The Magnificent Ambersons

Orson Welles' original version may be lost to history, but even the compromised studio cut is a masterpiece—and it's finally on DVD.

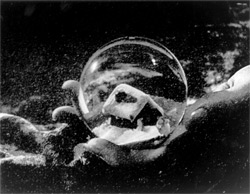

The closest thing American cinema has to a holy grail, the original cut of Orson Welles' The Magnificent Ambersons has long been the object of fevered cinephilic speculation. For years it was rumored to be collecting dust on a shelf in some Hollywood warehouse, waiting to be discovered. Another theory had it squirreled away in a Brazilian film office, site of the last time Welles ever looked at the cut. The likeliest explanation remains the one film buffs refuse to believe: that the mythical original cut of Welles' masterpiece is just that—a myth—the film cans barnacled at the bottom of the Pacific, dumped by a regime of philistines at RKO Pictures.

We dream of the movie we almost had; but what of the movie that we ended up getting? In July 1942, RKO released an 88-minute-long Ambersons as part of a double bill with something called Mexican Spitfire Sees a Ghost. This version was a drastic re-edit of Welles' cut, which played disastrously to preview audiences, and featured footage shot in Welles' absence, including an anomalous, upbeat ending. Where was the director? With America entering the war, Welles had been recruited by the State Department to make a movie promoting pan-American relations. He accepted the assignment and left for Brazil in February 1942, planning to oversee his picture's editing from afar. But leaving during post-production proved to be a mistake. The studio pried the picture away from Welles and butchered it. Ambersons eventually bombed and all but inaugurated Welles' exile from Hollywood.

But even in mutilated form, Ambersons retained its magnificence. Hollywood cheered its failure—studios hated the parvenu from New York who dared to change the way movies were made—but reviewers hailed the movie, and the Academy gave Ambersons a best picture nomination. In the years that followed, critics kept its reputation alive. In 1972, it ranked No. 8 on Sight & Sound's decadal critics' poll of the greatest films of all time. But the movie never was enshrined in the popular canon. And indeed, critics may be starting to forget, too: It hasn't appeared in the Sight & Sound poll since 1982. It's only fitting that when it finally makes its U.S. DVD debut this week, Ambersons comes packaged as an afterthought: as a bonus disc to the 70th-anniversary Blu-ray release of Citizen Kane.

In the wake of that terrific debut, the greatest in film history, Welles confronted a dilemma: What to do for a follow-up? As was his wont, Welles juggled several projects: On top of his radio commitments, he mulled making an omnibus film called It's All True that ranged from bull-fighting to immigration to jazz; a dark thriller based on Eric Ambler's bestseller Journey Into Fear; and an adaptation of Booth Tarkington's 1918 Pulitzer Prize-winner The Magnificent Ambersons.

The last one eventually became Welles' and RKO's choice as the worthy follow-up to Kane. Tarkington's novel tells the story of a wealthy family who preside over their small midland town like benevolent lords—except for one. The sun around which everyone revolves is George Amberson Minafer (Tim Holt), the family's only child and a town terror. Spoiled rotten by his mother, Isabel (Dolores Costello), George's horridness gives the book its forward motion: It is the wait for his overdue "comeuppance"—a word Tarkington lingers over lovingly—that impels the story.

Into George's complacent existence enters Eugene Morgan (Joseph Cotten, terrific as always), his mother's old flame. * An inventor working on a "horseless carriage," Eugene left town 18 years earlier, after Isabel broke off their engagement. After George's father passes, Eugene and his daughter, Lucy (Anne Baxter), become a constant presence at the mansion. George falls for Lucy, but he makes a nemesis of Eugene, who embodies all that George hates—a self-made success, harbinger of the modern, and rival for his mother's love.

At first glance, Tarkington's novel seems an odd choice for Welles. What could possibly have drawn him to this somber family saga? But after the razzle-dazzle of Citizen Kane, one can imagine Welles seeking a grown-up project shrouded in gravitas. With its pedigree and seriousness, Ambersons must have seemed a tantalizing opportunity for a director eager to be known as something more than a showman.

If Kane revels in the glories of artifice, Ambersons uses dazzling technique to get at something deeper. Welles the virtuoso is still behind the camera, but there is little of the childlike glee found in Kane's flourishes. Nothing in Kane matches the jarring intensity of the scenes of domestic strife in Ambersons. Georgie—as everyone takes to calling him—is always hectoring others; his Aunt Fanny, an old maid who pines for Eugene, seems perpetually on the brink of hysterics. Played by Agnes Moorehead in one of the great wild-eyed performances in movies, Fanny's jousts with her teasing, obnoxious nephew explode the brittle placidity of the decaying mansion. As Pauline Kael put it, the bickering sounded like "arguments overheard from childhood, with so many overtones they were almost mythic."

