Immigrants to America used to pass beneath the Statue of Liberty on their way into New York Harbor.

These days, they come around a blind corner into Terminal 4 of John F. Kennedy Airport. There is no New Colossus here, but there are long-lost cousins with flowers.

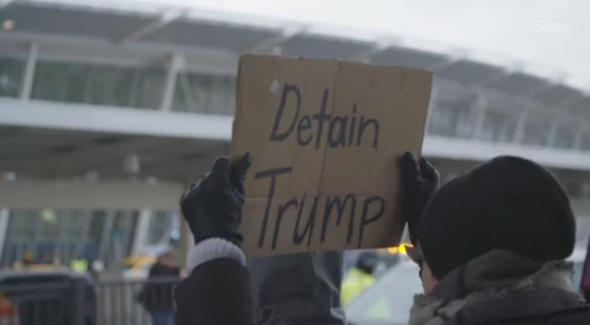

On Saturday, immigrants to America saw something else: a boisterous crowd of protesters chanting slogans in defense of refugees and against Donald Trump’s immigration executive order, which bars people from seven Muslim-majority countries (Iraq, Iran, Syria, Sudan, Libya, Somalia, and Yemen) from entering the United States. Cars leaving the terminal honked their approval; demonstrators lined the open-air levels of the parking garage, spilled along the fence near the TV station vans. “No hate, no fear, refugees are welcome here.” “Fuck the wall, we’ll tear it down.” “I-L-L-E-G-A-L, this shit is illegal.”

But those were the lucky ones. In the bowels of this airport and others around the country, dozens of visitors found that their paperwork—acquired over many months, and at great cost—had become invalid as they flew over the Atlantic Ocean.

Late Saturday evening, a federal judge issued a stay on the order after a suit brought by the American Civil Liberties Union, suspending the ban for detainees and passengers in transit. But twenty-four hours of panic had taken its toll on dozens of families, some of whom spoke to me that afternoon.

People like Amina Mohamed Abdulaziz Ahmed, a 66-year-old woman emigrating from Yemen to live with her son, an American citizen. Her family waited by the Panini Express in Terminal 1, worried what had happened in the six hours since her 11:30 a.m. arrival. She did not speak English and suffered from diabetes and high blood pressure.

“If she collapses, who is responsible?” said her son, who had come from Missouri to greet her. “Is Donald Trump responsible?”

If the protest was loud and organized, the scene inside the terminal was one of quiet chaos. U.S. Reps. Jerry Nadler and Nydia Velazquez roamed Terminal 4, trying to figure out how border agents were deciding whom to let into the country. “I have been talking with agents from Customs and Border Patrol,” said Velazquez, a Democrat from New York. “I can tell you that they are overwhelmed, they want to do what is right, but they have not been given clear guidelines as to how this executive order applies.” There were reports of beleaguered customs agents breaking down in tears, unsure how to follow a hastily drafted executive order that, in addition to barring millions from entering the United States, trapped half a million permanent residents inside.

Trump, in his way, had given New York a true Third World airport, where government documents meant nothing, police pressure and misinformation were delivered via phone call, and families were split in two by political whim.

Summoned by an email from the International Refugee Assistance Project, lawyers (specializing in immigration, but also discrimination, bankruptcy, and more) had arrived by the dozen. At the Central Diner, an Iranian family sat glumly over uneaten hamburgers while six young lawyers on laptops prepared a habeas petition on behalf of a sister with a tourist visa who had been detained. A bouquet of flowers lay on a chair.

No one knew how many visitors with valid paperwork were being held since Trump’s executive order was signed on Friday night. There was no list. Instead, volunteers canvassed the arrivals hall, asking: Are you worried that a friend or relative has been detained?

Mohamad Zandian, 26, was at Terminal 1 to meet his wife, who had flown in from Tehran. A Ph.D. student in chemistry and biochemistry at Ohio State University, Zandian had driven through the night from Columbus, parked his car in the airport garage, and slept for two hours. But Parisa did not appear after her flight landed at 9:15 a.m. On an Iranian passport, her F2 visa had been rendered useless overnight.

Zandian had spoken to her twice on the phone, and she said she would be deported—either Monday morning or Saturday night. He spent $800 on a ticket for Saturday. He didn’t want his wife spending the weekend in the windowless detainment rooms of Kennedy Airport. Spending Saturday in the same building was as close as they’d get to an embrace.

Under Friday’s executive order, Zandian faces a choice between continuing his doctorate and seeing his wife.

Even as lawyers rushed to prepare habeas petitions for detained visitors, family members faced a pressing choice: Buy tickets for family to return immediately, increasing the chance that they might be able to acquire a visa at a later date, or fight the detention while waiting for them to be deported—a move that they were told could doom a subsequent visa application if it failed.

Sahar, an Iranian living in the U.S. who declined to give her last name, was waiting with her husband for her parents, who were visiting from Tehran. She had not seen them in more than two years. Her father was sick and needed a wheelchair for the plane. “I begged the officers just to let me see them for a minute,” she said, her eyes filling with tears. That plea was denied. Her parents, fearing the future consequences of a deportation, were returning that night.

You could see why the TV cameras were outside, at the growing crowd of protesters. People whose parents, wives and children had been suddenly imprisoned inside an airport terminal looked a lot like regular people at the airport. Anxious faces, pacing, long phone calls, requests for a phone charger. The quiet upending of American lives.

This was a crisis of rules, a drama unfolding on the bureaucratic terrain of an international airport where not even the congressmen knew what the law was, or who was being held, or when they would be freed.