Courtesy Paul van Hoeydonck/Waddell Gallery*

One crisp March morning in 1969, artist Paul van Hoeydonck was visiting his Manhattan gallery when he stumbled into the middle of a startling conversation. Louise Tolliver Deutschman, the gallery’s director, was making an energetic pitch to Dick Waddell, the owner. “Why don’t we put a sculpture of Paul’s on the moon,” she insisted. Before Waddell could reply, van Hoeydonck inserted himself into the exchange: “Are you completely nuts? How would we even do it?”

Deutschman stood her ground. “I don’t know,” she replied, “but I’ll figure out a way.”

She did.

At 12:18 a.m. Greenwich Mean Time on Aug. 2, 1971, Commander David Scott of Apollo 15 placed a 3 1/2-inch-tall aluminum sculpture onto the dusty surface of a small crater near his parked lunar rover. At that moment the moon transformed from an airless ball of rock into the largest exhibition space in the known universe. Scott regarded the moment as tribute to the heroic astronauts and cosmonauts who had given their lives in the space race. Van Hoeydonck was thrilled that his art was pointing the way to a human destiny beyond Earth and expected that he would soon be “bigger than Picasso.”

In reality, van Hoeydonck’s lunar sculpture, called Fallen Astronaut, inspired not celebration but scandal. Within three years, Waddell’s gallery had gone bankrupt. Scott was hounded by a congressional investigation and left NASA on shaky terms. Van Hoeydonck, accused of profiteering from the public space program, retreated to a modest career in his native Belgium. Now both in their 80s, Scott and van Hoeydonck still see themselves unfairly maligned in blogs and Wikipedia pages—to the extent that Fallen Astronaut is remembered at all.

And yet, the spirit of Fallen Astronaut is more relevant today than ever. Google is promoting a $30 million prize for private adventurers to send robots to the moon in the next few years; companies such as SpaceX and Virgin Galactic are creating a new for-profit infrastructure of human spaceflight; and David Scott is grooming Brown University undergrads to become the next generation of cosmic adventurers.

Governments come and go, public sentiment waxes and wanes, but the dream of reaching to the stars lives on. Fallen Astronaut does, too, hanging eternally 238,000 miles above our heads. Here, for the first time, we tell the full, tangled tale behind one of the smallest yet most extraordinary achievements of the Space Age.

“I was always smitten by space. Even my early work focused on planets, on the Earth and things. I visited New York in 1961, and I ended up in a very good gallery, the Waddell.”

Van Hoeydonck is speaking with us from his home in Wijnegem, in the suburbs of Antwerp, Belgium. “This is my first time on the Skype. I’m sitting in my underwear, and we talk to each other. Very strange.” His leonine face looks hemmed in by the monitor.

Dirk Fret, his secretary and personal assistant, hovers in the background. Van Hoeydonck toasts us with a glass of red wine, and from Manhattan we toast back with two cups of Starbucks Pike Place. “Young people are showing me things I don’t believe—and I’m a man who used to live in the ’60s.”

Van Hoeydonck’s studio, visible in the background, is full of new pieces. The University of Liège is currently hosting an exhibition of his work. This is not a man living in the past, but today, for us, he is making the voyage back.

Courtesy NASA

In 1961—the year President Kennedy declared that America would go to the moon—van Hoeydonck mounted his first space-themed show, in Belgium. Having grown up with a love of Jules Verne and possessing an antipathy toward art academies (“I hated them—they didn’t believe in the real world, they only believed in Antwerp”), he created sculptures inspired by the nascent space program: astronauts in medieval armor (which he called Astros), cybernetic busts, blobby planetscapes, and space babies. Van Hoeydonck’s artist statement for a 1965 exhibit at the Waddell Gallery declared, “The most romantic place on Earth is Cape Kennedy.”

That obsession with space exploration intrigued Deutschman, who had worked in advertising on Madison Avenue before switching to the art world, and who knew a thing or two about ambitious promotional campaigns. Despite van Hoeydonck’s initial incredulity when Deutschman proposed sending an artwork into space, he was easily swayed. Within a month he had begun sketching out concepts for a moon sculpture.

“Louise was a very smart woman, and she deserves the credit for the concept,” van Hoeydonck says. In an unpublished memoir provided by her daughter, Deborah Elliott Deutschman, Louise Deutschman described her conviction that putting art on the moon was not only possible, it was essential. “It was the Space Age … the race to the stars,” she wrote. “I kept on contacting people, and I didn’t stop until we found a way.”

Following up on Deutschman’s leads, van Hoeydonck flew down to Cape Kennedy and booked a room at the Cape Colony Inn in Cocoa Beach (now a La Quinta), which catered heavily to NASA guests, VIPs, and space-obsessed media. He tried various ways to contact the Apollo 15 team but kept running into NASA’s high wall of protection.

The breakthrough came when van Hoeydonck met up with a man he called the Messenger—a former golf pro who had made a full-time hobby of astronaut schmoozing. Everyone in the space world knew the Messenger, and everyone protected his anonymity; articles in Art News and the New York Times, and even official NASA documents, reference him only by his nickname. In our conversations with Roberta Waddell—Dick’s widow, known as Bobby—she outs this mysterious figure as the late Danny Lawler. (David Scott lets loose a “Ha!” when we mention the name to him later: “Danny Lawler, yeah. He was a little guy, nice guy, a PR guy for Lacoste, the T-shirt people, and a space buff. I didn’t have many dealings with him, because he was a bit too promotional for me.”)

