Slate is an Amazon affiliate and may receive a commission from purchases you make through our links.

Making Comics After Mauschwitz

-

© 2008 by Art Spiegelman; reprinted with permission of the Wylie Agency, LLC.

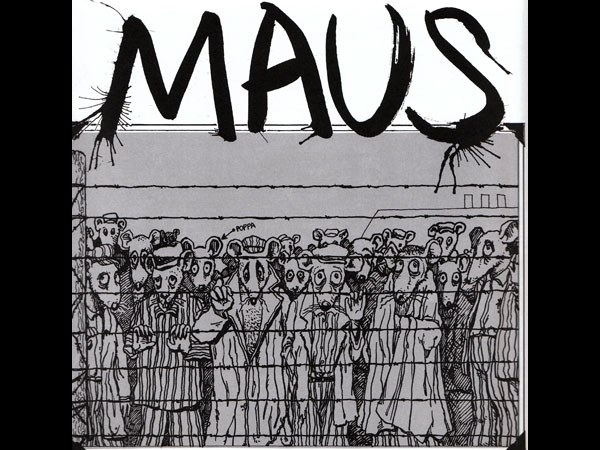

© 2008 by Art Spiegelman; reprinted with permission of the Wylie Agency, LLC."I resist becoming the Elie Wiesel of the comic book," Art Spiegelman once said. Too bad! Just as the name Wiesel will be forever linked with Night and other Holocaust literature, so the name Spiegelman will be forever suffixed with "You know, that guy who drew the comic book about Auschwitz." It doesn't matter what else he does. He can draw a graphic memoir of 9/11 starring the Katzenjammer Kids (In the Shadow of No Towers). He can write and publish charming kids' books (Jack and the Box and Open Me… I'm a Dog!). He can crucify the Easter Bunny on the cover of The New Yorker. It just doesn't matter.

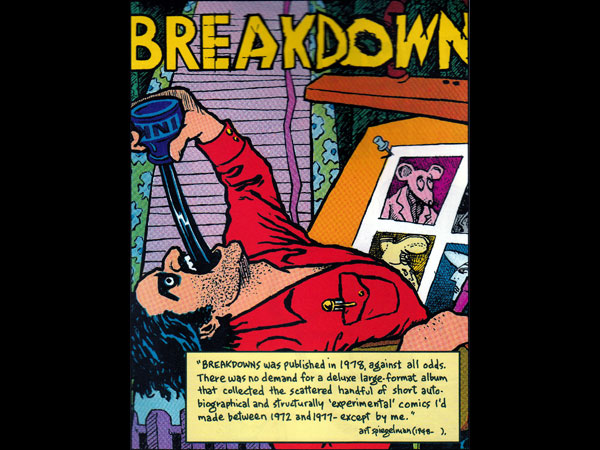

What was Spiegelman like before his epitaph was set? Breakdowns: Portrait of the Artist as a Young %@&*!, a reissue of a 1978 collection of Spiegelman's strips beginning in 1972 (including some pages from an early version of Maus), is a portrait of the artist as a young man scrambling for material.

-

CREDIT: © 2008 by Art Spiegelman; reprinted with permission of the Wylie Agency, LLC.

