Slate is an Amazon affiliate and may receive a commission from purchases you make through our links.

The Gerund That Tore a Literary Friendship Apart

The sad, silly tale of Vladimir Nabokov and Edmund Wilson’s Feud.

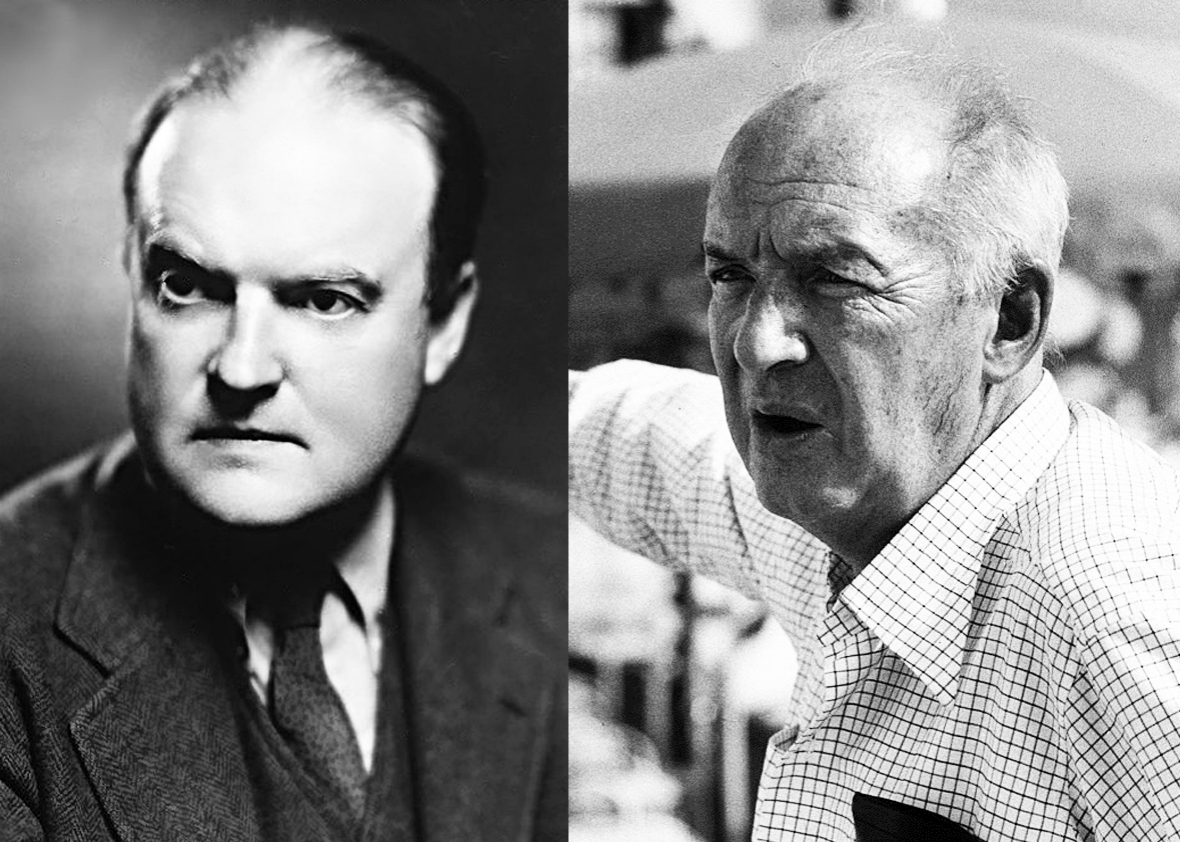

Photo illustration by Slate. Images by Walter Mori/Wikimedia and NYPL Digital Gallery/Wikimedia.

Freud called it the “narcissism of small differences,” the way people who are very much alike tend to fall out over trivialities, the bitterness of their disagreement inversely proportional to the significance of its cause. Alex Beam’s witty The Feud is about just such a quarrel, between Vladimir Nabokov and Edmund Wilson, and Beam freely admits in his introduction that when he first learned of the reason for the two literary lions’ dispute, “I burst out laughing. It was the silliest thing I had ever heard.” He never quite stops laughing through the 200 pages that follow, which is exactly what makes The Feud such wicked fun.

