Slate is an Amazon affiliate and may receive a commission from purchases you make through our links.

Bless Me Father

Patricia Lockwood’s writerly touch in her family memoir is almost too light.

Sam Octigan

If certain muses love certain writers, Patricia Lockwood seems to have a special relationship with the muse of fun. For her, fun is more than part of a life well-lived. It has aesthetic value and can open the door to other literary goods: freedom, freshness, generosity of spirit. Even “Rape Joke,” the furious and beautiful poem for which she is best known, deploys a deceptively silly and irreverent style. Lockwood’s commitment to fun burns bright in Priestdaddy, her new memoir about growing up in a devout Catholic family.

When she moves back to her parents’ home in Kansas City, Missouri—she and her husband Jason need to save money for his emergency cataract surgery—she describes amusing herself with a game called “I Guess the Plots of My Father’s Favorite Movies Based on the Sounds Coming Through the Walls.” Elsewhere, she gets drunk with a seminarian (and transcribes her antic riffs on St. Augustine: “Oh God, don’t make me good, not ever,” “Oh God, make me a VERY bad boy, who needs a spanking”). Her very language is fun, a tonal kaleidoscope of faux-gravity and giddiness and sarcasm. Lockwood’s lyric elevation of fun is wonderful and seemingly related to her affection for her family. But one lesson of Priestdaddy might be that such lightness is not lightly achieved.

Lockwood takes obvious delight in the larger-than-life characters who raised her: Greg Lockwood, a priest granted special dispensation to keep his wife and children around after he converted to Catholicism, and Karen Lockwood, a wacky, punny conspiracy theorist who shares her daughter’s verbal gifts.

At first blush, it is Greg who sucks up most of the book’s oxygen. He is an obstreperous diva who parades through the house in see-through boxer shorts, abuses a rainbow of pricey guitars with his “ass rock” solos, hoards cream liquors, and intimidates Jason with his gun collection. He actually evokes another colorful character in recent pop cultural memory: John McLemore, the vivid eccentric at the center of S-Town and a man whose arrant strangeness seemed to forecast a story consumed by the project of cataloging his many quirks. Both John and Greg are driven by appetite but profoundly concerned with moral purity. (The possible contradictions here seem to trouble McLemore more than they do Lockwood.) They opine on the world in extravagantly, mischievously baroque language. S-Town and Priestdaddy point to the challenges of building rich, textured nonfiction around figures so florid that it’s tempting for the narrator to give up on empathetic storytelling and merely gawk.

How to solve this problem? S-Town deepened our understanding of McLemore by adding layer after layer of emotional complexity, inviting us to discover the person beneath the performance. Lockwood, on the other hand, allows her dad to remain a silhouette, a blazing and symbolic force of nature. (After all, as she notes, it can be tricky to sort out the terrestrial father from the divine.) As a kind of compensation, she trains her attention on her mother Karen, the woman who caters to Greg’s windy ego and cares for the children it overshadows. Lockwood may be an absurdist, but she’s a perceptive one. Her mom serves as the memoir’s quiet heart.

Our narrator writes with playful ostentation about subjects that demand it. Of a seminarian’s search for the perfect chalice, she says: “He’s trying to choose between three or four different options, all of which are so crusted with ornament that they appear actually diseased, as if King Midas had contracted an STD and then foolishly touched himself.” And some of the details of her upbringing don’t even need to pass through a shimmering Lockwoodian metaphor to be hilarious. “Did God create the anus to be a pleasure source?” she recalls one youthful educator preaching. “Yeah. Absolutely. In His infinite wisdom, He did.” When a priest voices an offensive or misogynist idea, the author’s prose becomes suffused with pure, intense joy at his wrongheadedness. Her favored modes of critique—bemused tolerance, light mockery, perverse elation—mean that when she does sound angry or upset (a bishop “has the look of someone whom a great deal of reverent attention has been poured into for a long time,” she notes scornfully), you sit up straight.

