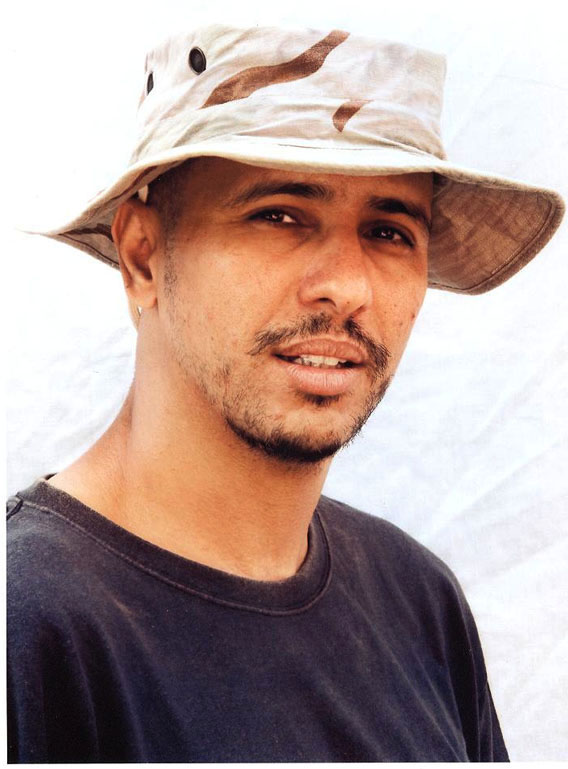

The Guantánamo Memoirs of Mohamedou Ould Slahi

He was tortured, beaten, and humiliated, and he remains in prison. Here is his story, in his own words.

Courtesy of the International Committee of the Red Cross

For nearly 11 years, Mohamedou Ould Slahi has been a prisoner in Guantánamo. In 2005, he began to write his memoirs of his time in captivity. His handwritten 466-page manuscript is a harrowing account of his detention, interrogation, and abuse. Although his abuse has been corroborated by U.S. government officials and independent investigators, Slahi tells his story with the detail and perspective that could only be known by himself and the people who have kept him captive. Following is a three-part excerpt from Slahi's declassified memoir. Until now, it has been impossible for him to tell his story. For more on the Guantánamo Memoirs, click here.

Mohamedou Ould Slahi voluntarily turned himself in for questioning to police in his native Mauritania on Nov. 20, 2001; a week later, at the behest of the U.S. government, he was placed on a rendition flight to Jordan. Slahi, who had lived in Germany and Canada, was interrogated and cleared by Jordanian intelligence of any connection to the Millennium Bomb Plot, the foiled plan of Canadian resident Ahmed Ressam to explode a bomb at Los Angeles International Airport on New Year’s Eve, 1999. Unsatisfied, on July 19, 2002 the CIA retrieved Slahi from Jordan and flew him to Bagram Air Force Base in Afghanistan.

Detainees were not allowed to talk to each other, but we enjoyed looking at each other. The punishment for talking was hanging the detainee by his hands with the feet barely touching the ground. I saw an Afghan fellow detainee who passed out a couple of times while hanging from his hands. The medics “fixed” him and hung him back up. Other detainees were luckier; they were hung for a certain time and released. Most of the detainees tried to talk while hanging, which makes the guards double their punishment.

There was a very old Afghani fellow, who reportedly was arrested to turn over his son. The guy was mentally sick; he could not stop talking because he didn’t know where he was, nor why. But the guards kept dutifully hanging him. It was so pitiful; one day one of the guards threw him on his face, and he was crying like a baby.

We were put in about six or seven big barbed-wire cells, called after the operations performed against the U.S.: “Nairobi,” “U.S.S. Cole,” “Dar es Salaam,” and so on. In each cell there was a detainee called “English,” who benevolently served as an interpreter to translate the orders to his co-detainees. Our “English” was a gentleman from Sudan named [ ? ? ? ? ?]. His English was very basic, thus he asked me secretly whether I spoke English. “No,” I replied. But as it turned out I was a Shakespeare compared to him.

Now I am sitting in front of a bunch of dead-regular U.S. citizens; my first impression, when I saw them chewing without a break: “What’s wrong with these guys, do they have to eat so much?” Most of the guards are tall, and overweight. Some of them were friendly and some very hostile. Whenever I realized that a guard [was hostile], I pretended that I understood no English. I remember one cowboy coming to me with an ugly frown on his face.

“You speak English?” he asked.

“No English,” I replied.

“We don’t like you to speak English, we want you to die slowly,” he said.

“No English,” I kept replying. I didn’t want to give him the satisfaction that his message arrived. People with hatred have always something to get off their chests, but I wasn’t ready to be that drain.

I had been living the days to follow in horror. Whenever [ ? ? ? ? ?] went past our cell, I looked away, avoiding seeing him so he doesn’t “see” me, exactly like an ostrich. I saw him torturing this other detainee. I don’t want to recount what I heard about him; I just want to tell what I saw with my eyes. It was that Afghani teenager, I would say 16 or 17 years old. [ ? ? ? ? ?] made him stand for about three days, sleepless. I felt so bad for him. Whenever he fell down, the guards came to him shouting, “No sleep for terrorists,” and made him stand again. I remember sleeping and waking up, and he stood like a tree.

On Aug. 4, 2002, Slahi was again hooded, shackled, diapered, and drugged, and put on a flight with 30 other Bagram Air Base detainees for a 36-hour journey to Guantánamo. He arrived depleted from his nine-month ordeal in Jordan and Afghanistan; official Defense Department documents record that Slahi, who stands 5-foot-7, weighed just a little over 109 pounds when he was “inprocessed” on August 5.

The shoutings of my fellow detainees woke me up in the early morning. Life was suddenly blown into [ ? ? ? ? ?]. When I came early this morning around 2 a.m., I never thought that human beings could possibly be stored in a bunch of cold boxes. I thought I was the only one, but I was wrong; my fellow detainees were only knocked out due to the harsh punishment trip they had behind them.

While the guards were serving food, we were introducing ourselves. We couldn’t see each other because of the design of the block, but we could hear the others.

“Salaam Alaikum!”

“Walaikum Salam.”

“Who are you?”

“I am from Mauritania, Palestine, Syria … Saudi Arabia …!”

“How was the trip?”

“I almost froze to death,” shouted one guy.

“I slept the whole trip,” replied [ ? ? ? ? ?].

“Why did they put the patch beneath my ear?” shouted another.

“Who was in front of me in the truck?” I asked. “He kept moving, which made the guards beat me all the way from the airport to the camp!”

“Me, too,” shouted another detainee.

We called each other with the ISN numbers we were assigned in Bagram. My number was 760. In the cell on my left was [ ? ? ? ? ? ?] from [ ? ? ? ? ? ?]. In the right cell, there was a guy from [ ? ? ? ? ? ?]. He spoke poor Arabic, and claimed to have been captured in Karachi, where he attends the university. In front of my cell they put the Sudanese next to each other.

Breakfast was modest, one boiled egg, a hard piece of bread, and something else I don’t know the name. It was my first hot meal since I left Jordan. Oh, the tea was soothing! People shouting all over the place in indistinct conversations: It was just a good feeling when everybody started to recount his story.

I considered the arrival to Cuba a blessing, and so I told my brothers, “Since you guys are not involved in crimes you need to fear nothing. I personally am going to cooperate, since nobody is going to torture me. I don’t want any of you to suffer what I suffered in Jordan.” I wrongly believed that the worst was over, and cared less about the time it would take the Americans to figure out I am not the guy they are looking for. I trusted the American justice system too much, and shared that trust with people from European countries. We all have an idea about how the democratic system works.

The other fellow detainees, for instance from the Middle East, didn’t believe it for a second and didn’t trust the American system. Their argument rested on the growing hostility of extremist Americans against the Muslims and the Arabs. With every day going by, the optimists lost ground, and the interrogation methods worsened considerably as time went by. As you shall see, those responsible in GTMO broke all the principles upon which the U.S. was built.

*

[ ? ? ? ? ?] escort team showed up at my cell. “[ ? ? ? ? ?],” said one of the MPs while holding the long chains in his hands. [ ? ? ? ? ?] is the code word for being taken to interrogation. Although I didn’t understand where I was going, I prudently followed their orders until they delivered me to the interrogator. His name was [ ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ?], wearing a U.S. army uniform. He is an [ ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ?], a man with all the paradoxes you may imagine. He spoke Arabic decently with a [ ? ? ? ? ?] accent; you can tell he grew up among [ ? ? ? ? ?] friends. [ ? ? ? ? ?] told me that he is from [ ? ? ? ? ?] and that he used to interpret for the [ ? ? ? ? ?].

