Slate is an Amazon affiliate and may receive a commission from purchases you make through our links.

The Comedy of Beards

A theory.

Photo illustration by Lisa Larson-Walker. Photos by Getty Images, Library of Congress, Wikimedia Commons.

Brian Petre has a bushy, auburn beard, and he’s somewhat overweight. In other words, he’s funny. “Everything I do makes people laugh,” he says. “I used to shave every day so I wouldn’t have to deal with it, but then finally I gave in.” In the middle of 2012, Petre quit his job as a carpenter and welder for Cirque du Soleil, and set out for the Vegas Strip in a pair of aviator shades and a T-shirt. He spent the next 18 months working full-time as a Zach Galifianakis impersonator, earning as much as $150 per hour and getting flown around the country for weddings and conventions. “I’m not a hustler,” he says. “I didn’t really have to try. People wanted to laugh because of the beard, and all I had to do was finish the punch line.”

Petre’s now on break—he recently shaved, he told me, to “get some freedom from the beard”—but his industry is booming. There are at least six other chubby, bearded Galifianookalikes in Vegas, and offshoots of the same have now become a mainstay on TV. The scraggle-bearded slouch shows up in commercials as an instant, wordless joke, or he’s cast in sitcoms as the “Bearded Best Friend.” (At least four BBFs appear in this season’s batch of pilots, according to the Washington Post’s Hank Stuever, who first identified the type.) The Galifianookalike has made his name in stand-up, too: An official Beards of Comedy tour ended in 2013, and its spirit lives online, in lists of the Top 10 Funniest Bearded Comedians, the 18 Funny Bearded Guys You Should Be Following on Twitter, and many others like them.

What’s behind this comedy of whiskers? The original Galifianakis grew his beard in 2002 and made it famous in The Hangover, but beard humor long precedes the recent trend. It emerges from a deep follicle of male anxiety: We laugh at beards in part because they make us nervous. Facial hair is funny-strange; it’s a weed that grows across the borderlands of folly and fashion. For every Bearded Best Friend, there’s a Bearded Clooney, for every Galifianookalike, an urban woodsman. The beard can be a sign of girlish vanity or of manly liberation. It can be a marker or a mask; earnest or ironic; grandiose or goofy; freewheeling or self-conscious. Or it can be all of these at once.

The comedy beard points at this uncertainty. Facial hair pretends to show us who is an authentic man and who is the opposite—who’s a Hemingway and who’s a lowly lumbersexual. The Galifianookalike is both. His bold and bushy whiskers aren’t fake—he’s not in beardface—but neither is his baby fat. That’s what makes him weird and funny: He’s a bull in the body of a child.

Bearded Best Friends may have a broad and public face, but they compose just one strand in a tangled mess of irony. The others have gotten knotted up in nearly every aspect of beard culture: beard-related clubs and beard-related contests, beard rankings and beard histories, bearded sports teams, and beard appreciation days. When we talk about male grooming, we never fail to give a wink. A man doesn’t grow a moustache, he celebrates the month of Movember. A man doesn’t say his beard is manly unless he puts that word in quotes.

The wryness of a beard often mixes with nostalgia—appeals to olden times, to whiskered gentlemen and wild ’49ers, to the badass beards of yore. Our forebears were so comfortable in whiskers, so confident and true! We’re kidding when we say that, but also sort of not. Those bygone gentlemen look like they enjoyed their virile innocence, born of a time when beards were beards and men were men, when woolly bristles didn’t make us sheepish.

But that’s just a story that we like to tell ourselves, a fantasy of fallen manhood passed from one generation to the next. We’d like to think there was a time when whiskers were uncomplicated. Alas, it isn’t true. There never was a golden age of facial hair. Beards were always funny.

* * *

In October the publishing arm of the British Library put out a slim, yellow book called The Philosophy of Beards. Described by its U.S. distributor, the University of Chicago Press, as a “truly strange polemic” from 1854 that’s “[s]ure to be popular in the hipper precincts of Brooklyn,” it contains a lecture on the beauty and importance of the whiskered chin.

