The City and the Sea

Creating resilient new waterfronts in the wake of Sandy.

Photo by Allison Joyce/Getty Images

This essay originally appeared in the March/April 2014 issue of Orion, America’s finest environmental magazine. Request a free trial issue of Orion here.

Twenty years before Hurricane Sandy slammed into the slim spit of land that is New York City’s Rockaways, local artist Richard George was out planting trees. He was in his 40s then, and had shifted his home a few years earlier from Corona, Queens, to a 1920s bungalow colony in the Far Rockaways, abutting the Atlantic Ocean. He didn’t know anything about trees, had never given a thought to dune ecology or sea surges, but he’d joined the board of the local Beachside Bungalow Preservation Association, and a friend gave them $15,000. The directive was to plant trees, so that’s what he did.

“He planted the money in my hand,” George recalls when I meet him at his cottage, a bright white bungalow with turquoise trim that matches his T-shirt. “I said, ‘Where am I gonna plant trees?’ ” Then the artist saw the wide expanse of beach down the street, like a blank canvas in waiting.

George is convivial, a man who enjoys talking, which he’s doing at a rapid pace in a heavy New York accent as we head from the cottage toward the beach. It’s a clear spring day, making it hard to imagine the devastation that Sandy wrought when she landed on the shores of New York City, generating a 14-foot storm surge that dumped the Atlantic Ocean into thousands of homes, decommissioned trains, caused a Con Edison power station to explode, plummeted tracts of the city into darkness and others into fire, and took 43 lives. The storm cost an estimated $19 billion in damage and an unquantifiable amount of grief.

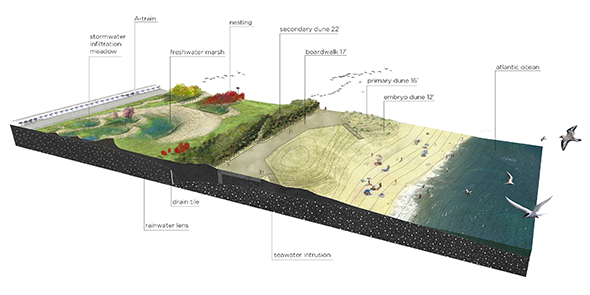

The street ends in a ramp that leads to an elevated boardwalk, rising a dozen feet above street level. In 1992, George tells me, you could walk right under the boardwalk with room to spare. Now, as we walk up the ramp to get to the length of the boardwalk, which was untouched by Sandy, we are surrounded on both sides by a dune so high that it’s packed against the bottom of the boards. It’s thick with plants, a seaside forest filled with bayberry, beach plum, autumn olive, wild rose, and Japanese black pine 15 feet tall. The first fiery hints of poison ivy inch out of the sand at toe level. This beach forest is what is considered a secondary dune; on the other side of the boardwalk, waves of beach grass cover the primary dune before sand takes over. The water appears so innocent, softly lapping onto the beach, sparkling in the sun.

Courtesy of Local Office Landscape Architecture

“At first, we just planted tiny little beach grass,” George tells me. He gathered up 35 volunteers, and they spent a couple of weekends planting the starts. “One blade, one blade, one blade,” he explains, his fingers poking into the air. Later, they planted trees.

In 1994, they got another $15,000 and planted more. This time they rented a machine to dig the holes, and a neighbor cooked the volunteers lunch. Once the plants became established—NYC Parks GreenThumb, which supports the city’s network of community gardens, helped keep them watered through that first vulnerable summer—residents and beach bums could sit back and watch the sand grow. And grow.

“The beach grass grew by itself,” he says, as he bends to show me the thick, matted root system, exposed at the edge where Sandy’s storm surge gnawed away half of the primary dune. He’d been standing in this very spot just five hours before the surge hit. The double-dune system that stretches for a few blocks on either side of George’s street seemed to help fend off Sandy’s deluge: The water breached on Beach 27th Street, where the dunes stop.

