The Actual World

“Mount Thoreau” and the naming of things in the wilderness.

Photo by Christopher Woodcock

Early on a September morning, we drove through hard rain over Donner Pass. In Reno the skies cleared, and we headed south on Highway 395, which runs under the eastern wall of the Sierra Nevada, one of the greatest escarpments on Earth. Paul Park, Gary Snyder, and I were on our way to a trailhead called North Lake, west of Bishop, California. The plan was to rendezvous late that afternoon at a high Sierra lake and camp there that night. Then the next day some dozen of us would ascend a peak and name it “Mount Thoreau.”

Question: Why do you want to climb Mount Thoreau?

Answer: Because it isn’t there.

* * *

In the Sierra Nevada there are some Native American names left, like Tuolumne and Yosemite, and many more of early white settlers: Mount Tom, Dicks Peak, Harry Birch Springs. Also wives and girlfriends. There are some good names from the years of exploration: the Enchanted Gorge, draining the Ionian Basin between Mounts Scylla and Charybdis; the Gorge of Despair; the Inconsolable Range. Famous 19th-century scientists are well-represented, including Darwin, Wallace, Huxley, Tyndall, and others. The robber barons have their peaks, too.

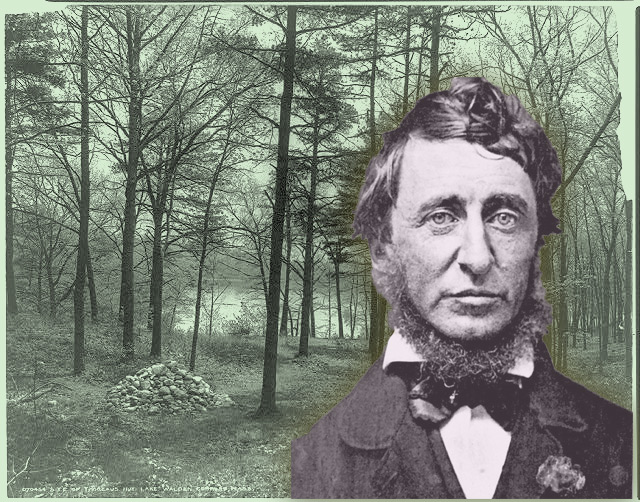

But nothing up there is named after Henry David Thoreau, the great American nature writer, the man whose books inspired John Muir and helped create the preservation movement that saved the Sierra Nevada as wilderness. This seemed an oversight, a mistake, a little crime. And an opportunity.

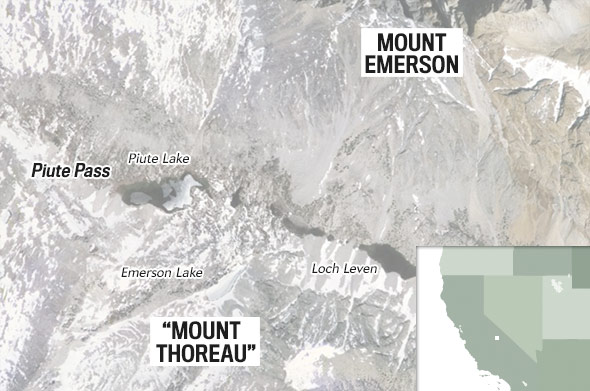

Because there is already a Mount Emerson up there, named by John Muir himself, after a trip to the area in 1873. It stands on the north wall of Piute Canyon: a big gray pyramid, reaching 13,204 feet above sea level. And across Piute Canyon from it there stands another big peak, unnamed. On the maps it’s marked 12,691. If named after Thoreau, the two peaks would then form a gateway, like Scylla and Charybdis, through which hundreds of hikers would pass every year. Peak 12,691 is somewhat lower than Mount Emerson, but much more gnarly and interesting; the two peaks have much the same relationship that Emerson and Thoreau had, not just in size and aspect but in position, being close to each other but separated by a huge gulf of air. It was just like that in Concord.

Image from Google Earth. Map from iStock.

