Good Times Bad Times

Modern rock didn’t start with Dylan or the Beatles. It started with Zeppelin.

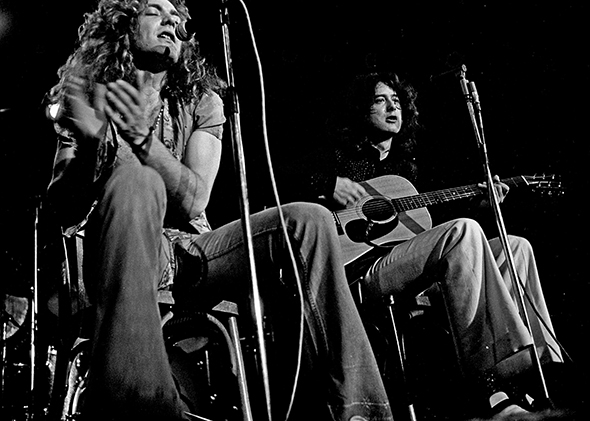

Photo by Heinrich Klaffs/Wikimedia Commons

It is early 1969, and you are young. You hold in your hands an LP by a band with a strange name. The cover art is a black-and-white photo of the Hindenburg exploding, cropped and retouched to resemble some phallic, Nazi apocalypse. You remove the record from the sleeve and place it on your turntable. The sound of a guitar explodes into your ears, two quick bursts of a Fender Telecaster, each lashed to a violent drum hit: BOM-BOMP. The next two minutes and forty-some seconds roll by like an avalanche, intricate webs of guitar and bass, thundering percussion, a 20-year-old vocalist belting lines like “I know what it means to be alone” with a flamboyance that makes it impossible to believe him. When it all ends you grab the needle and move it back to the record’s edge, to confirm all this is real, and it all begins again. BOM-BOMP.

That twin blast of an E chord (of course it’s E) is the opening sound of “Good Times Bad Times,” the first track on Led Zeppelin, which would soon be known as Led Zeppelin I once Led Zeppelin decided to name their next two albums after themselves as well. In 1969 it was as powerful a shot across the bow of pop music as the “one two three fuh!” that had kicked off “I Saw Her Standing There,” the glowing Wurlitzer that had opened “I Never Loved a Man (The Way I Love You),” the blinking, blaring tritone that had heralded “Purple Haze.” It was the sound of a new world being born, and the louder sound of an old world being destroyed.

Led Zeppelin, Led Zeppelin II, and Led Zeppelin III have recently been given deluxe reissues by Atlantic Records. Each package contains a remastered version of the original album, along with a generous helping of bonus tracks. The first boasts a live set from a concert in Paris in 1969 (which has been floating around the Internet for years) while the second two include collections of rough mixes from the sessions from Led Zeppelin II and Led Zeppelin III, respectively.

The remastering is pretty superfluous: These are, and always have been, three of the most perfect sounding rock albums ever made. The rough mixes of II and III, though, are a revelation, casting light on Jimmy Page’s immense talents as a producer and giving us the opportunity to rediscover this band as they were, four absurdly gifted young people making music together, as opposed to the rock deities they’d forever after be imagined as. You can hear Page’s pick scraping string on a demo-ish “Whole Lotta Love,” Robert Plant feeling his way through an early pass at “Ramble On,” Bonzo counting the band back in on a skeletal version of “Moby Dick,” the careful interplay of Page’s acoustic and John Paul Jones’ mandolin on a rough cut of “Gallows Pole.” Listening to the ragged life behind these recordings reminds us, on the one hand, that four guys made these records. It also reminds us, on the other, that four guys made these records. Sometimes being made human only heightens your immortality.

Photo by David Redfern/Redferns/Getty Images

Led Zeppelin’s legacy is fittingly long and fittingly loud. Depending on your preference in white male hagiography, “modern” rock music is often said to have started with Dylan’s “Like a Rolling Stone,” or Sgt. Pepper, but these myths are wishful, and overly fanciful: Modern rock music started with Led Zeppelin. Their influence, for better and worse, over all that’s come since is singular. Punk in the 1970s was a rejection of their pompous pretentiousness, metal in the 1980s an affirmation of their excesses, grunge in the 1990s a reclamation of punk that often sounded a lot like Led Zeppelin. We have Led Zeppelin to blame for Creed; we have Led Zeppelin to thank for the White Stripes. They were a band loved by millions, but if you were smart, or just cool, you probably hated them. Led Zeppelin lifted popular music to new heights of opulence and ambition and in doing so made people fear for its future. They were a microcosm of age-old anxieties about music and commerce and youth and race and sex: if the music of the ’60s—Motown, the Beatles, Stax and Muscle Shoals, Woodstock—brought unprecedented consensus, Led Zeppelin brought something like the opposite. Forty-five years later, we live in their aftershocks.