Released months after the bombing of Pearl Harbor, The Magnificent Ambersons couldn't help but alienate a movie-going public in search of escape and sentimentality. Such a dismal portrait of the American family—and in this our time of need! But it wasn't just the family that Ambersons dissected. By dismantling something so seemingly permanent—the Ambersons' magnificence—the movie was a haunting reminder of our essential condition: how time engulfs us all. One of the movie's most celebrated scenes conveys the theme succinctly. Reeling from his daughter's death and facing his own, the Ambersons' patriarch (the wonderful Richard Bennett) thinks about all that he has built—and confronts the smallness of human striving.

Indeed, if Kane was a young man's movie about a young country, Ambersons is an old man's dirge about an old country. It's a prodigious feat of ventriloquism by Welles, 26 at the time of its making. But that's not to say it's a detached film—far from it. At its heart, The Magnificent Ambersons is a movie about nostalgia for a bygone world, a nostalgia Welles, who romanticized his Wisconsin childhood, felt deeply. (He even made the unproven claim that Tarkington, a family friend, based the character of Eugene on his own father.) The most joyful scene in the movie is a sleigh ride the Ambersons and the Morgans take on a winter morning. It is Rosebud revisited and amplified.

Perhaps another thing that drew Welles to the material was its moral complexity. Tarkington's book was no simple wallow in nostalgia or mindless critique of progress. The author complicates our allegiances throughout. Yes, Eugene is a decent and likable man—but he also represents the industrialization that proves the undoing of small town America.And yes, Georgie is unbearable—but his yearning for a simpler time is one that we all share. That tangle of sympathies and resentments makes Ambersons an unusually rich experience. When George finally gets his comeuppance, it hardly feels like a vindication—and it yields one of the most haunting passages in Welles' oeuvre.

It's a shame that the harrowing and crepuscular movie that Welles made builds up to a fraudulent ending. Struck down by an accident, Georgie ends up in the hospital. There Eugene, Lucy, Fanny, and George reunite after years of estrangement. "He's going to be all right!" Eugene chirps after coming out of Georgie's room, slapping false uplift on the film. Welles' original screenplay ended quite differently, with Eugene visiting Fanny at the boarding house where she lives. As Welles told Peter Bogdanovich, the ending showed that "there's just nothing left between them at all. Everything is over—her feelings and her world and his world. … The end of the communication between people, as well as the end of an era." Reportedly Welles' favorite scene in the movie, the original ending never stood a chance with preview audiences and studio executives. (The irony here is that Welles' original ending was actually his most notable departure from the novel. The reshot ending that mars the picture was pretty close to Tarkington's, with its redemptive nonsense. Welles knew better than Tarkington how to end the Ambersons' saga.)

And so it was that The Magnificent Ambersons was taken away from Welles. Granted, it wasn't too hard to do that—Welles' decision to edit in absentia was a mistake, especially considering his declining clout at the studio. Some have therefore pinned the blame for Ambersons' fate on the undisciplined, distracted Welles. But to do so ignores what actually happened. After all, if the Japanese hadn't attacked Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941, and the U.S. hadn't entered the war, Welles would have remained at home throughout post-production. Moreover, one could hardly blame Welles for thinking he could finish the movie his way despite being away. Part of the plan for the film was for editor Robert Wise to travel to Rio with the print to work side by side with Welles—a plan that never panned out when Wise was prohibited from traveling because of wartime travel restrictions. Seen in this context, the beginning of Welles' end—and the legend of Ambersons—could be traced back to that date that will live in infamy.

Welles never recovered from the debacle. "They destroyed Ambersons, and it destroyed me," he would claim. The decades that followed saw him scraping by, piecing together compromised, jury-rigged productions as a Hollywood pariah. And what of that original version? Years later, Welles told Bogdanovich, "It was a much better picture than Kane—if they'd just left it as it was." Maybe, maybe not. Perhaps Welles romanticized that version too much—after all, his own frantic, lengthy cables from Rio revealed a director willing to make other drastic (and damaging) cuts.

And our yearning for the lost version has over the years claimed a casualty: the movie itself. Welles may have felt it destroyed, but the Ambersons he left us doesn't merit disowning. Unlike anything the era produced, The Magnificent Ambersons, the one we have, is a diminished masterpiece, but a masterpiece nonetheless—still beautiful despite its wounds, and defiant despite our dreams of its ideal self.

Correction, Sept. 15, 2011: This article originally misspelled Joseph Cotten's last name. (Return to the corrected sentence.)