* * *

The truth is, you can’t just go naming things in the wilderness. The Wilderness Act of 1964 states that namelessness is an aspect of wilderness, and the U.S. Geological Survey’s Board on Geographic Names has codified that opinion. Procedures must be followed. A recent bill in Congress, for instance, called for the Sierra’s North Palisade to be renamed Brower Palisade. Both California senators backed it, but there was staunch opposition, both from those opposed to David Brower’s environmentalism and from those who dislike the idea of a prominent peak changing its name. (The bill died in committee.) In another case, a Sierra peak was recently named for the late gold medal skier and conservationist Andrea Lawrence. This was possible because she lived near the mountain and was of local significance, criteria listed in the USGS naming process. It was appropriate, a lot of people worked hard for it, and President Obama signed the bill making it happen. Very good. But naming a California peak after a Massachusetts writer, 150 years after his death? No.

Still, people do like to name things, so it keeps happening, law or no law. Sierra guidebooks include scores of new names, and most of the time, as in R.J. Secor’s excellent The High Sierra, quotation marks signify the names are new. But it’s not just a matter of guidebooks. In 1996, a ranger named Randy Morgenson died in the backcountry; now the peak west of Mount Russell is being called “Mount Randy Morgenson,” a really fine memorial. Another example: The final peak of the long ridge above Evolution Basin is called Mount Darwin, and the next peak down is Mount Mendel; now the peak below Mendel has been dubbed “Mount Stephen Jay Gould.” That’s a nice tribute, also a kind of visual joke illustrating the lines of intellectual influence.

From left, photos by Joe Holtz and Kim Stanley Robinson

The Internet spreads these informal names, and quotation marks are almost always included, to indicate they are not USGS-approved. Maybe someday they will be made official, but there’s no hurry. The quotation marks have a friendly look, suggesting that people are keeping their hands in the game, as they always have.

So it was in that spirit, especially in the spirit of “Mount Stephen Jay Gould,” which is more of an intellectual tribute than a personal memorial, that we were gathering to name Peak 12,691 “Mount Thoreau.”

* * *

As we drove south on 395, we passed the ridge that marks the northern border of Yosemite National Park. Here, in the autumn of 1955, Gary drove Jack Kerouac to climb Matterhorn Peak, as Kerouac later described in his novel The Dharma Bums.

The Sierra Club has placed aluminum summit register boxes on many Sierra peaks, and many others have impromptu containers like tackle boxes, Band-Aid boxes, rusty tin cans, and the like. The pages inside these boxes are always covered by names, dates, and lots of exclamation points. But I told Gary and Paul that I had never seen one so stuffed with slips of paper, signed by such an international crowd, as the one I saw atop Matterhorn Peak in 1999: God bless you Jack Kerouac you are the greatest ever, or Thank you Gary Snyder we love you. Sitting on that peak reading them and looking at the immense view, I had been really pleased to think this was a literary monument in the California style, not a statue in a square or a trophy bestowed by a carefully selected jury, but a thing in the wind, created by readers making a pilgrimage.

We made it to the North Lake car campground around 3 and, leaving Gary there, hiked through the shadows of the late afternoon forest and the cool, thin air and across the granite confusion of the Wonder Lakes Basin. All Sierra basins began as the headwaters of glaciers, so they are generally ringed by horseshoe-shaped ridges, open where the ice flowed out and down. Under the ice, the floors of these basins had been sheared and plucked along crack systems in the granite, creating watercourses very unlike the branching shapes of those in softer ground. The result is frequently a giant rock maze, lightly grown over by patches of trees, where you can’t see or hear very far; so it was here.

Nevertheless, after about an hour of bashing upstream, we ran into the earlier groups, who were together at a pond that was not our prearranged rendezvous lake but had better campsites. It was 5:30 p.m. We were about 2 miles distant and 2,000 feet higher than North Lake, and a mile and 1,500 feet below the summit we were headed for.