“The dunes were twice as high before the storm,” he says, looking at the remains of the sacrificial sands. “It saved us.”

* * *

Once upon a time, about 2 million years ago, the Pleistocene era locked up the world’s water in glaciers miles thick. Then, it warmed. It was about 10,000 years ago when the water of the melting glaciers was released to reshape the world into the coastlines we now associate with modern-day maps.

By all indications, though, the shape of those coastlines is about to change.

The archipelago of New York City’s five boroughs has almost 600 miles of littoral zone between solid ground and watery sea, a place of straits and river mouths, bays and beachy backshores. It’s also a place whose contours have been radically transformed by its citizens. A large percentage of the city’s edges were created artificially, filled in and built upon with the false confidence that land taken from the sea is permanently allocated for terrestrial use. But on Oct. 29, 2012, the record-breaking storm surge that swept over New York City flooded 51 square miles of that falsely allocated land—and like a finger from a watery grave, the high-water mark traced the coastline that once was and may soon be again. The mayor’s office says that, by the 2050s, 800,000 New Yorkers will live in hundred-year flood plains, double the current number.

In 2008, Mayor Michael Bloomberg convened the New York City Panel on Climate Change (NPCC), a multidisciplinary group comprised of academic and private-sector experts on everything from climatology to oceanography to law and insurance risk. Their task was to assess how climate change might affect the city and make suggestions about how to mitigate those effects. Sea levels vary around the globe, and models still vary wildly, but the NPCC settled on 48 inches—the average height of a 7-year-old child—as the informal figure for estimated sea level rise in the New York City area by the 2080s. They readily admit that this number is subject to change, especially if the polar ice sheets get caught in a feedback loop that speeds up the process.

Given the huge number of people who live on the world’s coasts, how will human populations—whether in Brooklyn or Bangladesh, Miami or Mumbai—adapt to an increasingly aquatic world? Do we stand strong and demonstrate our clever technical ingenuity with multibillion-dollar floodgates and waterproof buildings? Or do we humbly bid a hasty retreat, scrambling for higher ground while there’s still time, waving a white flag to Mother Nature?

It seems increasingly clear that there may be a third way: an approach that blends a trace of conciliation with an abundance of creativity, using hints from the ecological past to design the coastlines of the future—and it could be the key to surviving in coastal communities in an age of rising seas. The way forward will require an unlikely collaboration, not just between public institutions and citizens, but also between humans and the one player too often left outside, literally and figuratively: nature herself.

* * *

When it comes to prospects for human life within the increasing reach of the ocean, design answers fall into two categories, the soft and the hard, the yin and the yang. Dunes, wetlands, and oyster reefs fall on the soft side; hard is the stuff I know from my childhood on the Jersey Shore: tar-smeared bulkheads and jetties jutting out at perpendicular angles in an effort to staunch the natural movement of sand. A floodgate is as hard as it gets.

Speculation about the construction of a great surge barrier surfaced soon after Sandy. The largest proposed gate would run parallel to the expansive Verrazano-Narrows Bridge, nearly a mile long. Outright critics spoke of engineering cockiness, ethical and legal conundrums, disrupted harbor ecosystems, and a false sense of security. More cautious skeptics noted that comparisons with countries that do employ floodgates, like the Netherlands, fall short when one considers that the eastern United States routinely weathers storms the Dutch can’t imagine in their mild climate.

But instead of seeking out the big fix, most adaptation efforts are opting for a multifaceted approach. After Sandy, Bloomberg formed the Special Initiative for Rebuilding and Resiliency, and in June, it released a comprehensive 440-page report, “A Stronger, More Resilient New York.” In it, the city proposes more than 250 different initiatives that would strengthen everything from the energy grid to communications networks to transportation systems. A proposal for a great flood barrier is notably absent.