The volume’s author, an Ipswich muck-a-muck and chief bank cashier named Thomas S. Gowing, lays out a vigorous Victorian defense against “the unnatural custom” of the razorblade. The beard “has in all ages been regarded as the ensign of manliness,” while “the absence of Beard is usually a sign of physical and moral weakness.” His argument appeals at times to history and liturgy, dwelling on a dictum in the Bible, thou shalt not mar the corners of thy beard, that’s often cited by Hasidic Jews in support of growing sidelocks. But Gowing’s just as wedded to claims by certain doctors that beards prevent sore throats and filter filthy moisture from the air. More than that, he says, the beard provides a natural framing for the manly face, “covering, varying and beautifying, as the mantling ivy [does for] the rugged oak.”

Which is to say, the lecture is absurd, overblown, and based on faulty logic. It’s also funny. Modern readers should expect to find The Philosophy of Beards filed under “humor and comedy,” not on shelves of history or literature. Whatever its original intent, Gowing’s pogonophilic hymn has been repurposed as a novelty. At $9 for the hardcover, its promoters say that it’s the “perfect gift for the manly man in your life.”

Since the book will be given and received in jest, perhaps one needn’t worry that it’s racist. Gowing holds the white man as a paragon of beardliness and contrasts him with the smooth-faced men of certain “degenerate tribes wholly without, or very deficient.” (These latter have “a conscious want of manly dignity, and contentedness with a low physical, moral, and intellectual condition.”) Nor should readers be upset by Gowing’s fulminations on the “effeminate Chinese.” Remember that he put this down on paper just two years before the British navy launched its largely unprovoked bombardment of Canton.

There’s plenty more to make the manly man in your life a little queasy. Even a Chinaman, says Gowing, can grow some wispy strands, but the same cannot be said of women, wherever they were born. Gowing has several observations on the Lord’s decision to leave the woman’s cheek unhaired, but they all come down to this: God did not make her a hero, but “a help meet for man.” With no exploits of her own, there would be nothing for a set of whiskers to enable and ennoble.

I guess the furry humor of the beard helps to cushion this appalling bunk. Gowing’s racist, sexist ideology—that is, his embrace of since-abandoned social mores—only reinforces the notion that our love for facial hair is more sophisticated and self-conscious than our ancestors’. Irony translates philosophy into comedy, hate speech into eccentricity, a silly book into a comic object of nostalgia.

But such distancing makes it hard to see our own reflection, which also peers out from these pages. In his “truly strange polemic,” Gowing uses many of the same maneuvers that we deploy today, and one can hear in his voice an echo of the modern tone. When he offers an apostrophe to the deity of style—“O Fashion! most mighty, but most capricious of goddesses, what strange vagaries playest thou with the sons and daughters of men”—that’s not old-fashioned, it’s ironic. When he writes about “the forgetfulness of the true standard of masculine beauty of expression,” he’s indulging in the same half-serious nostalgia that motivates the denizens of Cobble Hill. When he quotes an article from 1711 that mourns the bearded Patriarchs of old, and proclaims the need to “restore human faces to their ancient dignity,” he’s digging up a nested version of the same drollery from the age of powdered wigs.

Gowing’s book was not the only jokey paean to the beard published in the 1800s. A flurry of pamphlets expressed the same ideas, with more explicit humor. At midcentury, British men could read, besides The Philosophy of Beards, articles with baiting headlines such as “The Beard! Why do We Cut it Off?” Or, more simply put: “Why Shave?” You see, a waggish fad for facial hair had taken hold during this period, and later spread with such amazing vigor that it lasted well into the 1880s.