Most people were meeting one another for the first time. It was very windy; the early group told us that the downdrafts that afternoon had struck the ponds so violently that water had been dashed into the air, until “everything smelled like trout.” Our campsite, however, was well tucked into boulders and trees and under the side of a granite bluff. The wind was still strong, but where we were, the gusts were baffled. Nevertheless, no one slept much in the noise of the wind. All night we could hear it rushing around the basin, roaring and whooshing in a chorus of rock edges and pine needles. Often we could hear a gust coming many seconds before it hit us. Our tents were struck from every direction, sometimes so hard there was a palpable slap to the face when a tent was squished. While Darryl DeVinney was still finishing his dinner, one gust tore his tent apart, and his air mattress flew off into the night, not to be found till the next morning. He had to take refuge under a nest of low trees, in a John Muir nook, wrapping himself in his tent remains and toughing it out.

Once you give up on the idea of sleeping during a night in the mountains, it can be very restful. If it is clear and not too windy, I dispense with a tent and sleep out. At 11,000 feet above sea level, the stars are simply incredible. I watch them, don’t try to sleep, and thus often sleep pretty well. Awake or asleep, in tent or out, a mountainous peace fills me.

Ten of us lay in this camp, three more were nearby, three were down at North Lake, and one was hiking through the night by headlamp. Another three would join us the following day in Mammoth Lakes, California. All these people were gathering to celebrate Thoreau, yes, but also our mountain range, for almost all of us had long relationships with the Sierra Nevada, and the truth is, it does not require much of an excuse to get a Sierra person to go up there again. Thoreau? Some kind of a thing? Of course!

We were also continuing a long tradition of meeting in the Sierra to celebrate its art. In the early Sierra Club summer trips, John Muir or Ansel Adams might tell a story by the fire or Cedric Wright play his violin. Here we were doing it again, awake in the dark and the wind. The feeling of that moment resists expression, has no name. It was the kind of party even Thoreau might have liked.

* * *

Friday morning dawned clear and gusty. We ate breakfast and took off up the basin’s north wall. This was the steepest part of the climb, but still a walk up, with the looseness of the decomposed granite our biggest problem. It was the two-steps-up-one-slide-down routine so common on sandy slopes of this kind. In general one seeks out the biggest rocks to step on. Even a rock the size of a dinner plate will generally hold one’s weight in the tilted sand. Walking poles are a big help for this kind of work, as they are for so much Sierra hiking. We slogged up for about an hour.

When we reached the edge of the peak’s little summit plateau, we sat for a while and watched Chris Woodcock catch up to us. Chris often takes night photos in the Sierra Nevada, very long exposures on color film, making for uncanny results. He had hiked all night by the light of his headlamp and taken photos of the peak at dawn from a vantage point across the basin. Despite his big backpack, he was moving fast.

After he joined us, we headed west and up to the peak. There was a little scrambling to be done near the top; the rocks got bigger, but they were more secure as well, so ultimately it was a bit easier than the sidewall of the basin. There was less and less rock and more and more air, so a surge of adrenaline came in scrambling up the last broken tilt of speckled granite.

Photo by Christopher Woodcock

It was a big view. California’s Central Valley was visible to the west, filled with thick clouds like smashed thunderheads. To the north across Piute Canyon, we had a good view of Mount Emerson’s gray serrated south face, and the red Piute Crags that extend eastward from it. Looking east over North Lake to the Owens Valley, we could see across to the White Mountain range. To the south stood Mount Darwin, and to the southeast, the Palisades. Directly below us to the south was our camp; below us in the other direction we looked down on Humphreys Basin, a giant expanse of rock, sloped like the roof of a church.

Photo by Darryl DeVinney

There were 11 of us on top. We left our new register box, an antique metal card-filing box found in a thrift store, on a flat spot near the highest point. The notebook inside had been signed first by Gary and other friends the day before (“I send these people up from North Lake”); those of us who had accomplished the summit signed it there. When the box was secure under a big rock, Chris arranged a group photo. Then we sat for a while longer, looking around. As Gary writes in Danger on Peaks, “Snowpeaks are always far higher than the highest airplanes ever get.” When you’re up on a mountaintop, you see what he means.

The descent was easy. You reverse what you tried for going up and aim for the sandiest places in order to glissade down. There’s time to look around and think, and for a while as we dropped, I considered what Thoreau himself would have thought of our project.

I doubt he would have approved. For him California meant the Gold Rush, which he considered a stampede of desperate and confused people. More generally, he often said that traveling was a mistake, an attempt to escape a self that can never be escaped. “I am much traveled in Concord,” he replied waspishly to someone who encouraged him to see the world. So, a plaque at Walden Pond, maybe. A peak on the far side of the continent: no way.

