This is a story about how the airport became the setting for the Great American Freakout. Once an icon of progress, then another stale waiting room of modern life, the airport has now entered a third phase.

This summer, Ann Coulter threw a three-day tantrum over a Delta seat assignment, comparing the airline gate attendants to Nurse Ratched, the sadistic warden who rules over the lunatics in One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. There was some truth to the observation. It was the latest incident in a year of airport fracases—including a brawl at the Spirit Airlines counter in Fort Lauderdale, Florida (May), the concussion of the 69-year-old David Dao who wouldn’t relinquish his seat (April), widespread pro-immigrant protests (January), two full-on panic stampedes one year ago, and a steady drumbeat of racial and religious profiling at security and immigration—that have confirmed the airport’s new role in American life as the marble-floored home of our national, fear-fueled psychosis.

The airport is, on the one hand, as representative a civic space as America has. Nearly half of American adults fly commercial each year, making the airport nearly as common a shared experience as the voting booth. It is also roiled by the ceaseless friction of its many internal borders, real and felt, that separate safety from danger, admittance from expulsion, brown from white, the rich from the rest. Real anxiety has swelled in this liminal space for decades, as airlines grew stingier, the security state grew stricter, and the borders in airport basements grew busier. But as with many conflicts in American life, the rise of Donald Trump has both clarified and exacerbated the fault lines.

This was evident in January, when the Trump administration unveiled its travel ban and thousands of protesters assembled at terminals across the country. But that was only a reminder of all the ways in which the airport has become a symbol and a stage: for the related and unrelated detentions of visitors, immigrants, and American citizens; for flare-ups over dress, language, and skin color; for increasing stratification by class; for massive delays borne of computer failures; for that dangerous hunch that America ain’t what it used to be; and for the aggrieved knowledge that it isn’t all it could be. It is a temple for a political era built on paranoia, as good a symbol for our age as the corporate skyscraper was for the postwar era and the suburban megamall was for the end of the century. The airport is the place to understand America today.

People who run airports know this. You can see it in their attempts to soothe. We now have art designed to keep us calm in the terminal. Ponies. Herds of kindly dogs. A therapy pig, in San Francisco. Chairs that rock and chairs that massage. Jazz music and country music. Mostly, we keep our aviation-related anxieties at bay with chemistry. The airport bars open early and endow patrons with both fortitude and an aura of righteous intoxication rarely found in morning drinking. Savvy travelers not among the nearly 1 in 10 Americans who have prescriptions for Xanax and its ilk nevertheless procure their favored pills for air travel. Take one just after passing through security to sink into an Eames tandem sling, that familiar, inclined bank of chairs.

Whatever we do, it’s not working.

* * *

In 1962, New York’s Idlewild Airport inaugurated Eero Saarinen’s TWA Flight Center, a swooping concrete-and-glass icon of jet-age glamor. The building incarnated an idea of air travel’s allure that lingered like a contrail in the national imagination. In his 2015 book The End of Airports, Christopher Schaberg diagnosed the end of an idea: “The end of airports as romantic places; the end of airports as sites of excitement; the end of airports as apexes of travel culture. The end of airports means the end of our ability to appreciate airports, to inhabit them as dynamic, fascinating, forward-looking spaces.” In his latest book, Airportness, he has turned darker still: “It is a miserable place—you can see it on everybody’s face.”

But the romantic idea of the airport has been dying at least since the hijacking crisis of the 1970s, when American airports began to install metal detectors. Gradually, all aspects of the flying experience would be securitized. Metal detectors first sliced the grand TWA atrium in two decades ago, dispensing the sense of the airport as a genuine public place, where lovers parted at the jetway and the homeless could nap undisturbed, and marking the rise of the age of terror and security. As late as 1997, J.G. Ballard, writing of the world’s international terminals as a “discontinuous city” of global travelers, could claim that “above all, airports are places of good news.” But the raft of changes implemented since 9/11 have amplified security’s psychic cost.