Courtesy NASA

The Messenger worked his magic. “At the Cape, I got in touch with the crew of Apollo 15, who had been shown a book about me, and we all agreed to meet at a dinner,” van Hoeydonck recalls. He relives the surreal experience of sitting down to a leisurely meal with the astronauts in a Cocoa Beach restaurant. It was June 2, 1971, just eight weeks before launch. David Scott rose and introduced the others at the table: Jim Irwin, the mission’s Lunar Module pilot; his wife, Mary Ellen; and Irwin’s three children. Meanwhile, neighboring diners gawked. “The astronauts were very famous at the time,” van Hoeydonck deadpans.

Between mouthfuls, van Hoeydonck and Scott discovered shared obsessions with archaeology and Mayan mythology. At the end of the evening, van Hoeydonck praised Scott and Irwin: “ ‘You guys are like the knights that existed in medieval time—the astronauts of the Holy Grail,’ I told them. They toasted me, ‘Look what this guy says! Let’s get him a sculpture on the moon!’ I called my gallery, and whispered, ‘Jesus Christ!’ So quick, I went to Belgium and I put together a little prototype representing the future of man in plaster and plexiglass with my son [artist Patrick van Hoeydonck, who died in 1984], then back to America.”

Surprisingly, van Hoeydonck’s foreign nationality was not an issue. (“The astronauts told me that when they met Nixon later he asked them, ‘The artist—he’s a Democrat?’ They said, ‘No, he’s Belgian,’ and he said, ‘OK.’ ”)

Making art that satisfied both van Hoeydonck’s futurist aesthetic and Scott’s somber philosophical goals proved a delicate process. “I am not an easy man to work with; I like to work alone,” van Hoeydonck confesses. Building on the concept of his Astros, he wanted to evoke the epic journey of the space explorers. (“To our children they are normal; to our grandchildren they will be myth,” he told a UPI reporter at the time.) Scott and his Apollo crewmates were thinking instead about a personal memorial: “We came up with the idea of recognizing the guys who’d died in the pursuit of space,” Scott tells us by phone from his Los Angeles home. “We also wanted to recognize our Soviet colleagues as well”—a remarkable sentiment at the height of the space race.

NASA regulations for what could be brought into the Lunar Module imposed their own constraints. Then there was the matter of fabricating a sculpture tough enough to survive on the moon, where daytime temperatures can hit about 250 degrees Fahrenheit and nights swing to about 250 below zero. Van Hoeydonck approached Milgo/Bufkin, a Brooklyn-based foundry that started out making horse carriages but had evolved into a leading fabricator of metalwork for artists, to solve the dual aesthetic and technical challenge.

“The sculpture had to be small, and I was told by Scott that it was not allowed to be any race—not black, not red—not male, not female, and able to resist extreme cold and hot. So I had to design a thing like that,” van Hoeydonck says. The retro-futurist and spiritual overtones of his other sculptures mostly got weeded out in the process. “I’ve done better. It is not the best van Hoeydonck.”

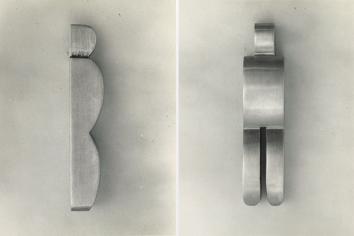

Bruce Gitlin, the 70-year-old head of Milgo/Bufkin, shared his memories of how Fallen Astronaut was made. His office is full of models and photos of the famous works he has fabricated—everything from Robert Indiana’s LOVE sculpture in midtown Manhattan to the signature, mirrored-steel windows and walls in the destroyed lobbies of the World Trade Center’s twin towers. “Paul would come over, we’d go to Katz’s and get pastrami and corned beef on rye,” Gitlin said while gesturing expressively. “When we started talking about making a sculpture, he had a melted, globular, humanoidist form. He said, ‘Could you make this into a more human form, but still semi-abstract?’ It was very quick from his model to my reality. The prototype and the final piece on the moon were carved from aluminum, hand-fabricated by me, because I knew if it was traveling to the moon it had to be light.”

Courtesy Waddell Gallery*

Van Hoeydonck wanted his aluminum figurine to stand erect, gazing up at the sky. During our second Skype call, he asks his secretary to show us a prototype of that version of Fallen Astronaut. Dirk Fret pulls it from a storage drawer. It looks like a slightly fatter cousin of the final version, but embedded in an acrylic cylinder. The cylinder both defines the space around the moon man, and ensures that he would remain upright.

Bobby Waddell has copies of two other Fallen Astronaut prototypes stored in her Upper West Side apartment. She plops them down on her dining room table during our lunch visit. One is embedded in acrylic, a doppelgänger of the one shown to us by Dirk Fret; the other is naked metal. We pick them up gingerly. There is a lot of space history sitting there next to the turkey burgers. The encased version, marked “artists proof 11,” has the heft of a full can of Coke and a similar form, though slightly taller and narrower. By comparison, the bare aluminum piece feels remarkably light and fits easily into the palm.

In the end, the simple, naked version got the nod.

In 1971 David Scott was literally on top of the world. Five years earlier he had flown 6 3/4 loops around the planet aboard Gemini 8. He was the Command Module pilot for Apollo 9, a pathfinder mission that tested many of the procedures used to place Neil Armstrong on the lunar surface. Based on Scott’s experience and sterling flight record, NASA selected him to command Apollo 15, the fourth moon landing.