But as I glissaded down the slope, it seemed to me also that a part of him might be pleased by our gesture, simply as an indication that his books had gotten read. Recall that when he died, most of the first edition of Walden was in boxes in his basement. It looked like his books were going disappear like pebbles thrown in a pond. That they became famous, and are often loved, might surprise him, but would surely please him, too. Why not?

Also, during his travels, limited though they were, his few mountain encounters excited him. His vivid description of an ascent of Maine’s Mount Ktaadn (a spelling Thoreau preferred to “Katahdin”) is one of the most famous passages in American literature, a wild attempt to express the inexpressible.

Images courtesy of Library of Congress

Also, there is an unusual entry in Thoreau’s journal, recording a dream he had about a mountain. It’s the entry for Oct. 29, 1857, and begins, “There are some things of which I cannot at once tell whether I have dreamed them or if they are real.” He continues:

This morning, for instance, for the twentieth time at least, I thought of that mountain in the easterly part of our town (where no high hill actually is) which once or twice I had ascended, and often allowed my thoughts alone to climb. I now contemplate it in my mind as a familiar thought which I have surely had for many years from time to time, but whether anything could have reminded me of it in the middle of yesterday, whether I ever before remembered it in broad daylight, I doubt.

He describes his climb:

I steadily ascended along a rocky ridge half clad with stinted trees, where wild beasts haunted, till I lost myself quite in the upper air and clouds, seeming to pass an imaginary line which separates a hill, mere earth heaped up, from a mountain, into a superterranean grandeur and sublimity. What distinguishes that summit above the earthy line, is that it is unhandselled, awful, grand. It can never become familiar; you are lost the moment you set foot there. You know no path, but wander, thrilled, over the bare and pathless rock, as if it were solidified air and cloud. … It is as if you trod with awe the face of a god turned up, unwittingly but helplessly, yielding to the laws of gravity.

Following this eerie passage he added a poem rehashing the dream and wondering what it might mean. As good a prose writer as Thoreau is, he is almost exactly that bad a poet, and for the most part he gave up writing poetry in his youth. But here he tries again, and says of his dream mountain: “It is a promised land which I have not yet earned.”

This is a little sad to read. If the dream mountain was something inside him, as obviously it was, then maybe it could be taken to be a symbol of the journal itself, a veritable mountain of pages. This project, the core of his life, always interesting, frequently incandescent, is one of the greatest books ever written. Surely he had earned the right to ascend it, having built it.

Possibly he sensed something like this, for near the end of the poem he writes:

It is a spiral path within the pilgrim’s soul

Leads to this mountain’s brow

His journal wasn’t published until 44 years after his death. Near the end of his life, knowing he was dying, he built a stout cedar box to hold the journals, as if building his own coffin, and he gave the box to his sister for safekeeping. He could never know what he had accomplished. But we know. So we named a peak for him.

* * *

Back in camp we packed up, ate lunch, took off, and immediately got lost in the rock maze. Despite this we blundered down to the trail without much loss of time and dropped quickly to North Lake, where we rejoined the others and drove to Valentine Camp, part of the University of California system’s field research station near Mammoth Lakes.

There we finally gathered as one group. We ate dinner in the biggest cabin and got to know one another; no one knew everyone else there, as friends had invited friends who had invited friends. There were 20 of us now, and it was a fun evening, a mixer. On hand were Michael Blumlein, Brigid Breen, Isabella Breen, Dick Bryan, Tom Buoye, Darryl DeVinney, Laurie Glover, Hilary Gordon, Tom Killion, John Markoff, Paul Park, Armando Quintero, David Robertson, Jeanette Robertson, Stan Robinson, Charlie Schneider, Carter Scholz, Gary Snyder, Leslie Terzian, and Chris Woodcock.