The city’s response echoes what is rising up like wrack on the high-tide line, a medley of ideas from all sectors across the boroughs and beyond. Many seek to embrace the best of technological advances and apply them in ways that foster, instead of resist, the fundamental laws of the natural world: Let the wetlands be wetlands, bird-festooned sponges. Remember the shape of New York’s native coastlines. Cultivate sand dunes and beach forests. If Richard George and the Beachside Bungalow Preservation Association could save a bit of coastline with 35 volunteers and a neighborhood cook, imagine what a whole country could do if it acted with nature in mind.

The U.S. has more than 12,000 miles of coastline, home to 53 percent of Americans. What can the rest of us learn about coastal infrastructure from the shorelines of America’s largest city? I’d come to the Big Apple to find out.

* * *

It is springtime when I visit the western end of the Road to Nowhere, where the legendary NYC Parks Commissioner Robert Moses, a ruthless mid-20th-century urban planner who favored parkways over parks, left his indelible mark on the Rockaways in Queens. Of the 5½-mile-long boardwalk that ran along the Rockaways beachfront, more than half was destroyed by Sandy, and afterward, the city spent more than $140 million to rebuild beaches. The work continues today. I see one man scrape his shovel across a basketball court, fill his wheelbarrow with sand, and walk a half dozen steps away to dump the contents on the beach; nearby, bulldozers move between the skeletal remains of the boardwalk’s concrete stanchions. Annually, dredges and offshore rigs vacuum up sand that is hauled onto the beach, where heavy machinery sculpts it into a shoreline in a continuous process called “nourishment.”

I turn my back to the men and take in the 2-mile length of Moses’s Shore Front Parkway. In 1939, Moses orchestrated the divided, four-lane parkway along the southern shore that was supposed to become part of a 90-mile road system along Long Island, linking the Hamptons in the east to Brooklyn in the west. (The project never came to fruition, hence the local nickname, Road to Nowhere.) But while Moses razed neighborhoods and built highways, a new generation of thinkers hopes to reshape the city with a gentler hand than the one he wielded. The Shore Front Parkway could be where it begins.

Watching the bulldozers do their work, I envision the space transformed into a system of forested beach dunes—it would be reclamation of the grandest sort. This is the idea of Walter Meyer and Jennifer Bolstad, the husband-and-wife team of Local Office Landscape and Urban Design, on-and-off Rockaway residents, and avid surfers. In the immediate aftermath of the storm, Meyer worked with others to form Power Rockaways Resilience, which delivered hand-built, shopping-cart-sized solar generators to the hardest-hit parts of the Rockaways so storm survivors could charge cellphones, laptops, and small power tools. The White House recognized him as a Champion of Change.

Courtesy of Local Office Landscape Architecture

Now, Local Office is looking long-term. They have set their sights on transforming the lingering Moses legacy of the Shore Front Parkway into a double-dune forest system, similar to what Richard George showed me on a small scale on the Rockaways’ eastern end. They propose downsizing the parkway from its current 80-foot width to a reasonable 30-foot road and using the new space to develop dunes planted with trees and shrubs that provide beachfront storm surge protection. The boardwalk would continue to exist, nestled between the primary and secondary dunes. They imagine a system like this stretching across the entire 15-mile length of the sea-facing Rockaways, a natural double-duty sea wall of sorts.

“This is a story about trees,” Meyer tells me. “It’s less about the dunes than what the dunes support, this coastal forest. It’s a living armor.” Globally, Meyer says that more and more nations are turning to softer approaches to dealing with sea-level rise. “The Dutch don’t build dykes anymore; they’re building sand bars and sand dunes,” he says. “The Japanese are building forests. The Australians are building reefs.”

By late 2013, the NYC Department of Parks and Recreation had commissioned Local Office for drawings, the first step for a pilot project that may bring the double-dune forest vision to life. Meanwhile, Meyer and Bolstad continue their community-based efforts, teaming up with reTREEt America, which plants in areas struck by disaster, to bring volunteers together to landscape with native plants on property where dunes are being developed. The most recent planting day evolved into a block party, where volunteers were plied with fresh fish and beer as homeowners gave their thanks.