When we talk to Scott, now 81, his voice is unexpectedly youthful, and he is still recognizably the heroic spaceman who gave key interviews to Tom Wolfe for The Right Stuff. Scott’s cadence slows as he winds his memory back to Fallen Astronaut.

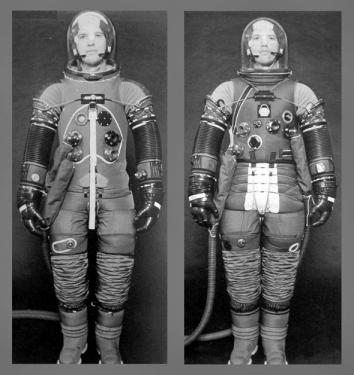

Getting van Hoeydonck’s moon man packed and ready for flight was one of a thousand last-minute tasks Scott needed to complete ahead of Apollo 15’s July 26 liftoff. “Several days before launch, we had what they called ‘fit and functional.’ Everything we were going to use on the moon or on the flight was laid out on the table, and we inspected every item to make sure it fit and functioned the way we expected it to. The flight crew support team put all this stuff together—the personal preference kits [small bags for personal effects] and cameras and tongs and this and that.

“We started out in the morning in our birthday suits, and then somebody took care of everything for us, handling the equipment, everything from spacesuits to food, film, towels. The doctors took their peek, too, to make sure the birthday suit is in working order. The flight crew support team made sure everything on board was properly organized, stowed in a sequence that you’d use it, nonflammable, vacuum-packed—safety first. Then we had suit techs to suit us up. People took care of you all the way out to the pad. Things were stowed in the spacecraft before launch date, because on launch date you get in and you go.

“How the little sculpture fit in with those procedures I probably would never be able to remember. I just know it was in my pocket when I got to the moon.”

Courtesy NASA

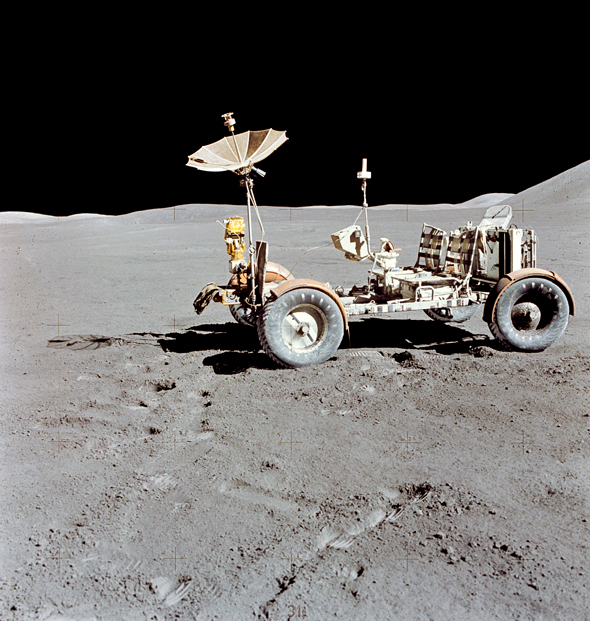

On July 30, 1971, the Lunar Module touched down on moon’s Hadley-Apennine region, between a meandering gulley and a range of steep mountains. With Al Worden orbiting overhead, Scott and Irwin spent three days on the surface. During that time, Scott toured around in the never-before-used lunar rover; he describes himself as “the first licensed driver on the moon.”

“You never have enough time on the moon,” Scott says. “People don’t realize how much longer it takes on the moon to do things that you practice on the Earth. Nobody knows why. Perhaps we were more careful up there. And then you have to get ready to lift off because the rover is coming to pick you up—and you don’t want to miss the train.”

His time on the surface was nearly finished before Scott managed to squeeze in a brief Fallen Astronaut ceremony. “I was going to drive the rover out, set up a TV camera to watch the liftoff, put down the little astronaut and the plaque, and take a photo,” he says. “On Apollo 15 we took over 1,100 photos on the surface of the moon, and all those are without any rangefinder or light meter. So that was another part of setting up the Fallen Astronaut: making sure I got a good photo of it, because nobody knew about it.”

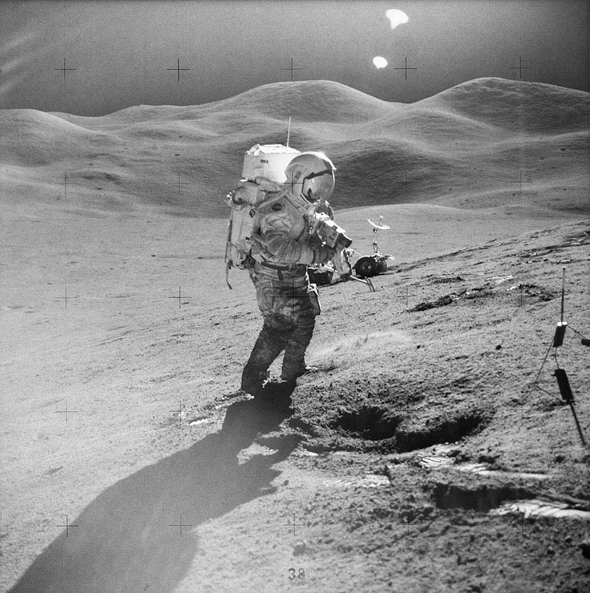

Finally Scott found his moment, and he wanted to keep it private. Irwin distracted Mission Control in Houston with inane chatter while Scott took a few bounding steps north from the lunar rover and made Fallen Astronaut a citizen of the moon.