I was terrified when I stepped into the room in [ ? ? ? ? ?] building, because of the CamelBak on [ ? ? ? ? ?] back, from which he was sipping. I never saw anything like that before; I thought it was a kind of tool to hook on me as a part of my interrogation. I really don’t know why I was scared, but the fact that I never saw [ ? ? ? ? ?] nor his CamelBak, nor did I expect an Army guy; all these factors contributed to my fear.

The older gentlemen who interrogated me the night before entered the room with some candies and introduced [ ? ? ? ? ?] to me. “I chose [ ? ? ? ? ?] because he speaks your language. We’re going to ask you detailed questions about you [ ? ? ? ? ?]. As to me, I am going to leave soon, but my replacement will take care of you. See you later.”

After the introduction he stepped out of the room, leaving me and [ ? ? ? ? ?] to work. [ ? ? ? ? ?] was a friendly guy; he was [ ? ? ? ? ?] in the U.S. Army who believed himself to be lucky in life. [ ? ? ? ? ?] wanted me to repeat to him again my whole story, which I’ve been repeating for the last three years over and over. I got used to interrogators asking me the same things. Before the interrogator even moves his lips I knew his questions, and as soon as he or she started to talk I turned my “tape” on. When I came to the part about Jordan, [ ? ? ? ? ?] felt very sorry!

“Those countries don’t respect human rights. They even torture people.” I was comforted because [ ? ? ? ? ?] criticized cruel methods during interrogation; that means that the Americans wouldn’t do something like that. Yes, they were not exactly following the law in Bagram, but that was in Afghanistan, and now we are in a U.S.-controlled territory.

After [ ? ? ? ? ?] finished his interrogations, he sent me back and promised to come back should new questions arise. During the session with [ ? ? ? ? ?] I asked him to use the bathroom.

“No. 1 or No. 2?” he asked. It was the first time I heard the human private business coded in numbers. In the countries I’ve been in it is not customary to ask people about their intention in the bathroom, nor do they have a code.

The team could see very obviously how sick I was; the prints of Jordan and Bagram were more than obvious. I looked like a ghost. On my second or third day in GTMO I collapsed in my cell. I was just driven to my extremes. The medics took me out of my cell; I tried to walk the way to the hospital but as soon as I left [ ? ? ? ? ?], I collapsed once more, which made the medics carry me to the clinic. I threw up so much that I was completely dehydrated. I received first aid and got an IV. The IV was terrible, they must have put in some medication I have allergy against. My mouth dried completely up, and my tongue became so heavy that I couldn’t ask for help. I gestured with hands to the corpsmen to stop dripping the fluid into my body, which they did.

Later that night the guards brought me back to my cell. I was so sick I couldn’t climb on my bed. I slept on the floor the rest of the month. The doctor prescribed me Ensure and some hypertension medicine. Every time I got my sciatic nerve crisis, the corpsmen gave me Motrin.

Although I was physically very weak, the interrogation didn’t stop. But I nonetheless was in good spirits. In the block we were singing, joking, and recounting each other stories. I also got the opportunity to learn about the star detainees such as his excellence [ ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ?]. [ ? ? ? ? ?] fed us with the latest news from the camp and the rumors. [ ? ? ? ? ?] was transferred to our block due to his “behavior.” [ ? ? ? ? ?] told us that he was tortured in Kandahar with other detainees. “They put us under the sun for a long time, we got beaten, but brothers don’t worry, here in Cuba there is no torture, the rooms are air-conditioned, and some brothers even refuse to talk unless offered food,” he said.

He was captured with four other colleagues of his in his domicile in [ ? ? ? ? ?] after midnight under the cries of his children, and was pried off his kids and his wife; exactly as it happened to his friends, who confirmed the story. I heard tons of such stories and every story made me forget the last one. I couldn’t tell whose story was more saddening. It even started to undermine my story, but the detainees were unanimous that my story was the most saddening. I personally don’t know. The German proverb says, “Wenn das Militar sich Bewegt, bliebt die Wahrheit auf der Strecke”—when the military sets itself in motion, the truth is too slow to keep up, thus it stays behind. The law of war is harsh; if there is anything good at all in a war, it is that it brings the best and the worst out of people. Some people try to use the lawlessness to hurt others, and some try to reduce the suffering to the minimum.

For his first several months in Guantánamo, Slahi was interrogated by agents from the FBI and the Navy’s Criminal Investigation Task Force. Both the FBI and CITF favored conventional, “rapport building” interrogation methods; throughout the fall, both agencies clashed repeatedly with Guantánamo’s commanders over the military’s increasingly abusive interrogations, and fought Pentagon plans for the “Special Project” interrogation of Mohammed al-Qahtani, a 50-day torture regime of extreme sleep deprivation, 20-hour-a-day interrogations, and repeated physical and sexual humiliations.

By January 2003, military interrogators were agitating to make Slahi their second “Special Project,” drawing up an interrogation plan that mirrored Qahtani’s. Declassified documents show that Slahi’s “special interrogation” began when he was transferred to an isolation cell near the end of May.

Things went more quickly than I thought. [ ? ? ? ? ?] sent me back to the block, and I told my fellow detainees about being overtaken by the torture squad.

“You are not a kid. Those torturers are not worth thinking about. Have faith in Allah,” said my next [ ? ? ? ? ?]. I really must have acted like a child all day long before the guards pried me from the population block later that day. You don’t know how terrorizing it is for a human being to be threatened with torture. One becomes literally a child. An Arabic proverb says, “Waiting on torture is worse than torture itself.” I can only confirm this proverb.

The escort team showed up at my cell: “You got to move.”

“Where?”

“Not your problem,” said the hateful [ ? ? ? ? ?] guard. But he was not very smart, for he had my destination written on his glove.

“Brother, pray for me, I am being transferred [ ? ? ? ? ?]." [ ? ? ? ? ?] was reserved by then for the worst detainees in the camp. If one got transferred [ ? ? ? ? ?] many signatures must have been provided, maybe the president of the U.S. The only people I know to have spent some time [ ? ? ? ? ?] since it was designed for torture were [ ? ? ? ? ?] al Kuwaiti and another detainee from [ ? ? ? ? ?], I don’t know the name.

In the block the recipe started. I was deprived of my comfort items, except for a thin iso-mat and a very thin, small, and worn-out blanket. I was deprived of my books, which I owned. I was deprived of my Quran. I was deprived of my soap. I was deprived of my toothpaste. I was deprived of the roll of toilet paper I had. The cell—better, the box—was cooled down so that I was shaking most of the time. I was forbidden from seeing the light of the day. Every once in a while they gave me a rec time in the night to keep me from seeing or interacting with any detainees. I was living literally in terror. I don’t remember having slept one night quietly; for the next 70 days to come I wouldn’t know the sweetness of sleeping. Interrogation for 24 hours, three and sometimes four shifts a day. I rarely got a day off.

“We know that you are a criminal.”

“What have I done?”

“You tell me, and we reduce your sentence to 30 years. Otherwise you will never see the light again. If you don’t cooperate we are going to put you in a hole and wipe your name out of our detainees database.” I was so terrified because I knew, even though he couldn’t make such decision on his own, he had the complete backup of the high government level. He didn’t speak from the air.

“I don’t care where you take me, just do it.”

When I failed to give him the answer he wanted to hear, he made me stand up, with my back bent because my hands were shackled with my feet and waist and locked to the floor. [ ? ? ? ? ?] turned the temp control all the way down, and made sure that the guards maintained me in that situation until he decided otherwise. He used to start a fuss before going to his lunch, so he kept me hurt during his lunch, which took at least two to three hours. [ ? ? ? ? ?] likes his food; he never missed his lunch. I was wondering, how could [ ? ? ? ? ?] have possibly passed the fitness test of the Army? But I realized he is in the Army for a reason.

The fact that I wasn’t allowed to see the light made me “enjoy” the short trip between my freakin’ cold cell and the interrogation room. It’s just a blessing when the warm GTMO sun hit me. I felt the life sneaking back into every inch of my body. I always had this fake happiness, though for a very short time. It’s like taking narcotics.

“How you been?” said one of the Puerto Rican escorting guards, with his weak English.

“I’m OK, thanks, and you?”

“No worry, you gonna back to your family,” he said. When he said so I couldn’t help breaking into [ ? ? ? ? ?]. Lately, I had become so vulnerable. What’s wrong with me? Just a soothing word in this ocean of agony was enough to make me cry.

[ ? ? ? ? ?] we had a complete Puerto Rican division. They were different than other Americans. They were not as vigilant and unfriendly. Sometimes they took detainees to shower [ ? ? ? ? ?]. Everybody liked them. Due to their friendly and humane approach to detainees, they got in trouble with those responsible for the camps. I can’t objectively speak about the people from Puerto Rico because I haven’t seen enough, but if you ask me have you ever seen a bad Puerto Rican? My answer would be no.

“We’re gonna talk today about [ ? ? ? ? ?],” [said] [ ? ? ? ? ?] after bribing me with a weathered metal chair.

