A Death in Yellowstone

On the trail of a killer grizzly bear.

Photograph by James Yule.

On Friday a hiker was found dead in Yellowstone National Park. CNN reports that based on a preliminary invesitgation, "an adult female grizzly and at least one cub were present" at the hiker's death, and that, if found, bears involved in human fatalities are generally euthanized. In 2012, Jessica Grose wrote about death in Yellowstone. Her story is reprinted below.

Also see our Magnum Photos gallery on bears.

A grizzly was ambling along the Yellowstone River on a clear day in late September 2011, when she lifted her nose up and smelled something familiar in the air. She couldn’t tell quite what it was, but it smelled like food. Maybe the shredded remains of a bison taken down by a wolf pack, its innards sloughing out of its stomach and onto the riverbank. The sow may have spent the day digging up pocket gophers, but a feast like this would really help her to pack on weight. Within eight weeks she'd be taking her two young cubs into a den in the side of a slope for the long Western winter. They needed fat, and soon.

After months of a diet consisting mostly of grass and nuts and roots, the scent of dead meat was impossible to resist. The mother grizzly walked in the direction of the carrion with her cubs scrambling along behind her. The bigger one, with the blond face, was probably closer on his mother’s heels, with his brother, the color of burnt sienna, lagging behind. The sow had to keep a close eye on her offspring. There was always the threat of male bears trying to kill her family. They knew she wouldn’t go into heat again as long as her cubs were with her.

Finally they located the source of the delicious smell—a wheeled, 10-foot-long aluminum tunnel, open on one end, that had been deposited near the river just south of a campground. The mother bear stuck her snout in the tunnel and then climbed in toward the meat. It was roadkill, probably elk or bison. When she touched the bait, a trapdoor dropped behind her.

She spent a long, desperate evening in that trap. Her two cubs stayed close by, but she could only watch them and smell their scent through the ventilation holes at the front and back ends of the tube. At first she might have been agitated, clawing against the smooth metal insides of the trap. But as the hours slipped by, she may have settled into her prison, resigned to her fate.

After daybreak, she heard a whap-whap-whap sound, like the heavy beating of wings, and then different strange noises from outside the tunnel. As she saw people approaching, she began to get angry. Her cubs backed off at the first sight of the humans, but they returned just minutes later when they smelled more dead meat: Both were soon coerced into another barrel-shaped piece of metal. Once all three animals had been captured, the tubes were wheeled onto a helicopter and flown several miles away, to another part of Yellowstone National Park. That’s where everything went black.

While the mother bear was sedated, government biologists pulled hairs from her body, and took a vial of blood from her wrist. Then they trucked her to a large area at Yellowstone Headquarters known as the “bear room,” and kept her there in the tube for three days, fed and cared for by Yellowstone staff. Her cubs were being held in the bear room, too, but she couldn’t touch them, couldn’t cuff them affectionately with the back of her paw if they were misbehaving.

On the morning of Oct. 2, 2011—the sow’s fourth day in captivity—the bear management team at Yellowstone did something they absolutely hate to do. Kerry Gunther, the head bear manager at Yellowstone, stopped by the headquarters with his wife. It was his 53rd birthday, and he wanted the company for the grim task he faced.

His wife was keeping notes when Gunther and his technician injected the bear with a dose of Telazol, a larger helping of the same sedative they had used earlier to take the blood sample. Then one of them shot a captive deadbolt—the kind used in industrial slaughterhouses—directly into the animal's brain.

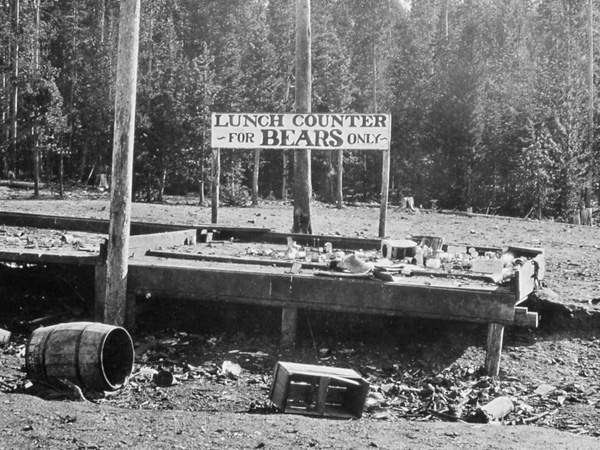

Courtesy of the Grizzly and Wolf Discovery Center.

It took a couple of minutes for the mother grizzly to stop breathing, and for her heart to stop beating. For her cubs, this marked the end of their life of freedom. Eventually, they would be shipped off to the Grizzly & Wolf Discovery Center, a tourist attraction in West Yellowstone, Mont., where they will spend the rest of their lives.

The euthanization of the bear known as “the Wapiti sow” was the culmination of a series of horrifying events that had gripped Yellowstone for months, and alarmed rangers, visitors, and the conservation biologists tasked with keeping grizzly bears safe. In separate incidents in July and August, grizzlies had killed hikers in Yellowstone, prompting a months-long investigation replete with crime scene reconstructions and DNA analysis, and a furious race to capture the prime suspect. The execution of the Wapiti sow opens a window on a special criminal justice system designed to protect endangered bears and the humans who share their land. It also demonstrates the difficulty of judging animals for crimes against us. The government bear biologists who enforce grizzly law and order grapple with the impossibility of the task every day. In the most painful cases, the people who protect these sublime, endangered animals must also put them to death.