But for all its madcap humor, Priestdaddy feels fraught with un-negotiated darkness. This makes the book at once fascinating and frustrating: Around the edges of even the silliest anecdote laps our awareness that the gleefully blasphemous narrator once attended protests outside abortion clinics and had swaths of the Bible seared into her memory. Lockwood rarely addresses her reverse-conversion head on, though she flicks at the reasons behind it in charged and elliptical passages about rape, pedophilia, hypocrisy, racism, and sexism. These sections are unfailingly powerful, and yet they never quite connect the dots between the author’s past and present. Her book jumps around in time; the scene that brings the contradictions inherent in her life story to a head refuses to arrive. You do not go from the prayerful daughter of zealots to a poet of the subversive and the obscene without a reckoning, surely. But Lockwood seems undecided about how much she wants to expose.

In that sense, Priestdaddy recalls Lockwood’s previous two poetry collections, Balloon Pop Outlaw Black and Motherland Fatherland Homelandsexuals. Those books were somehow arid and fluent at once: virtuosic and changeable and dazzling, but composed in such a way that neither the writer’s nor the reader’s emotions could quite find purchase. A Lockwood poem could remind you of a mirage of water. (“Rape Joke,” which minted her reputation as the poetry queen of Twitter when it went viral in 2013, landed so powerfully in part because it juxtaposed slick wordplay with ragged pain.) Her memoir contains more heart, but it is cautiously and equivocally proffered. The usual uproarious sentences—a regrettably appointed taco joint is “like a nightclub where people went to have wrong ideas about Mexico”—exist alongside moments of naked, un–self-conscious beauty. “Churches resemble forests in one respect,” Lockwood writes. “The light in them is filtered through something else, some live leaf.”

Priestdaddy is not coy or sugarcoated. It explores how the Lockwood women had to shrink to accommodate their patriarch. It discusses the intoxicating “we” that “closes its ranks to protect the space inside it … It does not protect people. It protects its own shape.” The book tallies the physical insults to a working-class community forced to drink uranium-contaminated water, a tragedy that may have imperiled Lockwood’s own fertility. It is ferocious in its portrait of a religious congregation’s response to sexual violence. “Many of us,” she reflects, “were actually affected, by male systems and male anger, in ways we cannot always articulate or overcome.”

But ultimately, Priestdaddy announces itself as a labor of love, an expression of gratitude to Lockwood’s parents and a celebration of their idiosyncrasies. “It was an idyll,” she says of her time in Kansas City, “of course it was an idyll. A family never recognizes its own idylls while it’s living them.” Though she clearly relishes the contrast between Greg and Karen’s piety and her own impudence—and the dramatic potential of having both forces together under one roof—the trajectory here is a homecoming, the return and reintegration of the prodigal daughter. For all the beckoning Catholic mysteries and reassurances that Lockwood has divested in order to live up to her values, she still believes in grace: “I was wonderful at endings, I thought. I found an artful and unexpected one every time. Endings sprang out of the tip of my pencils like bouquets; they were magic; they were silk and illusion; they were not earned.”

Reconciliation and connection are beautiful notes on which to conclude a family memoir. But Lockwood races to the ending, to forgiveness, before fully illuminating what must be forgiven. This makes for grace, perhaps, but not earned resolution, not literary satisfaction. She is stronger when peeling the armor off her language, both the clever acrobatics and the unconditional daughterly affection. Chapters in which she grapples earnestly with poetry as a vocation, including a gorgeous reverie on her sister’s singing voice with a gut-punch of a last line, stand out. So does Lockwood’s realization that her brand of eroticized Jesus-speak “is not blasphemy, it is my idiom. It’s my way of still participating in the language I was raised inside, which despite all renunciation will always be mine.”

Priestdaddy feels like a consecration of that mine, as if the understanding and acceptance Lockwood has reached vis-a-vis her family remains, for now, too raw for challenge. Yet the book is also studded with breathtaking examples of what she can do when she allows her guard to fall.

--

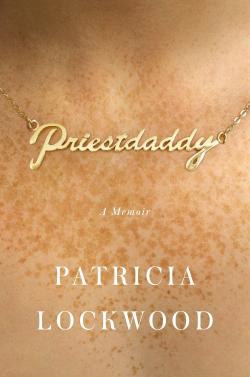

Priestdaddy by Patricia Lockwood. Riverhead Books.

Priestdaddy: A Memoir

"Consistently alive with feeling. . . Lockwood's prose is cute and dirty and innocent and experienced, Betty Boop in a pas de deux with David Sedaris."--The New York Times"You'll be wowed by Patricia Lockwood's darkly profane and poetic memoir Priestdaddy."-Elle...