinic with memory doctors busily working on the minds of eager clients," she reported, "I have come across the writings of practicing therapists who suggest that the idea is not all that far-fetched." She wrote of therapists who were "creating entire personal histories in people. In this way, they enabled their clients to have experiences that would serve as the resources for the kinds of behaviors the clients wanted now to have." To encourage weight loss, for example, "the therapists created 'new childhoods' in which the clients grew up as thin people."

Memory doctors were no longer a fantasy. They were real. But Loftus didn't see herself as one of them. She was an experimenter, not a therapist. It wasn't until 1990, when she stumbled on the Eileen Franklin case, that she began to learn how to create whole childhood recollections. And by then, she was consumed by the dangers of memory tampering. The recovered-memory therapists were ruining people's lives.

To replicate and expose their fabrications, Loftus was busy planting bad memories. It was important but depressing work. One day, as she was explaining her research at a University of Washington colloquium, a colleague asked, "Have you ever thought about planting a positive memory? Maybe you could increase self-esteem."

Loftus hadn't thought of memory doctoring as a good idea in more than a decade. And now the idea struck her quite differently. It was no longer a mystery. It was her craft. She could do it.

Her first idea, cooked up over lunch with a friend, was to plant a memory of sitting on your grandmother's lap and being told that you were her favorite grandchild. Wouldn't that feel wonderful? But then she realized what would happen at the end of the experiment. As a research psychologist, she was ethically required to tell her subjects that the memory wasn't true. She couldn't bear to do that. So she dropped the idea.

Then another idea came along. Loftus had two junior colleagues studying imagination and memory. They were demonstrating that the act of imagining an experience increased people's confidence that the experience had really happened. Loftus tacked on a second experiment to see whether similar imagination exercises could increase healthy behaviors. The subjects were asked to imagine flossing and eating vegetables with dinner. It seemed to work: 24 percent of subjects later reported more flossing, and 40 percent reported more vegetable consumption.

In February 1997, Loftus unveiled her new line of thinking at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science. She explained how imagination could distort memory, and she conceded that this was often harmful. But rather than renounce the whole idea, she proposed to "harness the power of imagination and put it to some good use" by inducing healthier behavior. Instead of tampering with memories, she was proposing to take one component of the memory-tampering recipe—imagination—and use it for a completely different purpose.

Soon she was being flown to Washington, D.C., for a workshop organized by the National Institute on Drug Abuse. Its purpose was to figure out how behavioral science could inform behavior therapy. She presented her findings on imagination and memory, and the group discussed how this research could be clinically applied. Based on the presentation, Loftus and a colleague, Giuliana Mazzoni, wrote up a proposal and published it in the Autumn 1998 issue of Behavior Therapy.

Loftus had two models to work from. One was the accidental brainwashing recipe of the recovered-memory therapists. The other was her copy of that recipe, refined in the laboratory. All she had to do was tweak it.

The tweaked recipe, outlined in Behavior Therapy, was a procedure called Expert Personalized Suggestion. The patient's behavior would be changed through the power of suggestion, in the form of guided imagination exercises. She would envision herself flossing, for example, and would be promised better flossing habits as a result. This promise would be made credible by a tailored analysis of her personality. And she would accept the analysis and the suggestion because they came from an expert.

Loftus speaking at Beyond Belief, a conference of the Science Network, November 2006

The authors described this as "a novel procedure that capitalizes on what past research has intimated about the power of an authority figure, and the power of personalized suggestion, to influence people's thinking about their past." The past research, much of it conducted by Loftus, had focused on the danger of these powers. But the new procedure exploited them. It incorporated some of the tricks she had learned from the recovered-memory therapists, starting with pseudo-customized diagnosis. The diagnosis was actually scripted, and the expertise, as presented to the patient, was fraudulent. In fact, Loftus and Mazzoni called the whole thing a "therapy simulation." But instead of hurting people, it would help them. It would get them to floss, take calcium supplements, and avoid cigarettes.

There was one catch: The procedure wouldn't work if patients knew it was fake. They had to believe that the therapy, expertise, and personalization were real. "We probably would not wish to include the deceptive aspects of the methodology because it is not ethically acceptable to deceive a client," the authors conceded. But maybe this problem could be fudged: "Suppose after a short interview with [the patient], the clinician tells her that he proposes trying an imagination exercise that he is quite confident, given her interview, will lead her to increase her consumption of calcium. In a real sense this is a true statement," since imagination exercises, on average, did change behavior. If the simulation worked, it wasn't fake—was it?

With each innovation and rationalization, Loftus was building a technical and moral case for therapeutic trickery. But one ingredient was still missing from her recipe: memory.