* * *

Led Zeppelin was an idea before they were a band, and that idea was always huge. Jimmy Page was a former skiffle prodigy who by the mid-1960s had made himself into one of the top session guitarists in England, playing on hits ranging from Donovan’s “Sunshine Superman” to Petula Clark’s “Downtown.” In 1966 he joined the Yardbirds (enjoying a cameo in Antonioni’s Blow-Up), but the band was already on its way to breaking up. Page conspired to form a “supergroup” with ex-Yardbirds guitarist Jeff Beck and the Who’s John Entwistle and Keith Moon. Someone (Entwistle or Moon) joked that the idea would go over like a lead balloon—a “lead zeppelin.”

The lineup didn’t stick but the joke did. When Page recruited a singer from Birmingham named Robert Plant, a ferocious drummer named John Bonham, and a bassist and musical polymath called John Paul Jones to join his project, they dropped the A from the first word out of fears that Americans would mispronounce it “leed zeppelin.” Led Zeppelin signed with Atlantic Records, the legendary R&B label that had made superstars out of Ray Charles, Otis Redding, and Aretha Franklin, for an unprecedented six-figure advance. Led Zeppelin was the first significant band to emerge from a post–British Invasion world and effectively reversed its trajectory. They conquered America before even bothering with their home country: Led Zeppelin was released two months earlier in the States than it was in England, and on an American label to boot.

For a band so fundamentally associated with the 1970s, it’s startling to remember that Led Zeppelin came out seven months before Woodstock, eight months before Abbey Road, 11 months before Altamont. Much like Never Mind the Bollocks, Here’s the Sex Pistols or Straight Outta Compton, Led Zeppelin was an enormously important album that wasn’t an entirely great one. It had two exquisite tracks (“Good Times Bad Times” and the nastily brutish “Communication Breakdown”), but much of the rest was uneven and bloated, alternately half-baked and overbaked. The album’s centerpiece was the six-and-a-half-minute “Dazed and Confused,” a morass of shrieking chromaticisms and asinine misogyny. It would quickly become one of the band’s most iconic works, stretched to 20 or 30 minutes in concert, replete with gongs, vocal histrionics, tricked-out guitars played with violin bows.

“Dazed and Confused” is a lousy song, the musical equivalent of plastering a horrific tragedy on your album cover and then asking your art department to make it look more like an erection. For the band’s detractors, “Dazed and Confused” was an easy metonym for everything wrong with Led Zeppelin: loud, overlong and oversexed, plagiarized (“Dazed and Confused” had been originally recorded by American folksinger Jake Holmes in 1967; Led Zeppelin changed just enough to avoid crediting him).

And from the beginning, those detractors were vocal. One of the well-worn saws of Led Zeppelin lore is that they were universally loathed by the critical establishment. Like so much about the band, this is a partial truth that’s been exaggerated in the retelling. Plenty of critics liked Led Zeppelin and plenty more politely tolerated them (the British press were particularly enthusiastic—New Musical Express breathlessly declared them “a blitzkrieg of musically-perfected hard rock that combines heavy dramatics with lashings of sex into a formula that can’t fail to move the senses and limbs”). What is true is that a certain very influential contingent of writers hated them. Specifically, Rolling Stone magazine hated Led Zeppelin and hated them during a period in which the publication was consolidating its reputation as the world’s most influential organ of rock journalism. Critic John Mendelsohn, reviewing Led Zeppelin for RS in 1969, lamented the album’s “weak, unimaginative songs” and “prissy Robert Plant’s howled vocals,” and sniffed that Page’s foursome was a long way from filling the shoes of the recently disbanded Cream.

