Slate is an Amazon affiliate and may receive a commission from purchases you make through our links.

Blane and Andie, 25 Years Later

Andrew McCarthy’s memoir and Molly Ringwald’s novel suggest how hard it is to love like characters in movies.

When Andrew McCarthy rushed up to Molly Ringwald in the final moments of Pretty In Pink to apologize for being a douchebag and declare his love, it seemed, to many of us growing up in the 1980s, the pinnacle of romance. “I always believed in you,” his Blane tells her Andie, blue-gray eyes brimming with nervous conviction. “I just didn’t believe in me.”

Swoon. If only we can get there, we all thought. Everything will be perfect.

Alas. Andie and Blane will forever stay locked their youthful embrace, O.M.D.’s “If You Leave” soaring on the soundtrack. But for the rest of us, life marches cruelly on, one messy heartache after another, and a future in which we ever get to do it on a cloud without getting pregnant or herpes seems increasingly dim. Even for Andrew McCarthy and Molly Ringwald, who each have new books out about relationships that are less than movie-perfect.

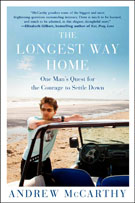

When we catch up with McCarthy at the start of his memoir, The Longest Way Home, it’s been 26 years since he answered a fateful newspaper ad seeking a boy, “eighteen, vulnerable and sensitive.” Since then he’s been through some shit: Rehab, a wrenching divorce, a spate of Lifetime Original Movies. Just to name a few.

But these days he’s working steadily as an actor and director, and, to seemingly everyone’s surprise, has made a side career for himself as a travel writer. (“You’re an actor,” the befuddled editor of National Geographic Traveler says at their initial meeting.) His relationship with his ex-wife has mellowed into an agreeable custody arrangement for their son, and he’s living in harmony with a sunny Irish girlfriend, D, and their young daughter. Seven years went under the bridge, like time was standing still. (Sorry.) All has been well.

But now, D wants to get—gulp—married. “The best thing that you could do is show up,” a friend tells an uneasy McCarthy, who swallows his fear and agrees to the ceremony. But then a funny thing happens. As D starts planning the wedding, McCarthy loads up his schedule with trips to far-flung places: Patagonia, the Amazon, Mount Kilimanjaro. “You do understand that as soon as we decided to get married you’re going as far away as you can get,” his fiancée tells him, leading the way toward an aha moment with all the originality and subtlety of a cartoon light bulb.

McCarthy, it turns out, is—wait for it—afraid of commitment. His reticence has to do with a bunch of things: His overbearing father, who has an uncannily Hughesian manner of speech (“No son of mine is going to be a fucking thespian”); his first marriage, which he found stifling (“I felt like I had to leave 20 percent of myself outside just to walk in the door of our marriage.”); and a (sensitivity-based?) awkwardness that has long caused him to regard himself as a “loner.” There’s more, too. Lots more. And the only way for him to work through it and become a better man, of course, is to set forth on his planned journey—“not to escape the commitment I recently made,” he tells us, “but to gain the insight necessary to bring me home.”

Cue “Desperado” as McCarthy heads off a journey of self-discovery, one that involves much staring into the middle distance, licking of ancient filial wounds, charged but chaste interactions with women with “ample breasts,” and of course, pizza. Specifically: “Papa John’s quatro queso pizza at six-thirty in the morning.” Morning pizza! The taste of freedom! It’s a sensitive-yet-vulnerable man’s rumspringa interrupted only by the occasional pang of conscience.

Often, a sudden recollection of responsibilities back home falls down on me hard, like a burden I’ve neglected that needs my attention. Feelings of guilt and affection, resentment and love, will often vie for dominance in my suddenly addled mind, but tonight, retrieving my bicycle and pedaling along the dirt road to my bungalow by the sea under a dripping gauze of stars...

Ugh. McCarthy’s editor had it right: He’s not a writer, he’s an actor. That said, the observational skills he’s developed in his primary career are useful when he’s describing the characters he meets on the road, who come alive with just a few gestures, like that editor, “a barrel-chested lion of a man with a mane of silver hair” who agreed to meet him at an East Village bar but clearly didn’t take him at all seriously. “Can you even write?” he asks McCarthy, “looking at a young woman down the bar.”

Courtesy Simon & Schuster.

Unfortunately, most of McCarthy’s observations are focused on himself, and his examinations of his own ambivalence are about as interesting as a stoned person’s description of a rug pattern. “Getting married would be an acknowledgement of who I am rather than clinging to what I had,” he thinks at one point.

On the other hand, I’m an accumulation of all my past, and if in getting married I leave it behind, I don’t know what I take forward. If I let go of my past, I’m uncertain what I have to offer. If I’m not that person, then who am I?