Part VII: Training Humans

In 1998, when Elizabeth Loftus published her first behavior-therapy proposal, she stopped short of editing memories. The proposal, Expert Personalized Suggestion, was designed to exploit the self-fulfilling power of imagination, not to alter recollections. Loftus and her coauthor described memory modification as an unfortunate risk of the procedure. It might happen, they wrote, but only as a tolerable "cost" and "side effect."

To become a memory doctor, Loftus needed one more tweak. She needed to set aside her compunctions about memory tampering and redirect her mind-control skills from the future to the past.

It happened by accident. A few years after she published her EPS proposal, she began a new line of research, investigating whether false memories could affect behavior. The behavior had to be simple, measurable, influenced by memory, and testable in the lab. One obvious candidate was eating. Food aversions were common and powerful. You could plant a memory of a bad experience with a certain food. Then you could test whether this memory affected the subject's eating behavior.

Loftus' collaborators tried the experiment first with pickles and hard-boiled eggs. They asked subjects to fill out questionnaires about their food preferences. A week later, they handed out computer-generated reports telling each subject that he had, among other things, gotten sick as a child from eating one of the specified foods. The subject was told that the computer had drawn this conclusion from an analysis of his answers to the questionnaire. The procedure was like EPS, except that the expert was now a computer, and the suggestion was a false memory. After reading the reports, more than a quarter of the subjects said they believed or remembered the incident. When they were asked later about foods they might eat at a barbecue, those who were successfully duped indicated that they were more likely to avoid pickles or eggs.

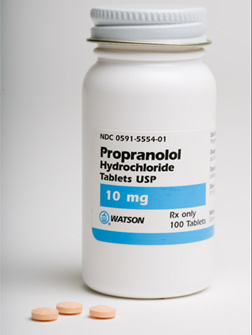

Loftus performing her food experiment on Alan Alda

When Loftus saw the results, an idea came to her. What if you could produce similar aversions to fattening foods? Could false memories help people eat a healthier diet? She tried the experiment again, first with potato chips, then with chocolate chip cookies and strawberry ice cream. The potato-chip version failed, apparently because potato chips were too familiar as a tasty snack. But the ice-cream version worked. More than 40 percent of subjects were persuaded that they had gotten sick eating strawberry ice cream, and these subjects were significantly more likely to say they would avoid it.

In February 2005, Loftus and her coauthors published the egg study, concluding that "humans can be trained to avoid food." Four months later, they published the ice-cream study under the title, "False Beliefs About Fattening Foods Can Have Healthy Consequences." The diet-improvement rationale, originally an afterthought, was now central. The bottom line, they wrote, was that "we can, through suggestion, manipulate nutritional selection and possibly even improve health."

In the food experiments, all the threads of Loftus' career came together. Instead of training a rat, she was training people. Instead of using a reward, she was using the techniques she had learned from the recovered-memory therapists. And instead of planting bad memories, she was planting healthy ones. She was a real-life memory doctor.

But she, too, was responding to behavioral reinforcement. The fattening-food experiment was the most widely celebrated study she had ever done. It made headlines all over the world and earned her a place on the New York Times Magazine's list of the year's most innovative ideas. She was being rewarded for doing something socially useful. She reveled in the attention and acclaim. She quoted her press clippings in speeches.

In reality, the work she had done on memories of sexual abusewas more important. But that work had hurt and angered people. It had brought condemnation and contempt on her. In diet therapy, she found no such punishment. Again, she was meeting people who desperately needed her. But this time, they were fighting obesity, not deluded daughters. "I wish I could be of more immediate help to these people, but I'm forced to tell them that the line of research is at its very earliest stages," she wrote in 2007. "Still, it is refreshing to be working on a topic that could indeed be of genuine help to people and one that is not as anger inspiring and dangerous as the topic of sex abuse."

Loftus speaking at Beyond Belief, a conference of The Science Network, November 2006

All those years, Loftus had been vilified for attacking therapy. Now she was inventing a therapy of her own. But hers was different. It was good for people, and she could make it better. She began to think of ways to magnify its power: ratcheting up the false feedback, perhaps, or showing photos or videos of people being sickened by the designated foods. Soon she was convincing students that they had loved asparagus as children. "Healthier Eating Could Be Just a False Memory Away," said the published journal article.

Loftus talked about the food experiments the same way she had talked about EPS. The concept, she explained, was to "tap into people's imagination and mental thoughts to influence their food choices." But two crucial elements had changed. First, she was now trying to influence behavior through memory, not just through imagination. In EPS, memory modification had been a kind of collateral damage. In the food experiments, memory modification was the whole idea.

Second, she was proposing permanent deception. Psychologists who misled people in experiments were ethically obliged to tell them the truth when the experiments were over. That was why Loftus had abandoned her original idea to plant a memory of being told by your grandmother that you were her favorite grandchild. Now Loftus was severing that obligation. Therapeutic memory modification, as she envisioned it, would be left uncorrected.

