Reinventing a D.C. Theater

-

Photograph by Balthazar Korab, courtesy Bing Thom Architects.

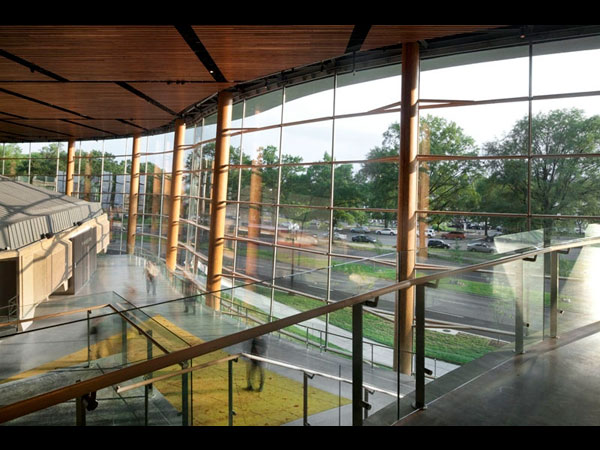

Photograph by Balthazar Korab, courtesy Bing Thom Architects.I first saw the Arena Stage in Washington, D.C., when I was on a scholarship study tour with several other architecture students from across Canada. It was 1964, and the theater, designed by Chicago architect Harry Weese, was one of the capital's few Modernist buildings. One of my tour companions was Bing Thom from Vancouver, and I remember standing outside the building heatedly discussing the all-too-evident failure of 1960s-style urban renewal, the devastating effects of which were visible in the surrounding neighborhood. Now Thom has returned to Washington to design a major expansion to the Arena Stage. His solution is unexpected. Like Richard Rogers (featured in Part 1), Thom is an uncompromising Modernist. Weese admirers—a monograph revisiting the architect's work has appeared recently—will no doubt complain, for the new building quite literally envelopes the old.

-

Photograph by Nic Lehoux, courtesy Bing Thom Architects.

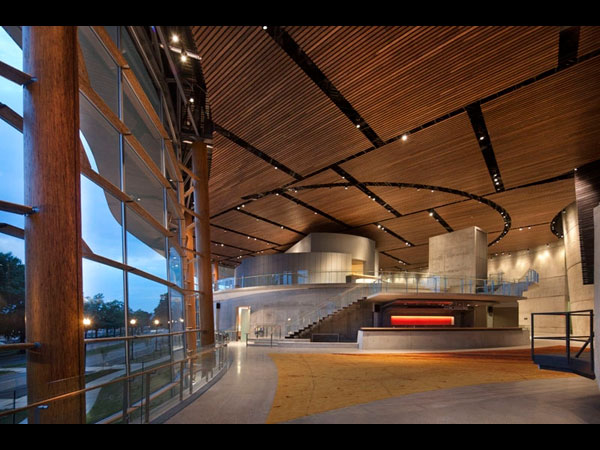

Photograph by Nic Lehoux, courtesy Bing Thom Architects.Thom has completely encased the original theater in a hangarlike glazed lobby. Weese's octagonal brick and concrete building—the first purpose-designed theater-in-the-round in the United States—is visible on the left side of the slide, sitting there like a preserved archaeological artifact. Thom's architectural strategy could be taken for impertinence, except that the glass enclosure is almost casually draped over the building, allowing it to maintain its dignity. The new architecture veers from the old; indeed, it veers from Washington orthodoxy, for instead of marble and granite, there is—surprise!—a lot of wood.

-

Photograph by Nic Lehoux, courtesy Bing Thom Architects.

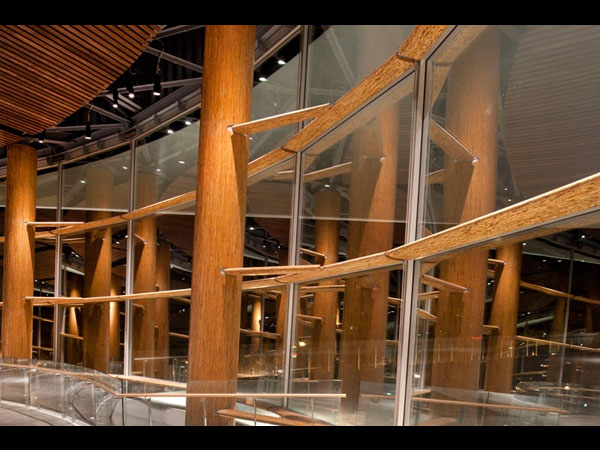

Photograph by Nic Lehoux, courtesy Bing Thom Architects.The 50-foot-tall timber columns and structural braces are made of an engineered wood product manufactured out of wood strands bonded together with adhesive. Stronger than sawn wood, Parallam has a pleasant organic appearance and can be made in any length and in different shapes. The elliptical cross-section used here makes the columns resemble yacht masts, and the pronounced stainless-steel details recall Rogers's high-tech style, but the effect is warm and woodsy rather than cool and machinelike. Technological innovation is a hallmark of Bing Thom Architects, which Thom founded in 1980 after apprenticing with the great Canadian architect Arthur Erickson. Thom has designed a number of acclaimed buildings in Canada, including the University of British Columbia's Chan Centre for the Performing Arts, which led directly to the Arena Stage commission.

-

Photograph by Nic Lehoux, courtesy Bing Thom Architects.