“I have told what I know about [ ? ? ? ? ?].”

“No, that’s bullshit. Are you gonna tell us more?”

“No, I have no more to tell.” The new [ ? ? ? ? ?] pulled the metal chair away and left me on the floor.

“Talk about it, it wouldn’t hurt,” the new [ ? ? ? ? ?] said.

“No.”

“Today, we’re gonna teach you about great American sex. Get up,” said [ ? ? ? ? ?].

As soon as I stood up, the two [ ? ? ? ? ?] took off their blouses and started to talk all kinds of dirty stuff you can imagine. Both [ ? ? ? ? ?] stuck on me literally from the front, and the other older [ ? ? ? ? ?] stuck on my back, rubbing [ ? ? ? ? ?] whole body on mine. At the same time they were talking dirty to me, and playing with my sexual parts. I am saving you here from quoting the disgusting and degrading talk I had to listen to from noon or before until 10 p.m. when they turned me over to [ ? ? ? ? ?], the new character you’ll learn about later.

To be fair and honest, the [ ? ? ? ? ?] didn’t deprive me of my clothes at any time; everything happened with my uniform on. The senior [ ? ? ? ? ?] was watching everything [ ? ? ? ? ?]. I kept praying all the time.

“Stop the fuck praying. You’re having sex with American [ ? ? ? ? ?] and you’re praying? What a hypocrite you are!” said [ ? ? ? ? ?] angrily while entering the room. I refused to stop speaking my prayers. During this session I also refused to eat or to drink, although they offered me water every once in a while. I was just wishing to pass out so I didn’t have to suffer; and that was really the main reason for my hunger strike. I knew people like them don’t get impressed by a hunger strike. Of course they didn’t want me to die, but they understand there are many steps until one dies.

“You’re not gonna die, we’re gonna feed you up your ass,” said [ ? ? ? ? ?].

In July 2003, more than a month into his “special interrogation,” documents show that Slahi was interrogated for a week by a new, masked interrogator, kept in a refrigerated cell, and told he would be made to “disappear.” On Aug. 2, 2003, a military interrogator posing as an emissary from the White House visited Slahi carrying a letter saying that Slahi’s mother was in custody and would soon be transferred to Guantánamo, where the U.S government could not guarantee her safety.

“Get the motherfucker back,” shouted [ ? ? ? ? ?], a celebrity among the torture squad. He was about 6 feet tall, athletic-built, and [ ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ?]. He was aware that he was committing heavy crimes of war, thus he was ordered by his bosses to cover himself. But if there is any kind of basic justice, he would be busted through his bosses. We know their names and their ranks.

When I got to know [ ? ? ? ? ?] more and heard him speaking, I wondered how could a man as smart as he was possibly accept such a degrading job, which surely is going to haunt him the rest of his life. I later on discussed with some of my guards why they executed the order of stopping me from praying, since it is an unlawful order. “I could have, but my boss would have given me a shitty job, or transferred me to a bad place. I know I can go to hell for what I have done to you,” he said. History repeats itself: after World War II, German soldiers were not excused when they argued that they received orders.

“You’ve been giving [ ? ? ? ? ?] a hard time,” continued [ ? ? ? ? ?], while dragging me into a dark room. With the help of the guards he dropped me on the dirty floor. The room was as dark as ebony. [ ? ? ? ? ?] started playing a track very loudly. I mean very loudly. The song was, “Let the Bodies Hit the Floor.” I might never forget that song. [ ? ? ? ? ?] at the same time turned on some colored blinkers that hurt the eyes. “If you fucking fall asleep, I’m gonna hurt you,” he said. I had to listen to the song over and over until the next morning.

“Welcome to hell,” said the [ ? ? ? ? ?] guard when I stepped inside the block. I didn’t answer, and [ ? ? ? ? ?] wasn’t worth it. But I was like, “I think you deserve hell more than I do, because you’re working dutifully to go to hell!” The guards on the block actively participated in the process of torture. The [ ? ? ? ? ?] tell them what to do with the detainee once he came back to the block. I had guards banging on my cell to prevent me from sleeping. They cursed me for no reason. They repeatedly woke me. I never complained to my interrogators about that issue because I knew they planned everything with the guards.

*

“I told you, I’m gonna bring some people to help me interrogate you,” said [ ? ? ? ? ?] sitting inches away in front of me. [ ? ? ? ? ?] offered me a metal chair. The guest sat almost sticking on my knee. [ ? ? ? ? ?] started to ask me some question I don’t remember.

“Yes or no?” shouted the guest, loud beyond belief, in a show to scare me, and maybe to impress [ ? ? ? ? ?], who knows? I found his method very childish and silly. I looked at him, smiled, and said, “Neither!” The guest violently drew the chair from beneath me. I fell on the chains. Oh, it hurt.

“Stand up, motherfucker,” shouted both, almost synchronous. Then a session of torture and humiliation started. They started to ask me the questions after they made me stand up, but it was too late, because I told them a million times, “Whenever you start to torture me, I’m not gonna say a single word.” And that was always accurate, for the rest of the day, they were the only ones to talk.

[ ? ? ? ? ?] turned the air conditioning all the way down to bring me to freezing. This method had been practiced in the camp at least since August ’02. I have seen people who were exposed to the frozen room day after day such as [ ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ?], [who] told me of having suffered the same fate. [All the] Yemeni brothers had been suffering all kinds of humiliation including the frozen room. [ ? ? ? ? ?] the same way. And the list is long. The consequences of the cold room are devastating, such as [ ? ? ? ? ?], but they show up only later because it takes time until they work their way through the bones. Furthermore, the torture squad was so well trained that they had been performing perfect crimes, avoiding leaving any obvious evidence. Nothing was left to chance. They hit in predefined places. They practiced horrible methods, the aftermath of which only manifested later.

Technically, the interrogators turned the AC all the way down trying to reach 0 F, but obviously the AC is not designed to kill. In the well-isolated room the AC fought its way to 49 F, and if you are interested in math like me, that is 9.4 C—in other words very, very cold, especially for somebody who had to stay in it more than 12 hours, had no underwear, had a very thin uniform, and comes from a hot country. Somebody from Saudi Arabia cannot take as much cold as somebody from Sweden, and vice versa, when it comes to hot weather.

You may ask me, “Where were the interrogators, after installing me in the frozen room?” Actually, it’s a good question, and the answer is: First, the interrogators didn’t stay in the room, they just come for humiliation, degradation, and discouragement, or another factor of torture; after that they left and went to the monitoring room next door. Second, interrogators were dressed adequately. For instance, [ ? ? ? ? ?] was dressed like somebody entering a meat locker. In spite of that, they didn’t stay a long time with the detainees. Third, interrogators kept moving in the room, which meant blood circulation, which meant keeping themselves warm while the detainee was [ ? ? ? ? ?] all the time, on the floor, standing up for the most part. All I could do was move my feet and rub my hands. But the Marine guy stopped me from rubbing my hands by ordering a special chain that shackled my hands on my opposite hips. If I get nervous I always start to rub my hands together and write on my body, and that drove my interrogators crazy.

“What are you writing?” shouted [ ? ? ? ? ?] “Either you tell me or you stop the fuck,” but I couldn’t stop anyway, it was unintentional.

The man in [charge of] the show started to throw chairs around, and hit me with his forehead, and described me with all kinds of adjectives I don’t deserve, for no reason. The guy was nuts; he asked me about things I have no clue about, and names I never heard. “I have been in [ ? ? ? ? ?],” he said, “and you know who was our host? The president! We had a good time in the palace.”

The Marine guy asked questions and answered himself. When the man failed to impress me with all the talk and humiliation and the threat to arrest my family (since the [ ? ? ? ?] “was an obedient servant of the U.S.”), he started to hurt me more. He brought ice-cold water and soaked me all over my body. My clothes stuck on me. It was so awful, I kept shaking like a Parkinson’s patient. Technically I wasn’t able to talk anymore. The guy was stupid, he was literally executing me but in a slow way. [ ? ? ? ?] gestured to him to stop pouring water on me. I refused to eat anything; I couldn’t open my mouth anyway.

The guy was very hot, when [ ? ? ? ? ?] stopped him because he was afraid of the paperwork which would [result] in case of my death. He found another technique; namely, he brought a CD-player with booster and started to play some rap music. I didn’t really mind the music because it made me forget my pain; actually, the music was a blessing in disguise, I was trying to make sense of the words. All I understood was that the music was about love, can you believe it? Love! All I had experienced lately was hatred or the consequences thereof. “Listen to that, motherfucker!” said the guest, while closing the door violently behind him. “You’re gonna get the same shit day after day, and guess what? It’s getting worse. What you’re seeing is only the beginning,” said [ ? ? ? ? ?]. I kept praying and ignoring what they were doing.

