Fresh Thinking

John Harrison was a dairyman who looked at the dairy industry with a unique perspective.

Harrison grew up on his family’s dairy farm, learning the tricks of the trade. Not long after his college graduation, he set out on his own and purchased land that would become the foundation of Sweetwater Valley Farm's 1,800 acres in Philadelphia, Tenn.

For Harrison, running a successful dairy operation meant viewing the farm as a long-term business that demanded fresh thinking. By 1998, he had a plan to begin on-farm production of cheese. He was the only dairyman in his area to make such a bold move and was told more than once that his farmstead cheese would struggle to get shelf space in the stores.

"I had to work hard to do things that would put me ahead of everyone else," Harrison explained. "I can't worry things I can't control like the weather. I just have to stick it out."

It's this get-it-done attitude that has allowed Sweetwater Valley Farm to flourish despite the challenges that come with being a farmer.

Innovation has long been a core value at Sweetwater Valley. Like most dairy farmers, Harrison starts his work day at around 5 a.m. and doesn't stop until the cows, literally, come home.

Harrison also is a cheese-maker—an integral part of his farm business. In fact, of the 20 million pounds of milk produced annually on the farm, roughly 10 percent is used to make cheese.

But, as is the case of most innovation, there are risks.

When Harrison began on-farm cheese production in 1998 he was the only dairyman in his area making such a bold move and was told more than once that his farmstead cheese wouldn't get shelf space in the stores because it wasn't organic.

But by early 2000, Harrison found that consumers craved unique, local products. Support poured in, and Sweetwater Valley Farm attracted travelers looking for local flavor. Now, more than a decade and 25 varieties of Cheddar later, the farm is renowned for its artisanal cheeses. The farm produces about 200,000 pounds of cheese each year. Still, cheese is only one part of the farm's equation. Harrison hasn’t lost sight of the basics that are important to all dairy farmers – his land and his cows. Sweetwater is home to about 1,300 cows and 20% of their milk is used to make cheese while the rest is sent off the farm to be packaged for consumers. Harrison is also committed to help bridge the gap for what he sees as a growing disconnect between consumers and his farm.

“Most dairy farmers have strong roots in agriculture and feel very connected to agriculture. But, for the vast majority of people, they feel very removed from it," said Harrison. "Most kids don't get to see where food comes from or get to see a calf being born."

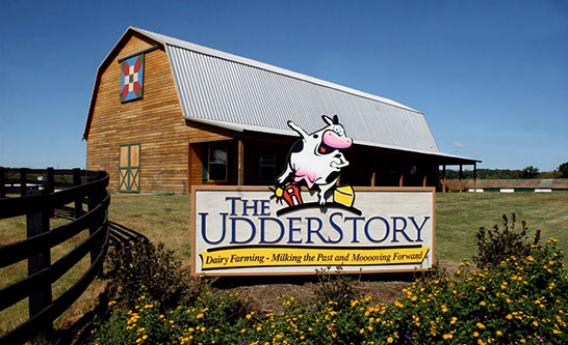

Harrison looked at his farm and cheese-making business as an ideal educational opportunity and addressed the issue by installing “The Udder Story,” a 5,000-square-foot exhibit and event center that offers an educational farm excursion. Visitors can see how feed is grown, how farmers previously milked cows by hand and how technology has improved efficiencies. Sweetwater Valley has welcomed more than 80,000 visitors since its opening in 2010 and the farm also offers tours of the barn, the milking parlor and the maternity and calf care center. Visitors also get a look at the farm's innovative features, including a sustainable waste-management system that allows Harrison to reduce his use of commercial fertilizer from 60 percent to 10 percent by replacing fertilizer with cow manure. It's a move that not only cuts fertilizer costs but gives the farm a much greener footprint. In addition, Harrison's land grows 80 percent of the food consumed by his cows.

“I always wanted to be more diversified and felt that you need to grow a good portion of what you're consuming,” Harrison said.

While Harrison continues to focus on his farm's success, his cows are busy feeding the world. An average dairy cow produces about 15,000 gallons of milk in her lifetime.

"You have to think about how many people she can feed, and she doesn't even compete with humans for what she's eating," said Harrison. "I can do my share in feeding people, and also do my share in making things different and interesting for consumers with our cheeses.”

Harrison may have the beginnings of his own tradition --two of his five children have already expressed interest in returning to work on the family farm after college. Harrison says he feels optimistic about the dairy business, adding “it helps having children who want to come back to it.”