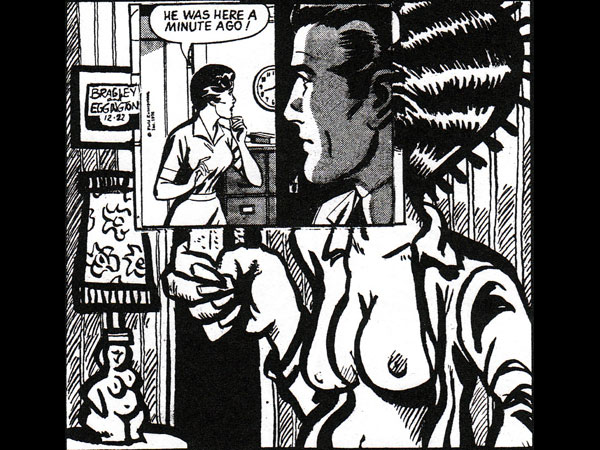

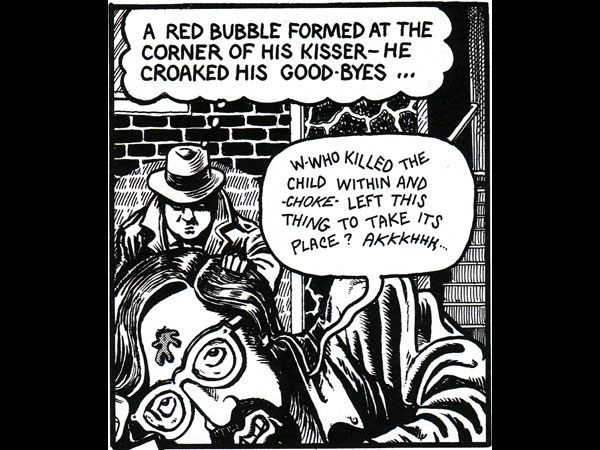

CREDIT: © 2008 by Art Spiegelman; reprinted with permission of the Wylie Agency, LLC.Everything in Breakdowns—the style, the tone, the narration, and the content—is unsettled and uncertain. There is blood. There is porn. There is pastiche. There is fiction. There is fact. There is low art chasing after high. There is Rex Morgan's head mixing it up with assorted comic bottoms, and a Bambi-esque deer perilously close to Picasso's bulls. The only constant is the figure of Spiegelman—depressed, mustachioed, and tormented in turn by the ghosts of Freud, Goya, Kafka, Picasso, Lewis Carroll, Henny Youngman, Little Nemo, Dick Tracy, and his own mother. In this uncombed mess of artistic ambition you can see strands of Spiegelman's grand story sticking out awkwardly.

For instance, in 1973 Spiegelman drew a Rube Goldberg-like cartoon called "Auto-Destructo: Suicide Device," involving a cat, a mouse, a man, and a copy of Munch's "The Scream." The suicide machine is set in motion when the man realizes the futility of the device he's part of and so the futility of all existence ("Oy Veh!" he cries).

-

© 2008 by Art Spiegelman; reprinted with permission of the Wylie Agency, LLC.

© 2008 by Art Spiegelman; reprinted with permission of the Wylie Agency, LLC.Or consider "Ace Hole, Midget Detective" (1974), a sendup of a hard-boiled detective comic. Here Floogleman, a Spiegelman stand-in, is shot and, with his last breath, gasps, "W-Who killed the child within … ?" Ace Hole jumps on the case. He chases down a dame modeled after one of Picasso's Dora Maar portraits and finds that she has shacked up with Mr. Potato Head and that together these in loco parental figures have decided to frame him for the murder of Floogleman (aka, the child within). Ace Hole wakes up in an ocean of tears and observes: "Reality wasn't a very nice place to visit, but there was nowhere else to go!"

And so Spiegelman went.

-

© 2008 by Art Spiegelman; reprinted with permission of the Wylie Agency, LLC.

© 2008 by Art Spiegelman; reprinted with permission of the Wylie Agency, LLC.It was around 1971 when he started to hit on his key material, his father's story in Auschwitz, as he notes in the introduction to Breakdowns. (Spiegelman's comic-strip introduction and his afterword are both new for this edition.) But the pieces took years to come together. He got the idea of using cats and mice when his film teacher, Ken Jacobs, pointed out that Mickey Mouse is "just Al Jolson with big ears," a racist caricature. (Jacobs also told him to think of "paintings as giant comics panels.") After a brief and fruitless attempt to make a cat-and-mouse comic about race relations in America ("Ku Klux Kats!" he thinks to himself), Spiegelman dove into his own family history. He interviewed his father, Vladek, on tape and began drawing his Holocaust story with rodents. And the rest, as they say, is history—or at least half a history.