“Oh, ALLAH, help me. … Oh, Allah, have mercy on me,” [ ? ? ? ? ?] kept mimicking my prayers, “ALLAH … ALLAH … There is no Allah. He let you down!” I smiled at how ignorant [ ? ? ? ? ?] was by talking about the Lord like that.

Between 10 and 11 p.m. [ ? ? ? ? ?] handed me over to [ ? ? ? ? ?] and gave an order to the guards to move me to his specially prepared room. It was so cold and full of pictures showing the glories of the U.S.: weapons arsenal, planes, pictures of G. Bush. “Don’t pray, you insult my country if you pray during my national hymn. We are the greatest country in the free world, and we have the smartest president of the world,” said [ ? ? ? ? ?]. For the whole night I had to listen to the U.S. hymn. I hate hymns anyway. All I can remember was the beginning, “Oh say can you see …” over and over.

Between 4 and 5 a.m. [ ? ? ? ? ?] released me just to be taken a couple of hours later by [ ? ? ? ? ?] to start the same routine over and over. The hardest step is the first, the hardest days were the first days; with every day going by I grew stronger. Meanwhile, I was the main subject of talk in the camp, although many other detainees were suffering a similar fate; I was “Criminal No. 1,” and I was appropriately treated. Sometimes, when I was in the rec yard, detainees shouted, “Be patient. Remember Allah tries the people he loves the most.” Comments like that were my only solace beside my faith in the Lord.

[Then] [ ? ? ? ? ?] crawled from behind the scene and appeared in the picture: [ ? ? ? ? ?] had told me a couple of times before [ ? ? ? ? ?] visit about a very high level government person who was going to visit me and talk to me about my family. I personally didn’t take the information negatively; I thought he was going to bring me some messages from my family, but I was wrong. It was about hurting my family. [ ? ? ? ? ?] was escalating the situation relentlessly with me.

[ ? ? ? ? ?] came around 11 a.m., escorted by [ ? ? ? ? ?] and the new [ ? ? ? ? ?]. He was brief and direct.

“My name is [ ? ? ? ? ?]. I work for [ ? ? ? ? ?]. My government is desperate to get information out of you. Do you understand?”

“Yes.”

“Can you read English?”

“Yes.”

[ ? ? ? ? ?] handed me a letter he obviously forged. The letter was from DoD and it said, basically, “Ould Slahi was involved in the Millennium attack and recruited three of the September 11 hijackers. Since Slahi has refused to cooperate, the U.S. government is going to arrest his mother and put her in a special facility.”

I read the letter. “Is that not harsh and unfair?” I said.

“I am not here to maintain justice. I am here to stop people from crashing planes into buildings in my country.”

“Then go and stop them. I have done nothing to your country,” I said.

“You have two options, either being a defendant or a witness.”

“I want neither.”

“You have no choice, and your life is going to change decidedly,” he said.

“Just do it, the sooner, the better!” I said.

* * *

In July 2003, as Slahi’s “special interrogation” continued, Guantánamo commander Maj. Gen. Geoffrey Miller added another brutal ruse to Slahi’s interrogation plan. Following days of intensive questioning, Slahi was to be forcibly removed from his cell by a team of military police in riot gear, escorted past menacing dogs, and loaded onto a helicopter, where he would be flown out over the ocean and threatened with death or rendition to a Middle Eastern country—a threat to be made all the more real by the presence of Egyptian and Jordanian interrogators on the flight. The general’s plan was subsequently revised because, as his intelligence chief later told Justice Department investigators, “Miller had decided that [the helicopter] was too difficult logistically to pull off, and that too many people on the base would have to know about it to get it done.” Instead, on Aug. 24, 2003, in accordance with the plan that Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld ultimately signed, Slahi was abducted from his cell and taken on a three-hour boat trip into the Caribbean, where he was beaten and threatened by U.S. military personnel and two Arab interrogators.

I barely finished my meal, when all of a sudden [ ? ? ? ? ?] and I heard a commotion, guards cursing loudly, “I told you, motherfucker …,” people banging the floor violently with heavy boots, dog barking, doors closed loudly. I froze in my seat. [ ? ? ? ? ?] went speechless. We were staring at each other, not knowing what was going on. My heart was pounding because I knew a detainee was going to be hurt. Yes, and the detainee was me.

Suddenly a commando team of three soldiers and a German shepherd broke into our interrogation room. [ ? ? ? ? ?] punched me violently, which made me fall face down on the floor, and the second guy kept punching me everywhere, mainly on my face and my ribs. Both were masked from head to toe.

“Motherfucker, I told you, you’re gone!” said [ ? ? ? ? ?]. His partner kept punching me without saying a word; he didn’t want to be recognized. The third man was not masked, he stayed at the door holding the dog collar, ready to release it on me.

“Who told you to do that? You’re hurting the detainee,” screamed [ ? ? ? ? ?], who was no less terrified than I was.

As to me, I couldn’t digest the situation. My first thought was, they mistook me for somebody else. My second thought was to try to look around, but one of the guards was squeezing my face against the floor. I saw the dog fighting to get loose. I saw [ ? ? ? ? ?] standing up, looking helpless at the guards working on me.

“Blindfold the motherfucker! He’s trying to look—” One of them hit me hard across the face and quickly put goggles on my eyes, earmuffs on my ears, and a small bag over my head. They tightened the chains around my ankles and my wrists; afterward I started to bleed. All I could hear was [ ? ? ? ? ?] cursing, “F-ing this and F-ing that.” I thought they were going to execute me.

The other guard dragged me out with my toes tracing the way, and threw me in a truck, which immediately took off. The beating party would last for the next three to four hours, before they turned me over to another team that would use different torture techniques.

“Stop praying, motherfucker. You’re killing people,” [ ? ? ? ? ?] said, and punched me hard on my mouth. My mouth and nose started to bleed, and my lips grew so big that I technically could not speak anymore. The colleague of [ ? ? ? ? ?] turned out to be one of my guards; [ ? ? ? ? ?] and [ ? ? ? ? ?] each took one of my sides and started to punch me and smash me against the metal of the truck. One of the guys hit me so that my breath stopped and I was choking. I felt like I was breathing through my ribs.

Did I pass out? Maybe not. All I know is that I kept noticing [ ? ? ? ? ?] several times spraying ammonia in my nose. The funny thing was, Mr. [ ? ? ? ? ?] was at the same time a “lifesaver,” as were the guards I would be dealing with for the year to come; all of them were allowed to give me medication and first aid.

After 10 to 15 minutes, the truck stopped at the beach. My escort team dragged me out of the truck and put me in a high-speed boat. [ ? ? ? ? ?] never gave me a break; they kept hitting me.

“You’re killing people,” said [ ? ? ? ? ?]. I believe he was thinking out loud: He knew he was committing the most cowardly crime in the world, torturing a helpless detainee who was completely submissive and turned himself in. [ ? ? ? ? ?] was trying to convince himself that he was doing the right thing.

Inside the boat, [ ? ? ? ? ?] made me drink salt water, I believe it was direct from the ocean. It was so nasty I threw it up. They put an object in my mouth and shouted, “Swallow, motherfucker!” I decided inside not to swallow the organ-damaging salt water, which choked me as they kept pouring the water in my mouth. “Swallow, you idiot!” I contemplated quickly, and decided for the nasty, damaging water rather than death.

[ ? ? ? ? ?] and [ ? ? ? ? ?] had been escorting me for about three hours in the high-speed boat. The goal of such trip was, first, to torture the detainee and claim that the “detainee hurt himself during transport,” and second to make the detainee believe he is being transferred to some far faraway secret prison. We detainees knew all about this; we had detainees who reported flying four hours and finding themselves in the same jail where they started. I knew from the beginning that I was going to be transferred to [ ? ? ? ? ?].

When the boat [landed], [ ? ? ? ? ?] and his colleague dragged me out and made me sit cross-legged. I was moaning from the unbearable pain.

“Uh … Uh … ALLAH. ALLAH … I told you not to fuck with us, didn’t I?” said Mr. X, mimicking me. I hoped I could stop moaning because the gentleman kept mocking me and blaspheming the Lord; however the moaning was necessary so I could breathe. “We appreciate everybody who works with us, thanks gentlemen,” said [ ? ? ? ? ?]. I recognized his voice. Although he was addressing his Arab guests, the message was addressed to me more than anybody.

It was nighttime. My blindfold didn’t keep me from feeling the bright lighting, some kind of high-watt projectors.

“We happy for zat. Maybe we take him to Egypt, he say everything,” said an Arab guy whose voice I’d never heard, with a thick Egyptian accent. I could tell the guy was in his late 20s or early 30s based on his voice, his speech, and later on his actions. His English was both poor and decidedly mispronounced.

Then I heard indistinct conversations here and there, after which the Egyptian and another guy approached. Now they’re talking directly to me in Arabic.