The eventual combatants met in 1940, when Nabokov was an obscure if well-bred recent immigrant and Wilson was perhaps the most prominent literary critic in America. As Beam points out, in time their relative fame would be reversed and Nabokov’s succès de scandale, Lolita, would make him a rich man. During those years leading up to World War II, however, Wilson, in response to a plea from Nabokov’s composer cousin, agreed to help the broke newcomer to get book review assignments and to place short stories in the New Yorker. He introduced Nabokov to his first American publisher and finagled him a Guggenheim fellowship. None of this lobbying required a superhuman amount of effort on Wilson’s part because Nabokov was manifestly an intelligent, opinionated reader and a virtuoso prose stylist, even though English was not his first language. “He is a brilliant fellow,” Wilson wrote to a friend with satisfaction. Nevertheless, Wilson was generous on Nabokov’s behalf, and they became good friends, visiting each other’s homes and exchanging a series of letters so erudite and entertaining they were later published as a book, Dear Bunny, Dear Volodya. “You are one of the very few people in the world whom I keenly miss when I do not see them,” Nabokov wrote Wilson in 1946.

The two men shared an interest in Russian history and literature, Nabokov because he was the scion of an affluent White Russian family driven out of his homeland by the revolution, Wilson because his enthusiasm for Marxism led him to spend several months in the USSR in 1935. Wilson, at least initially, believed in the Soviet regime, but Nabokov, who blamed the Bolsheviks for his father’s death (and had been set to inherit from his uncle an estate worth more than $100 million in today’s dollars), detested it. Yet this seemingly foundational difference was not what drove a wedge between them.

Instead, Wilson and Nabokov clashed over a gerund. Specifically, the Russian word pochuya, which could be translated as either “sniffing” or “smelling” when performed by a horse and might be in either the present or past tense in a line of the poem Eugene Onegin by Alexander Pushkin. This wasn’t the only Pushkin-based bone of contention between the two men, but the rest of the material they fought over was of comparable import. In 1964 Nabokov produced a translation of Eugene Onegin, a work composed of 389 stanzas of iambic tetrameter, for a nonprofit scholarly press. He appended to it 930 pages of wide-ranging and microscopically obsessive commentary. The resulting book was, in Beam’s words, “a sleek little vehicle with a Winnebago-size appendage in tow.” Wilson disliked all of it, and explained why at great length in a then-new intellectual journal, the New York Review of Books. His review is one of the most notorious hatchet jobs in American criticism.

Eugene Onegin holds a mystically central position in Russian culture. Imagine, Beam suggests, that “all of Shakespeare’s comedies and tragedies were supercollided into a narrative poem of 5,000-plus lines.” Most Russians, Beam adds, can recite Pushkin’s masterpiece from memory at “extraordinary length.” The work is also notoriously difficult to translate, although much the same could be said of all Russian literature, even the famously transparent prose of Tolstoy. (A friend recently told me that he’d shown an article featuring a dozen different translations of a single fairly simple yet beautiful sentence from Anna Karenina to a native Russian speaker. She responded that none of them could do justice to the original.) Bickering about the relative merits and flaws of various Russian translations appears to be one of those infinite, picayune activities, like 13th-century scholastic debates over how many angels can dance on the head of a pin. Because these questions can never be conclusively resolved, they invite all sides to argue them forever, becoming more and more impassioned and adamant as they continue. After a while, the sheer quantity of time squandered in the controversy generates its own fervor: This must really be worth fighting about, because we’ve been fighting about it for so long.

However, there is also plenty of subtext to the animosity that flared between Wilson and Nabokov, an antipathy having nothing to do with the exact meaning of the word nyetu or whether there’s ever an excuse to translate anything into the English word “loadened.” (Nabokov had a particularly exhaustive dictionary, Webster’s Third International Dictionary, Unabridged, from which he liked to fish out the forgotten detritus of the English language. He enjoyed pouncing on critics when they accused him of making words up.) Wilson, who could never hold onto a dime, came to resent Nabokov’s Lolita-swelled bank account and rocketing literary reputation, while Nabokov never forgave Wilson for not reviewing his own books and for praising Boris Pasternak’s Doctor Zhivago to the skies.