-

© 2008 by Art Spiegelman; reprinted with permission of the Wylie Agency, LLC.

© 2008 by Art Spiegelman; reprinted with permission of the Wylie Agency, LLC.The other half—the mother half, told in a journal that Spiegelman's mother wrote, hoping her son would eventually read it—never saw the light of day. Spiegelman's father burned it without reading it. (See Maus, Vol. 1.)

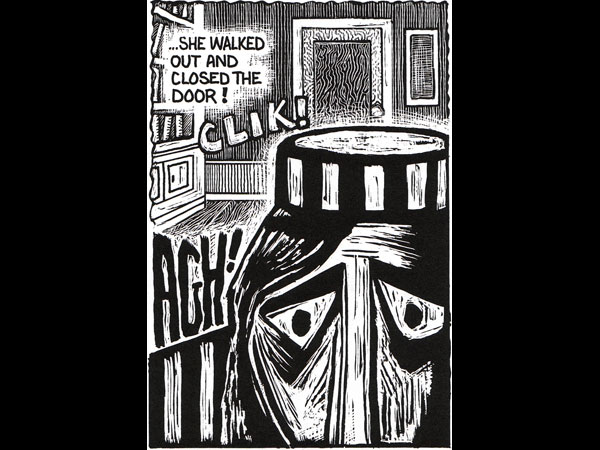

One surprise in Breakdowns is the amount of space and energy that Spiegelman devotes to his mother, Anja, in the introduction. Before this, the reader's main impression of her came from Spiegelman's bleak, four-page, expressionist-style relief-print strip that is buried in Maus, "Prisoner on the Hell Planet," which tells how Anja committed "the perfect crime," her suicide in 1968. ("You murdered me, mommy, and you left me here to take the rap!!!")

-

© 2008 by Art Spiegelman; reprinted with permission of the Wylie Agency, LLC.

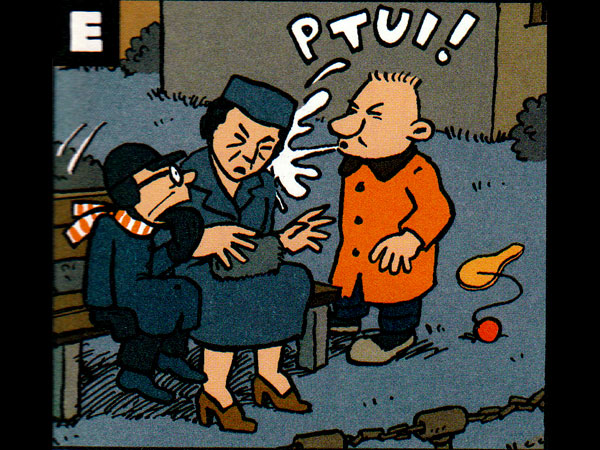

© 2008 by Art Spiegelman; reprinted with permission of the Wylie Agency, LLC.Although "Prisoner on the Hell Planet" appears in Breakdowns, too, Spiegelman also points to happier times with his mom. In the introduction to the book, drawn in a sweet Peanuts-y style, he demonstrates how he and his mother laughed at The Dick Van Dyke Show together and played the squiggle game together, completing each other's drawings. (His mother always drew a hairdo on the same old face.) Indeed, she had a lot to do with his early life in comics. She bought him his first copy of MAD magazine ("Just don't tell daddy I spent my grocery money on it!") and gave him his first Freudian-edged taste of being totally powerless in the world (an essential part of any cartoonist's life), by sitting timidly as a bully spat on her.

-

© 2008 by Art Spiegelman; reprinted with permission of the Wylie Agency, LLC.

© 2008 by Art Spiegelman; reprinted with permission of the Wylie Agency, LLC.Ah, youth! It's a shock to learn, in the afterword to Breakdowns, that Spiegelman now looks back at his harrowing past with a touch of nostalgia: "I envy the wild-eyed, ink-swilling young artist who made the strips gathered in Breakdowns thirty years ago. … I admire his ambition, his enthusiasm, his single-mindedness and his skinniness. He was on fire, alienated and ignored, but arrogantly certain that his book would be a central artifact in the history of Modernism." Envy? Really?

