Slate is an Amazon affiliate and may receive a commission from purchases you make through our links.

A 24-foot Panorama of the Most Infamous Day of World War I

Joe Sacco annotates his monumental new book, The Great War.

|

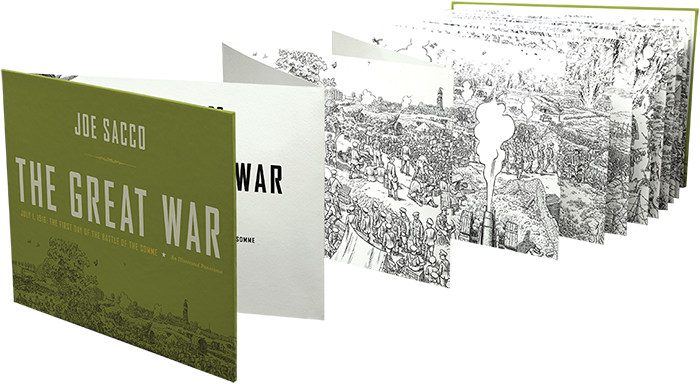

Joe Sacco annotates The Great War The comics journalist Joe Sacco's new book The Great War tells the story of July 1, 1916—the first day of the Battle of the Somme, one of the bloodiest days in human history—through a single, astonishing panorama, 24 feet wide and containing thousands of human figures. Here Sacco annotates a small part of this epic undertaking, a tableau several inches wide. Continue » |

Joe Sacco annotates The Great War

The comics journalist Joe Sacco's new book The Great War tells the story of July 1, 1916—the first day of the Battle of the Somme, one of the bloodiest days in human history—through a single, astonishing panorama, 24 feet wide and containing thousands of human figures. Here Sacco annotates a small part of this epic undertaking, a tableau several inches wide.

Tap for full image

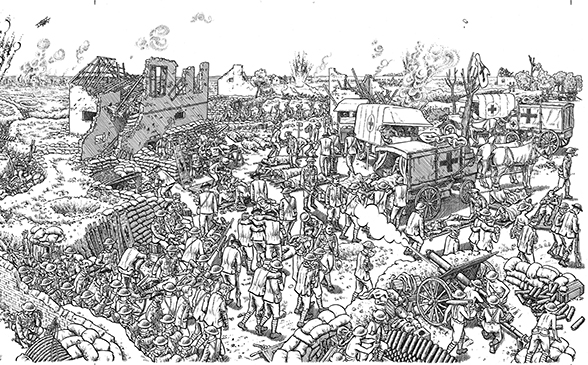

Here the walking wounded are making their way back to a casualty clearing station in the rear areas. There are numerous pictures of this sort of thing at the Imperial War Museum in London, where I spent some days poring over its enormous photo archive. The museum has photos of almost every imaginable facet of the First World War, and I photocopied hundreds of images and tried the patience of the museum's staff with my frequent requests for more paper, more toner, and help when the copy machine broke down.

The official photos of the wounded are sometimes grim; some of the men are obviously traumatized. But official photos seldom show grave injuries. The majority show lightly wounded soldiers relieved to be alive and smiling for the camera. When you are drawing, the soldiers have no camera to smile at.

This is an advanced dressing station, just beyond the trenches but still within range of German artillery. Some immediate medical care was provided here, and these casualties would have probably needed evacuation by ambulance. I show soldiers who've died and others who are waiting for transport. A detail like the medical orderly cleaning a soldier's wound was garnered from a photograph.

Some of the stretchers were attached to wheels. Here a stretcher bearer pushes a casualty to the advanced dressing station. I saw photos of wounded soldiers with makeshift splints so I gave this fellow one.

Here I show casualties being loaded into a horse ambulance with motorized ambulances right behind. Julian Putkowski, a World War One historian whom I met in London through a lovely bit of serendipity—the brother of the woman I was staying with happened to be his next-door neighbor—impressed upon me how much horse power mattered to the armies of the time. I am not particularly good at drawing horses so this news distressed me. I found pictures of horse ambulances at the Imperial War Museum, but I needed a lot of reference material to get this particular vehicle right, particularly the mechanics of its axles and how the braking system fit around the driver's seat.

Drawing so much machinery as precisely as possible was always a "challenge," as they say. I felt I had to show a range of vehicles, and not just the ones that were easiest to draw. My biggest worry was inserting something that was introduced later in the war by mistake so I spent more time than I'd like to admit trying to determine when what truck or howitzer made it to the front.

I don't show the Germans fighting the British in the illustration. I wanted to emphasize the remote nature of the war, how artillery and machine-gun fire could destroy wave after wave of soldiers without the enemy being seen. The only Germans I show are a few prisoners whom I've depicted just as bedraggled as their captors. Here a couple of German soldiers have volunteered or been pressed into helping with the wounded. There are numerous photos, even by official photographers, of German and British wounded interacting, lighting each other's cigarettes, and aiding each other in getting away from the front. Many of these are quite moving, but I imagine they don't tell the whole story. Elsewhere in the illustration I show some British soldiers' anger toward the prisoners, which was expressed in certain first-person accounts I read of this and other First World War battles.

This man has a tag tied around the button of his tunic pocket on which a medical orderly would have written some basic information for the next attendant up the medical chain.

Putkowski, the historian, also gave me to understand that many men smoked, and pipe smoking was very much in vogue then. This is borne out in numerous photos taken during the war. I basically tried to show as many men smoking pipes as smoking cigarettes. Tobacco is one of the primary staples of war. In my travels to Bosnia during the conflict there, people were puffing away like chimneys. School teachers and soldiers were sometimes paid in cigarettes. In war it's a basic necessity, like food.

The war goes on. Here we see an 18-pound field gun in action. Besides the photo references I collected for this artillery piece, I got good pictures from multiple angles of an example that is on display at the Imperial War Museum. As far as the positions of the artillerymen, I watched old film of the gun firing on YouTube. I had to freeze the frame on the video to see how far back the barrel went back after each shot. The men on opposite sides of the barrel remained on their bucket seats when the gun fired, which surprised me, but this was a quick-firing weapon. Numerous photos showed artillerymen bare-chested and with their suspenders dangling. Obviously, it was hot work.

---

The Great War by Joe Sacco. Norton.

See all the pieces in this month’s Slate Book Review.

Sign up for the Slate Book Review monthly newsletter.