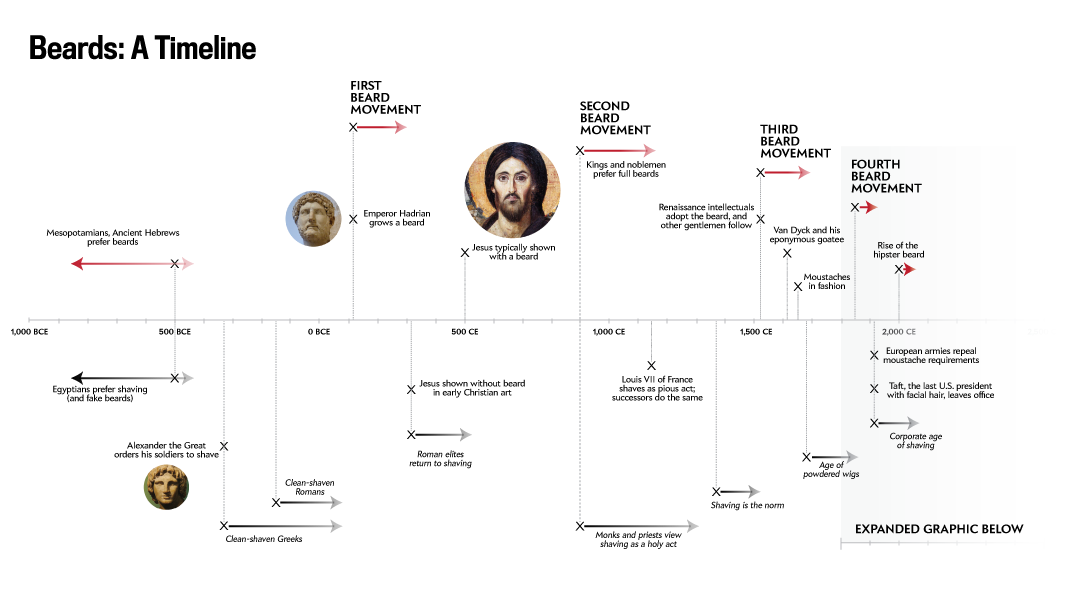

According to Christopher Oldstone-Moore, whose comprehensive history of beards—a dozen years in the making—will be published in 2015, the movement began in left-wing politics. In the early 19th century, beards were favored by radical reformers, socialists, and Chartists who wore their facial hair as a form of protest. (Hippie beards would reprise this role more than a century later.) Only after the revolutions of 1848 and their subsequent repression did the style lose its edge. Stripped of its subversive air by 1849, the beard was free to spread into the bourgeoisie and then the ruling class.

Images from wikipedia and iStock.

Images from wikipedia and iStock.

Americans embraced the trend, leading to the well-loved beards of Civil War combatants. Hair even sprouted from the chins of U.S. heads of state: The historian Sarah Gold McBride observes that between the terms of Abraham Lincoln and William Howard Taft, every president but two wore facial hair. None before or since has even dabbled in a moustache.

Victorian-era think pieces did not take the style seriously at first, says Oldstone-Moore, but they grew more earnest over time. Military men believed that beards improved their health, and some doctors shared the view. When the sociologist Dwight Robinson counted beards in pictures from the Illustrated London News, for an academic paper published in the somewhat hairy year of 1976, he found a rapid rise in whiskered men during this time. In issues of the magazine from the 1840s, beards appeared on 10 to 15 percent of male faces. In the 1870s, the fashion captured more than half of London's gents.

But even at their peak, beards reached back to imagined antecedents. They were always meant to be old-fashioned. Oldstone-Moore describes the link between an affected “bearded manliness” of the upper middle class and throwback hobbies such as hunting and mountaineering—an early wave of urban woodsmen. Those who embraced the trend did so with amusement and embarrassment, as many do today. The author Thomas Carlyle was among the loudest champions of the beard, but he only grew one on a dare. Charles Dickens dabbled in a summer beard while on tour in Switzerland, but then retreated to a moustache. (Two years later he grew it back, joking that it pleased his friends to see him less.)

So if beards achieved some gravitas, as a style fit for czars and kings, they never fully lost their sense of humor. Even back before the movement started, when facial hair stood for leftist agitation, wearers struck a familiar pose of disengagement. Oldstone-Moore briefly cites the story of a young and feisty Friedrich Engels, who in 1840 invited friends to join him in a “common moustache jubilee,” meant to horrify the members of the middle class. But even this revolt hid behind a snicker. Engels made a toast that night in a tone that sounds familiar:

Moustaches always were the pride

Of gallant gentlemen far and wide.

Brave soldiers faced their country’s foes

In brown or black mustachios.

So, in these times of martial glory,

Moustaches are obligatory.