Courtesy NASA

He pulled Fallen Astronaut from his oversize pocket, placed it directly on the moon dust, and nestled the memorial plaque next to it. A spiritual man who keeps his faith private, Scott treated the dedication of Fallen Astronaut as a wordless funeral service. And a short one. “There was a big checklist to take care of first,” he says. “We had to stow all the rock samples and the cell samples, and there’s a lot of procedures you have to go through before you get in and close the hatch for the last time. So it was a brief moment, then Jim [Irwin] said, ‘C’mon, Dave, get back; we gotta load up.’ ”

Inside the Lunar Module, after he had taken his helmet off, a distinctive odor hit Scott’s nose: spicy, a bit like gunpowder—the smell of moon rocks. Five hours after the Fallen Astronaut moment, the Lunar Module took off and the moon slipped away.

Can he still conjure up the moment when he placed the first piece of art on the moon? “Of course I recall what it felt like placing the plaque and artwork there,” he replies almost before we finish the question. “Eight of my friends were being recognized, like Charlie Bassett [who died in a plane crash while training for Gemini 9]. Recognizing Fallen Astronaut as a piece of art is a nice thing, but don’t forget why we did that.”

The forgetting began almost immediately after Apollo 15 returned to Earth. David Scott publicly mentioned Fallen Astronaut just once, at the big post-mission NASA press conference a week later, on Aug. 12, 1971. “It kind of receded in the background. We did what we felt like we should do. We had no intention to make a big deal out of it other than to know that we did it,” Scott tells us.

Courtesy NASA

Scott and his crewmates had more pressing business—cranking away on the NASA publicity machine, the routine after each Apollo landing. “We went on State Department tours, and we went around the country to schools and hospitals and that sort of thing. It was a busy time.” One stop: 1600 Pennsylvania Ave. “Nixon invited the three of us on Apollo 15 along with all the kids” in their families, Scott says. “After dinner, he led them on an extensive tour of the White House like the Pied Piper. They just ate him up.”

Van Hoeydonck returned to his work in peculiar silence. His dream of leading humanity to the stars looked increasingly fantastical. At the press conference, Scott had not named the sculptor who created Fallen Astronaut. Nor did the official NASA press release that followed. Scott preferred to keep it that way—treating Fallen Astronaut as an anonymous memorial—and thought he and van Hoeydonck had an understanding to that effect. “Paul had agreed, as we all had, that he would remain unknown,” Scott says with even certainty.

Van Hoeydonck initially played along, though he had a starkly different impression of the project. Two days after the NASA press conference, van Hoeydonck wrote to the Apollo 15 crew: “To open the way to the Stars is the most important mission of man in this century.” In a separate letter, sent directly to Scott the same day, he added, “Sorry you didn’t find an ancient temple but … the experience of walking on the moon must be out of our dimensions.”

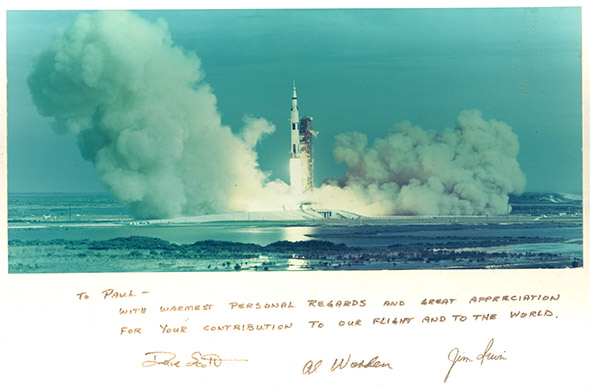

Courtesy Paul van Hoeydonck/NASA*

As the days went by, van Hoeydonck grew agitated that he was unable to take credit for what he considered his most historic creation. The disagreement came out into the open on Sept. 21, while the Apollo 15 astronauts were in Belgium for a space conference. “I had breakfast with the astronauts in Brussels,” van Hoeydonck recalls. “Then Dave Scott says, ‘You have to wait one year before you say anything to anyone about the sculpture.’ ” The artist was only somewhat mollified by kind words from the crew, including an autographed photo of the Apollo 15 launch that expressed “great appreciation for your contribution to our flight and to the world.”

Van Hoeydonck was also dismayed by the name “Fallen Astronaut,” which did not make the sculpture sound at all like a gateway to the stars. “It was the astronauts’ idea, without my consent, to call it the fallen astronaut,” van Hoeydonck later wrote to his New York lawyer, Harry Torczyner. “After my return from the States … three Russian cosmonauts [on Soyuz 11] died on their return to Earth. And after that, the astronauts called the sculpture the fallen astronaut.” He still talks about the decision with a tinge of anger. “The astronauts said, ‘It is a dead astronaut, a fallen astronaut.’ ”

“I don’t know where that name came from,” Scott says. “We might have said it, all those years ago,” Scott says. “But the important thing to remember is that it’s a memorial—the figurine and the plaque together—that’s what it is.”