* * *

Photograph for Slate by Jessica Grose.

Whenever a grizzly bear commits a crime in the continental United States, Chris Servheen gets a call at his office at the University of Montana in Missoula. Servheen has been the Grizzly Bear Recovery Coordinator for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service for three decades, and his phone usually rings with news of mundane grizzly malfeasance: a bear breaking into garbage cans in the tiny town of Cooke City, Mont., or a grizzly being spotted getting too close to a rancher’s cows somewhere in Wyoming. But a call he got late last summer was much more sinister. On Aug. 25, for the second time in two months, a grizzly bear killed a human being in Yellowstone.

It is hard to overstate how unusual this is. Servheen's bushy handlebar mustache barely twitches as he runs through Yellowstone's many hazards and explains how rare grizzly attacks are in comparison. Park visitors are more likely to die by drowning in one of Yellowstone's rushing rivers, or falling off a cliff during a hike, than they are to be slain by a grizzly. Other dangers abound: Several-hundred-degree hot springs can boil off your skin in huge sheets right before you die; bison can gore you with their blocky horns.

Though he says he was surprised and disturbed by the call on Aug. 26, Servheen’s flat Western tone betrays little of that emotion. As the government’s head bear manager, he must walk a fine line when he’s discussing the dark side of grizzly behavior. He knows that whenever he and the other managers decide that a grizzly must die, there will be lots of opinions from both sides. Everyone wants a say, from local ranchers whose livestock gets picked off by roaming bears, to environmentalists who don’t always agree with the government’s conservation policies. It’s to Servheen’s benefit to sound as neutral as possible when talking about violent attacks.

Servheen got into grizzly management because he wanted to study bear behavior—what types of dens they use, what kinds of foods they eat, what their traveling patterns look like. But mostly he joined FWS because he wanted to repopulate the grizzly bear in the Western wilderness—a line of work he'd wanted to get into since he watched a National Geographic special as a teenager, about a pair of identical-twin bear biologists named Frank and John Craighead. In the late 1960s, after he'd moved out to Missoula from Pennsylvania for his undergraduate degree in zoology and wildlife biology, Servheen earned a Ph.D. with John Craighead as his mentor. “I ended up with a dream job,” he says from behind a desk decorated with a massive grizzly skull and a glass statue of a bear. But the last few months had been more like a nightmare.

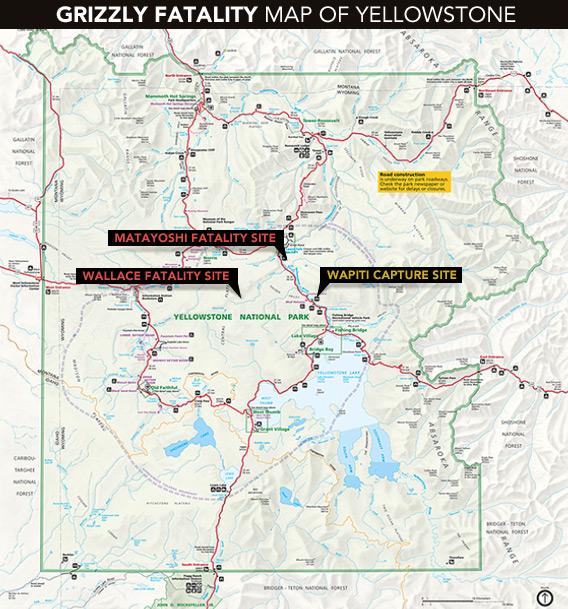

In July, Servheen had been alerted about a bear attack on a couple, Brian and Marylyn Matayoshi hiking on the Wapiti trail in Central Yellowstone. Brian had been killed. Now, Kerry Gunther was telling him about another fatality, this time on the Mary Mountain Trail, about 8 miles from the site of the first killing. Once again, it looked like a grizzly was the culprit. Servheen couldn’t believe the news. Until the summer of 2011 there hadn’t been a grizzly-related death in Yellowstone in 25 years.

Before Servheen, Gunther, and their bear management colleagues could decide what to do, they’d need a lot more information. Was a grizzly bear in fact responsible for this second death? If so, which bear did the mauling? And what were the circumstances that led up to attack—was it provoked or had some hiker just been caught unaware? The answers to those questions would determine whether a precious animal would need to die.

* * *

The first extensively documented death by grizzly within Yellowstone Park’s borders was the fatal mauling of 61-year-old government laborer Frank Welch in 1916. And the park's first extensively documented judicial execution of a grizzly soon followed. Some historians suspect the bear that killed Welch was abnormally ill-tempered because his toes had been ripped off when he escaped from a trap in 1912. Whatever the bear’s motives, though, Welch’s fellow laborers decided that “Old Two Toes” deserved to die for his crimes. Men from the road camp where Welch had been working placed some edible garbage in front of a barrel filled with dynamite. When the bear began to eat, they blew it to smithereens.

That was how grizzlies were treated if they injured humans in the early days of Yellowstone: They were killed.