* * *

“There are some parcels that Mother Nature owns,” New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo said in his State of the State address, a few months after Sandy. “She may only visit once every few years, but she owns the parcel, and when she comes to visit, she visits.” Nature—in the form of rising seas—has already begun to visit a stretch of the East Coast from Cape Hatteras to Boston, which is experiencing sea-level rise greater than the global average. And in 2013, the New York–area flood zone doubled when the Federal Emergency Management Agency released its new maps. Some scientists think that even this is a grave underestimate of coastlines at risk.

A bit of surrender, then, may be unavoidable. For Meyer and Bolstad’s double-dune forest to exist, for example, some would lose their ocean views and others perhaps their houses, houses that are so close to the ocean that there is no room to create a dune system. But the reality is that many of those houses were already relinquished, swept off their foundations during the storm in a sudden unplanned event that is the opposite of managed retreat.

The crooked flagpole that leans in the sand at the end of Kissam Avenue in Staten Island’s Oakwood Beach neighborhood is a reminder that a dune can only be battered so many times before it’s breached, and with rising sea levels, the concern is real. Most of the Fox Beach area of Oakwood has signed up for a buyout—at prestorm home values—that Cuomo proposed post-Sandy. The offer was impossible to pass up for many beat-up shoreline dwellers who lived in what was essentially a bathtub, vulnerable to storm flooding from the west, ocean surges from the east, and brush fires from the phragmites-filled wetlands that close in from the north and south. The whispering fronds betray a neighborhood that was once, and remains, a wetland.

“The storm would’ve killed me if I’d been home,” says resident Bill Bye, whose single-story bungalow on Kissam Avenue filled nearly to the ceiling with seawater during Sandy. When I meet him, Bill sits in a plastic lawn chair in front of his home of 30 years with a single sheet of paper in his left hand and a cigarette in his right. The paper is a New York City assessor sheet, which shows the value of his home before Oct. 29, 2012. He hopes the assessor will agree with the value and that the government will issue a check—soon—allowing him to move on with his life. “It’s gonna happen again,” he says. “It’s too dangerous to live here.”

But Oakwood Beach and its wetlands don’t have to signal disaster in waiting. The area is also part of a growing system known as the Staten Island Bluebelt. Run by the NYC Department of Environmental Protection, the Bluebelt is the aquatic equivalent of a greenbelt. The extensive system of engineered ponds, creeks, and wetlands naturally provides flood control by absorbing storm surges across 10,000 acres and 16 watersheds that span the southern end of the borough, Oakwood Beach among them.

Yet the word engineered evokes the wrong visual. Instead, imagine Staten Island circa 1850, with babbling brooks passing under stone bridges and along banks blooming in purple-flowered pickerelweed. Bluebelt designers, who use words like beautification and countrify to describe their work, draw their inspiration from mid-19th-century photographs and native plant stock, as well as the latest knowledge of hydrological dynamics: strategically placed riffles and pools along with abundant plantings help soak up storm runoff pollutants like nitrogen and phosphorous. A moratorium on new building in wetlands along with buyouts like the one in Oakwood Beach are helping to expand the Bluebelt’s reach. “This is what some people like to call ‘thinking out of the box,’ ” says former Staten Island borough president James Molinaro. “Instead of putting down sewers, you use nature to purify and disperse storm water. There’s both beauty and effectiveness.”

The Bluebelt costs considerably less than a typical underground sewer system, and it provides the added benefit of fostering community open spaces and wildlife habitat. Neighborhoods can “adopt” a piece of the Bluebelt, and volunteer groups help with cleanups. The result is an ecosystem-wide maintenance program that brings together citizens and government in a creative way that is winning awards.