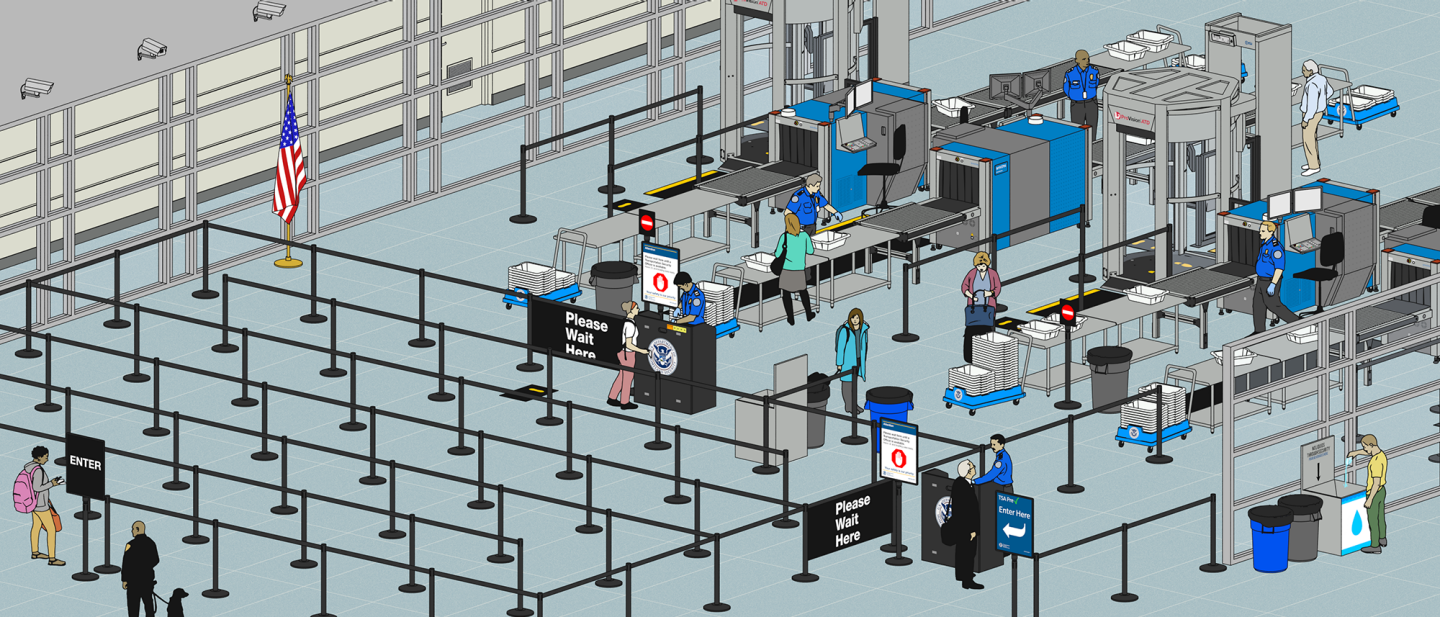

It’s not clear how much the Transportation Security Administration’s methods are protecting us: In a 2015 investigation, undercover agents succeeded in smuggling weapons past screeners in 67 out of 70 attempts, and the agency’s acting head was reassigned. The drawbacks are easier to perceive. The screening requires you to expose yourself, both to the eyes of agents (see the ex-screener Jason Edward Harrington’s confessional “Dear America, I Saw You Naked”) and to fellow passengers, who watch you disrobe. Bags are unzipped to put underwear on display like on a backyard laundry line.

“Taking off shoes,” Harvey Molotch writes of one of America’s more frustrating air travel requirements in Against Security, “makes bodies touch foreign surfaces in unaccustomed ways, bringing to mind the ass on the restroom toilet seat.” Molotch argues that the prison-visit style of airport security is a perpetual worry machine, stoking the concern that justifies its escalating rigors. A design firm hired by the TSA argued that the unpleasant nature of checkpoints was hurting security procedures by giving all travelers the sweaty, nerve-wracked mien of terrorists and drug smugglers, and illustrated the point with photographs of a shark in calm waters (easy to see) and rough waters (invisible).

As with mass incarceration, efforts to reform airport security are hamstrung by politicians and administrators who would prefer to inflict hassle on millions than be caught making one mistake. Normalcy won a rare victory over the security state in 2005, when small scissors, screwdrivers, and pliers were again allowed in carry-on bags over the objections of Congress. (“This is the equivalent of handing back the box cutters to the 9/11 hijackers,” Rep. Ed Markey wrote. Hillary Clinton introduced a special bill to stop the policy.) The exception proves the rule: In 2013, the TSA was set to allow pocket knives and golf clubs on planes before the policy was overruled by lawmakers.

These protocols, like other airport routines, extend a burden beyond the terminal. No traveler can set his or her alarm or pack a tube of toothpaste without thinking about the TSA. The years since Sept. 11, 2001, can be measured out in 3-ounce bottles and other security restrictions. Shortly after 9/11, my sister got carsick on the way to the airport. At the time, there were no trash cans in the check-in area, and so my mother passed the plastic bag of vomit through the metal detector. This story is dated, but only because you can no longer get a bag of vomit through a metal detector.

