Augustus Saint-Gaudens

-

Sherman Monument in Grand Army Plaza, Augustus Saint-Gaudens, 1892-1903. Photograph by Jim Henderson. This image is in the public domain.

Sherman Monument in Grand Army Plaza, Augustus Saint-Gaudens, 1892-1903. Photograph by Jim Henderson. This image is in the public domain.The Augustus Saint-Gaudens show at the Metropolitan Museum in New York City is modest in scale, and a good way to enlarge the experience is to walk down Fifth Avenue to Grand Army Plaza and the Sherman Monument. The stirring figures atop a handsome granite pedestal designed by architect Charles Follen McKim are one of Saint-Gaudens' great works. The mounted Civil War general is depicted bareheaded with the wind lifting his cloak, preceded by the goddess Victory holding the palm branch of peace. Saint-Gaudens, notoriously slow, had taken 18 sittings to make a bust of Sherman; the model for Victory was Hettie Anderson, a popular African-American model. He sculpted Victory unclothed, then spent two weeks arranging her drapery. The monument is a reminder of how different Saint-Gaudens was from contemporary artists such as Claes Oldenburg, Richard Serra, and Jeff Koons, who make public sculptures but whose art is essentially private in nature. The Saint, as he was sometimes called, was an artist who derived his inspiration from the subjects of his public commissions.

-

CREDIT: Augustus Saint-Gaudens, Kenyon Cox, 1887. Oil on canvas. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Gift of friends of the artist, through August F. Jaccaci.

CREDIT: Augustus Saint-Gaudens, Kenyon Cox, 1887. Oil on canvas. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Gift of friends of the artist, through August F. Jaccaci.Saint-Gaudens was born in Dublin in 1848 to a French father and an Irish mother. The family immigrated to America when he was an infant and settled in New York City. At 13, he was apprenticed as a cameo cutter. Cameos are tiny images—often portraits—cut into shell or stone, and after six years, he developed an extraordinary skill in shallow-relief carving. He studied art in Paris and Rome, developed a love of the Italian Renaissance, and later divided his time among New York, Paris, and a rural retreat in Cornish, N.H. His friend Kenyon Cox painted him in 1887 in his 36th Street studio, intently modeling a bas-relief portrait of the painter William Merritt Chase. The portrait was to be a birthday present from Saint-Gaudens, who had a wide circle of friends, including many architects: H.H. Richardson, Daniel Burnham, Stanford White, and his partner McKim. These friendships, which were the source of commissions and regular collaborations, represent a creative camaraderie among artists and architects that is rare today.

-

CREDIT: The Children of Jacob H. Schiff, Augustus Saint-Gaudens, 1884-85. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Gift of Jacob H. Schiff.

CREDIT: The Children of Jacob H. Schiff, Augustus Saint-Gaudens, 1884-85. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Gift of Jacob H. Schiff.Saint-Gaudens, a master of alto- and bas-relief, made portraits of his friends—John Singer Sargent, Francis D. Millet, art critic Mariana Van Rensselaer—as well of the rich and famous: Cornelius Vanderbilt, Mrs. Grover Cleveland, Robert Louis Stevenson. Many of these reliefs have an endearing, sketchy quality. This large (about 4-by-5-foot) plaque depicting Mortimer and Frieda Schiff was a gift to their father, a New York banker, from a British friend. Unlike paintings or photographs, bas-reliefs appear three-dimensional yet are often less than an inch deep, an illusion that gives them a sort of magical authority. Note how the rounded toe of Mortimer's right foot protrudes over the frame, as if he were about to step out. The sculptor did many clay studies of the children, finally adding his own Scottish deerhound, Dunrobin, to complete the composition. The original plaque is bronze; Schiff had this marble copy made and gave it to the Metropolitan Museum.

-

Adams Memorial in Rock Creek Cemetery,CREDIT: Augustus Saint-Gaudens, 1891. This image is licensed under GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.2.

Adams Memorial in Rock Creek Cemetery,CREDIT: Augustus Saint-Gaudens, 1891. This image is licensed under GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.2.Saint Gaudens sculpted several cemetery memorials. In 1886, he was approached by the eminent historian Henry Adams with a seemingly impossible commission: a grave monument for his wife, Marian, who had taken her own life the year before. At Adams' suggestion, Saint-Gaudens studied Buddhist monuments as well as Michelangelo's sibyls in the Sistine Chapel and produced this haunting work. The bronze figure is in Washington, D.C.'s Rock Creek Cemetery; the setting was designed by Stanford White.

-

CREDIT: Amor Caritas, Augustus Saint-Gaudens, 1880-98. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund.

CREDIT: Amor Caritas, Augustus Saint-Gaudens, 1880-98. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund.The figure of Victory in the Sherman Monument is a version of the idealized classical female that appears in many Saint-Gaudens works: a pair of caryatids supporting a massive mantel in a fireplace that he designed for the entrance hall of Cornelius Vanderbilt's house (now displayed in the Met) and several tombs and cemetery monuments. Here she takes the form of an angel, wearing a flowing chiton and a garland on her head, and holding a tablet. Amor Caritas (Love Charity) was not a commissioned work, although 40-inch-high bronze reductions enjoyed considerable commercial success, and the Musée du Luxembourg in Paris purchased a full-size casting—a rare honor for an American artist.