* * *

Another unlikely but increasingly sensible partnership for a livable New York is between humans and a more aquatically sophisticated member of the natural world—oysters. The city’s waterways were once dense with them. Jamaica Bay alone, a vast network of wetlands and marshes on the north side of the Rockaways, used to send 300,000 bushels of oysters to city markets each year. But by 1921, the impacts of sewage and industrial effluent, overharvesting, and dredging had taken a toll, and the oyster beds perished or, for health reasons, were no longer harvested.

Now, New York City waters are cleaner than they’ve been in decades, and spat—the little larvae of oysters—are floating about, seeking out some substrate to latch on to so they can grow.

“There are oyster larvae,” says landscape architect Kate Orff. “There’s just no place for them to land. So there are these babies, but then ... ” She pauses and makes a long downward whistle indicating failure. “I get depressed about this, as a mom of two.”

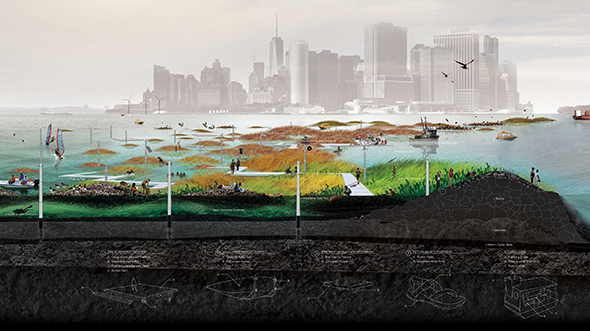

Orff has proposed bringing back New York City’s lost oyster reefs—which could naturally help shield the city from future storm surges—in a project called Oyster-tecture. We meet at a round table in the kitchen of her SCAPE Studio offices on Lower Broadway, with a foggy morning view across Manhattan to the Hudson River.

Courtesy of SCAPE Landscape Architecture

Her idea is to make a home for the oyster orphans, starting in Brooklyn’s Gowanus Canal, one of the most polluted waterways of the city. Piers are already in place; cages will be lowered into the water that are filled with fuzzy rope, providing lots of surface area for spat to land. (The cages are to keep hungry New Yorkers from prematurely harvesting oysters that won’t be suitable for human consumption for years to come.) She was thrilled when she heard Cuomo give a shout-out to the bivalves after the storm: “It came out of his mouth—‘We need to be thinking about oyster beds’—and I’m like, yes, that’s the goal!”

Orff advocates dredging and filling waterways in a way that supports underwater ecosystems instead of destroying them. “I think a big part of this is thinking about it holistically,” she says. “You can use dredging and filling in a cut-and-build concept throughout the harbor to create a new set of edges and cross-sections that can become armatures for habitat.” As the oysters build upon themselves, making reefs out of their own shells, they work continually to clean the waters, acting as natural filtration systems.

To consider the return of oyster reefs to New York is to explore the bathymetry, or underwater topography, of the waters that surround the city’s islands. Orff explains the mechanics, but it’s as much a history lesson.

“There was once this historic 3-D mosaic of underwater bathymetry, which included barrier islands and oyster reefs and shallower shoal areas that make a threshold into the inner harbor,” she says, using a marker to show how the stretch of Sandy Hook on the Jersey Shore wants to reach up and connect with Coney Island in a series of channels and shoals. If the land mass was permitted to form again, it would help diminish the impact of sea surges. One hard passageway could allow a steady shipping channel. “See this signature?” she taps her marker on the area between Staten Island, Brooklyn, and New Jersey. “This whole area was once shallows, back in 1766, fortified with layers of ecological systems.”

Orff isn’t the only person in the city thinking about oysters. Marit Larson, the NYC Parks Department’s director of wetlands, is working on oyster restoration on the north side of the city. She says that, increasingly, oysters have been showing up on tires and concrete rubble in the Bronx River. In 2006, the Parks Department started designing artificial reefs to supplement the river’s substrate; now they’re working with partners that include NY/NJ Baykeeper and New York Harbor School, which trains low-income kids in hands-on maritime stewardship as they dump 120-ton loads of shells into an area where the East and Bronx rivers converge. One survey taken just before Sandy struck found more than 11,000 oysters along a milewide swath of water. Last summer, students relocated another 100,000 farm-raised spat to the growing reef.