Philistines shirk the burden of bristle

By shaving their faces as clean as a whistle.

* * *

When Thomas S. Gowing lectured on the beard, he showed his audience a set of “humorous drawings” that may now be lost to history. The reissue of his book replaces them with pictures taken from a later work on beards. That one, first published in 1922, is not a manifesto but a parody. Its title is as long and shaggy as the style that it taunts—Beaver: An Alphabet of typical Specimens, together with Notes and terminal Essay on the Manners and Customs of Beavering Men.

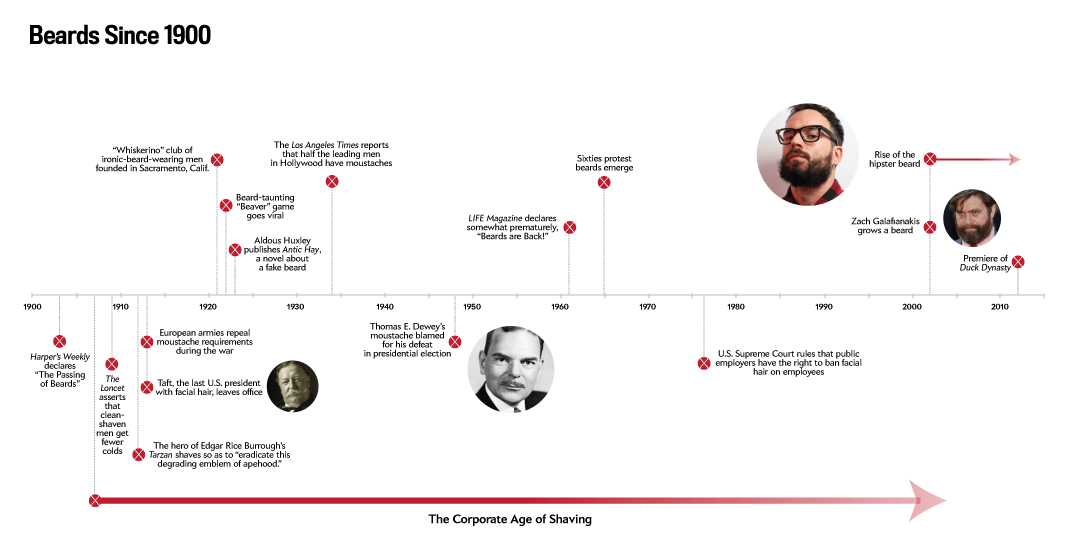

What’s a “beaver,” you might ask? A bearded man, and especially one who wears his whiskers out of style. The term appeared in the 1910s, when the fad for facial hair was paring back to shaven cheeks. Oldstone-Moore notes that by this time the medical wisdom of the beard had been overturned. A Harper’s Weekly piece from 1903, headlined “The Passing of Beards,” warns that outré facial hair “really cannot be kept clean.” A few years later, a nameless scientist in Paris (in my view he’s apocryphal) was said to have discovered “diphtheria and putrefactive germs, minute bits of food, [and] a hair from a spider’s leg” lurking in a man’s moustache. The New York Times reinforced the rumor in the summer of ’09: “MUSTACHE HARBORS GERMS: Kiss Leaves Deposit of Bacilli on French Woman’s Lips.” (For the record, jokey science has always formed a subset of beard humor. For more recent examples, see here, here, and here.)

By the early 1920s, the ridicule of beards—and thus the ridicule of beavers—had turned into a street sport. Smooth-faced undergraduates at Oxford started breaking off in pairs so they could scan the sidewalks for bushy-faced old coots. The first to make a sighting called out “Beaver!” and took a point.

No one knows when the Brits invented Beaver—or even if they did at all; some say the game got its start in Malta—but 1922 would be the annus mirabilis of jeering bearded men. Several sets of rules emerged around the central premise. One assigned 10 points for each ordinary Beaver and 50 for the red-bearded King Beaver. (A lady with a beard—the near-mythical Queen Beaver—earned 100.) Another scored the game as tennis, 15-30-45, game-set-match; misidentified Beavers were a double fault. A third, from which the images printed in the Gowing book are drawn, enhanced the game with an alphabet of scoring categories, from the uniformed Admiral Beaver to the nigh-impossible Zebra King.

