“Bad Romance,” Great Tritone

Explaining the genius of Lady Gaga—using music theory.

Photo by Tim Mosenfelder/Getty Images

Our mission: to dissect chart-topping pop singles and weigh their trembling flesh on the scales of Western music theory. Today I am typing about the unique genius of Lady Gaga’s “Bad Romance.”

From her early singles onward—“Just Dance” (U.S. No. 1), “Poker Face” (U.S. No. 1), “LoveGame” (U.S. No. 5), “Paparazzi” (U.S. No. 6), “Bad Romance” (U.S. No. 2), “Alejandro” (U.S. No. 5), and “Judas” (U.S. No. 10)—Gaga and her primary songwriting partner, RedOne, set rigorous guidelines as to what Gaga singles would or would not do:

1. Gaga is meant to convey a sexy, spooky energy. Result: Gaga would not release any major-key singles. Minor keys only. None of these seven singles is in a major key.

2. Gaga’s presence on the charts is monolithic, immovable. Result: Gaga would begin every verse (and most choruses) on the establishing i chord, that is, the root chord of the minor-key the song is in, suggesting permanence, an inevitability.

3. Gaga’s gaze upon the pop landscape is unflinching, unblinking. Result: Gaga would never do a single that modulated to another key. (Exception: “Paparazzi”)

4. Gaga is human, obeys her base impulses, with no uplifting effervescence or fluttery naiveté. So, despite the best advice of certain music writers, Gaga would never allow any of her dance-floor fillers to feature syncopated rhythms. Only repetitious juggernaut eighth-note patterns, please. (Exception: “LoveGame.”)

5. Gaga isn’t above high-fiving a stereotype once in a while. So, many of these singles feature spoken-word breakdowns with overtones of wide-eyed infantilism (“disco stick,” “bluffin’ with my muffin”) or French-maid fetishism (“Alejandro’s” intro, “j’veux ton amour et je veux ton revanche” [sic]).

6. Gaga has her sights set on the world stage, not just English-speaking countries. Result: All of these singles repeat the song title enough times so as to penetrate the language barrier. On her first five singles, she sings the song’s title 18, 30, 34, nine, and 36 times, respectively—I gave up counting by the time I got to “Alejandro.”

“But all of these songs sound the same,” you protest. You are correct. From song to song, Gaga likes simple, laserlike single-pitch melodies—compare “I want to hold them like they do in Texas please” with “I want your ugly, I want your disease” with “When he comes to me I am ready.”

She loves the interval of a perfect fifth—compare “Bad Romance’s” “Gaga ooh la” fanfare with “Paparazzi’s” “We are the crowd / We’re c-coming out” with “Judas’ ” “Judas Judaaaaas.”

Regarding her chord choices, well, I penciled them down, and I’ll give you the tl;dr version: She and RedOne keep it simple.

Some poppets may take this consistency of tone to be indicative of a “lack of creativity” on Gaga’s end. Me, I see it as strong branding. Yes, these seven singles are mechanically indistinguishable, but I hear L-A-D-Y on the left, G-A-G-A on the right, knuckles in your face, your inner ear is branded. Gaga is a fighter, not a lover.

I like this monomania, too, as it definitively establishes Gaga’s own voice as a songwriter. She works with co-writers, as do most pop singer-songwriters, but her own writing voice is indelible. I respect performing artists and songwriters equally, but I extend extra good will to those artists who take on both roles. This is not because of any desire for “authenticity of authorship,” but because I, as an audience member, like superheroes.

And you cannot deny the efficacy of her narrow compositional vocabulary. I use the word “genius” without reservation. She is one of the most successful participants in the culture industry, resonating worldwide with people in all walks of life. If you wish to debate the worth of this industry, or whether or not “genius” can exist within it, we can do so at another time. Here is a video of Haitian kids singing and dancing to “Poker Face”:

All of the scene-setting of The Fame was to prime the world for Lady Gaga’s best and (as time will surely show us) most enduring pop single: “Bad Romance.” “Bad Romance” is Gaga’s magnum opus, a summation of her musical vocabulary, that expands upon the foundation of her first singles, and towers over her more recent ones.

I have to mention three non-music-theory-related points about “Bad Romance” in passing. First: The vocals on the chorus are cunningly mixed far louder than the verses, just to make sure we hear how great a chorus it is. Second: The signature spoken-word breakdown is no longer reminiscent of crass Peaches, but sexy Janet. Third: “Bad Romance” is, to the best of my knowledge, the only Gaga single to have its final chorus overdubbed with pop-diva-style vocal improvs.

The distinguishing compositional features of “Bad Romance” are mutations, odd alterations to her business as usual. Chiefly, the chorus (and song) begin on a VI chord instead of her favorite i chord. Structurally, the song is an epic, packing many parts into itself, reordering the structure and modifying the breakdown, a mutation on a mutation.

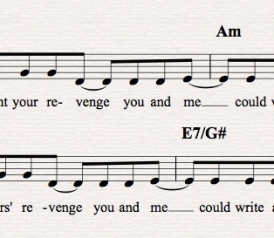

The chorus itself shifts and changes. It appears right off the top as the wordless “oh-oh-oh-oh-ohhh”—a melisma, a normal enough occurrence in pop, but Gaga hasn’t done melisma before or since. This melisma is just foreshadowing for the chorus proper, where it is replaced with the hook “I want your love and I want your revenge / you and me could write a bad romance.”

About that hook: Gaga has till now never used a “raised seventh,” which is unusual for someone who writes exclusively in minor keys. Now she does. In this chorus there is a changing accidental—the seventh note of the a-minor scale appears both as a G-natural and as a G-sharp.

Now, this raised seventh does something that would make Tchaikovsky proud. The melody appears twice per chorus, but over two distinctly different chord progressions (VI-VII-i-III the first time, VI-VII-V-i the second). The first time, “bad” appears as G-natural, leaping down a fourth to “romance.” The second time, “bad” appears as a G-sharp, leaping down a tritone.

That G-sharp wants to go upward. It wants to rise to the A, resolving the cadence as a music school freshman would have done. But Gaga goes down, leaving that “bad” leading note hanging. Why? Because she herself is bad. Further accentuating the badness of that “bad”: That interval, the tritone, is historically linked to sexual desire and the devil. Whether or not Lady Gaga is familiar with the specifics of Tchaikovsky’s Sixth Symphony is irrelevant; she has scored a textbook-worthy usage of Western music theory’s favorite signifier for EVILDOING.

Aside from these important deviations, all the key features of Gagaism are here, those rules listed above. And this is why “Bad Romance” will endure forever, because all six of these other singles will only be heard as inferior sketches and imitations of the masterwork—in “Judas’ ” case, a poor photocopy, melismatic “ohhh” included. “Bad Romance” stands on the shoulders of these other, identically dressed, homelier singles, the star cheerleader, No. 1.

Before I get off this boat, I have to patch a couple of holes. I’ve been limiting my focus to the RedOne collaborations, plus “Paparazzi”.* A few words about the Gaga’s other singles:

“Born This Way” (U.S. No. 1) is Gaga’s biggest smash, her first in a major key. Now, I personally believe that originality in songwriting can extend outside the boundaries of melodic and harmonic creativity, but as far as Western music theory is concerned, that song was written by Madonna.

“Telephone” (featuring Beyoncé) (U.S. No. 3) and “Do What U Want” (featuring R. Kelly) (U.S. No. 13) are stylistically divergent duets, so they don’t count.

“Applause” (U.S. No. 4), the first single from Artpop, conforms to most of the “traditional” tenets of Gaga’s writing—straight eighths, minor-key, repetitious simplicity—and it was a respectable success. In contrast, Born This Way’s strange and nonconforming misstep “Yoü and I” (U.S. No. 6 but lower elsewhere) was a minor hit by Gaga standards.

My most glaring omission, however, is “The Edge Of Glory” (U.S. No. 3), a big, exciting, major-key hit, which, honest to God, I’d heard and enjoyed a hundred times before typing this article but would’ve never guessed was Gaga. I am on a bus, I hum the chorus to the people sitting on both sides of me, and they know the song, but they also guess wrong. They thought it was Kelly Clarkson. I cite this as further proof of the efficacy of Gaga’s branding. Thanks for reading.

*RedOne is only featured on one track on Artpop, “Gypsy”; the scaling-down of his involvement was what inspired this piece.