Urban Onshoring

How to bring tech jobs back to the United States.

Photo courtesy Dina Litovsky

Reprinted from

There’s not much to see when you walk out of the subway station at Hunts Point in the South Bronx. A check cashing outfit, a few auto body shops, a weather-worn sign for Bella Vista Fried Chicken, and a billboard advertising $399 divorces, “no signature needed.” This New York neighborhood has a landscape as bleak as its reputation. If you Google it, related searches include “Hunts Point crime,” “Hunts Point junkyards,” and “Hunts Point prostitution.”

But if you keep walking south on Hunts Point Avenue, past the 99-Cent Dreams store and the smiley-face mural that reads “You Can Do It” in both English and Spanish, you’ll come to a notably new storefront that’s all windows and exposed brick. From the street, you can see the L-shaped window seat, filled with colorful pillows to match the rainbow-hued pipes overhead.

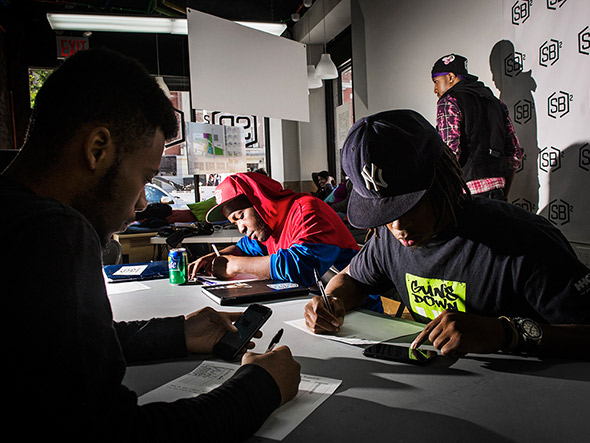

Inside, seven young men and women are hunched over laptops and smartphones, headphones and hoodies on. Every so often, they’ll scribble something on the paper spreadsheets beside them. They’re flipping through a smartphone app called GameChaser, an online service that advertises itself as a one-stop shop for gaming news and updates, but this isn’t just for fun. They’re looking for bugs in the app, and each time they find one—a slow-loading page here, an irrelevant search result there—they make a note.

This is the home of Startup Box, a company that aims to transform Hunts Points into a new hub for computer software testing. Over the past 20 years, so much of the country’s “quality assurance” testing—QA, in industry lingo—has moved overseas to places like India and the Philippines. But Startup Box seeks to bring many of these jobs back to the US—specifically to places like Hunts Point, where they’re needed most.

Sitting at a plastic folding table inside the company’s offices one crisp but sunny morning in early fall is Jermaine Rampersant, 21. He describes himself as a “hardcore gamer,” and he doesn’t use these words lightly. “It’s a lifelong journey,” he says, “and it’s been evolving everyday.”

He’s not alone. Desiree Aultman, 30, has a bachelor’s degree in video game programming. Leon Sterling, 24, plays fighting games competitively, and he says that when he heard about Startup Box, he was “like a shark smelling blood.” And then there’s 24-year-old Kevin Gumbs, who insists he’s been gaming “since birth.”

This is by design. In building Startup Box, husband and wife team Majora Carter and James Chase are focusing on QA testing for games and game-related apps like GameChaser—at least initially. To recruit testers, they even hold gaming tournaments in and around Hunts Point. If the company wants to compete with dirt-cheap testing centers in India or the Philippines, Carter and Chase know they must offer clients something extra. By hiring gamers to test games, they’re selling not just a testing service, but a kind of focus group.

For the last year, Startup Box has been hiring small teams like this one, putting them to work on jobs that last anywhere from a few weeks to a few months and paying them about $12 an hour to test apps during a standard 30-hour work week. Carter and Chase call it “urban onshoring,” a way of tackling the area’s massive unemployment problem, while simultaneously giving the tech startups down in Manhattan an alternative to the inefficient and often low-quality testing services they find overseas.

It’s a lofty goal, but Carter and Chase aren’t alone in pursuing it. Just down the road from the storefront, work is underway on a new 45,000-square-foot facility called the Urban Development Center, which will soon be filled with hundreds of testers from around New York City. It’s the result of a partnership between Per Scholas, a local IT workforce development non-profit, and Doran Jones, a startup consulting firm that does testing work for some of the largest banks and media companies in Manhattan.