“What a coward! You guys ask for civil rights? You get none,” said the Egyptian.

“Somebody like this coward, it takes us only one hour in Jordan until he spits everything,” said the Jordanian. Obviously he didn’t know that I had spent eight months in Jordan and no miracle took place.

“We take him to Egypt,” said the Egyptian, addressing [ ? ? ? ? ?].

“Maybe later,” said [ ? ? ? ? ?].

When I heard Egypt, and a new rendition, my heart was pounding. I hated the endless world tour I was forcibly taking. I thought that rendition to Egypt on the spot was possible, because I knew how irritated and desperate the Americans were when it came to my case.

After all kinds of threats and degrading statements, I missed a lot of the trash talk between the Arabs and their American accomplices. At one point, I drowned in my thoughts. I felt ashamed that my people were being used for this horrible job by a government that claims to be the leader of the democratic free world, a government that preaches against dictatorship and “fights” for human rights and sends its children to die for that purpose. What a joke this government makes of its own people! What would the dead-average American think if he or she saw what his or her government is doing with someone who has done no crimes against anybody?

If people in the Arab world knew what is happening in this place, the hatred against the U.S. would be heavily watered, and the accusation that the U.S. helps and works together with dictators in our countries would be cemented. I had a feeling, or rather a hope, that these people would not go unpunished for their crimes. The situation didn’t make me hate either the Arabs or the Americans; I just felt bad for the Arabs.

After about 40 minutes, I couldn’t really tell, [ ? ? ? ? ?] instructed the Arabic team to take over. The two guys grabbed me roughly and since I couldn’t walk on my own, they dragged me on the tips of my toes to the boat. I must have been very near to the water because the trip to the boat was short. I don’t know, but either they put me in another boat or in a different seat. The seat was both hard and straight.

“Move!”

“I can’t move!”

“Move, fucker!” They gave this order and knew that I was too hurt to be able to move. After all I was bleeding from my mouth, my ankles, my wrists, and maybe my nose, I could not tell for sure. But the team wanted to maintain the factor of fear and terror.

“Sit!” said the Egyptian guy, who did most of the talking, while both were pulling me down until I hit the metal. The Egyptian sat on my right side, and the Jordanian on my left. “What’s your fucking name?” asked the Egyptian. “M-O-OH-H-M-M-EE-D-D-O-O-O-O-U!” I answered. Technically, I couldn’t speak because of my swollen lips and hurting mouth. You could tell I was completely scared. Usually I wouldn’t talk when somebody started to hurt me. This is a milestone in my interrogation history. In Jordan, when the interrogator smashed my face, I refused to talk, ignoring all his threats. You can tell I was hurt like never before, that it is not me anymore, and I will never be the same as before. A thick line was drawn between my past and my future with the first hit [ ? ? ? ? ?] did to me.

“He is like a kid,” said the Egyptian, accurately addressing his Jordanian colleague. I felt warm between them, though not for long, because with the cooperation of the American, a long trip of torture was being prepared.

They put on a kind of thick jacket, which fastened me to the chair. It was a good feeling—however there was a destroying drawback to it. My chest was so tightened that I couldn’t breathe properly. Plus, the air circulation was worse than the first trip. I didn’t know what exactly but something was definitely going wrong. “I c…a…n…t br…e…a…the!”

“Suck the air,” said the Egyptian wryly. I was literally suffocating inside the bag around my head.

The order went as follows: They stuffed the air between my clothes and me with ice cubes from my neck to my ankles, and whenever the ice melted they put in new hard ice cubes. Moreover, every once in a while, one of the guards smashed me, most of the time in the face. The ice served both for pain and for wiping out the bruises I had from that afternoon. Everything seemed to be perfectly prepared. Historically, dictators during medieval and pre-medieval times used this method to let the victim die slowly. The other method of hitting the victim while blindfolded in inconsistent intervals of time was used by Nazis during WWII. There is nothing more terrorizing than making somebody expect a smash every single heartbeat.

“I am from Hasi Matruh, where are you from?” said the Egyptian, addressing his Jordanian colleague. He was speaking as if nothing was happening. You could tell he was used to torturing people.

“I am from the south,” answered the Jordanian.

What would it be like if I landed in Egypt after about 25 hours of torture? What would the interrogation look like? [ ? ? ? ? ?], a [ ? ? ? ? ?], described to me his unlucky trip from Pakistan to Egypt. Everything I was now experiencing—ice cubes and smashing—was consistent with [ ? ? ? ? ?]'s story. So I expected electric shocks in the pool. How much power can my body, especially my heart, handle? I know something about electricity and its devastating, irreversible damage. I saw [ ? ? ? ? ?] collapsing in the block a couple of times every week with blood gushing out of his nose until it soaked his clothes. [ ? ? ? ? ?] was a martial arts trainer and athletically built.

But what if they don’t believe me? No, they would believe me, because they understand the recipe of terrorism more than the Americans and have more experience. Americans tend to widen the circle of involvement to catch the most possible number of Muslims. They always speak about the big conspiracy against the U.S. I personally had been asked who practiced the basics of the religion and sympathized with Islamic movements; no matter how moderate the movement, I had been asked to prove every detail about it. That is very amazing in a country such as the U.S., where Christian terrorist organizations such as Nazis and white supremacists have the freedom to express themselves and recruit people openly and nobody can bother them, while as a Muslim if you sympathize with the political views of an Islamic organization you’re in big trouble. Even attending the same mosque as a suspect brings big trouble. I mean this fact is clear for everybody who understands the ABCs of American policy toward the so-called Islamic terrorism.

In Arabic counties, the approach is similar to the U.S. approach to Christian organizations. As long as you are not involved in criminal acts, nobody gives you trouble. Sympathizing and even associating with Islamic organizations is not considered a crime. I know those facts firsthand because I have been dealing with both approaches for a relatively long time.

The Arab/American party was over, and the Arabs turned me over once more to the same U.S. team. They dragged me out of the boat and threw me, I would say, in the same truck as the one that afternoon. Obviously we were riding on a dirt road. “Do not move!” said [ ? ? ? ? ?] but I didn’t recognize any words anymore. I don’t think anybody beat me, but I was not conscious.

When the truck stopped, [ ? ? ? ? ?] and his strong associate towed me from the truck and dragged me over some steps. The cool air of the room hit me, we passed the room atmosphere and boom, they threw me face down on the metal floor of my new home. “Do not move, I told you not to fuck with me, motherfucker!” said [ ? ? ? ? ?], his voice trailing off. Obviously he was tired, and left right away with a promise of more actions, and so did the Arab team.

A short time after my arrival, I felt somebody taking [the hood] off my head. When the blindfold was taken off I saw a [ ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ?]. I figured he was a doctor, but why the heck is he hiding behind a mask, and why is he U.S. Army, when the Navy is taking medical care of detainees?

“If you fucking move, I’m gonna hurt you!”

I was wondering how could I possibly move, and what possible damage could I do. I was in chains, and every inch of my body was hurting. That is not a doctor, that is a human butcher! When the young man checked on me, he realized he needed more stuff. He left and soon came back with some medical stuff. I glimpsed his watch; it was about 1:30 a.m., which meant about eight hours since I was kidnapped from [ ? ? ? ? ?] camp.

The doctor started to wash the blood off my face with a soaked bandage. After that, he put me on a mattress—the only item in the stark cell—with the help of the guards. “Do not move,” said the guard, who was standing over me. The doctor wrapped many elastic belts around my chest and ribs area. After that, they made me sit.

“If you try to bite me, I’m gonna fuckin’ hurt you!” said the doctor.

I didn’t respond; they were moving me around like an object. Later they took off the chains, and some time later one of the guards threw a thin, small, and worn-out blanket on me through the bin hole, and that was everything I would have in the room. No soap, no toothbrush, no iso-mat, no Quran, nothing.

I tried to sleep, but I was kidding myself, my body was conspiring against me. It took some time until the medication started to work, then I trailed off, and only woke up when one of the guards hit my cell violently with his boot. “Get up, piece of shit!” The doctor once more gave me a bunch of medication and checked on my ribs.

“Done with the motherfucker,” said he, when he showed me his back heading toward the door. I was so shocked seeing a doctor acting like that, because I knew that at least 50 percent of medical treatment is psychological. I was like, “This is an evil place, since my only solace is this bastard doctor.”

Slahi continued to be interrogated in complete isolation through September and October. On Oct. 17, 2003, a GTMO interrogator emailed a military psychologist to report, “Slahi told me he is “hearing voices” now. … He is worried as he knows this is not normal. … Is this something that happens to people who have little external stimulus such as daylight, human interaction, etc???? Seems a little creepy.” The psychologist wrote back that “sensory deprivation can cause hallucinations, usually visual rather than auditory, but you never know. … In the dark you create things out of what little you have.”