The first park superintendents were more interested in attracting and accommodating tourists than they were in bear conservation. When Yellowstone was founded as the country’s original National Park in 1872, its goal, as stated in the federal Yellowstone Act, was to be "a public park or pleasuring-ground for the benefit and enjoyment of the people.” To the extent that conserving the grizzlies mattered at all, it was to keep them around for human entertainment. No one was really keeping track of how many were around back then, but there seemed to be enough to keep up Yellowstone’s reputation as “the bear park.”

The idea that grizzlies in Yellowstone were just a goofy sideshow would persist for several decades. Grizzly bears are fairly solitary animals, and there weren’t that many people in Yellowstone at the beginning of the 20th century, so encounters were rare. Even though park visitors were tacitly encouraged to go looking for bears, there was only one bear-related death besides Welch’s in Yellowstone through the 1960s.

But a confluence of factors fundamentally changed the nature of human–grizzly relations. First, visitation to National Parks all over the country exploded. By 1965, more than 2 million people were arriving in Yellowstone every year, more than twice as many as in 1950. There were more opportunities than ever before for people and bears to interact, sometimes in violent ways. At the same time, the publication of Silent Spring in 1962 and the burgeoning environmental movement that soon followed helped popularize the idea that grizzlies should be preserved for their own sake. All of a sudden the government needed a way to resolve interspecies conflicts that went beyond filling barrels with garbage and dynamite.

A fully functioning bear justice system couldn’t be created overnight. First, park officials needed to learn much more about grizzly behavior, and in the meantime, the Craighead brothers’ research made it clear that open garbage dumps in the park were greatly contributing to human injuries. The dumps made bears associate people with food—a recipe for danger. The Craigheads' warnings were borne out in August 1967, on what would be dubbed “The Night of the Grizzlies” by the writer Jack Olsen, who penned a best-seller about it. Two 19-year-old girls, camping 10 miles apart from each other in Glacier National Park, were killed by separate garbage-fed bears while they were sleeping.

The Night of the Grizzlies was a PR disaster for the National Park Service, and led some people to call on the Park Service to destroy all bears on federal land. Yellowstone brass responded to the crisis by creating a hands-on grizzly management program, and eliminating all of the dumps on-site. Once again, the Craighead brothers warned of dangers ahead. Closing the dumps too quickly, they said, would leave the grizzlies confused and unstable. They proposed a more gradual withdrawal of garbage, and the placement of elk and bison carcasses to help bears learn what they might eat instead. But the emergency plan went ahead, and garbage-starved grizzlies were left to seek food outside the borders of the park, where trash was more plentiful and they didn’t enjoy any protection from hunters or ranchers. This led to the shootings of scores of grizzlies by private citizens in the greater Yellowstone region.

By 1975, there were just a few hundred bears left in the park, and the grizzly was listed as being “threatened” under the Endangered Species Act. Diminished grizzly populations in four other ecosystems in the Western United States—including bears in Glacier National Park in Montana, North Cascades National Park in Washington State, and the Selkirk Mountains of Idaho and Washington—would also be protected under the ESA. There were fewer than a thousand grizzlies in the continental United States at that point, down from tens of thousands at the beginning of the 19th century. Now grizzlies could not be shot and killed anywhere in the continental U.S., unless the shooter was acting in self-defense. But park managers in Yellowstone and elsewhere still had the power to execute a rogue bear when necessary, and they needed clear instructions on when and how to use it. In the mid-1980s, a group of federal and state wildlife biologists called the Interagency Grizzly Bear Committee put out a set of formal guidelines—sort of like a penal code for wild animals.

The rules are quite elaborate but essentially they state: If a grizzly hurts someone while acting in a naturally aggressive way, then the bear goes free. If a grizzly acts unnaturally aggressive, though, and injures a person, it must be euthanized. It all comes down to the animal’s state of mind.

It’s a squirrely notion, that a team of government biologists might be able to figure out why a bear does the things it does, or whether any bear behavior could truly be described as “unnatural.” But whatever its shortcomings, the grizzly justice system has been mostly successful over the years since it was introduced, and is reasonably popular. People seem to like the fact that a female bear can kill someone while protecting her cubs and be acquitted of the crime. According to a poll conducted by the Wyoming Game and Fish Department in 2001, more than 70 percent of Wyoming residents believe that grizzly bears are a benefit to the state and are an important component of the Yellowstone ecosystem. They want grizzlies to have the benefit of the doubt.

Chris Servheen wonders if that could change. After two grizzly-related fatalities in one summer, he worries that a forgiving bear justice system might lose the support of the public. The grizzly population has tripled in size since the 1980s, and some bears have started expanding their ranges far outside Yellowstone’s borders. What if people begin to wonder whether preserving bears is more trouble than it’s worth? What if they start agitating for a different kind of bear justice, one that harkens back to the days of Old Two Toes?

* * *

At around 5 p.m. on Aug. 26, more than six hours after a pair of hikers reported finding a body on the Mary Mountain Trail, Yellowstone bear manager Kerry Gunther and four park rangers loaded their wildlife forensics gear into a helicopter and took off from a launching spot in the park’s interior. They flew over open meadows filled with wildflowers and the frigid waters of Otter Creek, which winds through Hayden Valley. It was an overcast evening, and there were lightning cells surrounding the helicopter—remnants of a heavy storm that passed through the area the night before.