“This is probably one of the largest, if not the largest, infusions of good paying jobs in this area in a very, very long time,” says Plinio Ayala, who has been president and CEO of Per Scholas since 2003. “It could really transform this community.”

But both operations—Startup Box and Doran Jones—paint their new operations as more than just charity projects. As offshoring becomes more and more problematic in the ever-changing tech world, they say, onshoring is a major market opportunity. They can make outsourcing more efficient and diversify the talent pipeline in tech, in addition to bringing some much needed jobs back to the U.S.

Both StartupBox and Doran Jones have plans to replicate this urban onshoring thing in other cities. But first, they have to prove that it’s more than just a nice idea, and they have to do here, in the place that StartupBox co-founder Majora Carter calls “the land of promises not kept.”

No Place Like Home

Majora Carter grew up in Hunts Point. It’s where, as a kid, she saw a wave of arson burn two buildings on her block to the ground in one summer and where her older brother, a recently returned Vietnam veteran, was shot to death in a drug war. From an early age, Carter remembers being told that she was one of the “bright ones” and that, as such, she should leave the Bronx as soon as she could.

There was a notion, she says, that success was measured by how far away you got from the community. “It’s engrained in your head that good things do not stay,” she says, sitting in her light-filled office, just a few blocks from Startup Box. “Good things do not stay.”

Today, Carter has become something of an urban revitalization savant, working to ensure that in the future, people like her will have more reasons to stick around. She travels the world with her consulting firm Majora Carter Group, helping businesses, schools, and even government agencies develop revitalization strategies. But Hunts Point is where her heart is. She’s the one who painted that smiley face mural on Hunts Point Avenue. “That’s the kind of thing Majora does on weekends,” says Chase, Carter’s husband, with a laugh.

In 2004, Carter became a local celebrity after convincing the city of New York to spend $3 million to turn an illegal garbage dump on the Bronx River into a public park. She parlayed that success into the launch of Sustainable South Bronx, a non-profit that trains Bronx locals in the skills they need to land these new green jobs. For this work, Carter received one of the Macarthur Foundation’s esteemed “genius grants” in 2005.

“Yes, I made my mark in the environmental world,” she says, acknowledging the immense collection of awards and accolades that line her office walls. “But it was always simply a tool to empower and support the local community.” Now, she says, tech is becoming that tool, which is why, in recent years, she and Chase have turned their attention to cultivating a tech ecosystem in the Bronx.

Building a Pipeline

That proved more difficult than they expected. In 2012, they attempted to launch a co-working space, but found that there weren’t even enough tech workers in the Bronx to fill it. They tried convincing software companies to open offices there too, but understandably, Chase says, no one took them up on it. They even launched an after school program teaching kids to code at a local high school. It was successful—easy even—but neither Carter nor Chase felt it would have an immediate impact on the community. Then, sometime last year, they met a Nickelodeon executive who explained what a headache quality assurance testing can be.

Over the past 20 years, so many businesses have jumped at the chance to get routine IT work done at bargain basement prices overseas. But now, overseas wages are rising. Businesses are struggling to cope with all the inefficiencies that come with a 12-hour time difference. And the technology that needs testing is getting more complex. Be they Wall Street banks, tech startups, health care companies, or entertainment outfits like Nickelodeon, some businesses are now beginning to look for testing that’s closer to home.

“IT work is not strictly siloed away from the rest of the organization anymore, so it’s becoming harder to think of it in this geographically separate way,” says Prasanna Tambe, an associate professor at NYU’s Stern School of Business, who researches the IT workforce.

Photo courtesy Dina Litovsky

That Nickelodeon exec told Carter and Chase that QA was the one thing that always seemed to be gumming up the works, and yet, the testing itself was really the easier thing to do. “We were like: ‘The easiest thing? We need easy things,’ ” remembers Chase, who is white and grew up in rural Wisconsin, but speaks with ease about his adopted home of Hunts Point. “We have a population here with very low educational attainment, and very little confidence in their ability, even if they do have a degree. We need something that’s entry level. That’s how you build the pipeline.”