Spiegelman's envy of his pre-Maus self only makes sense if you consider what it must be like to be Spiegelman post-Maus. The tremendous success of that book must have planted in him a new kind of survivor guilt—the guilt that comes from realizing that without your family tragedy you might never have had a story to tell. Thanks for the plot, Mom and Dad. Sorry for your trouble. It's the kind of guilt you can imagine other great graphic memoirists—including Alison Bechdel (Fun Home), Marjane Satrapi (Persepolis), and David B. (Epileptic)—having, too. This list, by the way, suggests how wrongheaded the term graphic novel is, since many great "graphic novels" turn out to be in some sense graphic memoirs.

-

© 2008 by Art Spiegelman; reprinted with permission of the Wylie Agency, LLC.

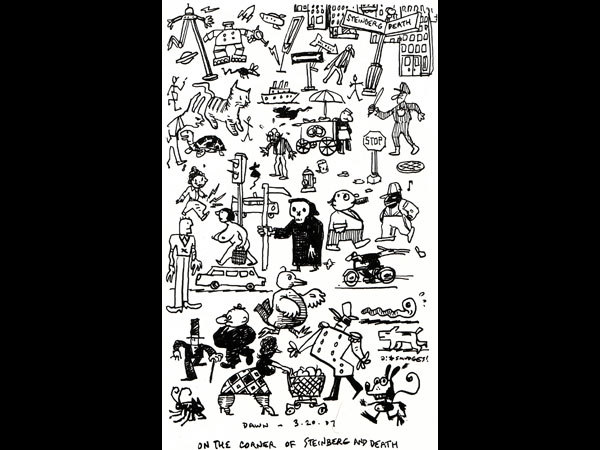

© 2008 by Art Spiegelman; reprinted with permission of the Wylie Agency, LLC.If Spiegelman's Breakdowns is a portrait of the artist before he has realized his key material, then Autophobia, Spiegelman's contribution to McSweeney's Issue 27 (2008), is a portrait of the artist after he has finished with that material. Autophobia, a sketchbook that Spiegelman kept in the spring of 2007, when he was finishing the introduction to Breakdowns, is about the impossibility of drawing without inhibition after Mauschwitz. Think about it: If the Holocaust is your opera, then what will be your encore? Here, the ghosts haunting Spiegelman are no longer Freud and Henny Youngman so much as R. Crumb and Saul Steinberg—those fertile doodlers who never stopped drawing for lack of a grand story.

-

© 2008 by Art Spiegelman; reprinted with permission of the Wylie Agency, LLC.