To be honest, I can report very little about the couple of weeks that were to come because I was not in the right state of mind. I had been lying on my bed all the time, I was not able to realize my surroundings. I tried to find out the Kibla, the direction of Mecca, but there was no clue. Back in [ ? ? ? ? ?] the Kibla was indicated with an arrow in every cell. Yes, the U.S. is demonstratively showing the rest of the world how religious freedom ought to be maintained. Even the call to prayer was to be heard five times a day in [ ? ? ? ? ?], which I found positive. The U.S. always repeated that the war is not against the Islamic religion, which is very prudent because technically it is impossible to fight against a religion as big as Islam; strategically it would be a lost war.

In the secret camps, the war against the Islamic religion was more than obvious. There was not only no sign to Mecca, but ritual prayers were also forbidden. Reciting the Quran was forbidden. Quran possession was forbidden. Fasting was forbidden. Practically any Islamic related ritual is strictly forbidden. I am here not talking about hearsay, I am talking about something I experienced myself. I don’t believe that the average American is paying taxes to wage war against Islam; however, I do believe that there are people in the government who have a big problem with the Islamic religion.

They tried so hard to make me insane. For the first weeks I had no shower, no laundry, no brushing. I almost developed bugs. I hated my smell. No sleep was allowed; in order to enforce this, I was given 740-milliliter water bottles in intervals of one to two hours, depending on the mood of the guards, for 24 hours. The consequences were devastating. I couldn’t close my eyes for 10 minutes because I was sitting most of the time in the bathroom. When I later asked one of the guards, after the tension [eased], “Why this water diet? Why don’t you just make me stay awake by standing up like in [ ? ? ? ? ?]?”

“Psychologically it is devastating to make somebody stay awake on his own, without ordering him,” said [ ? ? ? ? ?]. “Believe me, you haven’t seen anything. We have put detainees naked under the shower for days, eating, pissing, and shitting in the shower!”

I started to hallucinate and hear voices as clear as crystal. I heard my family in a casual familial conversation, in which I couldn’t take part. I heard Quran readings with a heavenly voice. I heard music from my country. Later on the guards used these hallucinations and were talking with funny voices through the plumbing, encouraging me to hurt the guard and plot an escape. But I wasn’t misled by them, even though I played along.

“We heard somebody, maybe a genie,” they used to say.

“Yeah, but I ain’t listening to him,” I responded. I realized I was at the edge of losing my mind. I started to talk to myself. Although I tried as hard as I could to convince myself that I am not in Mauritania, nor am I near my family, so I could not possibly hear them speaking, I kept hearing voices constantly, day and night. Medical psychological assistance was out of the question, or really any medical assistance besides the asshole I didn’t want to see anyway. I couldn’t find a way on my own; at that moment, I didn’t know if it was day or night, but I assumed it to be night because the toilet drain was rather dark.

I gathered my strength, guessed the Kibla, the direction of Mecca, kneeled, and started to pray to God, “Please guide me. I know not what to do. I am surrounded with merciless wolves, who fear not thee.” When I was praying I burst into tears, though I suppressed my voice lest the guards hear me. You know there are always serious prayers and lazy prayers. My experience taught that [the Lord] always responds to your serious prayers.

“Sir,” I said, when I finished my prayer. One of the guards showed up after putting on his Halloween mask.

“What?” asked the guard with a dry, cold emotion.

“I want to see [ ? ? ? ? ?].

*

Confessions are like the beads of a necklace, if the first bead falls, the rest follow.

They dedicated the whole time until around 10 November 2003 for questioning me about Canada and Sept. 11; they didn’t ask me a single question about Germany, where I really had the center of gravity of my life.

Whenever they asked me about somebody in Canada I had some incriminating information about him, even if I didn’t know him. Whenever I thought about the words, “I don’t know …” I got nauseous because I remembered the words of [ ? ? ? ? ?]: “All you have to say, ‘I don’t know, I don’t remember, we’ll fuck you,’ ” or [ ? ? ? ? ?]: “We don’t want to hear your denials anymore!” So I erased the words out of my dictionary.

“We’d like you to write your answers on paper, it is too much work to keep up with your talk, and you might forget things when you talk to us,” said [ ? ? ? ? ?].

“Of course!” I responded. I was really happy with the idea because I’d rather talk to a paper than talk to him. At least the paper wouldn’t shout in my face or threaten me. After that, [ ? ? ? ? ?] drowned me in a pile of papers, which I duly filled with writings. It was good to let out my frustration and my depression. “[ ? ? ? ? ?] reads your writing with a lot of interest,” said [ ? ? ? ? ?].

“We’re gonna give you an assignment about [ ? ? ? ? ?]. He is detained in Florida and they cannot make him talk. He keeps denying everything. You better provide us a smoking gun against him,” said [ ? ? ? ? ?].

I was so sad. How rude was the guy to ask me to provide a smoking gun about somebody I hardly know?

“Oh, yes, I will,” I said. He handed me a bunch of papers and I went back in my cell. Oh, my God, I’ve been so unjust to myself and my brothers. “Nothing’s gonna happen to us … they’ll go to hell … nothing’s gonna happen to us …” I kept praying in my heart, and repeating my prayers. I took the pen and paper and wrote all kind of incriminating lies about a poor person who was seeking refuge in Canada and trying to make some money so he can start a family. Moreover, he’s handicapped. I felt so bad, and kept praying silently, “Nothing’s gonna happen to you, dear brother …” and blowing on the papers I finished. Of course it was out of the question to tell them what I know about him truthfully because [ ? ? ? ? ?] already gave me the guidelines. “[ ? ? ? ? ?] is awaiting your testimony against [ ? ? ? ? ?] with extreme interest!”

I gave the assignment to [ ? ? ? ? ?], and after the evaluation I saw [ ? ? ? ? ?] smile for the first time. “Your writing about Ahmed was very interesting, but we want you to provide more detailed information,” said he. What information did the idiot want from me? I don’t even remember what I’ve just written.

“Yes, no problem,” I said. I was very happy that God answered my prayers for [ ? ? ? ? ?] when I learned in 2005 that he was unconditionally released from custody and sent back to his country.

“He’s facing the death penalty,” [ ? ? ? ? ?] used to tell me. And I was really in no better situation. “Since I am cooperating, what are you going to do with me?” I asked [ ? ? ? ? ?]. “It depends, if you provide us a great deal of information we didn’t know, it’s going to be weighed against your sentence. For instance, the death penalty would be reduced to life, and life to 30 years,” he responded. Lord have mercy on me. What a harsh justice!

“Oh, that’s great,” I replied.

I felt bad for everybody I hurt with my false testimonies. My only solaces were, one, I didn’t hurt anyone as much as I did myself; two, I had no choice; three, I was confident that injustice will be defeated, it’s only a matter of time; four, I would not blame anybody for lying about me when he gets tortured. Ahmed was just an example. I have been writing more than thousands of pages about my friends with false information. I had to wear the suit U.S. Intel tailored for me, and that is exactly what I did.

* * *

The violent interrogation of Mohamedou Ould Slahi dragged on through the fall of 2003. He remained in complete isolation in Guantánamo’s Camp Echo. When representatives of the International Committee of the Red Cross visited the base in October, Guantánamo commander Gen. Geoffrey Miller told them Slahi was “off limits” “due to military necessity,” but insisted that Camp Echo was not being used for violent interrogations—as the ICRC delegation suspected—but as a facility where detainees could have private conversations with their attorneys. Slahi writes that he remained in “the secret place” until August 2004.

I was interrogated [ ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ?]. It was so rude to question a human being like that, especially somebody who is cooperating. They made me write names and places [ ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ?]. I was like, what ruthless people!

“Show him no mercy. Increase the pressure. Drive the hell out of him crazy,” said [ ? ? ? ? ?]. And that was exactly what the guards did. Banging on my cell to keep me awake and scared. Taking me out of my cell violently at least twice a day for cell search. Taking me outside sometimes in the middle of the night to make me do P.T. that I couldn’t do due to my health situation. Putting me facing the wall several times a day and threatening me directly and indirectly.

“You know who you are?” said [ ? ? ? ? ?].

“Uh.”

“You are a terrorist,” he continued.

“Yes, sir!”

“If we kill you once, it wouldn’t do. We must kill you 3,000 times. But instead, we feed you!”

“Yes, sir.”

In a matter of weeks I developed gray hair on the lower half of the sides of my head. In my culture, people refer to this phenomenon as the extreme result of depression.

Then, slowly but surely, guards were advised at the same time to 1) give me the opportunity to brush my teeth, 2) give me more warm meals, 3) give me more showers. [ ? ? ? ? ?] was the one who took the first steps, but I am sure there had been a meeting about it. Everybody in the team realized that I was about to lose my mind due to my psychological and physical situation. I’d been so long in segregation.