The weight of folly either side was not equal. Wilson insisted on putting forth his hobbyist’s proficiency at Russian as an expertise, a competition he could never win against Nabokov. Again and again, Beam describes the critic skipping out onto a limb that had broken under him multiple times in the past. Nabokov, on the other hand, was essentially mean as a snake. He might have been the superior writer to Wilson in many respects (although I, for one, remain an ardent admirer of Wilson’s criticism), but Wilson once nailed him as neatly as Nabokov pinned the butterflies that he collected: “There is also something about him rather nasty,” Wilson wrote, “—the cruelty of the arrogant rich man—that makes him want to humiliate others.” This malicious streak, abundantly evidenced in the pages of The Feud, took the form of supercilious insults directed at Nabokov’s literary rivals (not that he would have admitted to seeing them as such). Nabokov’s commentary on Eugene Onegin is peppered with such jibes, calling one Pushkin translation “execrable” and the author of another one a “toady.” This alarmed his publisher so much it hired a libel lawyer to scan the manuscript for actionable statements. Nabokov confined similarly sneering ridicule aimed at Wilson to his more private writings, until Wilson’s piece in the New York Review flushed the whole thing out into the open.

Naturally, Nabokov responded to Wilson’s pan. (“Please reserve space in the next issue for my thunder,” he wrote to the Review’s editor.) Assorted third parties got drawn onto the battlefield, including a Harvard professor Beam describes as “a personage of almost Gogolian gravamen,” Alexander Gerschenkron, to whom even Nabokov didn’t have the audacity to reply. (Also, Gerschenkron’s criticisms were unimpeachable—in the book’s second edition, Nabokov quietly corrected the errors he pointed out.) The novelist did, however, include a parodic version of Gerschenkron in his 1969 novel, Ada, one recognizable enough that the New York Times asked the professor about it. “A small man’s revenge,” was his response.

These exchanges, Beam writes, “were achingly serious and gloriously silly, catnip for editors who liked sprightly ‘knocking copy,’ as the British call disputatious texts.” Also catnip for Beam himself, who jumps in now and then to utter droll asides, like a minor comic stage character popping his head up from behind an artificial shrubbery. (In one of my favorite lines, he describes himself in 1965 “reading Boy’s Life, what the Russians would call the ‘organ’ of the Boy Scouts of America.”) Even after Wilson and eventually Nabokov himself died, other parties would resurrect the contretemps by publishing fresh reviews, articles, and letters referring to it; Nabokov’s son Dmitri stood ever-ready to prosecute his late father’s cause. “And we are off to the races again,” Beam writes when recounting yet another resurgence.

Beam believes that the roots of this absurd conflict lay in the fact that, however much their interests might have temporarily coincided, Wilson and Nabokov were simply “very different writers.” Wilson “took literature seriously, sometimes too seriously.” He concerned himself with canon-building and was a significant force, for example, in vaulting F. Scott Fitzgerald to the firmament of American letters. Nabokov, on the other hand, was the “trickster king,” a deployer of false identities, mock scholarship, puns, and puzzles, who declared, “My books are blessed by a total lack of social significance.” I’m going to beg to differ here, much as I hate to contradict my esteemed colleague or risk setting off a less considerably stellar feud. Whatever their differences as writers, Nabokov and Wilson were nevertheless writers, and anyone who’s had the opportunity to observe such creatures up close will recognize their propensity toward backbiting, envy, rivalry, shade-throwing, high-horsing, and every other variety of petty competitive behavior. The most sublime and insightful words, more often than not, emerge from decidedly ignoble creatures. You could wring your hands over the misguided senselessness of it all, but it’s saner to follow Beam’s lead and learn to laugh.

---

The Feud: Vladimir Nabokov, Edmund Wilson, and the End of a Beautiful Friendship by Alex Beam. Pantheon.

Read the rest of the pieces in the Slate Book Review.

The Feud: Vladimir Nabokov, Edmund Wilson, and the End of a Beautiful Friendship

Check out this great listen on Audible.com. In 1940 Edmund Wilson was the undisputed big dog of American letters. Vladimir Nabokov was a near-penniless Russian exile seeking asylum in the States. Wilson became a mentor to Nabokov, introducing him to every editor of note, assigning to him book rev...