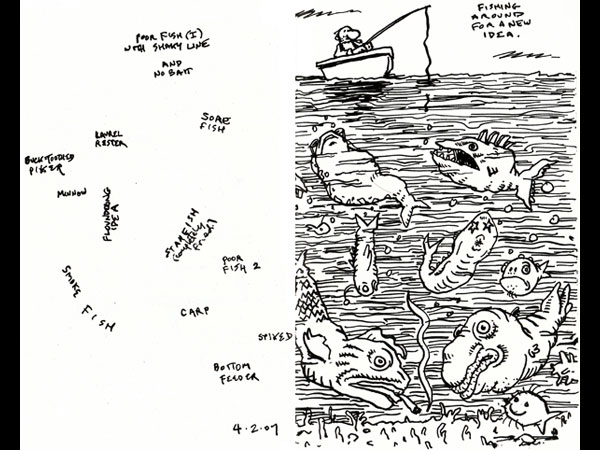

© 2008 by Art Spiegelman; reprinted with permission of the Wylie Agency, LLC.In a style that's looser and more fetching than any that he's used since Maus, Spiegelman displays his anxiety about drawing. His scrappy line, trying to be casual and doodley, is worried, wondering about his place in art. He draws himself as an aerialist walking the line between Crumb (Mr. Natural) and Steinberg (Mr. Concept). He refers to himself as a "nudnik descending a staircase," as a "megalomaniac with an inferiority complex," as a man "fishing around for a new idea" in toxic waters, and as a carp. (Yes, fish seem to have replaced mice as the vermin of choice.) He worries about the paper he draws on. It's too thick. It's too thin. When he makes a mistake—writing "shit in the bottle," rather than "ship in the bottle"—he cannot stop thinking about it. He cannot stop thinking about himself. (His name, appropriately, means "mirrorman.") He wonders whether by making enough drafting mistakes he can find a style.

-

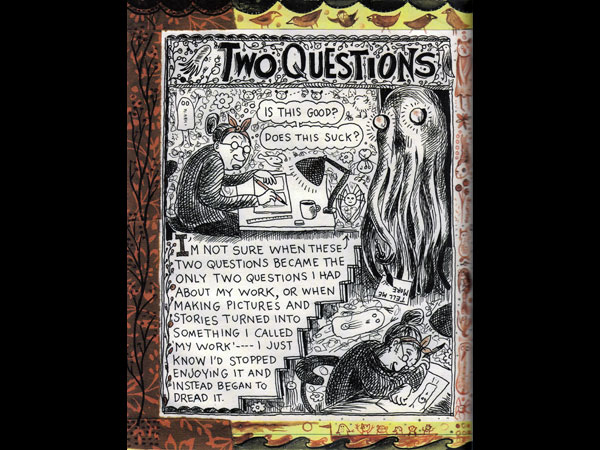

© Lynda Barry.

© Lynda Barry.Spiegelman is tortured by the two dreaded questions that Lynda Barry poses in What It Is, her new book on drawing inhibition: "Is this good?" and "Does this suck?" She has methods for overcoming these demons, and they have to do with—surprise!—turning your memories, even the most mundane ones, into images. Spiegelman, like her, wants to cast his line with the wild ones. But can he? Or is he too self-conscious, too self-critical?

-

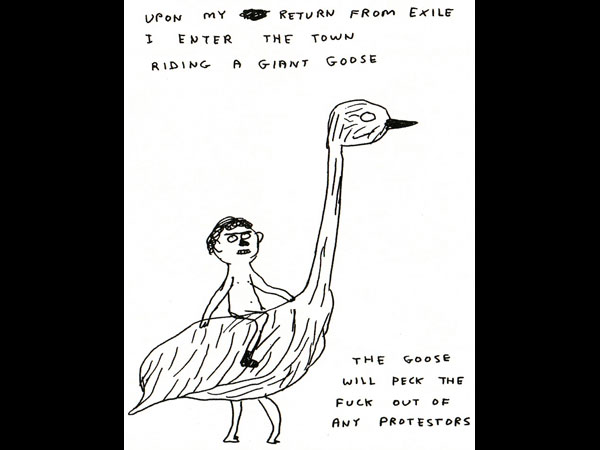

© David Shrigley.

© David Shrigley.Conveniently cased in the same McSweeney's box with Autophobia is a slim volume called Lots of Things Like This, which serves as a catalog of the sort of graphic artist that Spiegelman is not. This book of plotless imperfectionists includes Raymond Pettibon, David Shrigley, William Steig, Maira Kalman, Jean-Michel Basquiat, and Kenneth Koch. Like Spiegelman, they all use words and pictures, but unlike him they have no story, no history weighing them down. Hey, they're just playing.

Their handwriting is often awful, and some even use an ungodly mix of cursive and Roman letters. Words for them are funny objects with nothing better to do than comment on a picture or deface it, as Dave Eggers, McSweeney's editor, notes. When these artists "screw up a word," which they do quite a lot, "instead of starting over, they just cross the word out and write it again." And when their lines decide to take them for a little walk, they don't fret about what kind of hideous dump they're going to end up in. If you look carefully, you can almost see Spiegelman muttering after them, "Ace Holes!"