The humor of beards was thus transformed from playful irony into barbed satire. Friedrich Engels’ rebellious whiskers would by this time be read as fuddy-duddy, and taken as the target for a round of arch contempt. “One may assume that the bearded are proud of their adornments, love them, cherish them, even going so far in some cases as to enclose them in silken bags before retiring to rest,” wrote the author of Beaver: An Alphabet, as if Gowing’s “ensign of manliness” were nothing more than frippery.

Let’s call this the converse state of beard anxiety, what transpires when a trend for beards recedes. As whiskered men begin to take themselves too seriously—I mean, as they lose their sense of humor—a backlash must ensue. That’s how we keep the beard in balance, and masculinity in check: If a beard is not self-mocking, we’ll mock on its behalf. Here’s the rule of thumb: A “real” man, of any age, always breaks the chains of fashion. When other, lesser men grow beards, he decides it’s time to shave; when other, lesser men are shaving, he lets his beard run wild. He’s a facial hair contrarian.

It’s curious how the figure of the beaver has prevailed in beard history and culture, not just in the 1920s but in all the decades since. He has zigzagged from each trend into the next. In the 1930s, as one cohort of bearded gents aged into their caskets, the taunting game went out of business. Its Gallic incarnation, a drinking game called Tennis Barbe, was done by ’38. Café proprietors were “seriously disturbed,” one AP reporter said, “that the bottom has dropped out of the French beard market.” In 1959, when the folklorists Iona and Peter Opie finally got around to putting out their landmark study of English schoolyard slang, they concluded that the cry of beaver had gone extinct. Their chapter on “Street Jeers” testified that modern kids would say beardie or fungus-face instead.

The beaver was so neutered in the postwar years that its major referent became a 7-year-old boy. Beaver Cleaver rose from the ashes of King Beaver. An episode of Leave It to Beaver from 1958 shows how thoroughly the meaning of the beard had been inverted: When Beaver’s brother Wally wants to feel grown up, he steals a razor for an unnecessary shave. “You know, Wally, shaving is just one of the outward signs of being a man,” his father tells him. “It’s a whole lot more important to try to be a man inside first.” In Thomas S. Gowing’s time, as perhaps today, a beard sprang forth from manly essence. In Beaver Cleaver’s, men had to cultivate their inner shave.

Unsexed but not forgotten, the beaver scampered on into the 1960s, when beards seemed best suited to the gentle people with flowers in their hair. Counterculture clothes and hair made older folks uncomfortable, since at times you couldn’t tell the boys from the girls, and beavers crawled down into a woman’s crotch. By 1969 the word widely referred not to bearded men but female public hair.

It’s telling that beards today gain currency in lockstep with a growing trend for female bush. The beavers, for their part, have found a novel habitat and another maleness panic. Consider the character of Matthew Bevers on Comedy Central’s Broad City. He’s fat, lazy, and often naked—a beardo and a weirdo. Played by John Gemberling, a prominent Galifianookalike who also serves as the Bearded Best Friend on NBC’s Marry Me, Bevers may be the model of the modern beaver.

For another spotting—10 points for me!—try an episode of Between Two Ferns, a Web show starring the original hairy man-child, Zach Galifianakis. In an episode posted in September of last year, Galifianakis sits down with Justin Bieber, whose glowing, newborn-infant skin look as if it would melt a beard on contact. Midway through the episode, the host erupts in unexpected rage, his face turned tantrum-red. Half-baby and half-brute, Galifianakis starts whipping Bieber with a belt.

Here’s the apogee of beard-based humor-panic in the 21st century: A hairy, sexless man assaults a hairless sex symbol, using a tool of discipline that harks back to bygone days of bearded, male authority. “You’re not a child, and that’s the point,” Galifianakis stammers. “I can hit a grown man with a belt!”

The joke offers some catharsis to certain brohans of today, who dismiss the fresh-faced Bieber as “that fag” or else turn the game around and call him “Justin Beaver.” But who’s the bigger beaver here, and who’s the bigger man? Which cult defines the future of masculinity—that of the rock star or the lumberjack? As usual, the comedy beard can’t sort out these layered meanings; it only points them up.