Like all narcissists who love to tell you how little they care what other people think of them, Led Zeppelin cared deeply about what other people thought of them. One of the most interesting aspects of the band’s early career is how carefully they seemed to be reading their own negative reviews: If these were rock gods in the flesh, the flesh was thin-skinned. English fans might open a copy of Melody Maker and find a fawning interview with Jimmy Page in which the guitarist would nonetheless take a detour to complain, in striking detail, about a negative review of a Led Zeppelin concert published in the paper a few weeks back.

Led Zeppelin II arrived in October 1969, a mere nine months after Led Zeppelin, an incredible feat given the band’s grueling touring schedule. Led Zeppelin II opened with “Whole Lotta Love,” which became the band’s first proper “hit,” peaking at No. 4 in the States in early 1970. Today “Whole Lotta Love” is so famous that it’s easy to forget that it’s probably one of the stranger singles to scale the upper heights of the Billboard charts. For starters, it’s not much of a song: There are no chord changes to speak of, and the “bridge” is an extended interlude that sounds like someone faking (?) an orgasm in a haunted house. The rest of the track is just a guitar riff supplemented by Plant intoning lame pickup lines. And the pickup lines aren’t even his: The lyrics to “Whole Lotta Love,” originally credited to Page and Plant, are blatantly lifted from Willie Dixon’s composition “You Need Love,” a theft redressed only after Dixon took the band to court.

(It’s worth pausing to marvel at the unbelievable stupidity of this. For starters, “You Need Love” was first recorded by Muddy Waters in 1962, as the follow-up to his hit “You Shook Me”—which Led Zeppelin had covered on their previous album. Secondly, Dixon wrote some great lyrics in his day, but these certainly aren’t them, unless you think the opportunity to rhyme “coolin’,” “foolin’,” and “schoolin’ ” is worth being hauled to court over. The “Whole Lotta Love” plagiarism was a failure of ethics, execution, and just plain good taste.)

All that said, “Whole Lotta Love” is Led Zeppelin at their most essential. It’s big, loud, riff-driven, not terribly bright, and probably twice as long as it ought to be. It’s also an incredible piece of music that creates a five-minute cauldron of volume, rhythm, and sex about as effectively as anything ever has (and so many things have tried). It instantly became the iconic track of Led Zeppelin II, which was predictable but also a bit of a shame, as it eclipsed the enormous strides the band made elsewhere on the album. “What Is and What Should Never Be,” was an actual song, with structure and dynamics and intelligence and everything else Zeppelin wasn’t supposed to be doing, and “Ramble On,” which boasted an exquisite guitar arrangement by Page and a jaw-dropping bass performance from Jones, showcased the band’s increasingly peerless musical abilities.

Like the band’s first album, Led Zeppelin II was produced by Page, and it marked his full emergence as one of the great studio architects in popular music. Every sound captured on the album is extraordinary: Instruments swoop between stereo channels, the bass and drums blend perfectly against each other, Plant sounds like he’s in the room with you even when he’s off singing about Middle Earth. And the guitars—good lord, the guitars. Page is frequently compared to British blues counterparts like Eric Clapton and Jeff Beck, but he’s really the descendent of another mainstay of the 1960s British scene: Jimi Hendrix. Only Hendrix had such a similarly effortless grasp of the guitar as a palette of sonic possibility, a conduit to new auditory worlds. The riffs on “Whole Lotta Love” and “Heartbreaker” and “Moby Dick” sound so familiar to us that we forget that nothing had ever really sounded like them before. Page was overrated as a soloist, but guitar solos are almost always overrated; his best work was everywhere else.

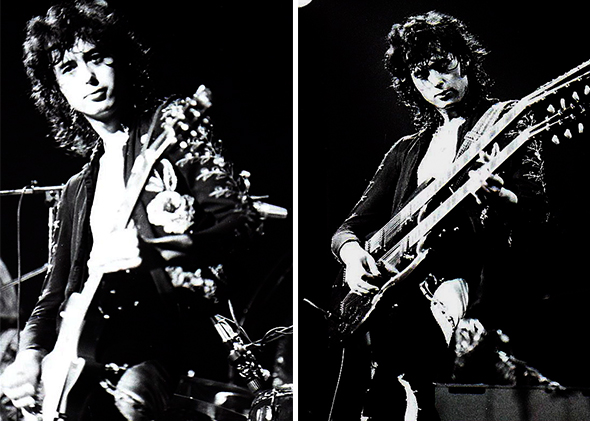

Composite by Slate. Photos by Dina Regine/Flickr.

Led Zeppelin II was a commercial smash—it knocked Abbey Road off the top of the charts in the States—but it failed to change the hearts and minds of the band’s critics. Rolling Stone’s notorious trashing of the album, again penned by Mendelsohn, is very funny, very mean, and very wrong, and even its tongue-in-cheek praise of Page as “the absolute number-one heaviest white blues guitarist between 5’4’” and 5’8” in the world” is downright slanderous—Page is 5’11”. But in the review’s contempt we see a new narrative emerging, that Led Zeppelin were simply the next and worst generation of blues plunderers, the limit case of white opportunism. At least Jagger and Janis had been reverent. Couple this with the plagiarism escapades, and accusations of wholesale cultural larceny abounded.

Again, there were some elements of truth to this: Led Zeppelin had a relationship to the blues (and black music generally) that could veer between brilliantly creative and stupidly abusive, sometimes within seconds. “Bring It On Home,” the last track of Zeppelin II and one of the best cuts on the album, is nearly destroyed before it gets started by an interminable intro that’s little more than a smirking, down-home grotesque.

But Led Zeppelin weren’t a minstrel show—they were something so much weirder. To suggest that all they did was steal from the blues is an insult to the band, but also to the blues. Zeppelin’s appropriations could be bereft of ethics, but they were more often just bereft of logic: Here was a band that wedded Robert Johnson-isms to plots borrowed from Tolkien novels with no sense of incongruity, or embarrassment.

The problem with Led Zeppelin was never really what they’d stolen from the blues, but what they hadn’t: economy, wit, taste. And it’s worth noting that these accusations predominantly circulated among white male rock writers: The line between Led Zeppelin violating the blues and Led Zeppelin violating certain people’s beliefs about the blues was rarely a bright one.

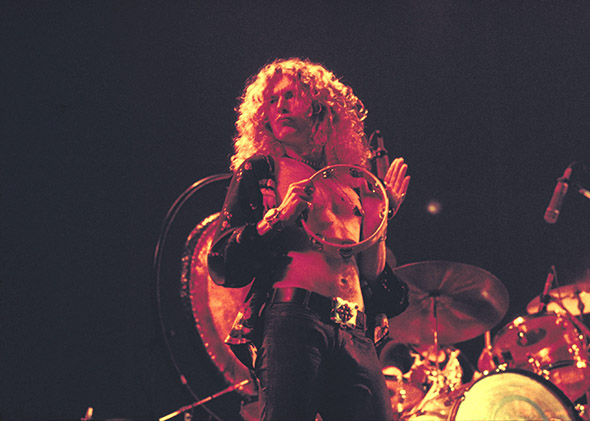

Photo by Dina Regine/Flickr

Led Zeppelin had started as an idea, and was now despised as one. But why did people really hate Led Zeppelin? The rock ’n’ roll of the counterculture had been supposed to change the world and hadn’t. Maybe you blamed Dylan’s motorcycle, maybe you blamed Yoko or Paul or Nixon or the Hells Angels. Now you could blame Led Zeppelin, as “All You Need Is Love” had given way to “I’m gonna give you every inch of my love.” They represented someone’s cynical fantasy of the masses, a coalition of louts and groupies and wasted youths who, come to think of it, probably weren’t even reading rock criticism in the first place. The revolution had failed, and Zeppelin was playing its wake, and cashing in—the amount of money they made was an obsessive topic in coverage of the band (“Led Zeppelin and How They Made 37,000 Dollars in One Night,” blared a 1969 headline). Rock ’n’ roll had once been art for art’s sake, or the world’s sake: now it was just art for money’s sake, and Page & co. didn’t even have the decency to pretend otherwise.

And then Led Zeppelin blew everything up, again. Led Zeppelin III, released in October 1970, opened with “Immigrant Song,” a screeching, pummeling anthem about Viking invaders. The only way “Immigrant Song” could have sounded more like a parody of Led Zeppelin is if it were seven minutes long as opposed to a mere (blessed) two and a half. If you hated Led Zeppelin, “Immigrant Song” confirmed everything you thought you knew, and you may have stopped listening there.