Courtesy NASA

Those slights were weighing on van Hoeydonck when, a few months later, he came across a NASA booklet called Apollo 15: At Hadley Base and flipped to the passage about Fallen Astronaut. “Not my name mentioned. Nothing,” he says, voice rising. As we look at the booklet now, it seems plausible that the relevant text was mindlessly lifted from the similarly truncated information in the NASA press release. But von Hoeydonck interpreted the omission as a deliberate slight engineered by Scott. “Now I understood: I wait one year and his story is finished, he is the man who put the sculpture on the moon.”

The rift between astronaut and artist widened further on Nov. 29, when van Hoeydonck opened his mail to find a note from the crew of Apollo 15: “We have been contacted by the Smithsonian Institution requesting permission to put on permanent display an exact replica of the memoriam we left at Hadley Base on the moon. We discussed it, and thought it a good idea if you agree. They, of course, want an exact replica of the Fallen Astronaut/Cosmonaut which they define as ‘made to the same dimensions, material, finish and appearance by the same workman.’ They are quite willing to purchase the figurine if you are willing to make two more.”

Scott was encouraged by the Smithsonian’s interest. “I talked it over with Jim and Al and we said, Smithsonian, that’s high-quality, we’ll do that.”

Van Hoeydonck, on the other hand, was doubly insulted. First, that the Smithsonian Institution had to contact the astronauts because the artist’s name was secret; and second, that the letter of invitation referred to him as a “workman.” It didn’t matter that the astronauts were repeating the word that had been used by the Smithsonian. Forty-two years later, van Hoeydonck is still stewing: “That astronaut called me a ‘workman,’ and said to be good and stay quiet. I’m not a workman; I’m an artist. I said, ‘If you are proud to have been on the moon, I’m proud to have a sculpture on the moon. I am the man who made that sculpture, damn it.’ ” In a later conversation, van Hoeydonck tells us that if he was the “workman” behind Fallen Astronaut, then Scott was just “the postman.”

In the end, posterity trumped pride. Van Hoeydonck produced two replicas of Fallen Astronaut for the Smithsonian. One of those figurines became part of the permanent collection of the National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C. The artist later presented the other to the king of Belgium. Separately, Scott had a reproduction of the memorial plaque made by the same Houston firm that crafted the original.

The Smithsonian’s request for the replica convinced van Hoeydonck that it was time to go public. Dick Waddell and Deutschman agreed and worked their contacts at CBS News. “We arranged that, at the time of the next flight to the moon [Apollo 16], CBS would announce, via Walter Cronkite, that I was the man who made the sculpture on the moon,” van Hoeydonck says.

On March 9, 1972, van Hoeydonck alerted Scott that he would be on TV to “announce that Man has put the first work of art on the Moon.” Scott responded on March 20: “There will probably be questions relative to the purpose of the figurine, some of which only those of us in the crew can answer meaningfully. … We hope to avoid any promotion of publicity on something we feel has already reached the peak of its meaning.”

On March 25, van Hoeydonck delivered his final word, in a handwritten note: “The only purpose [of going on CBS] is the announcement that I am the artist who designed and created the sculpture, which you will agree is only natural. An artist is allowed to be known as the maker of his own work. I kept silent, but as I am the only artist whose work is known to be totally devoted to space, more and more talking has been going around in the art world. … I do understand completely your message and believe me it is not in the least in my intention to degrade the memorial. P.S. Typewriter is broken, Please excuse me the writing.”

Courtesy Paul van Hoeydonck/Waddell Gallery*

Today, Scott is audibly rankled when he remembers van Hoeydonck’s decision. “Anonymity was part of what we wanted to do. We didn’t want any falderal or fanfare or commercialization—we just wanted to recognize our colleagues in a somewhat formal, quiet, peaceful environment on the moon. When we got back, we announced what we’d done because we thought it was appropriate to recognize our colleagues. That’s all.”

Walter Cronkite’s broadcast took place at 12:30 p.m. EST on April 16, 1972, the day of the Apollo 16 launch. “In the VIP area, there’s Jordan’s King Hussein and the two Nixon girls, Vice President Agnew, the Russian poet Yevgeny Yevtushenko and the Belgian sculptor Paul van Hoeydonck, the only artist with work on the moon,” Cronkite began. Van Hoeydonck, clutching a Fallen Astronaut replica and sporting a white jacket and tie, explained his motivation in creating the sculpture: “I thought of the future of man, that the only possible future of man was in the stars.” He started to describe Fallen Astronaut as the “smallest memorial on Earth.” Cronkite cut him off: “—not on Earth, though. Smallest memorial in the universe. And there it is. That’s the way they left it.”

With van Hoeydonck formally linked to Fallen Astronaut, his optimism returned: Now surely he would have a prominent forum for his futuristic Astros and other types of sculptures he called Mutants and Robots. Two weeks after the Cronkite interview, The New Yorker quoted van Hoeydonck at length about his moon sculpture. “Amid all the debris of technology left in space, it is the only sign of man’s arts,” he said. “My Homo sapiens, my cybernetic man, has in whole or part come true. I am optimistic about mankind. I think the future of man is out there. In twenty years, I think we’ll be off to other solar systems.”