* * *

Since the beard has always been a marker of both authenticity and its opposite, we must not neglect a vital piece of whisker marginalia: the fake. It isn’t clear to me if men ever wore fake beards, or if they ever wear them now, but the notion of a man pretending to his bearded manliness has inspired countless accusations, if not mini-panics. The falsie makes the case against the beard explicit: It shows the growth to be a stand-in for a wig.

I’m sure that every efflorescence of the beard drags along the frantic claim that some are fake. Two months ago we saw the specter of the “beard weave.” It’s just a man-merkin, cried Vulture, referencing a time when fake beards applied to lady-beavers. “Never, ever, get a beard weave,” advised GQ. But like everything about the beard, we’ve seen this all before. During a slight uptick of beardedness during the early 1960s, perhaps riding on the Civil War Centennial, the AP described “a strange new craze” of glued-on facial hair. Young men do not wear these as a joke, advised an essayist in Life, “but as a dead-serious effort to impress people, particularly young ladies.” Note the object of his scorn: not the fraud itself, but the lack of beard-related humor.

Back in 1923, when kids still played beaver in the streets, Aldous Huxley devoted several hundred pages to a bogus beard. His novel Antic Hay describes a postwar nebbish, “melancholy and all too mild,” who transforms himself with shoulder pads, a sturdy cane, and a fan-shaped beard applied with spirit gum. “The proportions of his face were startlingly altered,” Huxley writes, such that he became “the complete Rabelaisian man. Great eater, deep drinker, stout fighter, prodigious lover; clear thinker, creator of beauty, seeker of truth and prophet of heroic grandeurs.” When in this getup he finds a lady on the corner of Queen’s Road, he tries this epic pickup line: “If you want to say Beaver, you may.”

The fashion beard raises the specter of the “false beard.” (Data drawn from Google Books.)

Such disguises offer just one version of impostor, the literal kind. More disturbing to beard culture, though, and somewhat harder to discern, are those men who use real facial hair to fake out a social norm. In the 1980s, when beards were mostly out of favor, some men adopted them as badges of an emerging gay identity. “It’s the hyper-masculine approach,” says Oldstone-Moore, who devotes a chapter of his book to gender-bending trends in facial hair. “Bears go for outdoorsy, bushy beards. Leathermen go for the biker look.”

Then, like beavers did before, the fake beard spawned a female type, this one purely notional—just the word itself, a “beard,” in quotes. According to gay lingo of the ’70s, a man’s beard could be his wife or girlfriend. She was still, per Gowing, a “help meet for man,” but now she helped to hide his gayness and cover up the missing manliness within.

Check the paradox: The beard expresses manhood even as it hides the man. Thomas S. Gowing used both sides of this equation in his manifesto. The beard, he said, projects as it protects; it shows a hero’s valor and shades his neck from injury. But The Philosophy of Beards may well have been a kind of beard itself. In spite of Gowing’s bold assertion that “ladies by their very nature like every thing manly,” and, quoting Shakespeare, that a shaven husband is only fit to be a “waiting-gentlewoman,” he never put his own beard to use in matrimony. An obituary printed in the Ipswich Journal, and provided to me by the historian and classicist Maurice Whitehead, describes a bachelor of 67 years who “took an especial interest in young men, and was ever ready to advise and assist [them].”

Did Gowing’s love for beards cover up a love for boys? Oh, I don’t know. What’s more apparent and more telling is the way his sense of humor covered up a sense of shame. That’s not unique to him, but fundamental to his beard. For an interest in male grooming to pass as something manly, we temper it with jokes. That’s how it’s always been, and how it is today. The comedy of beards becomes a closet for our dress-up games. It’s the hairy man’s “no homo,” and the very thing it mocks. O Irony! thou truly art the beard of beards.

One more thing before we’re done. That obituary of Thomas S. Gowing furnishes another fact worth sharing. This is not a joke: The “S.” stands for “Shave.”

---

The Philosophy of Beards, by Thomas S. Gowing. British Library.

See all the pieces in this month’s Slate Book Review.

Sign up for the Slate Book Review monthly newsletter.