The five men landed in some meadows near the Mary Mountain Trail, where the corpse had been found. They flew west of where they believed the body was resting, because they didn’t want to overshoot their mark. They were carrying everything they would need to investigate a grizzly crime: non-acidic envelopes for storing evidence, tweezers for picking up multicolored grizzly bear hairs, tape measures for measuring bear tracks.

Gunther was also carrying a .45-70 rifle slung over his shoulder and a .44 Magnum revolver in a holster on his hip. Either would have been strong enough to kill a charging bear.

In three decades spent working with bears in Yellowstone, Gunther had never had to use his weapon while investigating the scene of an attack, but he had no idea what he was walking into. As the rangers made their way toward the trail, they discussed what to do if they found a bear at the site of the body, red-pawed and hell-bent on defending its kill. It was a tense hike eastward, and the group kept their conversation a loud as possible. Bears are most dangerous to people when you sneak up on them, so they wanted any grizzlies in the area to be aware of their presence.

The investigators weren’t just worried about avoiding a deadly encounter with an aggressive suspect. They were also concerned about the rapidly setting sun. The helicopter they had taken in wasn’t cleared to fly in the dark, so that gave them only two hours to find the body and conduct their investigation.

They had been hiking for about a mile when they finally spotted the pair of legs and boots sticking out onto the trail. At that point they were fairly certain that this was the body of a 59-year-old library superintendent and experienced outdoorsman named John Wallace. Even though he lived more than a thousand miles from Yellowstone in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, Wallace had been to the park five or six times. His wife, Lisa, often joined him on these trips, but in the summer of 2011 he'd left her at home and gone camping in grizzly bear country all by himself.

Now Wallace's body was lying in the long grass next to a downed log and facing up—a sign that he'd seen his attacker and fought back. His face and arm were covered with dirt and a long-sleeved shirt. His other scratched-up arm was sticking out from under a pile of dirt, branches, and grass.

It was an awful, bloody scene: this faceless corpse, half-submerged in soil. But the most disturbing part was that pile of debris under which Wallace’s arm and torso were partially hidden. “We had an indication that the body had been cached,” Gunther says. That’s what grizzlies do to their food. A bear, or bears, hadn't just killed John Wallace. It had eaten him, too.

* * *

Investigating a grizzly bear crime is fundamentally about two things: finding the bear responsible, and figuring out the bear’s motivation. The first question is a matter of old-fashioned police work, very similar to the kind done in human investigations; the second, which determines whether a bear will be released, relocated, or euthanized, involves an expert in bear behavior—a forensic psychiatrist crossed with a veterinarian.

Wildlife biologists like Kerry Gunther help the park's crime-scene investigators by speculating on a bear's emotional state. Based on the evidence at hand, he tries to determine whether a given act of bear aggression might have been a natural behavior—the result of being startled while feeding on an elk carcass, for example, or seeing someone approaching her cubs. If a bear appears to have followed a hiker down the trail instead of backing off, or if it attacked campers while they were asleep, that would be more unusual—the result, perhaps of a deranged grizzly mind.

In a mauling case like that of John Wallace, in which there are no living (human) witnesses, sorting out these categories of bear aggression can be especially vexing. But there's one piece of circumstantial evidence that almost always leads to euthanasia: a half-eaten corpse. Under normal circumstances, the grizzly diet in Yellowstone is about 60 percent vegetarian—roots and nuts, with the remainder coming from pocket gophers, trout, elk, and bison. If the rangers have good reason to believe that a bear killed a human being and then consumed his body, that bear's behavior will be deemed unnatural—and its crime a capital offense.

That's what happened in 1986, when the Park Service sent out a team to investigate the mauling death of 38-year-old mechanic and amateur photographer William Tesinsky. Tesinsky went to Yellowstone to get a photograph of a bear, but he got too close to a very hungry one known to bear managers as No. 59. As described in Scott McMillion’s book on bear attacks, Mark of the Grizzly, rangers arrived on the scene to find his tennis shoe, and a piece of his leg in No. 59's sharp teeth. When they radioed back to headquarters, the Yellowstone bear manager gave the order to kill.

After they shot No. 59 to death, rangers reconstructed the scene. Tesinsky’s tripod was thoroughly mangled, with grizzly hair and blood mashed into it, and his camera’s focal length was set for a photo taken 30 to 50 feet from its subject. Under most circumstances, bear managers would deem such an encroachment a natural cause of aggression for a bear. Add in the fact that it was the autumn of a bad food year and No. 59 would have been desperate to put on weight, and it seemed the mauling might have been an unfortunate accident. But No. 59 was caught eating the corpse, so she had to go.

The zero-tolerance policy for man-eating bears invites an obvious question, though. Once a bear kills someone, whether it's out of some wild-animal psychopathy or a natural inclination to defend her young, why wouldn't she eat the corpse? Everyone agrees that it’s natural for grizzlies to eat carrion—they’re scavengers, after all. When I ask Servheen whether grizzlies can get "a taste for human blood"—whether a grizzly that starts eating people-meat will desire it endlessly—he dismisses the idea. "That’s for horror stories in movies," he says. "Bears don’t get a taste for human blood. There’s no studies that show that."