“I brought you this present,” he said, while handing me a pillow. Yes, a pillow. I received the present with a fake overwhelming happiness—not because I was dying to get a pillow, but because I took the pillow as a sign of the end of the physical torture. We have a joke back home about a man who stood bare naked on the street, and when asked, “How can I help you?” he replied, “Give me shoes.” And that is exactly what happened to me. All I needed was a pillow!!!

I had nothing in my cell. Most of the time I recited the Quran. The rest of the time I was speaking to myself and thinking about my life and the worst-case scenarios that could happen to me. I had been counting the holes of the cage I was in: There are about 4,100 holes. When they gave me a pillow as a first reward, I kept reading the tag over and over.

“Get up! Get your hands through the bin hole!” said the unfriendly-sounding guard [after a weekend without interrogation]. After they shackled me, they took me outside the building to where the [ ? ? ? ? ?] were waiting me. It was the first time for me to see the daylight. Many people take daylight for granted, but if you are forbidden to see it, you will appreciate it. The brightness made my eyes squint until they adjusted. The sun hit me mercifully with its warmth. I was terrified and shaking.

“What’s wrong with you?” asked one of the guards later on.

“I am not used to this place.”

“We brought you outside so you can see the sun. We will have more rewards like this.”

*

No matter how bad your interrogators are, a family-like relationship develops. This family relationship is just a family relationship, no more, no less, with all the advantages and disadvantages.

The family comprises the guards and your interrogators. Yes, you didn’t choose your family, nor did you grow up with it, but it is a family with all the qualities.

“I am going to leave soon,” [ ? ? ? ? ?] said a couple days before he left.

“Oh, really, why?”

“It’s about time. But the other [ ? ? ? ? ?] is gonna stay with you.” That was not exactly comforting. I was startled, and couldn’t really think of an argument to convince [ ? ? ? ? ?] to stay. But it would have been a futile argument because the transfer of military intelligence agents is not a subject of discussion.

“We’re gonna watch a movie together before I leave,” [ ? ? ? ? ?] said.

“Oh, good!” I still hadn’t digested the news yet.

[ ? ? ? ? ?] left and showed up a couple of days later with a laptop and two movies.

“You can decide which one you’d like to watch.” I picked the movie Black Hawk Down; I don’t remember the other choice. The movie was both bloody and sad. I paid more attention to the emotions of [ ? ? ? ? ?] and the guards than to the movie itself. [ ? ? ? ? ?] was rather calm. He paused the movie every once in a while to explain to me the historical background of certain scenes. The guards almost went crazy emotionally because they saw many Americans getting shot to death. But they missed the fact that the number of U.S. casualties was negligible compared to the Somalis who were attacked in their own homes. I was just wondering how narrow-minded human beings can be. When people look at one thing from one perspective, they certainly fail to get the whole picture, and that is the main reason for the majority of misunderstandings that sometimes lead to bloody confrontations.

After we finished watching the movie, [ ? ? ? ? ?] packed his computer and was ready to leave.

“Eh, by the way, you didn’t tell me when you’re going to leave!”

“I am done, you’ll not see me anymore!” I froze as if my feet were stuck on the floor. He didn’t tell me he was going to leave that soon. I thought maybe one month, three weeks, or something like that, but today? In my world, that was impossible. It was as if death was devouring some friend of yours and you just were helplessly watching him fading away.

“Oh, really, that soon. I am surprised! You didn’t tell me. Goodbye. I wish everything good for you.”

“I have to follow my orders and I leave you in good hands.” And off [ ? ? ? ? ?] went. I reluctantly went back to my cell and silently burst into tears, as if I’d lost [ ? ? ? ? ?] and not somebody whose job was to hurt me and extract information in a the-end-justifies-the-means-way. I both hated and felt sorry for myself for what happened to me.

“May I see my interrogator please?” I asked the guards, hoping that they could catch him before he reached the main gate.

“We’ll try,” said [ ? ? ? ? ?].

I retreated back in my cell, but soon [ ? ? ? ? ?] showed up at the door of my cell. “That is not fair, you know that I suffered torture and am not ready for another round.”

“You haven’t been tortured. You must trust my government. As long as you’re telling the truth, nothing bad is gonna happen to you!” Of course [ ? ? ? ? ?] meant The Truth as it’s officially defined; I didn’t want to argue with [ ? ? ? ? ?] about anything.

“I just don’t want to start everything over with new interrogators,” I said.

“It’s not gonna happen,” [ ? ? ? ? ?] said. “Besides that, you can write me. I promise I’ll answer every email of yours,” he continued.

“No, I will not write you,” I said.

“OK,” [ ? ? ? ? ?] said.

“Are you all right?” [ ? ? ? ? ?] asked.

“I am not, but you may leave.”

“I am not leaving until you assure me everything’s all right,” [ ? ? ? ? ?] said.

“I said what I had to say. Have a good trip. May Allah guide you. I’ll be just fine.”

“I am sure you will. It will take at most a week and you’ll forget me.” I didn’t speak after that, instead I went back and laid myself down. [ ? ? ? ? ?] stayed a couple of minutes, repeating, “I am not leaving until you assure me everything is all right.”

“I heard yesterday’s goodbye was very emotional. I never thought of you this way,” [ ? ? ? ? ?] said the next day. “Would you describe yourself as a criminal?”

I prudently answered, “To an extent.” I didn’t want to fall in any possible trap, even though I felt that he honestly and innocently asked the question when he realized that his evil theories about me were null.

“All the evil questions are gone,” [ ? ? ? ? ?] said.

“I won’t miss them,” I said.

Today [ ? ? ? ? ?] had come to give me a haircut. It was about time! One of the measures of my punishment was to deprive me from any hygienic shaves, teeth brushing, or haircut. Today was a big day; they brought a masked barber. Though scary looking, he did the job.

*

Although the rest of the world didn’t have a clue where the U.S. government was incarcerating me, I knew since Day 1 where I was, thanks to God and the clumsiness of the [ ? ? ? ? ?]. During my incarceration in the secret place, from August 2003 to August 2004, [ ? ? ? ? ?] let slip some words giving away the location. “When I was in [ ? ? ? ? ?],” I said.

“Over there?” he said, gesturing with his fingers in the direction of [ ? ? ? ? ?]. He rapidly took his hand back and continued his conversation, but it was too late to take it back. Another time during [ ? ? ? ? ?]'s visit, he said, “Here in GTMO … uh, I mean in the Caribbean …” When everybody gave him a startled look, he tried to repair the irreparable.

“You know you are in one of the Caribbean islands?”

“Really?”

“Yes, you are.” I always acted as if I hadn’t known any clues about my whereabouts. Guards had been trying to figure out my knowledge about the place, and repeatedly commented that I was “in the middle of nowhere.” But I always responded, “All I know, I am being detained by the DoD and the place doesn’t matter, does it?”

[Finally] [ ? ? ? ? ?] came to me, “I have to inform you, against the will of many members in our team, that you are in GTMO. You’ve been honest with us and we owe you the same.” I acted as if this was new information. But I was, at the same time, happy because it meant many things to me, to be told where I am. At the time of writing these lines I am sitting in the same cell, but I don’t have to act ignorantly about where I am, and that is a good thing.

Shortly after that the International Committee of the Red Cross was allowed to visit after a long fight with the government. It was very odd to the ICRC that I had all of a sudden disappeared from the camp as if the earth had swallowed me. All attempts of the ICRC to see me or just to know where I was were thoroughly flushed down the tube. The ICRC has no real pressure on the U.S. government; ICRC tries, but the U.S. government doesn’t change its path, even an inch. If they let the ICRC see a detainee, that means the operation against that detainee is over.

Nevertheless, I was happy when I saw [ ? ? ? ? ?] and his colleagues in around September 2004, and so were they. The ICRC was very worried about my situation. They couldn’t come to me when I needed them the most, but I cannot blame them, they certainly tried. [ ? ? ? ? ?] categorically refused to give the ICRC access to me.

[ ? ? ? ? ?] tried to get me talking about the time they couldn’t have access to me. “We have an idea because we talked to other detainees who were subject to abuse, but we need you to talk, so we can help stop further acts of abuse. We cannot act if you don’t tell us what happened to you.”

“I am sorry! I am only interested in sending and receiving mail, and am grateful that you’re helping me in doing so.” [ ? ? ? ? ?] brought a very high level ICRC [ ? ? ? ? ?] from Switzerland, who had been working on my case. [ ? ? ? ? ?] tried to get me talking, but to no avail. “We understand your worries. All we’re worried about is your well-being, and respect your decision.”