Van Hoeydonck’s dreamy visions didn’t last long. “People hated the Fallen Astronaut,” he says, still baffled 40 years later. “They did not like that we were on the moon with that sculpture.” Bobby Waddell believes the New York art world resented van Hoeydonck as an outsider, a foreign artist represented by a wealthy but second-tier gallery, who did not deserve to have the moon all to himself. Writing in the April 22, 1972, edition of the New York Times, influential art critic Grace Glueck sniffed that the moon sculpture “resembles nothing so much as a swollen tuning fork.”

Courtesy NASA

Within the government, enthusiasm for space exploration was ebbing. The planned Apollo 18, 19, and 20 moon landings had already been scrubbed in 1970, and Saturn V rockets were left moldering in their hangars. President Nixon had considered canceling Apollo 16 and 17 as well, which would have left David Scott and James Irwin as the last astronauts to walk on the moon. Those missions were saved only by the intervention of Caspar Weinberger, Nixon’s budget director, who argued in a private memo dated Aug. 12, 1971—the very day of the Apollo 15 press conference announcing Fallen Astronaut—that the cuts “would have a very bad effect, coming so soon after Apollo 15’s triumph.”

To improve the wobbling fortunes of both his gallery and his artist, Dick Waddell made a fateful decision. With van Hoeydonck’s consent, he drew up plans to offer a signed series of 950 Fallen Astronaut replicas to collectors at $750 each, with an eye at creating a second, cheaper series. The gallery once again contacted Bruce Gitlin at Milgo/Bufkin about making the copies and drew up a full-page ad for the July 1972 issue of Art in America, boasting, “Each is similar in the most exact detail to the sculpture on the Moon.”

Van Hoeydonck knew the Apollo 15 crew would be displeased, but he was in no mood to hold back. In a 1972 interview in the New York Times Waddell explained: “Van Hoeydonck was really in a rage. … At this point we decided, to hell with Scott. This is a capitalist country. If we can make money on this, why not?”

On May 9, 1972, Scott wrote to van Hoeydonck, alarmed. “I have heard the Waddell Gallery intends to produce a number of replicas of our fallen astronaut and sell them. It is difficult to believe they would do that, and I doubt if they could do it without permission of the artist. … As I expect, this is probably an unfounded rumor, but I would appreciate any light you can shed on the subject.”

Van Hoeydonck responded with a fervent, 1,500-word letter. In part he sought to convey the difficulty of his situation. “The press is not at all wild about [Fallen Astronaut], spacetravelling being out, no blood nor violence being involved, and public opinion turned completely anti, they still wonder why ‘something other than hardware has been put on the moon’ (their general saying). … I’m selling my work with even more difficulty than before, collectors and critics not knowing what to think about an artist represented on two planets. People’s reactions are very strange, also envy is playing a big part in it.” Ultimately, he wrote, “I believe that we have no right of holding this image, which can help space, confined to the moon, the Smithsonian, the Belgian King, and ourselves.”

Forty years later, Scott remains unmoved. “Disappointing,” he says. “The arrangement was to make one copy and let us do our thing, and then it’s history. I’m from Texas, and in Texas a deal’s a deal.”

The dispute between Scott and van Hoeydonck might have remained a private argument over the nature of art and human destiny in space, but larger forces were at work. By this time Scott and his crewmates were in hot water over what came to be known as “the postage stamp incident.”

During Apollo 15 the three astronauts had brought 641 postal covers (stamped envelopes) to the moon, to be returned with a lunar postmark. Some were authorized by NASA as souvenirs, but 100 of them were earmarked for a German collector named Hermann Sieger. The plan was that he would buy them for $21,000, split three ways to create trust funds for the astronauts’ children, and hold off on reselling them until after the astronauts were out of public life.

Contrary to the plan, Sieger began selling the postal covers almost immediately. The Apollo 15 crew quickly backed out of the deal, but word of the sale was already getting around. Deke Slayton, NASA’s director of flight crew operations, caught wind of the sales and scolded Scott, Worden, and Irwin for bad judgment. Astronauts were not supposed to cash in on their missions. Slayton felt compelled to inform his superiors. NASA officially reprimanded the crew and launched an internal investigation. On Aug. 3, 1972, Scott and his teammates were called before a closed, five-hour Senate hearing, chaired by Clinton P. Anderson of New Mexico, to explain their actions and to submit to Congress’s favorite form of punishment: the ritual humiliation.

Courtesy NASA

The postage stamp incident was unrelated to the reproductions of Fallen Astronaut, and yet intimately tied to it. NASA officials had just finished dealing with a controversy in which the Apollo 14 crew had carried silver medals produced commercially by the Franklin Mint. Now an artist appeared to be profiteering from another Apollo mission. In his book Falling to Earth, Al Worden recalls the Senate committee’s view that Fallen Astronaut “was just another example of a lengthening list of commercial deals that involved Apollo flights.” There were also intimations that Fallen Astronaut was smuggled to the moon; NASA Administrator James Fletcher had to issue a statement that Scott had discussed the memorial with top NASA officials “and they thought it would be a fine gesture.”

“Everybody carried [stamp] covers, so that wasn’t anything unusual,” Scott tells us. “The Apollo 15 covers got sold by a guy in Germany, the public affairs office got confused and didn’t tell Congress before they told the press, the guy in Germany panicked—so that was the end of the game.” He is technically correct. Other Apollo crews carried stamp covers and other mementos, or made money by selling their stories to Life magazine. But this time the mood of the country was very different.