Since then, Startup Box has completed projects for the likes of Nickelodeon, the mobile gaming studio TreSensa, and, most recently, Gust, the company behind digital.nyc, New York City’s new online hub for tech companies. In each case, the company has drawn testers from the Bronx, and the only requirement, Chase says, is that you’re “not a cocky bastard.” He and Carter have hired single moms, guys fresh out of jail, and college dropouts. Recently, they found out that one of the crewmembers is homeless. “We’re happy to absorb the social kinks and quirks of this neighborhood, because we’re into that,” Chase says. “We want to see this neighborhood thrive.”

For now, Startup Box is backed by philanthropic donations and has done all of this work for free, but, in a few weeks, it will begin work with its first paying client. It’s not that clients haven’t been willing to pay, Chase says, but because he and Carter want to be absolutely sure their system works before they start charging. “We’re trying not to get ourselves to an expectation hurdle that we can’t meet because someone paid us,” he says. “We’re being upfront that we’re not experts in this, but we know there’s potential.”

It’s Not Altruism. It’s Business.

When they launched Startup Box, Carter and Chase say they were unaware of Doran Jones, the consulting firm that’s building the Urban Development Center just two miles away. But when they heard about it, they viewed it not as competition, but as validation. “We were like: ‘We’re brilliant. We’re so friggin’ brilliant,’ ” Carter says, laughing.

The Urban Development Center lends this whole urban on-shoring concept some serious street cred, primarily because of a man named Keith Klain. Klain is the co-CEO of Doran Jones, and the driving force behind the center, but before that, he spent years as the head of global testing for Barclay’s Capital, traveling the world setting up and managing software testing operations in India and Kiev. For Klain, bringing these jobs back to the US is not just altruism. It’s business.

Klain’s Barclay’s years were draining. He spent half his time on the road or in flight, and over time, he became convinced that after factoring in the cost of travel and time lost to cultural miscommunications, offshoring wasn’t actually all that cheap. Overseas, he was working with large IT service providers, with no real expertise in testing. If he could build a specialized testing workforce back in New York City, not only would Barclay’s save money on time and travel, but the quality of the work might be superior.

So Klain decided to launch a little experiment with the well-respected workforce development firm Per Scholas. Last year, he developed an eight-week training course to teach Per Scholas students how to test software, hoping if all went well he could begin shifting some of Barclay’s overseas testing jobs to the States. But in the end, he was so impressed with the Per Scholas grads that this year, he left his job at Barclay’s, and joined Doran Jones to lead its new testing services division.

Klain admits that initially he’d been skeptical that Hunts Point was the best location for this operation, but the area quickly won him over. “It never occurred to me to look in the Bronx,” he says. “You just wouldn’t think that it’s going to draw people with the right mind frame to do great tech work. And I was so, so wrong about that.” The Urban Development Center—built inside Per Scholas’ headquarters—is now set to employ some 450 testers, 80 percent of whom will be poached directly from Per Scholas.

“Life Changing Money”

Inside Per Scholas’ headquarters, across the street from an old Sabrett hotdog factory, about a dozen students have split into groups of threes, and they’re huddled around the computers that line the classroom. Sitting at the back of the room is Paul Holland, Doran Jones’ head of testing and one of the instructors leading the training course. “I’ll probably hire a lot of them,” he says, gesturing to the students.

Holland has been in the testing industry for nearly two decades, and he’s a firm believer that testing can be a fruitful career, not just a stepping stone to one. Testing, he says, isn’t some mindless or repetitive task. When done right, Holland believes, it’s a craft, a serious exercise in critical thinking.

Photo courtesy Dina Litovsky

Which is one reason why here at Per Scholas, the bar is set substantially higher than it is at Startup Box. The classes are free, but to get accepted, students have to pass a lengthy entrance exam and an in-person interview. Once they pass, it’s eight weeks of hardcore—some called it “grueling”—training in different coding languages and crash courses in agile development.

“By the third week, I wanted to quit. I really did,” Cochrane Williams, 37, tells me. Williams served in the Army Reserves from 2000 to 2004 and worked as a photographer and digital technician on photo shoots after that. But in recent years, he says, his freelance gigs had become inconsistent. “I wanted something more stable, especially because I have a daughter and wanted to be able to provide for her,” he says.

