To Be Black in America

-

Courtesy Rubell Family Collection, Miami.

Courtesy Rubell Family Collection, Miami.Related: The Story Behind This Exhibit

One Day and Back Then (Standing), by Xaviera Simmons, 2007

“I look a lot at the history of photography and painting and how different figures are placed in them,” says Simmons, the figure in this photo. She attempts to complicate traditional images of idyllic “Americana [and] the American landscape” by injecting different characters into her scenes of the sublime. Simmons won’t comment directly on what she intended to say with this work, but Corcoran curator Sarah Newman gives it a shot: “To me it seems to [invoke] the agricultural history of the South.”

-

Photograph courtesy Rubell Family Collection, Miami.

Photograph courtesy Rubell Family Collection, Miami.Soundsuit, by Nick Cave, 2008

Cave, a trained dancer, created this suit to be worn as a performance costume. He also designed four others, made of fabric, fiberglass, metal, and sequins, in the collection. “The suits have connections to African ceremonial dance and Mardi Gras costumes,” says Newman, who isn’t sure whether this particular one has been danced in before. “To me they look like alien visitors, they’re such strange things.”

-

Photograph courtesy Rubell Family Collection, Miami.

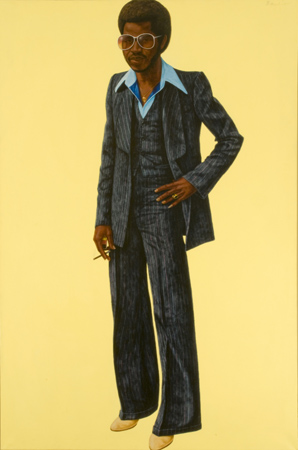

Photograph courtesy Rubell Family Collection, Miami.Noir, by Barkley L. Hendricks, 1978

Hendricks paints portraits of people he knows or people he meets while traveling. This one, Newman says, represents an iconic 1970s vision of cool. Back then, “it was so much about the clothing, the posture, and how various surface attributes made up the person,” she says. “It helped form a vision of black identity.”

-

Courtesy Rubell Family Collection, Miami.

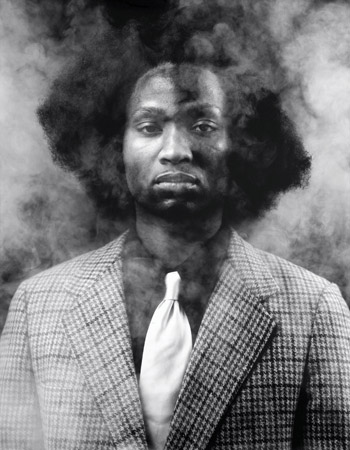

Courtesy Rubell Family Collection, Miami.The New Negro Escapist Social and Athletic Club (Thurgood), by Rashid Johnson, 2008

This image is one in a series depicting the members of a fictional secret intellectual society. This man is supposed to be Thurgood Marshall, the first black Supreme Court justice. But he’s posed in a way that references abolition leader and statesman Frederick Douglass, Newman says. She’s not sure what Johnson intended with the juxtaposition of references: “It puzzles me, this one,” she says. “To me, it also has the feel of a 1920s portrait, so it has all of these layers of time.”

-

Courtesy Rubell Family Collection, Miami.

Courtesy Rubell Family Collection, Miami.Basketball and Chain, by Hank Willis Thomas, 2003

Hank Willis Thomas’ work is inspired by the way advertising is meant to infiltrate the consciousness of black people. Here, he equates the way black bodies are used to sell products with slavery.

-

Courtesy Rubell Family Collection, Miami.

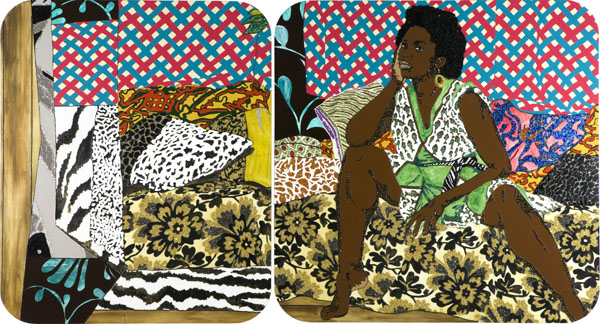

Courtesy Rubell Family Collection, Miami.Baby I Am Ready Now, by Mickalene Thomas, 2007

Mickalene Thomas often depicts modern black women with a 1970s vibe because the women of that era “are models for strong black women,” Newman points out. You can’t tell from the picture, but this painting is adorned with rhinestones.

-

Courtesy Rubell Family Collection, Miami.

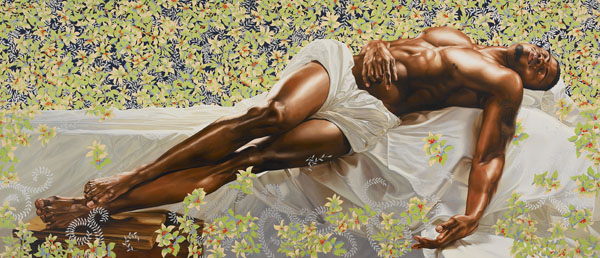

Courtesy Rubell Family Collection, Miami.Sleep, by Kehinde Wiley, 2008

As a child, Wiley grew up visiting museums and lamenting the dearth of black men in Western paintings. Now, he takes seminal works and inserts contemporary black men into them. This image, for example, is based on Jean-Bernard Restout’s 1771 painting Somnus, the Latin word for sleep.

-

Courtesy Rubell Family Collection, Miami.

Courtesy Rubell Family Collection, Miami.Pygmalion, by Robert Colescott, 1987

Colescott’s paintings “are kind of a poke in the eye to standard accounts of history,” explains Newman. This one is a take on the myth Pygmalion, an account of an artist who falls in love with his own creation (a sculpture that comes to life). (My Fair Lady, for example, is a modern Pygmalion tale.) This image satirizes the female makeover (think Eliza Doolittle)—specifically, the tricks black women use to attain a white standard of beauty.

Related: The Story Behind This Exhibit