As the economy sagged and public fascination with the moon race waned, NASA’s budget got sliced up and reapportioned. From 1970 to 1972, the agency’s funding declined 20 percent in real dollars. Over the next two years, it dropped an additional 24 percent. NASA was no longer untouchable, and neither were its emissaries.

On Sept. 19, 1972, while the rest of the country was fixated on the daily Watergate revelations, two NASA inspectors, Glenn McAvoy and R.E. Wood, flew to Antwerp to interrogate van Hoeydonck about Fallen Astronaut. After stopping for lunch, the officials rang him up from a payphone in a downtown Chinese restaurant, full of sharp questions. Who created the sculpture, who reproduced it, and who profited from those copies? Did any private parties earn money off an official U.S. government program?

Two days later van Hoeydonck met with the inspectors in a local law office. “The interview lasted almost two hours. They asked me if the astronauts were receiving a share of the eventual money resulting from the sales of the Fallen Astronaut, I answered defiantly not,” van Hoeydonck wrote to his lawyer, Harry Torczyner, adviser to art stars such as René Magritte.

Bruce Gitlin of Milgo/Bufkin recalls a series of stranger and more enigmatic encounters with government agents. After working on a small initial batch of Fallen Astronaut replicas, “I got a call from someone at NASA who said that I better cease and desist from any other work on the moon man project,” he says. “I asked, ‘Why?’ They said, ‘Because we're telling you so.’ It was like, ‘If you don’t do it, you're going to be in trouble with the government.’ ”

Waddell and van Hoeydonck had Gitlin make only 50 copies of Fallen Astronaut before pulling the plug.

The immediate legacy of Fallen Astronaut, like that of the end of the Apollo program, was dispiriting. The planned series of replicas spawned a wave of negative publicity for both gallery and artist. A typical story, from the New York Times, calls the series “commercial exploitation of the nation’s flights to the moon.” Two days after the Walter Cronkite interview, Dennis A. Miller—a Toronto-based filmmaker who was staying with the Waddells—had started shooting a documentary about van Hoeydonck, called Space Child. The 56-minute final cut never even got a proper screening. “There was a preview and garden party in a countess’s villa in Italy, but other than that nobody has seen it,” says Bobby Waddell.

Meanwhile, business declined at the Waddell Gallery. Dick Waddell fell into a depression, divorced Bobby, and died in 1974 at age 50. Van Hoeydonck pressed on steadily with his art, but largely retreated from the United States.

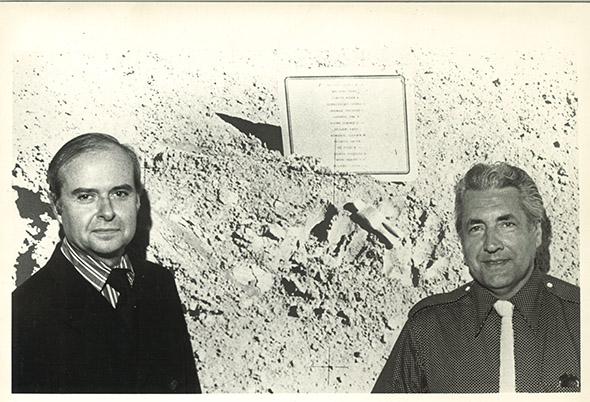

Photo courtesy Robert Otter/Waddell Gallery

Scott and his Apollo 15 teammates never flew again—although as Scott drily notes, there weren’t a lot of places to fly to after Apollo. Worden worked on various technology ventures, including a partnership with the former head of General Motors. Irwin started a ministry, the High Flight Foundation, and searched for Noah’s Ark on Mount Ararat in Turkey before his death in 1991. “He didn’t go off the deep end,” Scott says in reaction to our inevitable question. “He had a belief; lots of people have beliefs.” Scott resigned from the Air Force in 1975 and left NASA two years later.

Only after the post-Apollo hangover had subsided did NASA reconsider its position regarding the postage stamp incident. A 1978 investigation by the Attorney General’s Office largely exonerated Scott, Worden, and Irwin. Five years later, NASA returned the stamp covers to the astronauts, effectively rescinding the accusations. (Worden, now living in Vero Beach, Fla., sells space memorabilia at alworden.com.) We ask Scott whether he is ever tempted to set the record straight about the stamps and the sculpture. He replies that he already had his say in his book Two Sides of the Moon, though he’s vexed by lingering inaccuracies in the Wikipedia entry about the incidents. We ask: Why didn’t he get a friend to log in and correct the entries? He responds with a startled pause. “Is that right? I didn't know you could do that!”

Photo courtesy Jawed Karim/Creative Commons

After Apollo, crooks apparently paid more attention to Fallen Astronaut than historians did. Bruce Gitlin reports on a bootleg copy that came to van Hoeydonck’s attention: “A man called him up and asked him to authenticate a sculpture of Fallen Astronaut in silver. Paul called the police and said, ‘There’s a forgery here.’ Paul told me that there was another forgery, made in gold, that was sold to the Shah of Iran.” Bobby Waddell recalls that the head of Parmalat, the packaged long-life milk company, called her to see whether he could buy one of the official copies. “I told him it was never going to be sold,” she says.