The average Per Scholas student reports just $7,000 in annual income before entering one of the training programs. Most are either young people just starting their careers, unemployed, or people who have been recently laid off or are in the middle of a career change. Those students who Doran Jones hires will start at $35,000 a year, with a $10,000 raise after one year and another $10,000 the year after that. Those who rise up the ranks to become test managers will make anywhere from $80,000 to $100,000 a year. Klain calls it “kind of life-changing money.”

It’s little wonder then that Williams and his fellow students are willing to power through the tough days. “There are two companies I want to work for,” Williams says. “One is Doran Jones, and the other … I don’t know if I want to say it. I don’t want to jinx it.”

The Elephant in the Classroom

But Williams also admits there’s an “elephant in the room.” Most software testing jobs are still offshored.

Though Klain, Carter, and Chase are making headway here in the Bronx, the numbers are still against people like Williams. According to data released by the Department of Commerce a few years back, during the 2000s, multinational corporations laid off 2.9 million people in the US Meanwhile, they hired 2.4 million people overseas. Many of those jobs, even supporters of this on-shoring movement agree, are never coming back.

“I don’t think you’re going to see the reshoring of jobs which are pure cheap body labor. That’s not happening,” says David S. Rose, a New York City–based angel investor, and the CEO of Gust, a platform that connects entrepreneurs and investors. Rose is the one who hired Startup Box to do the quality assurance work for digital.nyc this fall, and now, he’s the company’s first paying client. Rose clearly believes in on-shoring, and yet, he says, in order for it to take off, businesses will have to trust that they’re truly getting a level of service they couldn’t find for pennies overseas, and that may prove to be a tough sell in the short-term.

Meanwhile, there are other, more shallow and sordid hurdles that these groups may have to overcome, like the way decision makers in corporate America view neighborhoods like the South Bronx. “Our guys don’t look like the traditional consulting firm,” says Matt Doran, co-CEO and founder of Doran Jones, noting that one hedge fund even rejected Doran Jones’s pitch for that very reason. “It was really disappointing and something I never expected,” he says, shaking his head.

But those kinds of reactions are the exception, he says, not the rule. In fact, Doran Jones now has $11 million worth of contracts set to begin as soon as the center opens. They expect 150 testers to move into the center by the first quarter of next year, with another 300 moving in after that. Meanwhile, the company recently closed a deal with a bank in Tampa, where is also set to open another Urban Development Center early next year. This time, it’s working with the White House and Department of Veterans Affairs to employ veterans from the nearby MacDill Airforce Base.

But Doran says all this is just a start. “CitiBank has thousands of testing roles, and that’s just one bank,” he says. “There are thousands and thousands of roles out there, and once one guy seems to have made it work, everyone else is going to want to take the plunge.”

Doran and Klain believe they’re going to have so much demand from companies, in fact, that they’ve committed to share 25 percent of revenue from the Urban Development Center in the Bronx with Per Scholas to help the non-profit scale its training program. “I think very, very quickly we’re going to be like: ‘Ok. We need to run a lot more training than we thought,’ ” Doran says. “So it’s the calm before the storm right now.”

Imagination Run Wild

Today, the Urban Development Center is a vast expanse of open space, with exposed insulation overhead, and just enough natural light to cast long shadows on the bare floors. But in just a few months, if all goes according to plan, this cavernous place, which sits on an unremarkable road across from a hotdog factory in the Bronx, will be filled wall to wall with tech work. It seems an impossible feat, and there’s no guarantee the thing will work. After all, just because they built it doesn’t mean businesses will come.

But what if they do? And what if it catches on? What if tech work could unify—instead of divide—communities in urban centers, from San Francisco and New York City? Even Klain, business-minded as he is, can’t help but let his imagination run wild with the potential impact a place like this could have on a place like this.

He says that recently, a potential client tried to poke holes in his plans, telling him Doran Jones is going to have a massive attrition problem once clients start poaching his employees. But Klain just laughed. “I said: ‘Honestly, if at the end of the day my biggest problem is I’ve created such a hotbed of tech talent in the South Bronx that I have an attrition problem, I’m going home.”

More from Wired: