Slate is an Amazon affiliate and may receive a commission from purchases you make through our links.

Last Kind Words

Lost 78s and the insular world of music obsessives.

Photo by Bret Stetka

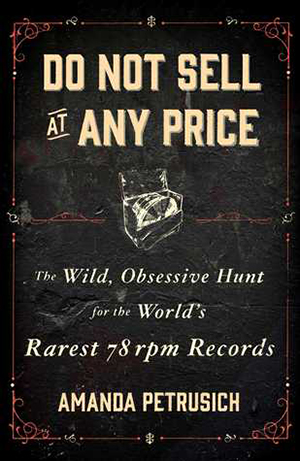

The most important thing that collectors would want me to take away from reading Amanda Petrusich’s fascinating book Do Not Sell at Any Price: The Wild, Obsessive Hunt for the World’s Rarest 78rpm Records is that collecting 78s has no relationship to collecting LPs or 45s. If you own a rare LP, it is still comparably common, while a rare 78 might be the only one anywhere in the world. As Petrusich puts it, “The distinction is acute, comparable to collecting pebbles versus collecting diamonds.”

However, the entire time I was reading this captivating book, I couldn’t help but notice the similarities. And while the adrenaline rush that comes from holding a great record is definitely part of the appeal, it seems as though for most collectors it’s less about the score and more about the music. Petrusich describes collector John Heneghan’s experience of holding a rare record in great detail, but it’s “placing it on his turntable and releasing the needle into the groove” that leaves him “feeling transported, feeling changed.” I go through that exact same process and feel those exact same things every time I write a review for my blog My Husband’s Stupid Record Collection, a collection that doesn’t include a single 78rpm record, so maybe this distinction isn’t so acute.

But the way that 78s are nothing like LPs has to do with the music recorded on them. 78s are often the only remaining example of a recorded song. Since metal masters were usually not made of 78 recordings, as Petrusich puts it, “if the records themselves break, or are crammed into a flood-prone basement, or tossed into a dumpster, then that particular song is gone, forever.” It took a couple of chapters to really sink in for me. But think about that for a second: There are amazing songs out there that no one living today has ever heard, or will ever hear.

Whether you’re already a 78 aficionado, a casual record collector, a crate-digger, or just someone like me who enjoys listening to music, you’re going to love this book. Learning about rare 78rpm records takes Petrusich on a journey well beyond junk shops and musty basements. What’s it like to navigate a giant flea market and interview ornery old men who have been collecting 78s since the 1950s? A highlight of the book is the moment when Petrusich learns how to scuba dive in order to hunt for 78s that may or may not be on the bottom of the Milwaukee River. She is not a thrill-seeker, and she realizes the time and money she will have to sacrifice just to learn how to scuba dive, but Petrusich gives in to the hope that whatever she finds might just be a little piece of lost history. Ultimately, this is an adventure story.

The world she wades into in this book is almost exclusively composed of men, and reading this account of American musical history from a woman’s perspective made me love it even more. Petrusich writes about her experiences as a woman working in the male-dominated field of music writing. I particularly related to her description of forcing herself to “learn the language of criticism”—memorizing models of guitars and obscure labels even though it felt depressing and hollow. She writes:

I was methodically teaching myself exactly how to miss the point. When I wondered whether I just listened differently—whether my experience of music was somehow more emotional, more divorced from its technical circumstances, more about the whole than its pieces—I chastised myself for being arrogant or stupid. (I blanched, in fact, at catching myself using a word as treacly as “emotional.”) And yet: I could love a record more than anything in the world and still not make myself recall its serial number.

In February, I started My Husband’s Stupid Record Collection, where I decided, as an average music listener and music fan, to go through each of the 1,500 or so records in my husband’s personal collection and write about each one. I’d never written about music before, so I just went with my gut and wrote stream-of-consciousness style about how the music was making me feel. I wasn’t following the rules about how you’re supposed to write about music, but people were connecting to it, and suddenly I had picked up thousands of readers. To my surprise, though, a small but very vocal group of women tried to shout me down: What I was doing was sexist since I was writing about my husband’s record collection and not my own. I was making it harder for female cultural critics. The only reason men were reading it was because I came off as naive or stupid.

My writing wasn’t about the context or the history of the music because I didn’t know the context or history of the music. I was picking up the vocabulary of records (LP vs. EP vs. 45, gatefold, liner notes) as I went along, and I honestly have no interest in learning “the language of criticism.” Traditional music criticism doesn’t really resonate for me, so if I was going to write about records, it was going to come from a place that interested me: The way the music made me feel. Petrusich keeps coming back to this point in Do Not Sell at Any Price:

There’s no wrong way to enjoy music, and I understood that certain contextual or biographical details could help crystallize a bigger, richer picture of a song. But I continued to believe that the pathway that allowed human beings to appreciate and require music probably began in a more instinctual place (the heart, the stomach, the nether regions). Context was important, but it was never as essential—or as compelling—to me as the way my entire central nervous system involuntarily convulsed whenever Skip James opened his mouth.

I put a big star in the margin next to that paragraph. Petrusich was articulating my exact argument, and she was saying it about 78s. These obscure and precious songs are hard to get your hands on, and then it’s even harder to learn about the context behind them. And yet, whenever Petrusich put one on, she would have that same gut reaction that I had when I listened to Black Sabbath’s Paranoid or the Buzzcocks’ Singles Going Steady: a natural high that came from a completely instinctual place. That’s what kept her hunting for these 78s; that’s what keeps all these fanatical collectors forever on the hunt; it’s what keeps me listening to and writing about music.

Petrusich eloquently balances her emotional reactions to the music she’s discovering on 78s and the history she’s learning. For example, there’s the Jazz Record Center, a long-defunct record store that once existed on West 47th Street in Manhattan. Opened in the 1940s, it was one of the first places where 78rpm record collectors could meet and be outsiders together. She also writes about the legend of collector Harry Everett Smith, who compiled The Anthology of American Folk Music, curated exclusively from his personal 78 collection. Known for chewing peyote, Smith was eventually appointed “Shaman in Residence” at the Naropa Institute, now Naropa University, in Boulder, Colorado.

Petrusich’s writing is elegant and witty; I laughed out loud several times and felt like Petrusich and I could be friends. And the next time I’m at a big rambling flea market or antique store, I’m going to know just where to look for an old 78; after reading this book, I might even know if it’s valuable or not. I’m not going to tell you how to do it, though. Pick up this book to find out, and maybe we’ll bump into each other wearing scuba gear at the bottom of the Milwaukee River.

---

Listen to Sarah O'Holla discuss her blog My Husband's Stupid Record Collection on Slate's The Gist:

Do Not Sell at Any Price: The Wild, Obsessive Hunt for the World’s Rarest 78rpm Records by Amanda Petrusich. Scribner.

See all the pieces in this month’s Slate Book Review.

Sign up for the Slate Book Review monthly newsletter.