No studies show it, in part because every time a bear eats someone, they kill it. Not that it’s something that would ever be studied—biologists would never want to take the risk of keeping a bear that had eaten a person in the greater bear population. "We don’t want to test whether bears really get a taste for people,” Gunther explains. "The public wouldn’t appreciate us using them as subjects." That's for horror movies, but it seems like even the bear biologists think there might be some truth to the campfire legends.

On the Mary Mountain trail in August, Gunther and the other rangers were working as fast as they could to gather information from the half-eaten corpse of John Wallace. It was a race against the setting sun, and they were worried about agitated grizzlies in the area. They knew, at this point, that a bear had been feeding on the body, but they didn't know for sure what killed him. Wallace was in good shape with no history of illness, but he was almost 60. Other causes of death—such as stroke or heart attack—were not out of the question.

It was one ranger’s duty to keep a watch out, while the rest of the team scoured the crime scene. But the hunt for clues was frustrating. If only someone had found the body on the day that Wallace was killed, as opposed to the day after, evidence might have been easier to come by: The saliva from the bite wounds on Wallace’s body would have been better preserved, and hairs from his attackers might still have been present on his clothes and camping equipment. But there had been a massive storm on the night of Aug. 25, arriving about eight hours after Wallace was killed. Pounding rain and even some hail had obliterated the first set of tracks and may have washed away other clues as well.

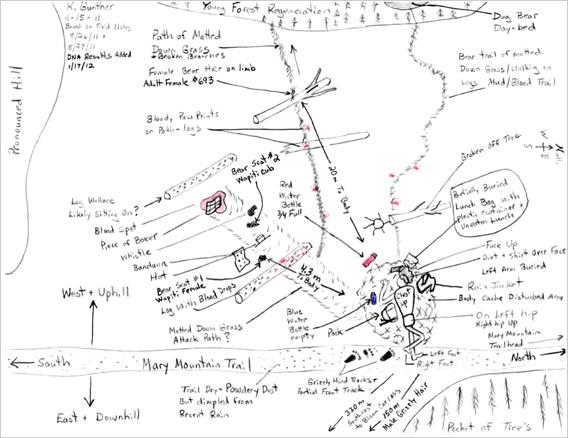

Despite the weather, Gunther could tell there was still much to be discovered. The first thing he saw was a scrap of cloth from Wallace’s boxer shorts sitting in a pool of blood. As they got closer to the body, the team of investigators found Wallace’s hat, bandanna, and whistle. Then they followed the path of matted grass toward the body until they spotted something else—two dark, loose piles of animal droppings about 4 inches in diameter, situated on either side of Wallace's hat and bandanna. This is where a bear biologist like Gunther comes in handy—he knows a pile of grizzly bear scat when he sees it. And if you're looking for a bear's DNA, her excrement is a great place to find it.

Rangers bagged up the scat, along with some hairs they found on and around the body, and resumed the investigation. Wallace’s pack was right next to his body. His lunch, still in its container, was partially buried in the cache pile near Wallace’s head. When they moved Wallace’s body, they would find a half-eaten energy bar underneath him, the remaining portion of the snack neatly wrapped in plastic.

A pair of hind footprints had survived the overnight rainstorm, as did a partial front footprint in the dust nearby. Gunther took out his tape measure and measured the tracks. Because of their size and shape—toes straight across the pad of the paw and a couple of partial claw marks poking into the ground, he knew they had come from grizzlies. Still, there was no way of knowing whether those prints belonged to the killer bear. What if a grizzly had just passed through on its way to somewhere else, maybe the bison carcass investigators had found nearby? But another set of paw prints—these ones tinged with blood—suggested that one bear, at least, had made contact with Wallace’s body.

Though the helicopter had to leave at sunset, Gunther’s team briefly considered staying on. If they did, they would have to hike out 5 miles on foot, perhaps with a killer bear or bears still lurking near the trail. But it might be worth it, if they could find more hair, blood, or scat—anything that a lab could analyze for DNA. It had already been more than 24 hours since John Wallace had died, and it would be another 12 until investigators could return to the backwoods. After a brief deliberation, the rangers decided to leave with the helicopter.

Hand drawn map by Kerry Gunther.

The body was sent to Bozeman, Mont., for an autopsy. When the results came back two days later, they'd learn that John Wallace was in excellent shape and there were no signs of drugs or alcohol in his bloodstream. He had died from exsanguination, or blood loss, from the wounds inflicted by a grizzly bear.

Another set of clues had turned up in the meantime. When rangers revisited the site of the attack on Aug. 27, they found two fresh sets of bear tracks, one big and one small. At some point after Gunther's team took off in the helicopter, and before the next set of investigators arrived in the morning, a mother grizzly and her cub had been nosing around the crime scene, probably looking for the body that was no longer present. Then rangers found slightly older prints from the same two bears, on a log about 20 meters from where the body had been cached. These were bright red, as if mother and cub had just been dipping their paws into John Wallace's bloody remains.