The next night we celebrated Thoreau with some show and tell. Thoreau hated schools and parties, so we didn’t make a big deal of it, but despite that, or maybe because of it, after a while it began to feel a little bit like it had on the mountaintop. It was Paul who started this, another New England writer and outdoorsman, reading the famous Ktaadn passage with just the mix of precision and barely caged emotion that Thoreau himself so often displays. After that we were slightly electrified, and the other talks kept that going. Michael spoke of Thoreau’s youthful self-righteousness, so similar to ours, and then of his respect for other forms of life, illustrating this by reading the part of Walden that describes the battle of the red and black ants. Dick then made an affectionate and funny analysis of Henry’s personal economics during the years at Walden Pond (his laundered costs included his mom doing his laundry). David spoke of him as a “semi-religious” writer and talked about how Gary’s poetry also had that quality. Laurie sang a ballad she had written that day about our trip, and we joined in on the chorus, seriously mangling the tune. Mando told us of his meeting with some of John Muir’s descendants and the feeling of reading some of Muir’s private papers, including a childhood primer of Muir’s that had scrawled on its last page, Tomorrow we’re gone to America. Tom Killion showed us images of his Sierra woodblock prints, so startling in their clean color and line, their beauty and rightness. Gary read some new poems, including a wonderful one about Ötzi the ice man and what he might have been doing as he attempted to cross that pass in the Alps 5,000 years ago. Chris Woodcock showed us a selection of his night photos, in which the abstract forms of the Sierra resemble immense ruins. I finished by reading the journal entry about the dream mountain, and at that point, hearing Thoreau think about the meaning of mountains was like having him talk to us, responding to what we had shown or said or sung, joining in on the session.

After that we went back to partying. We had made our contribution to the long tradition of mountain campfire storytelling. As Gary’s poem reminded us, the tradition at this point is thousands of years old.

Photo by Kim Stanley Robinson

Hopefully the name will stick to Peak 12,691. It will if people like it. And maybe they will. Thoreau was a small-town guy, a bachelor who took odd jobs, lived mostly with his parents, and spent much of his time wandering in the woods. But he paid attention to his neighbors and his neighborhood, and wrote down what he saw in prose so precise and expressive that reading it is like proof of concept: ah, yes, language works. We can speak to each other, even across the centuries, and get something across the gap.

Surely this jump from mind to mind has to do with naming things. All our nouns are names, and often we name things that are huge or various or intangible. We try to name everything.

Of course that includes our surroundings. In the Alps every big boulder has a name, and it’s the same anywhere people have lived for a long time. It was the same in the New World, too, but we forgot the names the first peoples used, or never knew them.

Now we’ve decided to stop putting names on wilderness places, even though wilderness itself is a name we’ve made up. For the most part I like the idea of wilderness and the decision to keep it largely nameless. Many times we’ve crossed a Sierra ridge in the late afternoon and looked down on a remote trailless basin, sunlight banging off nameless lakes, surrounded by nameless peaks, and it does feel wild, as if we were exploring some new empty planet—or as if we were the first people to walk into the New World, 20,000 or 30,000 years ago. It’s a thrilling feeling.

But in this case I think the honor of the name is worth the loss of the unnamed. Emerson and Thoreau were friends, and together they changed us. Now their two peaks form a gate like the Pillars of Hercules, marking a way into a certain kind of American reality, as well as a bit of Sierra backcountry. In wildness is the preservation of the world.

Thoreau’s journal, which so often names things, has been criticized for becoming too particular, too concerned with birds and bugs and plants. He changed, some say, from a great transcendentalist to just another citizen scientist. It was not a change, but a sharpening of focus; writing the world became his devotional practice. Now his name stands for that kind of worship.

The passage about climbing Ktaadn ends like this:

Here not even the surface had been scarred by man, but it was a specimen of what God saw fit to make this world. What is it to be admitted to a museum, to see a myriad of particular things, compared with being shown some star’s surface, some hard matter in its home! I stand in awe of my body, this matter to which I am bound has become so strange to me. I fear not spirits, ghosts, of which I am one,—that my body might,—but I fear bodies, I tremble to meet them. What is this Titan that has possession of me? Talk of mysteries!—Think of our life in nature,—daily to be shown matter, to come in contact with it,—rocks, trees, wind on our cheeks! the solid earth! the actual world! the common sense! Contact! Contact! Who are we? where are we?