At this point, I’d have flown to the Amazon just to strangle him. McCarthy’s publisher is billing The Long Journey Home as a male version of Eat, Pray, Love, and it’s possible that McCarthy’s long, lonely trek around the world will fulfill a similar kind of wish-fulfillment fantasy for some men. For the rest of us, a story about a man-child who feels trapped and underappreciated by his family and just wants five minutes to himself is joyless and familiar, like watching a Judd Apatow movie with all of the poop jokes cut out.

There’s a creepy self-congratulatory undercurrent to these kinds of narratives. Like we’re supposed to be grateful to guys like Andrew McCarthy for laying bare their feelings, for telling us, finally, how it really is. You’ve been asking about my feelings for years! Well, here they are! [Hands you a bag of shit.]We’re supposed to applaud them for choosing to be vaguely decent, after long, noble struggles against primordial dickishness . But it's hard to empathize with McMcarthy when he's just … being a dick. Witness the scene in which he's tasked with buying groceries for his girlfriend’s visiting family, and, sent out into the streets of Vienna, finds few stores that are open on a Sunday. “The burden of having to provide for these people began to swell up inside me and I wished I were there alone. … I wished I had no contacts or ties. I loved my children, but the rest of them—the hell with it!”

Remember: He just has to buy bread.

It’s gratifying when someone finally calls him on his bullshit. “Will you stop being an asshole?” a friend finally says. This should have been the title of the book. The question may never be truly answered to the reader's satisfaction, but a cinematic moment set atop snowy Kilamanjaro, where the group is passing around a satellite phone they’re using to send messages home, suggests he finally sees the light. Another climber reveals he has no one to contact, and McCarthy is

brought up short. Trying to carve out space for myself, often traveling to the ends of the earth to achieve it, wishing I had no responsibility, yearning for total freedom, and here is someone with just that, unattached, with endless space surrounding him, and my feeling isn’t one of envy or wistfulness. I don’t yearn for what he doesn’t have.

And of course, in the end, McCarthy does show up to marry his girlfriend. He’d always believed in her, it turns out, he just didn’t believe in him.

There’s a self-centered man-child at the center of Molly Ringwald’s debut novel-in-stories When It Happens to You, too which catalogues one couple as they plod through the five stages of grief that come after the husband's infidelity. Written in a spare, semi-detached way—like a trauma victim spitting out details of a tragedy—it suggests Ringwald, too, has been through some real shit since graduating from John Hughes high school. Her second husband, a book editor, may be the reason her prose is so sharp, but let's hope he's not her inspiration.

We know Phillip is cheating on his wife, Greta, from almost the first page, well before Greta herself finds the evidence in an email and makes him tell her all of the gory details down to the color of his mistress’s pubic hair. We know because Phillip is acting like a dick—remote and snappish. By the time we hear his side of the story, his guilty conscience seems to have driven him to the idea that his infidelity isn’t his but his wife’s fault. If it weren’t for her demands—wanting him to stay home for dinner, wanting to have a second child, wanting him to act like a fucking grown-up—he probably wouldn’t have ever taken up with the 19-year-old piano teacher. If only she had appreciated him!

She wanted him, he told Greta in one of the most raggedly honest moments of their marriage, during the brief pause before she closed her heart to him. The girl wanted him and that had been enough.

Photograph by Fergus Greer.

Of course broken hearts don’t really “close.” Greta and Phillip's wounds stays open, and radiate pain to everyone close to them, from their daughter to the next man-child who falls in love with Greta, the pot-smoking star of a children’s television program whose heart Greta coolly stomps with a transgression of her own. But Ringwald is thoughtful about the difference between Greta’s betrayal and her new role as betrayer: “She felt a discomfort that she supposed to be the weight of her guilt, but that was all. It was nothing like what it had felt like to be the one deceived. … The quality of betrayal is commensurate only to the measure of love for the one you betray.”

Although they recently exchanged promotional Twitter messages, Ringwald and McCarthy are, per McCarthy’s book, not in touch. So it 's just coincidence that both of their books end with chastened, changed men returning to women, and come to a similar conclusion, which is that real, imperfect relationships are more satisfying than a lifetime spent chasing John Hughes moments. Maybe O.M.D. said it best: “We’ve always had time on our sides, but now it’s fading fast. Every second, every moment, we’ve got to make it last.”

---

The Longest Way Home: One Man’s Quest for the Courage to Settle Down by Andrew McCarthy. Free Press.

When It Happens to You: A Novel in Stories by Molly Ringwald. It Books.

See all the pieces in this month’s Slate Book Review.

Sign up for the Slate Book Review monthly newsletter.