Slate is an Amazon affiliate and may receive a commission from purchases you make through our links.

All Children Are Heartless

The girl who invented Fairyland—and the books she’s not writing for children, exactly.

Illustration by Peter Bagge

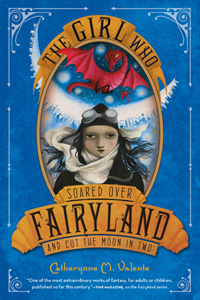

The third book in Catherynne M. Valente’s Fairyland series, The Girl Who Soared Over Fairyland and Cut the Moon in Two, comes out this month, adding another volume to the award-winning series, which critics have praised for its ambition and imagination, as well as its odd, dark beauty. The Fairyland books follow a girl named September who journeys to Fairyland, encountering wonders, making friends and enemies, and saving Fairyland—most often from itself. Time’s Lev Grossman described the series as “one of the most extraordinary works of fantasy, for adults or children, published so far this century.”

But in conversations with other writers and editors, I’ve heard the books described as “inscrutable,” “too challenging for middle grade,” and “simply not for kids.” In the New York Times, Marjorie Ingall called the series “exhausting” and “ill fit for the publisher’s target audience.” And it’s true that Valente does tend to attract an older crowd of readers. At a recent Community Bookstore appearance in Brooklyn, the majority of her audience was twentysomething lit geeks whose questions for Valente were focused on her feminist outlook and background as a classics major.

Few would argue that there’s anything wrong with a challenging middle grade book—some might claim that Fairyland is popular because it’s challenging. But I suspect that the reason these detractors have difficulty categorizing the Fairyland series is because Valente is not trying to write middle grade fiction at all.

At the series’ start, the protagonist September is a keen and clever 12-year-old. This third book, The Girl Who Soared, begins with September at 14, worrying that she’s too old to return to Fairyland. But away she’s whisked nonetheless, to stop the disruptive moon-yeti Ciderskin from shaking the moon into pieces. She is joined by her friends from the previous books—the blue marid Saturday and the “harooming” wyverary A-Through-L (part wyvern, part library). Though their adventures are exciting enough, the book’s thematic core is September’s vulnerable adolescent state, and her future in Fairyland. Readers have seen her grow from a “Somewhat Heartless” preteen to a girl with a “new, red” heart, a heart that’s a “heap of tender and terrible wonders.” It is September’s heart that she fears will give her away in situations where she’d rather be “knowing and canny”—and which she also fears will get her kicked out of Fairyland.

This business about September’s heart is one of Valente’s most consistent nods to the classics of children’s fantasy. In the series’ first book, The Girl Who Circumnavigated Fairyland in a Ship of Her Own Making, we are told quite matter-of-factly that “all children are heartless.” September, being somewhat grown already, is only Somewhat Heartless. This notion is lifted straight from J.M. Barrie’s Peter and Wendy, the 1911 novel that most now simply call Peter Pan. The novel’s final line:

“Every spring cleaning time, except when he forgets, Peter comes for Margaret and takes her to the Neverland. … When Margaret grows up, she will have a daughter, who is to be Peter’s mother in turn; and thus it will go on, so long as children are gay and innocent and heartless.”

Returning with the seasons, growing up, and heartlessness are as integral to Fairyland as they were to Peter Pan, and just as emotionally resonant. The reference and its prominence in September’s story reads like a clear gesture of respect from Valente to Barrie for what he was able to accomplish. He created a novel for children that did not shirk from emotional complexity. Valente uses the familiar formula of Victorian children’s novels such as Alice in Wonderland and Peter Pan, coupled with a decidedly arch Victorian tone. Playing within the bounds of this structure, she then creates a mishmash. Enter Greek mythology, epic poetry, folk legends, and fairy tales. She folds in nods to various cultures’ hero stories in order to complement and complicate the familiar Victorian form, and also takes the time to unpack and question certain elements of these classic books that she finds troubling.

Writing on John Scalzi’s Whatever blog last year, Valente stated that the impetus behind her writing is to take “the tropes of fairy tales and quests and folklore and portal fantasies and old school children’s books. Add complexity. Add emotional crunchiness. Add poking with a big stick.” Valente subverts her own referential formula by allowing this “emotional crunchiness”—complicated, frank interiority—to darken the books’ plot developments and characterizations.

For instance, in the climactic moments of the first Fairyland book, 12-year-old September meets a character who also stumbled into Fairyland accidentally, through an armoire. The character describes living a full life, even having a family, in Fairyland, and then waking up as a child again in her father's old coat closet. Valente's deliberately referencing the end of The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, the second of C.S. Lewis’ Chronicles of Narnia. The Pevensie children, grown up as kings and queens in Narnia, chase a stag straight through the wooden doors of the wardrobe, and find themselves children again in wartime England, in the same place where they began the novel. They haven’t got much to say, aside from the suggestion that they find the Professor, their guardian, to tell him about their adventures.

Winter Tashlin

Valente, it seems, isn’t satisfied with this lack of “crunchiness.” Though there’s much to chew on, the Pevensies don’t bite. Valente’s character recounts a very different reaction to returning to the world:

“I woke up in my father’s house, curled inside the armoire, as though no time at all had passed. … But oh, how I remembered it all! … I screamed in the armoire. I kicked the wooden walls in, trying to get back. I cried as though I were dying.”

This moment alone is enough to convince me that a merely satisfying middle grade adventure is not what Valente’s interested in writing. Her references and writing style are intentional, counting on nostalgic older readers to recognize them, or at least find them tonally familiar. Where she draws contrasts between that comforting familiarity and her moments of “emotional crunchiness,” where she inserts more honest emotional range, is where older readers are being asked to reasses their notions of what children’s literature was, is, and can be. While a younger reader will certainly identify with this character’s woe, Valente is as much a scholar as an author, as interested in examining and reinventing children’s literature as she is writing a good story.

The emotional crunch of book three, The Girl Who Soared Over Fairyland and Cut the Moon in Two, is September’s worry that her Persephone visa, which allows her to return each spring to Fairyland, will soon be null and void. Valente’s imagination for whimsical locales in this series reaches a pinnacle with this book, as we follow September to a highway in the stars, a moon-city that grows along the swirling insides of a giant shell, and a lightning jungle that crackles with electricity. But the Fairyland books are not about Fairyland itself—its wonderful locations are merely colorful backdrops for September’s transformation from a Somewhat Heartless 12-year-old into a complex 14-year-old. And despite the presence of beloved characters from earlier novels, The Girl Who Soared is an adolescent’s tale, full of raw emotion, unabashed wonder, and touching uncertainty.

September, like any adolescent, must face the future, and what she sees confuses and frightens her. Because of a series of run-ins with her friend Saturday, a blue-skinned boy who lives outside of the chronological order of time, September has come to believe that her fate has been written for her. Her fate seems as inevitable as the fact that she must grow up, and while she wishes to become all sorts of things that she knows grown-ups to be—“cool and collected” as well as “big enough to hold on to everyone she loved at once”—she believes that growing means giving up the spontaneity of her current adventures, and the freedom to make up her own mind about herself: “I have read books, so many books,” she laments, “and I know that growing up means you can’t keep going to Fairyland the way you did when you were a child! Something happens to you and suddenly you have to keep a straight face and a straight line!”

Once the encounter with the moon-yeti is over and the adventure must end, September’s choices for herself are what lift The Girl Who Soared out of the realm of the traditional children’s fantasy novel. I don’t think you’d forgive me if I told you what that final move is, but the books September’s read that make such bleak distinctions between children and adults don’t dictate what’s in store. “Grown-Ups … use their hearts to start their story over again,” the narrator whispers to September in a satisfyingly meta moment, implying that September, like Valente herself, isn’t beholden to the rules of the genre—she can write her own fate. Young readers will be encouraged to hear that growing up does not have to mean the end of adventure. So will adults.

So perhaps it’s true that Fairyland is “simply not for kids.” Or rather, the books are not simple, and not simply for kids. They’re for readers: smart children, and adults who remember the books that had an effect on them in their youth. They’re for lit geeks, both existing and in the making. But as for the question of being an “ill fit” for the middle grade audience, I will leave you with this, oh patient reader. At that same reading this past spring, populated by grad-student types like me, there was another faction present. Up at the very front, crouched on the carpet and leaning against the lowest shelves, sat a fair number of youngsters, clutching hardcover copies of Valente’s books. While many of us wanted to hear how much the series was inspired by Joseph Campbell, these smaller audience members had a much more pressing question. Would their favorite character—A-Through-L the wyverary, a bright red fireball of joy—be in Book 3? For heartless little children, they seemed very earnestly concerned.

---

The Girl Who Soared Over Fairyland and Cut the Moon in Two by Catherynne M. Valente. Feiwel and Friends.

See all the pieces in this month’s Slate Book Review.

Sign up for the Slate Book Review monthly newsletter.