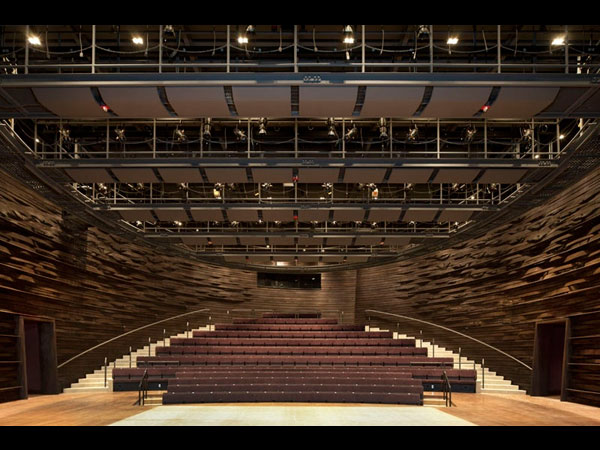

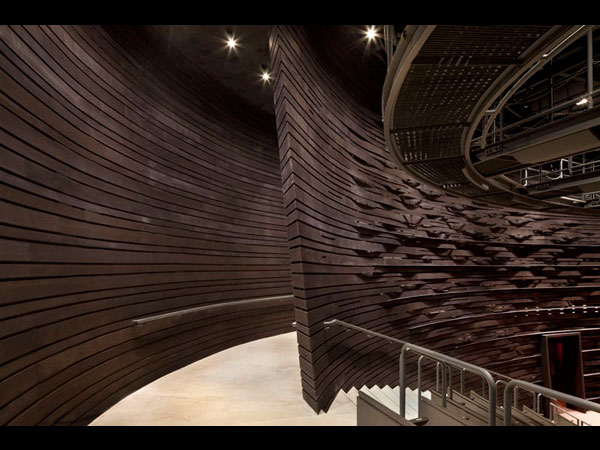

Photograph by Nic Lehoux, courtesy Bing Thom Architects.The other prominent use of wood in Arena Stage is in a new performance space, a 200-seat theater where artistic director Molly Smith will stage experimental plays. Such venues are often called "black boxes," because they are usually neutral, black-painted studios with movable lights, flexible seating, and adaptable stages. Yet Thom came to the conclusion that the theater should have its own identifiable character, and instead of a box, he created an oval enclosure that he christened the "Cradle"—a place where new plays would be brought to life.

-

Photograph by Nic Lehoux, courtesy Bing Thom Architects.

Photograph by Nic Lehoux, courtesy Bing Thom Architects.The little theater sits inside an exposed concrete drum that acts as a noise barrier (and also serves as the central support for the roof). The problem is that an oval shape creates acoustic problems for the audience and the performers. Thom and his partner Michael Heeney devised a second, inner drum consisting of an open weave of wood slats that dampens the sound without creating disturbing echoes. The space between the drums houses a ramped passage that leads, somewhat mysteriously, up into the theater. Instead of a black box, a black basket.

-

Photograph by Nic Lehoux, courtesy Bing Thom Architects.

Photograph by Nic Lehoux, courtesy Bing Thom Architects.This is not the first expansion of the Arena Stage. In 1971, Weese added a 500-seat theater with a modified thrust stage, suitable for classic plays and small-scale musicals. The current expansion preserves the interior of this performance space, but wraps the banal exterior in concrete and places a restaurant on the roof (right). The lobby of the new Arena Stage is a Richard Serra-like landscape, with the floor meandering and climbing between the curved walls.

-

Photograph by Nic Lehoux, courtesy Bing Thom Architects.

Photograph by Nic Lehoux, courtesy Bing Thom Architects.The restaurant opens onto a roof terrace that takes advantage of Washington's mild climate. There are views down to the Washington Channel and East Potomac Park, but the most striking sight is the distant Washington Monument. The roof terrace is the kind of "extra" space that makes this building such a successful gathering place. Dramatic glazed theater lobbies are a cliché of modern architecture, but this one works because of the variety of its spaces and its resistance to gratuitous monumentality.

-

Photograph by Nic Lehoux, courtesy Bing Thom Architects.

Photograph by Nic Lehoux, courtesy Bing Thom Architects.The major exterior architectural element is a 475-foot-long roof that covers the lobby and three theaters, and cantilevers out over the outdoor terrace. The curving roof is white with a razor-thin edge. While the complex composition of new and old plays out beneath, the roof acts as a unifying element, and also provides the memorable "wow" factor that is required of major cultural buildings today. Thom's talent is that unlike many architects, he does not allow the big gesture to compromise the many small gestures that make this complicated building a functional as well as an aesthetic success. Nor is this a fashionable blob building—the curve of the roof, while undoubtedly engineered using a computer, feels drawn by hand.

-

Photograph by Nic Lehoux, courtesy Bing Thom Architects.

Photograph by Nic Lehoux, courtesy Bing Thom Architects.The new Arena Stage may be the most un-Washingtonian building since Douglas Cardinal, another Canadian, designed the National Museum of the American Indian. The problem with Cardinal's curvaceous building is that it wants to be on the prairie or a mesa, and instead it sits on the National Mall; in short, it is out of place. Washington's neoclassical setting has often confounded modern architects; look at Gyo Obata's heavy-handed Air and Space Museum, Gordon Bunshaft's ponderous Hirshhorn Museum, Arthur Erickson's fussy Canadian Embassy. The site of the Arena Stage is some distance from the monumental core, and Thom has taken full advantage of this freedom, producing an audacious building that breathes fresh air into the nation's capital.