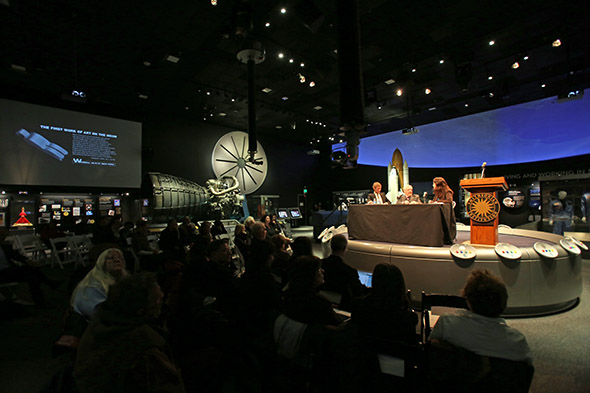

Now, after years of obscurity, Fallen Astronaut is making an unexpected comeback. Four decades after van Hoeydonck’s private meeting with the Smithsonian’s director, the Smithsonian invited the artist and his most famous sculpture out into the public for an absurdly belated lecture on Dec. 12 at the National Air and Space Museum.

Even this event has proved star-crossed. When we contact Scott to see whether he will attend, we are surprised to learn he wasn’t invited. He is too. “Surprised! You bet. And disappointed, and frustrated.” He sighs. “It’s like, gee-whiz, guys, maybe we should all talk about this before it happens.”

We inquired with Margaret Weitekamp, curator of the museum’s Social and Cultural Dimensions of Spaceflight Collection, and shortly afterward she asked Scott whether he would participate in a video greeting. He declined. “Normally when we invite an astronaut, we fly him in, put him up in a hotel,” she tells us. “It’s embarrassing, but with budget cuts, we just didn’t have the money to do this in normal style.”

We press Scott on why he won’t attend the event: Isn’t he curious to see van Hoeydonck, to scrape away years of ill will? “I never really had any desire to meet up with him again, to tell you the truth,” Scott replies, calm but definitive.

Van Hoeydonck is in a more nostalgic frame of mind as he anticipates the event. He wells up briefly on our computer screen over Skype. “I don’t like the story not being told truthfully. I don’t exist in history. I am the only human being who has been able to get a sculpture to the moon. Nobody can take that away from me.”

The day before the Smithsonian lecture, we take a road trip to Washington, D.C., with Bobby Waddell piloting her Honda CR-V and Deborah Elliott Deutschman navigating. That evening we meet van Hoeydonck at Ristorante Piccolo, a trattoria in Georgetown. It is one day into his first visit to the United States in 15 years. He arrives in high spirits, wearing a stylish shirt and colorful graphic tie and wrapped in a thick fur coat; he is accompanied by his secretary, his new young girlfriend, and five close friends from Antwerp.

Van Hoeydonck orders the frutti di maré, and his comments seemingly pick up where he left off in his historic restaurant meeting with the Apollo 15 crew in 1971. The next day he will have a personal meeting with Charles Bolden, the NASA administrator, van Hoeydonck tells us. Tonight he waxes philosophical about space exploration and the future of humanity. “At some point machines will take over, we will not be necessary,” he says. “They are already making robots that have ‘sentiment.’ We will have to go somewhere else and start over. We will be like Adam and Eve.”

At 1 p.m. the next afternoon, van Hoeydonck climbs a dais to face the assembled crowd in the Air and Space Museum’s new Moving Beyond Earth gallery. The turnout is about 40, including ourselves, the artist’s entourage, and the Belgian ambassador. Introductory comments by the Smithsonian’s art historian place Fallen Astronaut in the context of other space-themed creations by Andy Warhol, Annie Leibovitz, and Norman Rockwell, all of which sit side by side with works by van Hoeydonck (including the replica of the moon man) in the collections of NASA and the Smithsonian. But only one of those artists is exhibited on another world.

Van Hoeydonck retells the origin story of Fallen Astronaut with a mix of pride and hurt. He is still upset at having to remain quiet after Apollo 15. He is still astonished at what he has achieved. “I would never go into space myself—I am a coward. I have great admiration for the astronauts who go there,” he says.

Photo courtesy Donald Woodrow

If Fallen Astronaut is emblematic of lost glory to van Hoeydonck, to Scott it holds a glimmer of future hope: the promise that the hard work and sacrifice that took humans to the moon could again drive our species on to new explorations. “The NASA of the 1960s is gone. It’s finished,” Scott says. But with a jet pilot’s determination, Scott is thinking in concrete terms about how to rebuild. “I work with students, mostly seniors, grad students. What we teach them they will apply in 20 years. Science-engineering synergism. If we can get the young people stimulated, motivated, and educated, somewhere down the line we can get things moving again.”

China has just landed a rover on the moon, which will go for humanity’s first drive on the lunar surface since Apollo 17. India’s first deep-space probe is en route to Mars, scheduled to arrive next September. Then there are the commercial ventures: SpaceX, Virgin Galactic, and the like. Maybe the United States government will not be the one to “get things moving again.” But whoever takes that next giant leap, Fallen Astronaut will be waiting, unchanged, eternally patient, as only a cosmic emissary can be.

*Correction, Dec. 17, 2013: This post originally misattributed to Laurie Gwen Shapiro a photo courtesy of Paul van Hoeydonck and the Waddell Gallery. A photo courtesy of the Waddell Gallery was misattributed to Shapiro, Corey Powell, and NASA. A photo courtesy of van Hoeydonck and NASA was misattributed to Shapiro and Powell. A photo courtesy of van Hoeydonck and the Waddell Gallery was misattributed to the Waddell Gallery alone. And a photo misidentified David Scott as James Irwin.