In her EPS proposal, Loftus had sketched an informed-consent script that she thought could be defended as truthful. You could tell the patient that imagination exercises would improve her behavior, and, sure enough, her behavior would improve. But that self-fulfilling trick worked only because the future was unformed. Claims about the past were different. To revise the past, you had to lie.

Loftus speaking at the Beckman Center, March 2007

Loftus didn't flinch at this step. "A therapist isn't supposed to lie to clients," she conceded. "But there's nothing to stop a parent from trying something like this with an overweight child or teen." Parents already lied to kids about Santa Claus and the tooth fairy, she observed. To her, it was a no-brainer: "A white lie that might get them to eat broccoli and asparagus vs. a lifetime of obesity and diabetes: Which would you rather have for your kid?"

She was correct: The memories she was planting would do more good than harm. The same could be said for EPS and for her old proposal to limit side-effect warnings. But her ideas were becoming steadily bolder. She was thinking less like a student and more like an engineer. She was becoming more willing to deceive and to redefine consent. She was trying not just to shape the future but to reshape the past. And she was noticing none of this. Memory therapy was coming from a place she had forgotten, and it was going somewhere she couldn't foresee.

Where would it stop? Should a line be drawn against altering the past? If so, where? Those questions were open to debate. But something unsettling had already happened: Loftus had crossed her own line without recognizing it.

Many years earlier, she had worked with survey researchers on a common problem: false behavioral reports. Deluded by rosy memories, people misrepresented their conduct. They underreported their sex partners, exaggerated their consistency in using condoms, and claimed better eating habits than they had really practiced. These delusions, in turn, skewed medical diagnoses and the surveys that informed nutritional science. To illustrate the danger, Loftus had sketched a scenario: Suppose researchers were interviewing women to identify dietary factors in breast cancer. If some of the women claimed to have eaten healthier food than they had really consumed, correlations between their outcomes and their actual diets would be obscured.

Now Loftus was planting precisely such memories. The problem wasn't just where to draw the line against memory modification. The problem was remembering where you had drawn it.

From food to alcohol: Loftus explores new frontiers in memory therapy

Undeterred, she plowed ahead. If memory therapy could change eating habits, why not drinking habits? With grant money from the National Institute on Alcohol and Alcohol Abuse, she and her collaborators moved on to alcohol, using the same method. In a report on their experiment, submitted in March 2010 to Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, they called their work "a first step in exploring the idea of using memory implantation techniques for the purposes of reducing or eliminating an unwanted behavior."

The list of unwanted behaviors was just getting started.

Memory, Sex, and Food: The Price of Error

False memories aren't just problematic in court. They cause trouble elsewhere in society, and particularly in medicine.

As Elizabeth Loftus became known for her work on memory errors, survey researchers sought her help in order to understand how such errors were skewing responses to questionnaires. In crime surveys, memory tended to exaggerate local crime rates, which, in turn, could distort the allocation of law enforcement. In political surveys, people falsely recalled having voted in previous elections, thereby polluting samples of "voters." The biggest area of concern was health behavior. People didn't accurately remember which diseases they'd had, which precautions they'd taken, or how often they'd brushed their teeth. As a result, they misled their doctors and skewed public health data.

Sex was a good example. Loftus and her colleagues found that people exaggerated their consistency in using condoms and underreported their sex partners. Consequently, such people underestimated their degree of risk. Loftus worried that this tendency would corrupt the personal medical histories doctors used to diagnose and prescribe treatment for patients. It would also mislead intervention programs by falsely minimizing problem behaviors.

Rosy memories plagued food research, too. A typical survey, Loftus and her coauthors noted, might ask, "How often have you eaten chicken in the last 12 months?" Again, self-flattering answers—people reporting that they had eaten more spinach or less chocolate than was really the case—could skew medical histories, distort the prevalence of risk factors, and lead public-health programs astray. They could also contaminate science. "Suppose, for example, that you are a researcher interested in the relationship between fat in the diet and the development of breast cancer," Loftus wrote. "You decide to interview a group of women who have developed breast cancer and a group that is cancer free, asking questions about their diets and eating habits." Some of these women "might exaggerate the amount of healthy foods they ingested and minimize the quantity of unhealthy, fatty foods that also made up part of their diet." As a result, "you would be led to the wrong conclusions."

And these were just memory's natural errors. By inducing additional errors, therapists could further distort public data. Suppose they persuaded their clients that the clients had been bullied as children. Such false memories, Loftus and her colleagues observed, might inflate estimates of the prevalence of bullying.

What if these two problems converged? What would happen if therapeutic distortion ventured into the realm of food memories?

Despite her own warnings, Loftus would soon lead the way.

Part VIII: The Future of the Past