But anyone who didn’t stop there would have been surprised, and seriously confused. Led Zeppelin III was an album of real songs, enormous eclecticism, and startling beauty, and the album’s second side contained the finest collection of unplugged rock music this side of Beggars Banquet. “Gallows Pole” was a reworking of an ancient British ballad that boasted acoustic guitars, mandolin, and banjo, and built to a weird, modal rave-up of charging drums and a lush guitar solo. “That’s the Way” was gorgeous, worthy of inclusion on the Joni Mitchell and Fairport Convention albums the band was listening to with obsessive frequency.

And then there’s “Tangerine,” a song Page had written years earlier that’s probably the prettiest recording Led Zeppelin ever made. The 12-string guitar sparkles, Bonham plays with uncharacteristic sensitivity, and Plant sings Page’s lyrics with a vibrato that’s almost Presleyan (a stylistic departure so striking that one critic speculated it was a guest vocalist). “Tangerine” is one of only a handful of Zeppelin tracks that’s totally perfect, not a second too long, not a note unnecessary or out of place (“Hey Hey What Can I Do,” the phenomenal B-side to “Immigrant Song,” is another, although good luck finding it here—in too-clever-by-half fashion, Led Zeppelin left the best song they’d ever written off an album).

Led Zeppelin III was a shocking musical curveball and remains the strangest album in the band’s catalogue. It debuted at No. 1 because it was a Led Zeppelin album, and then sales dropped, because—was it a Led Zeppelin album? And it still didn’t garner the acclaim the band sought, met with confusion or dismissive contempt by writers who barely seemed to have listened to it. “It would be hard to imagine a popular musical organization that is any more consistently ugly than Led Zeppelin,” the New York Times declared, in the opening sentence of its review. The song remained the same, even when it didn’t at all.

* * *

Photo by Chris Walter/WireImage/Getty Images

When victory did finally come for Led Zeppelin it came like everything else had—massively. In November 1971 Led Zeppelin released their fourth album, which bore no title but would soon come to be known as Led Zeppelin IV. It contained the band’s self-styled masterpiece, “Stairway to Heaven,” along with their actual masterpiece, “When the Levee Breaks.” Today Led Zeppelin IV is widely regarded as one of the finest albums ever made (Rolling Stone even liked it!) and has sold nearly 40 million copies. It cemented Led Zeppelin as the biggest band of the post-Beatles era, even if returns afterward were diminishing. 1973’s Houses of the Holy was a very good album that was a step down from the work that preceded it. 1975’s Physical Graffiti was a double album that would have been great had it been a single album. 1976’s Presence just wasn’t very good, and 1979’s In Through the Out Door wasn’t much better.

When John Bonham died in 1980 the band called it quits, but the Led Zeppelin idea endured. When This Is Spinal Tap premiered in 1984, the affectionate resemblance loomed larger than Stonehenge. In 1985 the notorious tell-all biography Hammer of the Gods was published and became as seminal a ninth-grade text as Of Mice and Men, despite the band insisting its tales of occult hijinks and hotel debauchery were grossly exaggerated (although the “Shark episode” Wikipedia entry swims on in infamy). In 1986 a trio of youngsters from New York released an album whose cover bore no small likeness to Led Zeppelin and opened with the drums from “When the Levee Breaks.” The Beastie Boys’ Licensed to Ill was Led Zeppelin for the kids of the people who’d bought Led Zeppelin, and those parents were appropriately appalled.

By the time Led Zeppelin were inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1995 they’d faded into archetype, open-shirted lead singers and Les Pauls slung around the knees having long since lost their ability to be thrilling or crass. And the three surviving members of the band have aged remarkably gracefully, with Page taking his rightful place as a public intellectual of the electric guitar, Plant reinventing himself as a Grammy-winning interpreter of high-end Americana, and John Paul Jones enjoying the family life (he’s been with his wife since 1965) while occasionally joining other Zeppelin-ish supergroups. In fact, one of the most impressive achievements of the ex-members of Led Zeppelin is how deftly they’ve each disentangled themselves from Led Zeppelin. But they can’t really, no more than any of us can. That murderous burst of guitar that opened “Good Times Bad Times” did everything it was supposed to, and everything it wasn’t: It changed the world.