The initial investigation of the attack was over. From the evidence available, it looked like Wallace had sat down on a log near the Mary Mountain trail to have a snack at around 10 a.m. on Aug. 25 when he was attacked. Bite wounds and bruising on his arms indicated that he had faced the grizzly and attempted to fight back. The bear had left bite marks on his back, too, and his torso was partially eaten. It wasn’t yet clear from the autopsy whether the grizzly that killed Wallace was the same one that ate his body. They'd need to wait for the DNA analysis to know for sure.

* * *

At this point, the main suspect in Wallace’s death was a grizzly bear with offspring, whose home range was somewhere in the Hayden Valley—a lush, meadow-filled expanse in the middle of Yellowstone, about 20 miles northeast across the park's Central Plateau from its most famous landmark, the Old Faithful geyser. Rangers knew there was at least one bear that fit the description—and she already had a criminal record. The so-called Wapiti sow had already killed a tourist in July and given some other park visitors a fright.

In June, wildlife photographer James Yule came across the sow and her two cubs, one blond-headed and the other brown, while they were digging for gophers. He’s used to observing grizzlies in the wild—he's taken reams of photographs of them—but this one spooked him. As he shot video footage from his Suburban, Yule noticed that the sow was looking right back at the camera. "She stared as she moved across the road and was looking back at me after she crossed,” he says. The experience was disturbing enough that he warned some nearby hikers to stay away from her.

It’s not so unusual for a sow with young cubs to appear aggressive to a human, though. At that point, the Wapiti sow, which was six or seven years old, had never been trapped, tagged, or radio collared, as about one-third to one-half of the bear population in Yellowstone has been. Despite her forbidding demeanor, she hadn't had any major run-ins with human beings. (All bears involved in management actions are entered into a database.) But in the month after Yule’s encounter, all of this would change. In July, Yellowstone is more crowded with visitors than at any other time of the year, with 900,000 people coming through, and that meant plenty of chances for the bear to get in trouble.

The Wapiti sow’s first violent encounter with a human came on the morning of Wednesday, July 6, with the park still bustling after the holiday weekend. Based on all the evidence gathered by the park rangers in the weeks that followed, the incident began when the sow and her two cubs were grazing and digging in an open meadow below the Wapiti trail. Though the Trail is fairly easy to access, it brings you to the backcountry, and some remote hot springs that few Yellowstone visitors ever get to see.

It's likely the bear didn't feel threatened at first, when the scent of a pair of human hikers, 58-year-old Brian Matayoshi and his wife Marylyn, blew in her direction. The Matayoshis took pictures of the three bears from their perch on the trail above and then kept hiking, with no reason to think they would ever see those animals again.

Less than 30 minutes later, the Matayoshis came face-to-face with the sow on the trail. They started hiking away from her immediately, looking back to see what she was doing. Then Marylyn saw the 250-pound sow lift up her head and start to chase after them. Brian cried out, "Run!"

Bear biologists recommend two strategies for dealing with a grizzly approaching from close range—stand your ground or slowly back away. If the Matayoshis had done either of those things, it's possible the Wapiti sow would have wandered off, or maybe bluff-charged to make sure they weren’t going to hurt her babies. But to see the pair running made her want to chase them even more.

The Matayoshis hadn't gotten far down the path when the Wapiti sow caught up with them. She reached Brian first, knocking him down and raking his scalp. Then she started biting and scratching his right thigh, and punctured his femoral artery. It’s unclear how long the assault continued—Marylyn couldn’t watch. When she looked up from her hiding place behind a downed log, she saw the Wapiti sow standing over her husband. The two made eye contact—a gesture that a grizzly might take as an attempt to intimidate—and then the bear lunged toward her and ripped at her backpack with its claws, before cutting off the attack and running into the woods.

Marylyn Matayoshi doesn’t know how long she waited, motionless, before going over to her husband. She tied her jacket around his thigh in an effort to stanch the bleeding, but it was too late. Brian exhaled his last breath just minutes after the sow and cubs had fled the scene—the first death by grizzly mauling in Yellowstone since 1986.

The same grizzly CSI team that would investigate John Wallace’s death several weeks later did a thorough sweep of the Matayoshi crime scene. The evidence in this case was far easier to interpret. For one, investigators had an eyewitness. Marylyn had seen the attacking bear, both on the trail and in the meadow, and she'd seen her two cubs, one with a distinctive blond face. That alone was enough to make an identification. The Wapiti sow—the one James Yule had filmed in June—was the only bear rangers had seen in the Hayden Valley that matched the description.

It would have been possible to trap the Wapiti sow at that point and euthanize her if necessary. But Servheen and the other bear managers decided to leave the Wapiti sow alone. Her behavior, they thought, was natural considering the circumstances. She attacked the Matayoshis because she was defending her cubs. If one of those bites hadn’t landed on Brian's femoral artery, the rangers thought, he might have survived the mauling as most others do. (There have been more than 125 grizzly bear attacks in national parks since 1900, and fewer than 30 fatalities.) The tragic outcome of the case seemed to be a matter of some very bad luck.

Because bear managers were so certain that the Wapiti sow had been acting in natural self-defense, they didn’t even put a radio collar on her. When they looked for her from a helicopter over Hayden Valley that day, she was 2 miles from the scene of the attack, walking around and foraging with her cubs. They knew they were looking at the bear that killed Brian Matayoshi, but they let her be.