We detainees know that meetings with the ICRC are monitored. Some detainees were confronted with statements they made to the ICRC and there was no way for the [ ? ? ? ? ?] to know them unless the meetings were monitored. Many detainees refused after that to talk to the ICRC and suspected them to be interrogators disguised in ICRC clothes. I know some interrogators who presented themselves as private journalists. But to me that was very naive; for a detainee to believe such a thing and mistake a journalist for an interrogator, he must be an idiot, and there are better methods to get an idiot talking. Such mischievous practices led to tensions between detainees and the ICRC. ICRC people were cursed and spit on.

However, in the summer of 2005, I voluntarily confessed to [ ? ? ? ? ?] a bland rendition of the abuse I had been subject to. [ ? ? ? ? ?] asked whether or not he should share the information with the [ ? ? ? ? ?] and I answered positively.

“I was afraid of telling you the story because of possible retaliation. But since [ ? ? ? ? ?] was here the other day virtually threatening me; I don’t seem to have anything to lose.”

The ICRC was not the first to learn of Slahi’s ordeal. In late 2003, the Marine lawyer assigned to prosecute Slahi before the military commissions started to wonder why the prisoner had suddenly become so “prolific.” Working with an investigator from the U.S. Navy’s Criminal Investigation Task Force, Lt. Col. Stuart Couch pieced together the circumstances of Slahi’s interrogation and concluded that he had been tortured. Couch then refused to prosecute Slahi’s case, citing his belief as an evangelical Christian in “the dignity of every human being.” (See sidebar interview with Col. Morris Davis, former chief prosecutor of the Guantánamo Military Commissions.)

By 2005, Slahi’s situation had changed completely. Since then, he has been granted unusual privileges, living, as the Washington Post reported in 2010, with one other detainee in a fenced-in compound where they are allowed to garden, write, and paint.

The guards wanted to be baptized with names of characters in the show Star Wars.

“From now on we are the [ ? ? ? ? ?] and that is what you call us. Your name is Pillow,” said [ ? ? ? ? ?]. I, later on, learned that [ ? ? ? ? ?] are sort of Good Guys who fight against the Forces of Evil. For the time being, I represented the Forces of Evil and the guards the Good Guys.

[ ? ? ? ? ?] was in his early 40s, married with children, small but athletically built. He spent some time working in the [ ? ? ? ? ?], then [ ? ? ? ? ?] ended up doing a special mission for the [ ? ? ? ? ?]. “I’ve been working [ ? ? ? ? ?],” he told me.

“Your job is done. I am broken,” I answered.

“Don’t ask me anything. If you want to ask for something, ask your interrogator.”

“I got you,” I said. It sounds confusing or even contradictory but although [ ? ? ? ? ?] is a rough guy, he is humane. So to say, his bark is worse than his bite. [ ? ? ? ? ?] understands what many guards don’t understand: If you talk and tell your interrogators what they wanted to hear, you should be relieved. But many of the other nitwits kept doubling pressure on me, just for the sake of it.

“My job is to make you see the light,” said [ ? ? ? ? ?], addressing me for the first time while watching me eat my meals. Guards were not allowed to talk to me or each other. I couldn’t talk to them either. I could say only, “Yes, sir, no sir, I need medics, I need interrogators.” But [ ? ? ? ? ?] is not a by-the-book guy; he thinks more than any other guard and his goal is to make his country victorious. The means don’t matter.

“Yes, sir,” I answered, without even understanding what he meant. I thought about the literal sense of the light I haven’t seen for a long time, and believed he wanted to get me cooperating so I can see the daylight. But [ ? ? ? ? ?] meant the figurative sense. [ ? ? ? ? ?] always yelled at me and scared me, but he never hit me. He illegally interrogated me several times, and that was why I called him [ ? ? ? ? ?]; [ ? ? ? ? ?] wanted me to confess to many wild theories he heard the interrogators talking about. Furthermore, he wanted to gather knowledge about terrorism and extremism. I think his dream in life is to become an interrogator. What a hell of a dream.

“You are my enemy,” he said.

“Yes, sir.”

“So let’s talk as enemy to enemy,” [ ? ? ? ? ?] said. He opened my cell and offered me a chair. [ ? ? ? ? ?] did the talking for the most part. He was talking about how great the U.S. is, and how powerful; America is this, America is that … We Americans are so and so …” I was only wondering and shaking lightly. And every once in a while I confirmed that I was paying attention, “Yes, sir … Really … Oh, I didn’t know … You’re right … I know …”

During our conversations, he sneakily tried to make me admit to things I haven’t really done. “What was your role in September 11?”

“I didn’t participate in September 11.”

“Bullshit!” he screamed madly. I realized it would be no good for my life to look innocent, at least for the time being.

Then I said, “I was working for AQ in Radio Telecom.”

He seemed to be happier with a lie. “What was your rank?” he dug.

“I would be a lieutenant.”

I both hated and liked when he was on duty. I hated him interrogating me, but I liked him giving me more food and new uniforms. He started to give me lessons and made me practice them the hard way. The lessons were proverbs and made-up phrases he wanted me to memorize and practice in my life. I still do remember the following lesson: “1) Think before you act. 2) Do not mistake kindness for weakness … etc.” Whenever [ ? ? ? ? ?] judged me to have broken one of the lessons, he took me out of my cell and strewed all my belongings all over the place. After that, [ ? ? ? ? ?] asked me to put everything back in no time. I always failed to organize my stuff, but he only made me do it several times, after which I miraculously put my stuff back in time.

My relationship with [ ? ? ? ? ?] developed positively with every day that went by, and henceforth with the rest of the guards because they regarded him highly.

“Fuck it! If I look at Pillow I don’t think he is a terrorist, I think he is an old friend of mine, and enjoy playing games with him,” he said to the other guards.

I felt somewhat relaxed and gained some self-confidence. Now, the guards discovered in me the humorous guy and used their time with me for entertainment. They started to make me repair their DVD players and PCs; in return I was allowed to watch a movie. [ ? ? ? ? ?] didn’t exactly have the most recent PC model, and when [ ? ? ? ? ?] asked me whether I have seen [ ? ? ? ? ?] PC, I said, “You mean the museum piece that [ ? ? ? ? ?] has?” [ ? ? ? ? ?] laughed hard and said “[ ? ? ? ? ?] better not hear what you said.”

“Don’t tell him.”

We slowly but surely became a society and started to gossip about interrogators and call them names. In the mean time, [ ? ? ? ? ?] taught me the rules of chess. Before the prison, I didn’t know the difference between a pawn and the rear end of a knight, nor was I really a big gamer. I find in chess a very interesting game, especially the fact that a prisoner has total control over his pieces, giving him some confidence back. When I started playing, I played very aggressively in order to let out my frustration. [ ? ? ? ? ?] was really not very good at playing chess, but he was my first mentor and he beat me in my first game ever. But the next game was mine, and so were all the following games.

Chess is a game of strategy, art, and mathematics. It takes deep thinking, and there is no luck involved. You get rewarded or punished for your actions, your moves. [ ? ? ? ? ?] brought me a chessboard so I could play against myself. When the guards noticed my chessboard, they wanted to play me. When they started to play me, they always won. The strongest among the guards was [ ? ? ? ? ?]. He taught me how to control the center. Moreover, [ ? ? ? ? ?] brought me some literature, which helped decidedly in honing my skills. After that the guards had no chance to defeat me.

“That is not the way I taught you to play chess,” commented [ ? ? ? ? ?] angrily when I won the game.

“What should I do?”

“You should build a strategy, and organize your attack! That’s why the fucking Arabs never succeed.”

“Why don’t you just play the board?” I wondered.

“Chess is not just a game,” he said.

“Just imagine you’re playing against a computer!”

“Do I look like a computer to you?”

“No.”

The next game I tried to build the strategy in order to let [ ? ? ? ? ?] win.

“Now you understand how chess must be played,” he commented. I knew [ ? ? ? ? ?] had issues dealing with defeat, thus I didn’t enjoy playing him because I didn’t feel comfortable practicing my newly acquired knowledge. [ ? ? ? ? ?] believes there are two kinds of people, white Americans and the rest of the world. White Americans are smart and better than anybody. I always tried to explain things to him by saying, for instance, “If I were you … or … If you were me,” but he got angry and said, “Don’t you ever dare compare me with you or compare any American with you.” I was shocked then, but I did as he said. After all, I didn’t have to compare myself with anybody. [ ? ? ? ? ?] hates the rest of the world, especially the Arabs, Jews, French, Cubans, and others. The only other country he mentioned positively was England.

After one game of chess with him, he flipped the board.

“Fuck your nigger chess, this is Jewish chess!” he said.

“Do you have something against black people?” I asked.

“Nigger’s not black, nigger means stupid,” he argued.

We had discussions like that, but we had only one black guard who had no say, and when he worked with [ ? ? ? ? ?] they never interacted. [ ? ? ? ? ?] resented him. [ ? ? ? ? ?] has a very strong personality, dominant, authoritarian, patriarchal, and arrogant.

“My wife calls me Asshole,” he proudly told me.

*