When referencing historical patterns, Orff refers repeatedly to something called the Ratzer map. In 1766, 10 years before the rebellious colonists unshackled their new nation from the British empire, cartographer Bernard Ratzer was trolling the New York Harbor, recording its curves and depths. His sepia-toned map now hangs at the Brooklyn Historical Society, a memory of the city’s once-flourishing natural infrastructure that, if brought back to life, could help mitigate the type of damage experienced during an event like Sandy.

Orff’s pen sweeps across her drawing. “This is a diagram of an ideal world of nature’s protectors. You have layers and layers of barrier dunes, and then vast tracts of wetlands. Wetlands don’t make sense if you have a building and only a little wetland. Wetlands only make sense if they are extensive, so they can really dissipate wave energy.”

Of course, efforts like these can only do so much to counteract the effects of climate change. But if combined with a comprehensive rebuilding of New York’s natural features, they could make a real impact. “There is literally nothing that could have stopped the Sandy surge,” Orff says. “But hard and soft infrastructure solutions could be combined in a win-win-win scenario that would revitalize the harbor landscape, clean the water, and begin to address coastal protection.”

* * *

The Ratzer map some clues to what a more resilient New York might look like, but it’s a static snapshot compared to the Mannahatta Project, which documents the changes to Manhattan island that have occurred since that fateful year of 1609, when the explorer Henry Hudson first sailed his vessel, the Half Moon, into New York Bay. The project, now extending to all five boroughs and renamed the Welikia Project, is the work of Eric Sanderson, senior conservation ecologist with the Wildlife Conservation Society. Sanderson spent more than a decade piecing together the city’s original ecology, mapping where its creeks once flowed, what its shoreline once looked like, and which flora and fauna filled the ecosystem. The results are a roadmap for designers seeking to know what was, in order to guide what will be. Because there is no indication that we humans will stop tinkering with our environment, the hope is that the adaptations we make embrace the third-way approach that balances human needs and ecological limitations.

“Constructing human habitats that work with nature rather than against it will have the greatest benefit for people and nature,” Sanderson says. “Probably the most important work to be done, but also the hardest, is adapting the social, legal, and economic institutions to incorporate messages from the natural world.”

Even with those systematic challenges, Sanderson is solid in his belief that we can learn—and benefit—from listening to what the natural world is telling us.

“Hurricane Sandy was information encoded in a storm,” he says. “If people begin to see the nature of our place, then they can begin to see the landscape strategies that history suggests are protective and adaptive over the long run: specifically, a combination of beaches, dunes, and salt marshes.”

The process of reimagining New York City’s infrastructure with climate change in mind was underway before Sandy, but the storm’s devastation underscored the urgency of learning from nature and then planning and designing with her machinations in mind. There will be some managed retreat—some withdrawal from coastal areas that one hopes will be graceful—but there are also ways to stay along our shorelines safely. It demands rethinking the meaning of edge, redefining it as something more fluid and less rigid than the single hard line conveyed by a cartographer’s pen. To get there will require an era of collaboration and partnership, from government-level climate change panels to grassroots citizen efforts, from design competitions to smartphone apps to gatherings of engineers, city planners, and scientists. It will take people stepping out to meet their neighbors—before the high waters come.

Ultimately, such a collaborative approach could be our generation’s grand act of conciliation with the changing forces of the natural world—one that could represent a cautious step into a future that will allow us to keep some of our coveted seaside haunts while also conceding that some places we’ve set up camp are simply not ours to inhabit.

This essay originally appeared in the March/April 2014 issue of Orion, America’s finest environmental magazine. Request a free trial issue of Orion here.