It’s the conditioning effect of these rituals, as much as terrorism itself, that makes even false alarms so harrowing. Last August, a mass panic enveloped New York’s John F. Kennedy International Airport, sending thousands of travelers fleeing from a phantom terror attack. The false alarm spread between terminals, and flights were delayed nationwide as terrified travelers stormed the tarmac, hiding behind jet wheels and luggage carts or running for the safety of the Atlantic Ocean. What set them off, apparently, was the collapse of a line of bollards whose clack-clack-clack against the floor sounded like gunshots. Two weeks later, police evacuated four terminals of LAX after a phantom shooting, while in Terminal 4, panicked passengers ran willy-nilly. Outside Terminal 6, they scurried down the sidewalk with their rolling luggage, heading nowhere at all.

* * *

As this everyday security check unfolds upstairs, a more substantive vetting process is underway below. For decades, America’s international airports have been an increasingly important port of entry for visitors and immigrants. In 2005, 81 million people—19 percent of international travelers—entered the U.S. by air. By 2015, that number had risen to 112 million, and 29 percent of international arrivals. (Those numbers underestimate the central role of airports, since hundreds of thousands of commuters cross the U.S.–Mexico border every day and are counted multiple times.) Just as airports are places where America must be defended from terrorism, they are frontiers through which immigrants, foreigners, and American expatriates pass onto U.S. soil. They are borders, with their attendant violence, nestled at the heart of domestic life.

This has occurred despite laborious efforts in Washington to push border functions out of our airports, through a series of international data-sharing negotiations, the export of biometric sensors to visa application sites abroad, and supplementary security requirements for U.S.-bound flights. “With a virtual border in place,” the security theorist Gallya Lahav writes, “the actual border guard is meant to become the last point of defense rather than the first.”

At least, that is the idea. The 2014 Ebola crisis demonstrated it hadn’t quite worked out that way. That summer at Newark Liberty International Airport, New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie detained Kaci Hickox, an American nurse who had treated Ebola patients in Sierra Leone, placing her in a mandatory quarantine at a Newark hospital. Trump tweeted about the Ebola outbreak more than 50 times, calling for a travel ban and opposing the return of two infected U.S. aid workers. “The U.S. cannot allow EBOLA infected people back,” our future president wrote. “People that go to far away places to help out are great-but must suffer the consequences.”

It was a stance that, in its callousness and shallow thinking, anticipated Trump’s ham-handed attempt at a Muslim ban. On Jan. 26 of this year, the country’s international airports once again reprised their role as a conflict zone. Holders of visas and green cards arriving from Afghanistan, Iraq, Iran, Libya, Somalia, Syria, and Yemen, some of them refugees, found that their legal status had changed overnight. After months of planning, they were imprisoned in the airport.

So it was the international airport, not the Mexican border or an Immigration and Customs Enforcement detention center, that became the first testing ground for the Trump administration’s strident xenophobia. And concurrently, the site of the first, substantive protests against it.

On the Saturday after the ban was enacted, thousands of protesters convened in the parking lot outside JFK Terminal 4. Inside, U.S. representatives, lawyers, and the families of the detained arrivals struggled to determine where authority in the airport lay, which parts of the terminal belonged to whom, and who was responsible for directing the agents of Customs and Border Protection. “Call the president” was the response. We now know that CBP was deploying some kind of centralized strategy to flummox lawyers and members of Congress . But navigating the administration’s reversals often fell to the rank and file.

The vision of the airport as an austere, Taylorized space, where even the architecture is mathematically deduced (150 square feet per design-hour passenger is a common metric), has fallen away to reveal a deeply human frontier, in all the worst ways. A 2005 report by the U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom determined that there was “extreme” variation in the way that asylum cases were handled at different airports. In the past five months, we have seen the agency’s worst actors deploy their cynicism at the airport border. A French Holocaust historian was detained for 10 hours in Houston. A 70-year-old Australian children’s book author was detained and questioned in Los Angeles. Customs agents checked IDs on the jetway of an arriving, domestic flight. Muhammad Ali Jr., the son of the heavyweight champion, was detained in a Florida airport and asked about his Muslim faith. And those were just the names we knew.

* * *

Whether security and customs inspire reassurance, anguish, or outrage, there is a third and overarching gantlet at work in the form of economic stratification. The airport is to America’s petite bourgeoisie—the small-time capitalists and traveling salesmen who delivered us to Trump—what the factory is to the white working class: a symbol of how much better things used to be. (And the president agrees.) But there is a more widely shared feeling that the airport experience is a reminder of one’s paltry but declining status.