* * *

The John Wallace mauling would take place just eight weeks later, and only a few miles from where Brian Matayoshi had been killed. But Chris Servheen and Kerry Gunther both say that at first they didn’t assume the cases were related. The Wallace investigation faced significant obstacles. The investigators, you’ll remember, didn’t reach his body until a day after the attack. Scientists couldn’t get any DNA from the bear hair and saliva found on Wallace’s body. The genetic material might have degraded in the body bag by the time the autopsy was performed, or washed away in that storm the night after Wallace’s death.

But as the investigation went on, Servheen and Gunther realized that there was mounting evidence against the Wapiti sow. They had the bloody paw prints from a mother bear and cub. Then they found a DNA match, between the scat that had been dropped next to Wallace's hat and bandanna and a sample taken from an animal hair that had snagged on Brian Matayoshi's glasses while he was being attacked the month before. The Wapiti sow—a bear that had already mauled to death one Yellowstone tourist—had been at the scene of the second killing, too.

The fact that she'd been at the scene didn't prove she was guilty, but the evidence continued to pile up. DNA from scat found about 25 feet from Wallace’s body turned out to be a match for her distinctive blond cub. The bloody, big and little paw prints were consistent in size with her own and those of her young cub, and there were no other female grizzlies with similar-aged cubs roaming Hayden Valley, as far as the rangers could tell. She was by far the most likely suspect in the Wallace death. It was time to bring her in.

The easiest way to catch a bear is with something called a culvert trap, named for the tubular devices that channel water. On Aug. 26, the day Wallace's body was found, rangers closed off nearly the entire Hayden Valley, comprising about 10 percent of the Yellowstone parkland, and, in the weeks that followed, they baited aluminum and stainless-steel tubes with animal carcasses in 10 different locations—including the sites of both the Wallace and Matayoshi maulings, next to the rushing water in Otter Creek, and near the burbling geysers of Crater Hills. Starting at the end of August, rangers rode out to check each of these traps on horseback, hoping to find the Wapiti sow.

Photograph for Slate by Jessica Grose.

At first the traps only succeeded in luring some very old male bears, the ones that are most aggressive around carrion. Younger, smaller bears are more skittish about fighting over meat, and so are mother bears with young cubs. Gunther and his men knew the Wapiti sow would be difficult to catch, but when she hadn’t turned up by late September, they started getting nervous. Yellowstone’s bears start to den up for the long winter in October, and they’re generally all hibernating by the end of November. If they couldn't trap her before she went into hibernation, they might lose her for good. In the spring, she could find a new home range somewhere in the deep woods of Yellowstone’s nearly 2.2 million acres, hidden under the forest cover.

It was maximally frustrating, because they were seeing the Wapiti sow and her cubs all the time from their regular aerial missions over Hayden Valley. The larger cub’s blond mug made the trio impossible to miss. But Gunther's crew was hoping to avoid their Plan B, a mission to shoot the bear from the sky with a Telazol-filled dart gun. That would be dangerous for a ranger, who would have to dangle from a helicopter for the shot. It would also be more dangerous for the bear, which could be killed painfully if shot in the wrong place.

The aerial-gunning maneuver was set for the morning of Sept. 29. But on the evening of Sept. 28, bear managers received an automated radio signal from one of their culvert traps along the Yellowstone River, about 6 miles from the site of the Wallace killing. When rangers arrived the next morning, they found the Wapiti sow in the aluminum tube, and she was agitated. Her cubs were darting around the trap, making little bawling noises. It didn’t take much to corral them into a culvert trap next to their mom's—they just wanted to be near her, and they were confused.

On Oct. 1, hair and blood samples from the sow and her cubs were successfully matched to those found at both the Wallace and Matayoshi crime scenes. At that point, the group of federal, state, and local officials who decide on the fate of grizzlies involved in crimes—including Chris Servheen and Kerry Gunther—knew what they had to do. The Wapiti sow was to be euthanized the next day, on Gunther’s birthday.

He had to do so knowing that he would be shrinking a population of about 600 grizzly bears in the Yellowstone region. As a reproductive female, one of about 250 now living in the Yellowstone ecosystem, the Wapiti sow was even more valuable. Bear managers count on having 91 percent of the bears like her survive from year to year to keep the grizzly population thriving.

Servheen and Gunther felt they had made the right decision, but acknowledged they would never know for sure which bear killed Wallace. It would be months before the investigation would be completed, and its full details released to the public. Additional DNA analysis done in January would show that hair found on a log about 20 meters from Wallace’s body belonged to a different female grizzly, No. 693 in their DNA database. After the release of the official report on Wallace’s death in March, Yellowstone’s superintendent Dan Wenk said that he was considering euthanizing No. 693, even though she had no history of aggressive behavior. Such a decision would be one taken in extreme caution, says Servheen. As far as he and Gunther were concerned, they’d done the best they could, based on the information at hand. They also knew that the decision might not be popular, and they girded themselves for blowback.

* * *

Doug Peacock, for one, doesn’t think the government made the right call about the Wapiti sow. "I think it’s to cover their cowardly, bureaucratic ass," he says, gruffly. "You know, because there’s a slight chance of litigation out there. But the bear cannot go to court and speak for itself. It can’t make that argument, and so the bear loses every time."

Photograph by Jessica Grose.

Peacock is a Vietnam vet who has spent the years since he returned from the war studying, photographing, and living among grizzly bears in and around Yellowstone. I wanted to see where John Wallace and Brian Matayoshi were killed, but the National Parks Service had denied my request for an escort into Yellowstone last October.

I drive in with Doug and his wife, Andrea. She’s an environmental journalist who could be described as Peacock’s mobile fact-checker. He’ll say something bombastic, like how he can’t remember a Yellowstone superintendent that he respected, and she’ll chime in with a qualifier—"Finley wasn’t half bad"—or a don’t-take-this-so-seriously laugh.

When we get to Hayden Valley, to the trailhead where John Wallace was last seen alive, there’s a sign proclaiming that the entire trail is off-limits. Peacock thought that since they had euthanized the Wapiti sow weeks earlier, the trail might have been reopened, but no dice. "Jesus. I’ve never seen such a huge area closed," he says. "I’ve just never seen one this big this late in the year. So they’re nervous." Being nervous isn’t unreasonable—the Interagency Grizzly Bear Study Team, the research group made up of federal and local bear managers, is currently defending a $5 million wrongful death lawsuit over an incident that occurred in Wyoming in 2010: A recently trapped grizzly killed a man after bear managers had removed warning signs from the area.

We decide to head over to the Pelican Valley—another grizzly hangout—where the trails are open.

Peacock doesn’t believe there’s such a thing as natural or unnatural behavior when it comes to grizzlies, at least not as the bear managers define it. "It is within the range of the ‘natural behavior’ of any grizzly to kill a human during his or her average life span," Peacock wrote in his memoir of his first 20 years spent photographing and living in the Western Wilderness, The Grizzly Years. "The combination of a grizzly’s disposition on a particular day and the nature of its confrontation with any particular human is also probably unique. It would probably never happen again."

But despite thinking all grizzly behavior is "natural," he believes that some grizzly behaviors are predictable, and he gives me the standard set of instructions for what to do should we encounter any in the Pelican Valley. He tells me, "Just stay behind me and don’t do a thing. Don’t move a muscle. Just stay in a little knot and don’t do anything any of those other people did. Don’t scream. Don’t run."

When Peacock instructs me to pull the car onto a small patch of dirt under a bunch of trees, I’m starting to get anxious. It doesn’t help that after we drove away from Hayden Valley, he had said, "If that trail were open, I would consider this one of the more dangerous grizzly hikes of my life." The bears are in their prehibernation hyperphagic state, he says. They’ll go into their dens for the winter within a month.

Once we're on the trail, Doug’s in front, I’m right behind him, and Andrea is behind me. I keep my head down and try to concentrate on the ground. I’m notoriously clumsy, so I’m afraid I'll trip on a root or a stone sticking out. We’ve been walking for five minutes when Andrea says something to Doug that sounds urgent. I can’t make out what it is but Doug stops short and I walk right into his back.

"Be quiet. Don’t move," Peacock whisper-grunts, at which point I look up to see a mother grizzly with a young cub. They’re about 200 yards from us, digging for roots. The mother bear is pawing at the ground, and her cub sticks close to her. "Back up slowly," Doug says. "If the mother lifts her head, stop moving." We start moving backward slowly and deliberately. I can’t remember being so aware of each step, of the rustling of my hiking pants. I keep looking back up at the bears, wondering what they’re thinking, until we’re a safe distance away, hiding behind a clump of trees. Can they smell us? Do they see us? Are they choosing to ignore us, giving us a small measure of grace?

While we’re out there, I remember something Andrea said to me in the car, about why Yellowstone is so powerful. "Doug’s theory is that the element of risk is what’s important. It’s what makes wilderness wild." We’re so quiet I can hear my own quick, scared, rabbity breaths, and as I revel in my own fear I realize they’re right.

It occurs to me later that this moment perfectly illustrates what Chris Servheen calls "the Park Service paradox." City slickers like me go to Yellowstone to feel humbled by nature, by its sheer beauty and its uncontrollability—that’s part of the purpose of the Park System, it’s there for the enjoyment of the people. But the park is ultimately a human creation: Its boundaries are built and monitored by the government, and the rangers are responsible for keeping its 3 million yearly visitors safe. Doug Peacock might dream of a world where grizzlies can be left alone, but that’s just not possible in the increasingly civilized American West. Sometimes bears need to be euthanized in order to "err on the side of human safety," as Kerry Gunther puts it.

Applying a human-constructed justice system to grizzly bears tries to reconcile this paradox, but it will never be a perfect fix. There are always going to be aspects of grizzly bear behavior that are inexplicable, and that’s what makes them awe-inspiring. That’s also what makes a bear manager’s job so difficult. "As a scientist I always try to seek some kind of logical events that led to this thing happening," Chris Servheen says. When a hunter is gutting an elk and a grizzly attacks him—that makes sense. When a grizzly is defending her cubs, like the Wapiti sow seemed to be when she killed Brian Matayoshi, that makes sense, too. But John Wallace’s death wasn’t like that. He was just sitting on a log, having a snack in the summer sun. "Those cases are puzzling," Servheen says, "and they leave you lying awake at night trying to figure out what happened."