-

CREDIT: Diana, Augustus Saint-Gaudens, 1892-93. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund.

CREDIT: Diana, Augustus Saint-Gaudens, 1892-93. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund.Perhaps Saint-Gaudens most popular work is the figure of Diana, the Roman goddess of the hunt. Saint-Gaudens made it to serve as a finial for the top of the tower of Madison Square Garden, recently designed by his close friend Stanford White. The racy idea of placing a nude on top of a 32-story tower (the second tallest structure in the city) probably came from White, a noted womanizer. It must have appealed to Saint-Gaudens, too, for he charged only for his expenses and based the statue on Davida Clark, his model and mistress. Saint-Gaudens and White deemed the first 18-foot riveted-copper figure too large and replaced it with a 13-foot version (now in the Philadelphia Museum of Art). The small bronze casting shown here is one of several that Saint-Gaudens made later for sale to collectors.

-

Farragut Memorial in Madison Square ParkCREDIT: , Augustus Saint-Gaudens, 1881. This image is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 2.5 License.

Farragut Memorial in Madison Square ParkCREDIT: , Augustus Saint-Gaudens, 1881. This image is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 2.5 License.Saint-Gaudens first public monument was the Farragut Memorial in Madison Square Park in New York City. It is an extraordinary combination of tradition and innovation. The bronze figure is placed on a granite (originally bluestone) exedra, or bench. Farragut is in naval uniform, holding field glasses, and posed as if on the deck of a ship; the skirt of his coat blown back by a breeze. The allegorical figures on the pedestal, representing Courage and Loyalty, crouch among stylized waves; dolphins, another marine motif, form the ends of the bench. An inscription, in Saint-Gaudens' characteristic Roman-style lettering, celebrates the admiral's accomplishments. What is remarkable about the monument is its small size and great compression, a lesson for today's sprawling memorials, which seem intent on educating the visitor, often at great length. Saint-Gaudens and Stanford White, who designed the base, tell a story, too, but it is more like a haiku.

-

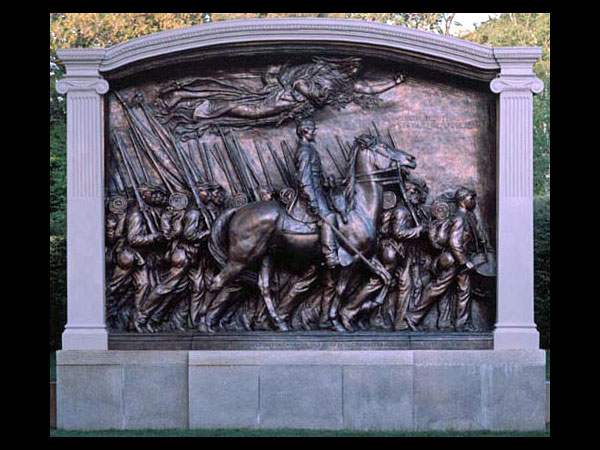

Robert Gould Shaw MemorialCREDIT: , Augustus Saint-Gaudens, 1897. This image is in the public domain.

Robert Gould Shaw MemorialCREDIT: , Augustus Saint-Gaudens, 1897. This image is in the public domain.The memorial to Col. Robert Gould Shaw and the volunteer soldiers of the African-American 54th Massachusetts Regiment stands at the edge of Boston Common. The marching soldiers (16 are visible), preceded by a drummer boy, are rendered in high relief and form a background to the freestanding equestrian portrait of Shaw. The setting, designed by McKim, contains lines from a poem by James Russell Lowell. As he did so often, Saint-Gaudens wove together intense realism with spiritual allegory, the latter in the form of a floating female figure holding laurel leaves, symbolizing glory, and poppies, symbolizing death—half the regiment as well as Gould died in a fateful attack on Fort Wagner in Charleston, S.C.* This is generally considered Saint-Gaudens' great achievement, and it represents a pinnacle of modern American public sculpture, rarely—if ever—surpassed.

*Correction, Nov. 5, 2009: Due to a copy-editing error, this slide originally referenced "Charleston, N.C.," instead of Charleston, S.C.

-

Double Eagle coin,CREDIT: Augustus Saint-Gaudens, 1933. This image is in the public domain.

Double Eagle coin,CREDIT: Augustus Saint-Gaudens, 1933. This image is in the public domain.In 1905, President Theodore Roosevelt, dissatisfied with the coins being issued by the U.S. Mint, prevailed on an ailing Saint-Gaudens (he had cancer and would die two years later, only 59), to design 1-cent, $10, and $20 coins. The 1-cent was never minted, but the $20 gold piece—a double eagle—is widely considered the most beautiful American coin ever made. (It circulated until 1933, when the United States went off the gold standard.)* The obverse shows a dynamic Liberty (Hettie Anderson, again) holding a torch and palm leaf, the sun rays behind her symbolizing enlightenment. The reverse shows a soaring bald eagle with similar rays. Unlike the U.S. Mint today, which has issued such uninspired coins as the distinctly pedestrian state quarters—they appear to have been designed by committees—Saint-Gaudens understood that a coin could be a miniature sculpture. A work of public art in your pocket.

*Correction, Nov. 6, 2009: This slide originally stated that the $20 gold piece was struck but never circulated. In fact, it circulated until 1933.