The oldest, basic sorting mechanism of ticket sales has been supplemented by a variety of market incentives, with the path to the plane (and back from the plane) lit by buy-ins and buy-outs: baggage fees, seat fees, concession fees, TSA Precheck and Global Entry, travelers’ clubs, and finally the unseemly bidding process to remove the most cash-poor, time-rich SOB from the plane. Airlines earn lower marks on customer satisfaction surveys than loathed institutions like the U.S. Postal Service and social media. When things go awry, the airport experience encapsulates that peculiar, desperate feeling of the modern American economy. Not the balm of total helplessness, but the regretful hunch that if you had just done one thing differently—routed yourself through Houston instead of Denver, gotten in line earlier, not gotten disconnected with the help line—you might be on your way to where you want to be.

Most gripes about the airport stem from the same No Exit complaint that motivates so much worry in America today: There are simply more people there than there used to be. More kids in your school district, more buildings in your neighborhood, more cars on your road, more people who don’t look like you or talk like you at the mall. Or at the airport. Tickets are cheaper, and the airport experience feels cheaper too. Democratization is stressful; tight quarters serve as the kindling for fires of racist fury (and all kinds of other bad manners).

Private jets and lounges have siphoned off onetime airport luxuries. Thanks to higher baggage fees, Americans increasingly lug their possessions through airports themselves. Not only is an airport delay an extended confrontation with your peers in a seating area, but with all the things they carry: blankets, neck pillows, hair brushes, 30 generations of digital devices—a state of disarray bordering on the domestic. To be in the airport is to inhabit Zeno’s static moment that movement requires. “It is dead time,” Don DeLillo wrote. “It never happened until it happens again. Then it never happened.”

A structural shift in the industry’s economics, spurred by a string of corporate mergers, has added a spark. Small- and medium-size airports have declined as more and more flights are routed through megahubs. Domestic boardings rose 7.7 percent between 2005 and 2015, but more than two-thirds of that gain occurred at the nation’s 10 busiest airports.

It can be difficult to untangle the lived airport from the airport of the mind, but it is easier with airports than with other buildings. Because each one is a glassy, highly regulated remix of its peers, with the same marked-up Dasani and magazines for sale, one airport can easily stand in for many. The airline whose hold music plays softly as you sink into a worn-leather every chair and watch a day and a vacation slip away could be any airline. The tarmac looks the same. The whole system, from the entry through security to the exit past the border agents, is a reminder of how little control you have—not just economic power, but even, for the moment, power over your own movement. From David Dao to the LAX stampede to delay-induced tantrums, these viral acts of airport chaos draw power from this sense of widespread agitation, like storms from a heated sea.

* * *

More from this series:

To understand why air travel has gotten so dreadful, just look at its labor force.

The factors that make travelers cranky are tightly intertwined with the reasons why pilots, flight attendants, and other aviation workers are learning less and less. And it’s partially our fault.

By Jeff Friedrich

But if the experience for everyone is so bad, why is airport retail booming?

That’s exactly why. The factors that immiserate travelers benefit retail sectors that would otherwise struggle in airports the way they do in the real world. Airport retail has guaranteed foot traffic and no competition from e-commerce (when you need new earbuds right before a flight, you’re not hitting up Amazon). They also benefit from delays and the fact that airlines are less likely to give you free food or drink.

By Daniel Gross

There is still one way to dodge the hellscape: small airports.

Just look at the Westchester County Airport in White Plains, New York. It turns out that airport function is not helped by scale—the bigger the building, the more prone to morasses it is. Smaller, it turns out, is better.

By Daniel Gross

If you must navigate an airport, at least make the best of it.

A pilot’s tips for appreciating what there is to appreciate about air travel. Airports are destinations of accidental wonder, places an extra 10 minutes can reveal the marvel of travel still beneath the unpleasant surface. Take in the departures board, admire the small variations in culture between places that are all quite similar, people-watch, gaze at the architecture, and savor the exit.

By Mark Vanhoenacker

But not everyone can, of course. Being hypersurveilled in airports is now a part of being brown in America.

A reflection by an expert on surveilled communities on how his own experience is deepened by his day job and the fact that he is Indian. Like a lot of people, he opts out of the scanning machines, meaning instead he gets a physical patdown—a process that has become uncomfortably more invasive in 2017.

By Prashant Sinha

And the net of scrutiny catches even those people who need accommodation.

The devices that make life easier for people with medical conditions—like enhancements for diabetics—make life a much bigger hassle in the airport, and the subject of almost-performative scrutiny from the TSA, despite the agency’s attempt to improve its treatment of such passengers.

By Jacob Brogan